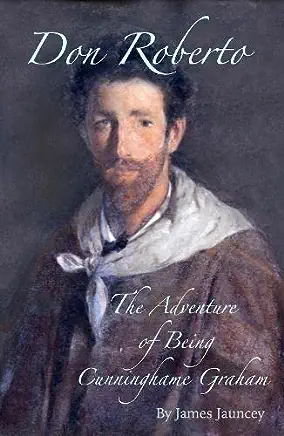

The Adventure of Being Cunninghame Graham

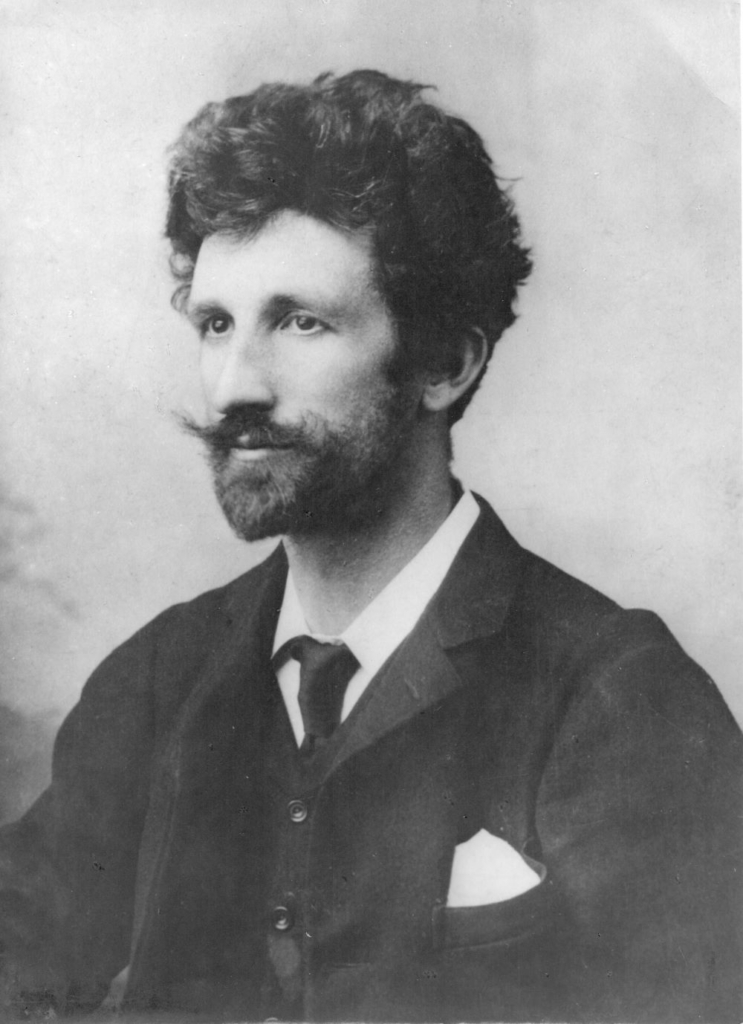

The first socialist MP: Robert Bontine Cunninghame Grahame

Don Roberto: The Adventure of Being Cunninghame Graham by Jamie Jauncey, Scotland Street Press, £24.99 hardback.

Reviewed by Charlie Lynch

The first declared socialist MP elected in Britain was a renegade Scottish aristocrat. Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham was later amongst the founders of the Scottish National Party. One of the most prominent and complex figures of late nineteenth and early twentieth century Scottish life, Cunninghame Graham could variously be described as a politician, a social reformer, a traveller, and adventurer as well as a writer and journalist. As his great-nephew, Jamie Jauncey, writes in this fascinating book, part biography and part family memoir, Cunninghame Graham was a man driven by sentiment.

He was a man of action who embodied a host of apparently contrary positions with ease. Deeply private and loathe to reveal his inner life in his copious writings, he was sociable and gregarious, and clearly enjoyed public attention. A progressive who deplored the effects of progress, Cunninghame Graham delighted in traditional ways of life. He was a privileged country landowner who became, with sincerity, a campaigning socialist whose views shocked the establishment and who counted amongst his friends William Morris and Keir Hardie. He was an anti-imperialist ultimately loyal to the British Empire, who desired greater autonomy for Scotland within the Union, and regarded Irish Republicanism with alarm and suspicion. He was a visionary nationalist, and at the same time, a cosmopolitan internationalist with links to Argentina and to Spain.

A review can only provide the most basic of introductions to the life of Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham. He was a man around whom legends accumulated, wholly encouraged by their subject, who knew that his reputation as a romantic man of adventure and letters helped shield him from scrutiny and obscure uncomfortable truths. Born in 1852, his early life was one of privilege tempered by insecurity and disturbance. His father had succumbed to mental illness, rushed at his mother with a sword and had been confined to seclusion for the rest of remainder of his life. With the family finances restricted and under the control of a lawyer, Robert set sail for South America as a teenager in 1870 with the intention of making a fortune in cattle ranching. He proved to be a poor businessman but an indefatigable horseman and adventurer who rode with gauchos and who may have narrowly escaped conscription into a revolutionary army.

In 1878, he defied social convention and his formidable mother to marry Gabriella de Balmondiére, a chain-smoking nineteen-year beauty who was ostensibly the daughter of a French merchant, but who was in fact Caroline Horsfall, a fugitive daughter of Yorkshire gentry. The reasons for the deception are unclear, but Gabriella’s true identity became the basis of an extraordinary family secret which endured until the 1980s. The deception was so audacious that, as James Robertson says in his introduction, it would barely stand scrutiny as the plot of a novel.

Finally taking possession of the family set at Ardoch, near Aberfoyle, his attention turned to politics. He was adopted and elected, on the second attempt, as the Liberal Party’s MP for Northwest Lanarkshire. He embraced a bevy of then radical causes including land reform, female suffrage, the iniquities of capitalism, amelioration of working conditions, Home Rule for Ireland, and proto environmentalism. Robert was frustrated with the House of Commons, and in a timeless series of observations labelled it a factory of hot air, the ‘national gasworks’ and an ‘asylum of incapables.’ In 1888 he was convicted of rioting in Trafalgar Square in defence of Freedom of Speech, wounded by a policeman’s truncheon, and served six weeks in jail. Seemingly burnt out after six years of intense political struggle, Cunninghame Graham retreated into a life of travel and of writing. He prospected for gold – unsuccessfully – and attempted, in disguise, to reach the Moroccan city of Taroudant, was captured and deported but managed to produce a bestselling travel book which he characterised as a ‘history of failure.’ Financially beleaguered, he unsuccessfully prospected for gold in Spain and was eventually forced to dispense with his crumbling family pile. Devoting himself to a life of writing, a plethora of books and articles followed on diverse subjects from the Spanish conquest of South America (and horses associated with it) to Scottish short stories and the lives of a dictator and a mystic cult leader.

In his final years as an esteemed writer and distinguished elderly gent, Cunninghame Graham embraced Scottish nationalism and in 1934 became the first President of the Scottish National Party, then a tiny fringe party struggling to make its voice heard, far removed from today’s powerful, if troubled giant. Ahead of his time as ever, he was a civic nationalist who asserted that nationalism was: ‘The first step in the international goal which every thinking man or woman must place before their eyes.’ Without nationalism, he argued, true internationalism was impossible.’ Cunninghame Graham died in 1936 on a literary pilgrimage to Argentina and was given a state funeral. His body was shipped home for burial on his ancestral lands at the island of Inchmahome on the Lake of Mentieth. Eulogised as a cultural figure of national importance, today he is relatively little known amongst the public.

Jamie Jauncey’s biography of R.B Cunninghame Graham is not a hagiography. It makes clear that its subject had his faults. He was prone to vanity, impulsiveness, recklessness, and moments of excess and poor judgement. He was far from immune from the prejudices and assumptions of the 19th century. His tendency towards holding contradictory positions was most apparent in his ability to reconcile his elite social status and rarefied lifestyle – he was fond of reminding people that he was a descendent of Robert II – with his political convictions and his championing of the oppressed worker. More concerningly, he seemed less than bothered by the unhappy reality that his family fortune was based upon the proceeds of slavery, yet at the same time deplored racism and the exploitation of indigenous peoples. He cared deeply about the welfare of animals yet purchased horses on behalf of the British Army for certain death in the First World War. Jauncey argues that these paradoxes and inconsistencies make his uncle a human being. And it is impossible to read this biography without agreeing that Cunninghame Graham was essentially a kindly and compassionate man who was motivated by altruism and a sense of outrage in the face of injustice.

At times, reading ‘The Adventure of being Cunninghame Graham’ feels akin to eavesdropping on a multi-generational family conversation played out in the pages and margins of texts. The book engages with and explores family memory, the collective memory of past people and events shared within a family. The Cunninghame Graham family have lived with Robert’s story for nearly a century, carefully guarding his memory but for the most part, disregarding his politics. Cunninghame Graham both created and inspired a literary culture which was enthusiastically embraced by the author’s late mother, Jean Cunninghame Graham, who penned her own biography of her beloved great-uncle: ‘Gaucho Laird.’ Jamie’s book is frequently in conversation with Jean’s, with mother and son examining and re-examining the life of their ancestor in light of their own preoccupations, and this lively intertextuality is one of the book’s conspicuous strengths. Other family members, now deceased, had been known to write their own opinions in the marginalia of biographies. Jamie’s grandfather’s writing appears, peppering the family’s copy of a particular book with ‘factual corrections and the word ‘no’ followed by exclamation marks.’ Biographers quizzed the family, who in turn questioned the biographers. The author’s mother hero-worshipped Cunninghame Graham, who she remembered as a generous elderly man from her childhood, who thrilled her with a demonstration of the lasso on a summer’s day. Her perpetual talk of his life and adventures so bored her son that by the time he was a teenager, by his own admission, he was heartily sick of it all. The book is also the story of how Jamie, once disinterested, came to be fascinated by Robert. Jamie’s life, which itself has included episodes of international adventure beyond the experience of many – not least a surprise appearance on the set of Monty Python’s Life of Brian – is interwoven with his account of his great-uncle’s biography. The resulting book is a rich and rewarding canter through family memory, cultural history, and political and literary biography. Yet with R.B Cunninghame Graham, it remains a struggle to perceive where the mythology ends, and the reality begins.

There’s an impressive monument to Don Roberto in Gartmore village.

Correction – After Trafalgar Square CG was sentenced to 6 weeks, not six months. Otherwise very fair review of an important book.

Fixed, thanks Rob

To bring a bit more balance, a more expanded (and fairer) description of Gabriela: ‘Gabriela Cunninghame Graham’, (Carrie or Caroline Horsfall, 1861-1906), was the wife of Cunninghame Graham. Despite being in the shadow of her husband’s renown, Gabrielle was also a woman of extraordinary talent; a writer, a poet, a botanist, and a traveller who distinguished herself as one of the literary characters of her age. Gabriela travelled in Spain and Portugal, and with her husband Robert in Morocco. In later times they journeyed in Mexico, Texas, and other areas of South America and the United States. Gabriela wrote many historical, biographical and topographical sketches, but is best known for her two-volume biography Santa Teresa: Her Life and Times (1894). The reasons for her changing her name are ‘unclear’, and remain unclear to date.