“If you don’t go away you can’t come back”: Rediscovering the writing of Alan Sharp

“If you don’t go away you can’t come back”: Rediscovering the writing of Alan Sharp.

The Anti-hero’s Journey, The Work and Life of Alan Sharp, David Manderson, Peter Lang. Reviewed by Eleanor Thom

During the Covid lockdown I attended an online writing group. If I am honest, this was more social catch-up than work. David Manderson, previously a regular in the group, was absent because he was too busy actually writing. His book, The Anti-hero’s Journey, The Work and Life of Alan Sharp, was published last month by Peter Lang. We all knew David, but no one in the group was familiar with the writer, Alan Sharp. I had never heard of him before.

If he’d been in our meetings, David wouldn’t have been surprised at our blank faces. Later, he told me this is exactly what attracted him to the project. Manderson is a researcher and writer from Glasgow. He’s the author of short stories and a novel, Lost Bodies. The work of Scottish writer Alan Sharp is ripe for rediscovery. Scotland has swept Sharp under the rug, Manderson says, and this is a forgetting that needed to be understood and undone.

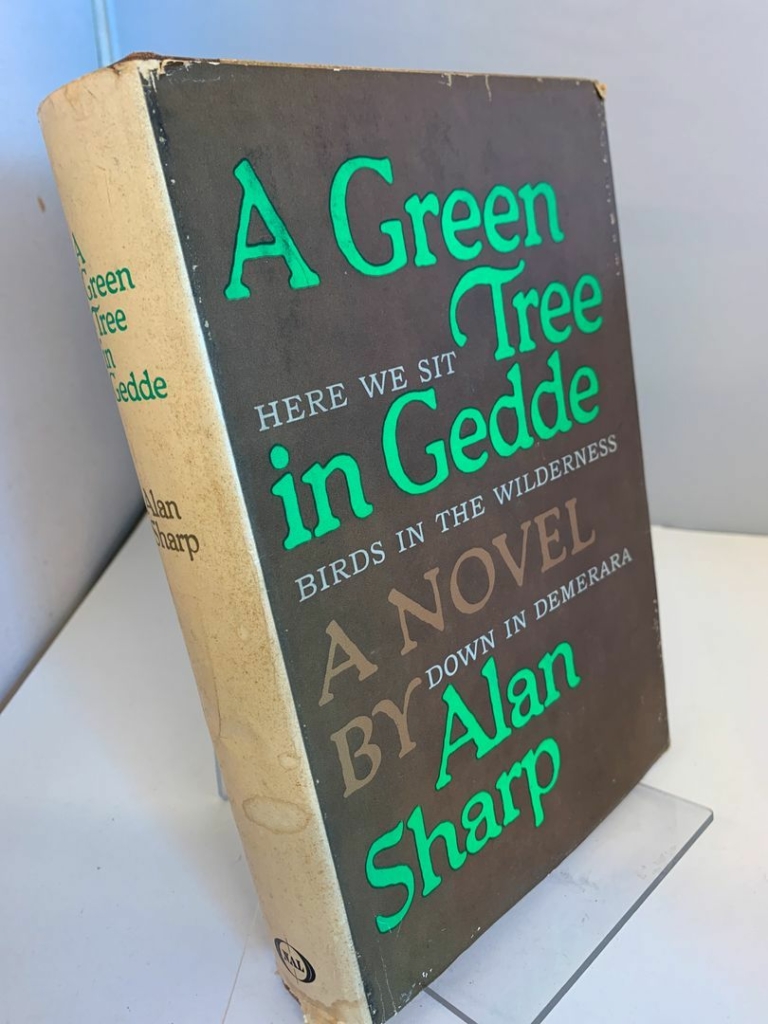

Looking back, I agree this is a surprising cultural blind spot. Many of our writing group were graduates of Glasgow University’s Creative Writing Masters, and Alan Sharp was a prolific and successful novelist and screenwriter from Scotland’s West Coast. Sharp’s debut novel A Green Tree in Gedde, had won the Scottish Arts Council Prize in 1967, beating writers including William McIlvanney and George MacKay Brown.

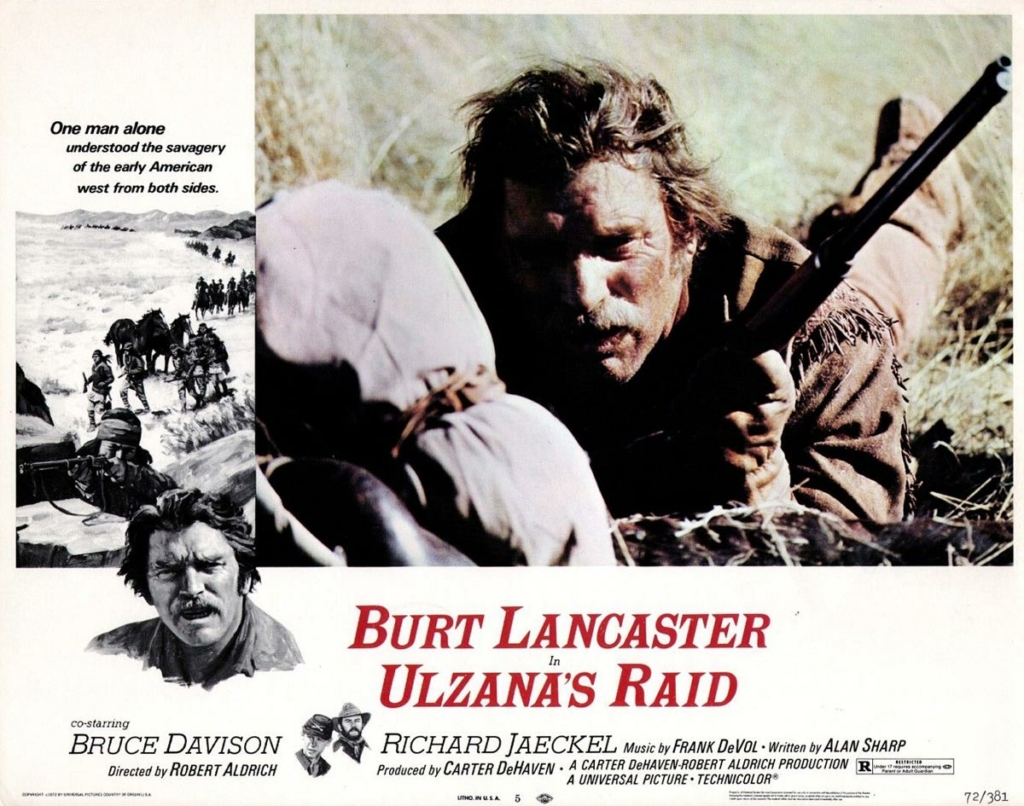

Sharp authored dozens of radio and television plays while living in London, and after relocating again to California he had five films made in Hollywood over five years, pushing the conventional narratives of the Western, a genre he had grown up watching, and the film noir. Many more films and telefilms followed, including the script he is best known for, Rob Roy. Working across multiple genres, his work has probably been enjoyed by more people worldwide than any other Scottish writer.

How was it possible that Alan Sharp’s name had passed every one of us writers by? As the adopted son of a Greenock shipyard worker, Sharp had been one of the first to defy literary convention in favour of creativity, employing the words that rolled off his tongue as a boy. He was certainly the first to take it to the big screen. It is a freedom which writers in Scotland now take for granted. “Scottishness was important to him,” Manderson writes. Born in 1934 in Alyth and raised in Greenock, Sharp’s success came after he left Scotland, but he eventually returned, splitting his time between Scotland, New Zealand and the USA.

The events in Alan Sharp’s life are very much a story, but Manderson puts Sharp’s writing centre stage. Biographical detail nevertheless emerges, in part because Sharp’s characters and settings so often reflected his personal experience. Manderson consulted Sharp’s large family and descendants, many of whom have had interesting lives themselves and are as widely dispersed as Sharp’s career. They were enthusiastic to help.

The focus of Manderson’s research was the Alan Sharp Papers Collection, established at Dundee University in 2013, the year Sharp died. The holdings include manuscripts, letters, notes, interview transcripts, reviews and audience reports, and Manderson examined this material meticulously. For the first time, he has made the progression of Sharp’s writing career across multiple genres visible in a single piece of research. Manderson identifies themes, characters and motifs that followed Sharp even as he moved around the world adapting to other cultures and establishing himself as a writer for different audiences.

“If you don’t go away you can’t come back,” writes Sharp in A Green Tree in Gedde. Manderson begins his first chapter with this quote, one which is key to the reading of Sharp’s own life, and so many of the narratives he created. His typical main characters are men who suffer from inner insecurities, a longing for life to be different. They go on quests for new vistas both external and internal, but whether they physically travel away or remain where they are, what they strive for is out of reach. Sharp’s stories can seem fatalistic, a characteristic that has been regarded as a stamp of Scottishness.

Sharp himself left Greenock behind him and headed for London in the mid-sixties. It was an era when large numbers of young people left Scotland for the South. Sharp lived in Primrose Hill, round the corner from a spot on the Grand Union Canal where my parents lived on a boat.

They were part of that same exodus from Scotland, from Elgin in their case, and reading about Sharp’s time in London I couldn’t help but sense some cultural overlap. My mother and father were adopted by a group of artists and actors. It was a close-knit circle, and a decade later they all had young families, children I mixed with as if we were cousins. I remember how dumbfounded we were as teenagers, learning that our parents were not all in their original couples. Two of our mothers had been dating the ‘wrong’ dads in the sixties, but they all stayed friends. We knew we would never be as cool as our hippy parents.

Sharp was regarded in Scotland as belonging to the ‘free-love’ movement, and this affected his reputation. Imagining provincial life back in Greenock, Alan Sharp wrote in his first novel of inertia so stifling it caused even the blood to stiffen on trays in butchers’ windows. I can easily imagine my mother’s wry agreement with this sentiment. Sharp’s prizewinning novel was for a time banned by Edinburgh libraries for the sexual taboos it depicted, but this only boosted its popularity. A Green Tree in Gedde was successful in the way it captured a moment, the massive societal change that was already in the making. It became a bestseller.

Being a writer in exile brings advantages and disadvantages. Within Scotland, some believed that to leave home for London was to sell out. It was an accusation levelled not just at Sharp, but also at Muriel Spark and others. Sharp’s second novel was less successful, and at this point, he pivoted for the first time. Over twenty scripts for radio and television followed, but it wasn’t long before Scotland regarded him as a ‘lost’ and ‘once promising’ author. Writing for radio and screen was not yet regarded on the literary scene as an equally worthy outlet.

Accusations of homophobia and misogyny further undermined Sharp’s reputation at home. His texts were no longer kept in print and were removed from course syllabuses. David Manderson is keen to address this, believing that accusations of homophobia and misogyny were unfounded. On the contrary, he says, Sharp’s work was more about deconstructing the male hero in Hollywood and his writing was not extolling but exploring common beliefs about gender and sexuality.

Complex, strong female characters do appear multiple times throughout Sharp’s career, on screen, on radio and in print, and they possess inner qualities that the male anti-heroes fundamentally lack. In many cases, they are still trapped by circumstance, but Manderson reminds readers that Sharp was a realist. He wrote about life in societies where women’s opportunities were curtailed.

David Manderson would like to see Alan Sharp introduced to a new generation of Scottish literature and film students. His early work from London provides, Manderson says, a glimpse into a fascinating period of modernist radio and drama, and Sharp remained a prolific writer till the end of his life. His writing has continued to be produced since his death. In 2019, a co-written screenplay Our Ladies was released to warm reviews, and Vain Glory is a series currently in development. Picture This, which Manderson would like to see published, is an experimental novel that merges screenplay and prose. It achieves something new, Manderson says.

For anyone wishing to look back at Sharp’s early work, the novels can only be found on the second-hand market, but I was able to access at least some of his film work via streaming services. Rob Roy (1995), Ulzana’s Raid (1972), Night Moves (1975), Billy Two Hats (1974) and The Last Run (1971) were all available.

And then there’s the tantalising story about Sharp’s missing third novel, believed to be called The Apple Pickers. This novel was spoken about as forthcoming for years, but it never appeared. The manuscript, if any of it still exists, has yet to be found. Manderson believes it may be in storage in New Zealand with other unseen material. When I met with him, I could sense his enthusiasm for finding this missing piece of the puzzle, and I hope he will soon get a chance to go in search of it.

Delighted to see this recognition of Alan Sharp’s importance. I lived in Greenock from birth until 1985 (was at school with playwright Bill Bryden and footballer Charlie Cooke) and loved “A Tree in Gedde” as well as the novels of Robin Jenkins.

By the way, you need to do something about catchpa – this is the third time I’ve had to activate it

He is an important figure, Ronald, and his work should not be forgotten. Thanks for your comment.

Thanks for this Ronald, I’m glad you liked this piece. You could always ask your local library to order it.

The guy who deserves credit for ‘rediscovering’ Alan Sharp is the film producer Peter Broughan, who called him up to write ROB ROY…

I know that for Peter he was always a very important figure…

I didn’t know his work – thanks to Eleanor for this piece of missing cultural history

Thanks to Eleanor from me too for this review, which is lovely. Lots of nice comments in from people I know who’ve seen it here,

Alan Sharp’s “Night Moves” was one of my favourite private eye movies of the seventies and one of my favourite Gene Hackman films ….but much as I admired his other work I didn’t know until today that he wrote it.

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0073453/

What about Gene Hackman in “Crimson Tide” eh?

Did you see that Tony Scott film?

I have discovered at a late age how much I like dumb action movies. They are so transparently ideological… They’re like a goldmine for the cultural critic (though I am not one).

As for “Rob Roy”, again, far too late, I discovered that it was a staple of the Scottish stage right through the 19th century.

It’s like the trauma of the Great War caused something like collective amnesia…

All these traditions were suddenly lost…

But the guy to talk to about Alan Sharp is Peter Broughan, who talks about him with real passion as a figure of working class Scotland, but also a great writer… (I haven’t read his novels)

Gene Hackman AND James Gandolfini in the same film (“Crimson Tide”)… It doesn’t get much better than that…

Denzil Washington as the sappy liberal Woke character who tries to stop the Hackman character nuking Russia…

Couldn’t be more contemporary…

Couldn’t be more relevant…

Who’s complaining?

He sure was a working class Scottish figure, Douglas. Keep your eyes peeled for the Alan Sharp season coming up at the GFT in September.

I’m really pleased you came across this article then, Stuart. Yes, ‘Night Moves’ is excellent, a masterpiece in my opinion. There’s also an excellent novelization.

Definitely by Alan Sharp and there’s a Corgi novelisation too, plus fascinating interviews with Sharp and Arthur Penn about the whole experience. The screenwriter and his director fell out in the end and I don’t think spoke again. But that’s what happens when your film is a flop. If you want some links etc., get in touch with me through my email address below.

He certainly did, Stuart. Small word, eh?

Thanks Bella!

Great to see stuff like this being brought to the fore.

Glad you like it, Alistair!

Does anyone have a contact number for Alan Sharp’s daughters, Louise and Nola? My Mum was friends with their Grandmother, Mrs Donachie, and their Mum, Margaret. Both have sadly passed away and my own Mum died this year. Going through old photos and slides of my Mum’s I have identified lots of Louise and Nola with their Mum and also of their dad, Alan which I would like to send on to them. The photos of Alan are in his teens or early 20s. Alan was friends with my dad, in Greenock shipyards where they worked together. If anyone reads this and can help, I would be grateful. All I know is that Louise lived in Los Angeles and cared for her dad when he died there. We holidayed in London with Margaret, Louise and Nola and Henry the giant brown poodle and Bridget the Midget, a lovely black and white cat and Nola’s hamster, whose name I can’t remember!

Elizabeth – Did anyone reply to your request for info on Louise and Nola?

Hi Viki I just replied to it. I’ll send her Louise’s number. Dave

Hi Elizabeth, I’ve just seen this message from you. I think I can get you Louise’s number. I talked to her on zoom or some other digital way, so I’ll dig out what I have and send you those details.

I’m sorry to say, however, that Nola sadly died a number of years ago. I don’t know the details but I heard she left two young sons. I’m sorry for your loss.

I’ll get Louise’s details and send them to you. Tomorrow some time. Hope thats okay.

David (I wrote the book reviewed here.)

Hello David, Nola and I were incredibly best friends since we were 8 years old. I miss her terribly since her death from lung cancer. Yes, she left behind twin sons whom her sister Louise, was looking after. Since Nola’s funeral I have lost contact with Louise and would love to be in touch again. I was very close to their mother, Margaret. I knew Alan very well. When he was in UK he would pick Nola up from school in a lemon E type Jag! It Really looking forward to reading your book. Alan was exceptionally gifted. Very witty. A lovely man. Took Nola and I to our first gig – Donovan !!! – at The Roundhouse!

Hi Elizabeth, I’m sorry I forgot to get back to you, Louise Sharp’s email of ouise sharp if you still want to get in touch.

Dave

Me again, Elizabeth. If you knew Nola’s grandmother, her Mum and Louise + Henry, Bridget the Midget and hamster – we must have met? In the mansion flat in Richmond? Xxx