Scotland, Slavery, British Imperialism and Understanding Our Histories

The nature of Scotland, how Scots were treated throughout history – and the scale and how they were oppressed, has always been a contentious subject.

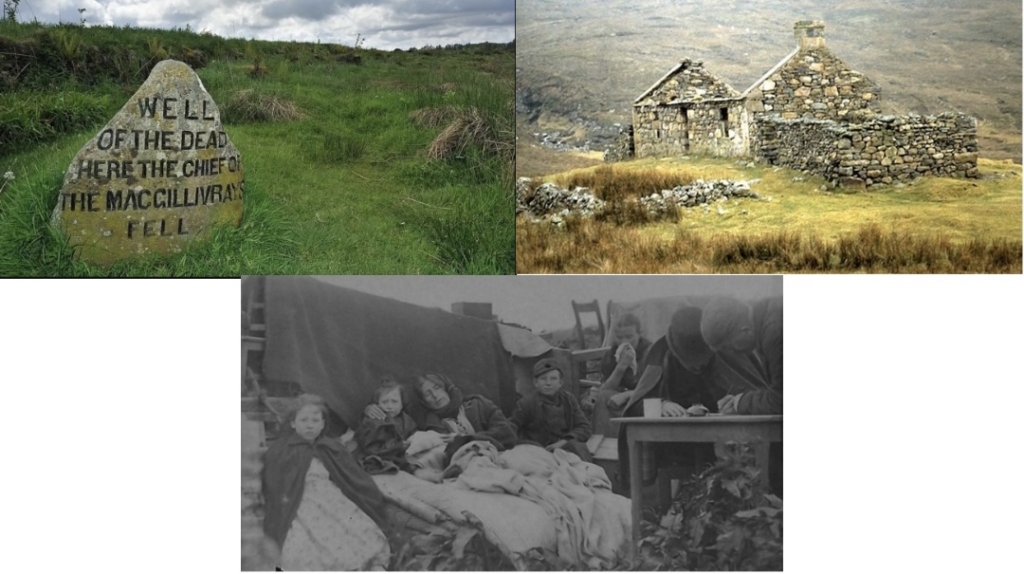

There has been heated debate through the ages about the character and severity of various massacres, the Highland Clearances, Scotland’s treatment in the Union, and the role of Scotland in the British imperial tradition that was Empire.

A wealth of detailed historical scholarly research has also added significantly to understanding Scotland’s past and the factors that made us who we are today. None of this is just arcane and about the past. Reflecting on how Scotland evolved, the internal and external forces that shaped us, and our role in the world has implications for how we see Scotland now – and how we imagine and create our potential future.

In recent years one counter-strand has become more prominent which challenges this – or is wilfully oblivious. One section of Scottish nationalism has become more and more impassioned and indignant with the historical treatment of Scotland, positioning the treatment of the nation and people within a framework of victimhood and seeing Scots as being done to, oppressed, having their freedom taken away and treated as lesser people.

In the past week someone called Sara Salyers tweeted the fact that she had identified a document which, she claimed, provided evidence that after the failed 1745 Jacobite rebellion thousands of Scots had their freedom taken away and were deported.

She wrote confidently that ‘thousands’ of Jacobites were sold as ‘slaves’ in the Caribbean post-1745. More than this, she and others then used this to claim that Scots were the victims of ‘genocide’ – meaning an attempt to wipe out large numbers of Scots as a people and eradicate them. These assertions were viewed and commented upon favourably thousands of times. She stated that:

In fact men, women children were slaughtered indiscriminately, evicted indiscriminately, 1000’s sold as slaves. The most populous part of Scotland, emptied. Survivors were subject to ‘civilisation’ by the same veterans who had slaughtered & evicted their people. Genocide.

This was rebuffed by numerous academics, professional historians, researchers and people who know Scottish history. It was pointed out that the document Salyers had created was in its contents ‘fake’, its assertions false such as the banning of the bagpipes in the aftermath of 1745, and that any deportations and indentured labour could not be equated with slavery.

Her intervention brought forth dozens of supportive comments such as: ‘Has there ever been an apology or step towards righting the wrongs. All we in Scotland want is our country back, and no longer ruled by another country.’ Another asserted: ‘I would like an SNP MP to propose that the UK Government formally apologise for their behaviour after Culloden in particular for those sold into slavery.’ Many referred to Tory minister Penny Mordaunt and recent remarks in the Commons about Scotland claiming, ‘she would love for it [deportations] to happen again.’

Historians such as Stephen Mullen of Glasgow University challenged such attitudes: ‘We’re at the stage of fake document/meme misinformation to claim Scots were sold as slaves.’ He stated categorically: ‘The defining characteristic of slavery is the legal ownership of people as property in society. You don’t get to retrospectively redefine it and apply it to aspects of Scottish history to suit an agenda. No white Scots were enslaved.’

Murray Pittock of Glasgow University pointed out that after Culloden in 1746, hundreds, not thousands of Jacobite supporters were transported to the Caribbean. They endured horrendous, dehumanising conditions and were forced to undertake seven years of forced labour, but not as slaves, Pittock noted. Rather: ‘They retained rights of personhood,’ he said, continuing: ‘And they were not subjected to the extreme punishments such as torture, castration or death normally visited on slaves if they escaped from their master.’

None of the above is to underplay or diminish the brutal conditions which many Scots experienced in the past – as well as English, Welsh and Irish people – at the hands of capitalists and landowners – aided by the forces of law and repression. It does not respect or honour the suffering of past generations to inaccurately describe what people went through, and to confuse and conflate for example indentured labour with slavery, or the experience of black Americans who experienced slavery in their millions with that of white Scots. And alongside this there is the collusion of many Scots in the British imperial project, Empire, slavery, which cannot be whitewashed away by a pretend and false version of Scottish history.

[ see also On Myths of Genocide ]

Scotland’s Past matters in the Present

This has an impact on the present day. Salvo, the campaigning pro-independence group of which Sara Salyers is a leading member, are not content with the above false interpretation of Scottish history. In the same week they claimed that the pre-1707 Scottish Parliament was an embodiment of popular sovereignty, and that citizens had the power to challenge any law. This allegedly, in an age of feudalism and pre-democracy when the people of Scotland had no real say in the governance of their land – and the idea of ‘popular sovereignty’ had yet to be heard of or invented.

These debates echo in the present. If and how Scotland wants to have an independence referendum and/or independence, is according to groups such as Salvo very straightforward. All it entails is asserting the collective ‘sovereignty of the Scottish people’ – while remaining vague about how that might manifest itself in a way on which the vast majority of Scots people could agree.

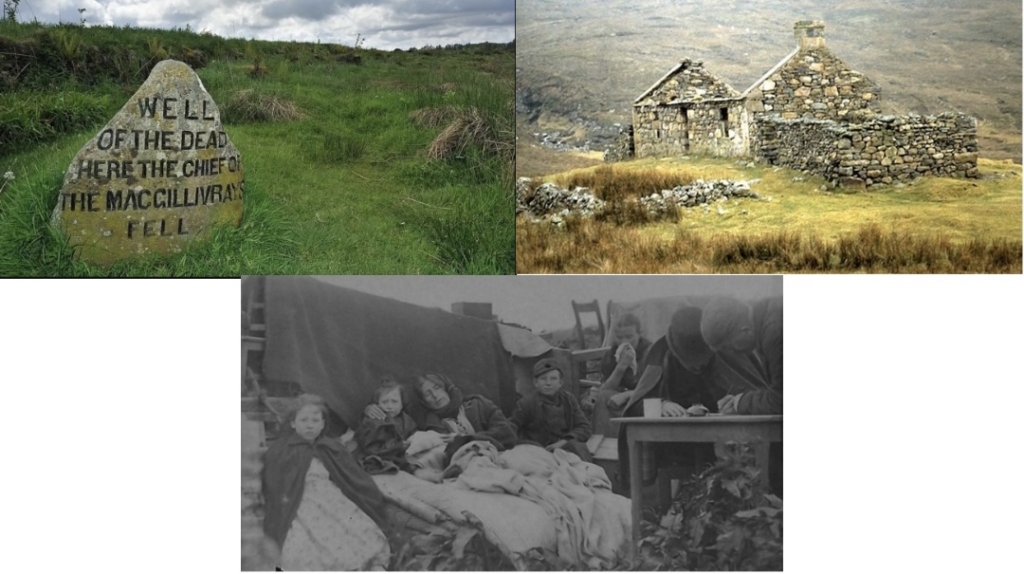

Then there is the nature of the British Empire including the role of Scots, and the responsibility of prominent Scottish figures at the height of slavery and imperialism for what happened. On the latter a major controversy has run for several years on the statue of Henry Dundas in Edinburgh and the description on the plaque underneath that explains his role in slavery (which has this week been the target of vandalism and temporarily removed).

Historians such as Tom Devine see Dundas as an abolitionist who played for time until there was a parliamentary majority for abolition. Whereas Geoff Palmer, who headed an Edinburgh City Council review, views the delaying tactics of Dundas on abolition for thirteen years – from 1792 when he was Home Secretary to abolition of slave trading by British ships in 1807 – meant that an additional 630,000 people were enslaved than otherwise would have been.

Besides this, is the never-ending argument about whether Scotland has ever been or is presently a colony. Any cursory examination of social media and posts on Scotland will find venomous expressions that Scotland was indeed treated by England as a colony, meaning that it was violently repressed and occupied, and its culture and traditions suppressed. Salvo earlier cited declare with certainty on their website that: ‘Scotland is either a partner in a Union of two countries or it’s a colony of England.’

Various moments in history are cited to validate this, including the 1707 Treaty of Union when Scotland and England together formed Great Britain. Such accounts never take incorporate the nature of the 1707 settlement, born in an age of pre-democracy and absolutism, when neither the Scottish or English Parliaments spoke for the peoples of their respective nations.

The 1707 compact saw Scotland lose its Parliament, but its autonomy in other areas of public life and civil society remained. Specifically the Kirk, local government and Scottish law – ‘the holy trinity’ which preserved institutional Scottishness and contributed to a distinct popular Scottish identity. Subjugation, assimilation or conquest, as happened to Wales and Ireland, this was not; Scotland remained a distinct legal entity in the emerging union, not a colony.

None of Scotland’s debates or controversies happen in isolation, although sometimes you may get that impression from some of the more impassioned perspectives. Some propose a Scottish exceptionalism, that ‘our’ nationalism is unique in the world of nationalisms and not informed by some of the characteristics underpinning the dark side of it that happen the world over. There is a tendency of over-assertion and over-claiming, which sometimes comes from frustration and wanting to differentiate the country as much as possible from England.

Scotland’s debates are part of a global conversation about coming to terms with the legacy of Empire, imperialism, colonialism and slavery (and which of course still exists in today’s world, including shamefully the UK).

David Leask in The Herald drew connections between the false claims and histories of some Scots and the language and paranoia of white supremacist nationalists in the US and elsewhere. He cited the example of Gavin McInnes founder of the ultra-right ‘Proud Boys’ who were an integral part of Trump’s attempt to overthrow US democracy on 6 January 2021.

McInnes was born in Hertfordshire, grew up in Canada, and is of Scottish descent, and said of Scotland a few years ago: ‘If Scots did grievance culture the way everybody else does, we’d get our own month’, concluding: ‘Yes, we were slaves’.

This is the ultra-right, white supremacy, racist, xenophobic worldview that some Scots collude with, and establish a common agenda with, if they talk about white Scots being treated as slaves. While endlessly going on about our progressive and inclusive nature – and our tolerant, benign and civic nationalism – such perspectives are making united cause with some of the most virulent, reactionary, bigoted forces in the developed world.

Scotland was not, never has been and is not a colony. Scots were not treated as slaves with their freedom, rights and humanity removed. The battle over Scotland’s history cannot allow false claims, false documents and a false sense of victimology to gain traction and adherents, as this will only aid a politics and sentiment which increasingly aligns with forces of the ultra-right and reaction. And the process of uncovering and coming to terms with our own histories and part in British imperialism, colonialism and slavery, rightly has to go on.

In a worldwide struggle between the forces of darkness, racism and conspiracy theories, and upholding facts, evidence, the power of reason and championing liberty, there should be no room for ambiguity and uncertainty about which side we are on.

Scene: Caribbean-1750’s ” C’mon son, yere indentured Labour, yere no like these black###’- GH citing Leask is enough for me..

It’s interesting that the alt-right in America also use the ‘fake news’ of the enslavement of Jacobite prisoners in its attempts to deracialise the historical institution of slavery and thereby ‘cancel’ the culture that casts that episode and its subsequent repercussions down to the present day as an instance of America’s institutionalised racism and black victimhood.

Political prisoners were condemned to periods of indentured labour in British, French, and Spanish colonies. But such penal servitude was not slavery. The periods of indenture were limited, with prisoners regaining their freedom once their sentences had been served. Also, unlike slaves, they (and their children) retained their moral and legal status as persons and were not treated as chattels.

Scottish nationalist ideology is full of such ‘fake news’ and conspiracy theories, much of which was invented by the Edinburgh Tories in the 19th century to create a spectacle of national pride and romance that could provide a focus for patriotic sentiment within the Union with out ‘Auld Enemy’. This invention produced, among other things, our present nationalist historiography of grudge and grievance, which could be celebrated and played out in ‘home international’ competitions and music-hall banter.

This ‘fake’ historiography Scotland as an imagined community is as harmful to our future as kailyairdism was to our culture in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. We really need to deconstruct it in order to get on.

Scottish indentured servants did not choose to enter these contracts willingly. They had either been forcibly removed from their homes during The Clearances, or forced into the contracts as what we would now call “Enemy Combattants” after Culloden.

The main difference between Slavery and Indentured Servitude as stated above, is that a servant retained some rights of “personhood” and would be free after the contract. But let’s not forget that these people were once free, and were forcibly removed from their homelands (oftentimes never to see their kin or homeland again), and forced into rough labour that occasionally resulted in death or dismemberment.

A limited period of imposed servitude versus a lifetime as chattel is a good clear distinction to make, but let us not whitewash the horrors, degradation, and often fatal risks to personal wellbeing that came with Indentured Servitude.

Let’s also not forget that these Indentured Servants were often not allowed to return to Scotland, and their descendants are not welcome to emigrate to the UK to this day, unless under very specific conditions that apply to other foreign nationals. It was a ruthless mechanism emloyed to clear Scotland of many able-bodied men and women, thereby suppressing any further resistance to British control and subsequent Colonisation.

You were doing fine there, David, until you wrote: ‘[Penal servitude] was a ruthless mechanism employed to clear Scotland of many able-bodied men and women, thereby suppressing any further resistance to British control and subsequent Colonisation.’

Indentured servitude was a widespread institution in Europe at that time. Everyone did it to penalise common criminality and treasonous activities; in Britain, the Jacobean state used it before the Revolution just as much as the succeeding Hanoverian state.

Indentured servitude was indeed a brutal regime. It’s also true that most indentured servants from these islands ceased to be ‘English’, ‘Irish’, ‘Scots’, and ‘Welsh’ (or collectively ‘British’) on their release and became colonists and later citizens of the nations to which they’d been transported.

But it was never a mechanism of ethnic cleansing in the service of British colonisation of Scotland. As Gerry points out, Scotland was never ‘colonised’ or assimilated; it’s culture was never ‘cancelled’ by conquest or mass immigration. (If anything, Britain was colonised by the culture of the 18th century Scottish Enlightenment following the Union.) That’s just one of the nationalist ‘alt-right’-type myths that pollutes our political discourse.

Thanks for this thoughtful piece. The profile Salvo has achieved within the independence movement is an unwelcome development, heralding a turn towards ethnic nationalism, and sect-like magical thinking. For if Scotland is a colony, then who are the colonists, and what is to be done with them? Salvo’s a-historical take on Scotland’s past and current position within the Union is proving attractive to some in the independence movement, perhaps because its scholastic approach to sovereignty – based largely on a few misinterpreted historical documents – absolves them of the hard slog needed to convince our fellow citizens. More widely, the prominence it has gained underlines the poverty of theory within the independence movement, and the lack of serious political analysis of the social movement and the social forces underpinning it. All the more important that the inspirational work of Tom Nairn should be remembered, celebrated, and developed further.

I would take this further. It is essential that the independence movement looks to the future for our justification, not the past. We can learn from the past but must be aware that it is subject to (mis)interpretation as with Salvo. There is a singular lack of class politics or awareness in much of these debates. To ignore this is to fail to see how the class interests of the elite was a moving force behind unionism in the past and remains so today. There is plenty of analysis of how parts of the working class were hoodwinked into supporting Toryism and a limited Labourism. Lets draw on that to understand the forces behind unionism now. The way in which populism has captured many with its easy ‘magical’ solutions must be countered by a sober well informed insights. A lot to do but it will be worth it.

Agreed Cathie. As I wrote in 2018:

“The case for Scottish democracy rests on the appalling mismanagement of our society and our economy by successive governments we didn’t elect, the abject failure to protect and develop the potential of people living in Scotland, the reality of whole communities disfigured by poverty and the toxic legacy of the British State. It does not rest on pretending that we experienced genocide.”

We down in Dumgall didn’t elect the successive Scottish governments that have appallingly mismanaged our public affairs either. Does that make a case for ‘Dumgall democracy’ and an independent Dumgall government?

I’m not sure the independence movement is all that interested in ‘theory’ and ‘structural analysis’ (it’s far too distant from people’s ‘real-life’ concerns, an intellectual indulgence, something that can be set aside until after independence has been achieved, etc.); it’s much more interested in getting enough votes to get Independence over the line, and any old populism will do to get those votes. Who cares whether a ‘Yes’ voter supports independence because they believe ‘alt-right’-type nonsense or they believe that independence is a necessary condition of a brave, new postmodern Scotland or they’re moved by the anglophobic strains of Flower of Scotland… As long as they vote ‘Yes’, that’s all that matters.

I’m not suggesting we force theory down everyone’s throats but that we’re informed by it in what we try to do

Indeed, ‘an unexamined life is not worth living’. We should continually be examining the assumptions on which our action depends (‘doing theory’) and analysing the conceptual structures that inform our propensity to behave in certain ways rather than others (a.k.a. our ‘beliefs’).

The trouble is that we’ve largely been schooled to consume information (learn facts) rather than cultivate our understanding (learn how to interpret and evaluate evidence) and, as a consequence, we generally lack as a society any great ability to ‘do theory’. Instead, we generally just swallow whatever information, misinformation, and disinformation that’s served up to us (or ‘rammed down our throats’, as you put it) on the basis of whether or not it’s to our taste; that is, according to whether or not it fits our existing prejudices.

‘This is the ultra-right, white supremacy, racist, xenophobic world view that some Scots collude with’

I have no doubt that there are ‘some Scots’ who do so but – importantly – they are a negligible group.

This is an example of a ‘tendency of over-assertion and over-claiming’ which Gerry Hassan referred to earlier in his piece.

Not if you read the complete sentence that Gerry wrote, it isn’t.

‘This is the ultra-right, white supremacy, racist, xenophobic worldview that some Scots collude with, and establish a common agenda with, IF THEY TALK ABOUT WHITE SCOTS BEING TREATED AS SLAVES.’ [My emphasis]

It only over-asserts if you ignore, as you do, the qualifying ‘if’ clause.

If Stephen Mullen claimed “The defining characteristic of slavery is the legal ownership of people as property in society.”, he is simply wrong. There are plenty of ways that people can be enslaved illegally (the British Empire did this a lot), informally, extra-judicially and extra-nationally; and racialised chattel slavery of the Atlantic type is not the only form of slavery, though one of the most heinous. Slavery can also be a temporary condition. Michael Moore views the USAmerican prison complex as a modern development of USAmerican slavery, for example.

There is a pertinent chapter 6: Indenture, Transportation, and Spiriting: Seventeenth Century English Penal Policy and ‘Superfluous’ Populations, by Anna Suranyi, in Building the Atlantic Empires: Unfree Labor and Imperial States in the Political Economy of Capitalism, CA 1500-1914, Ed John Donoghue and Evelyn P Jennings, which looks at the blurring of these categories in the context of private and state relations over time. This could involve the abduction of children to be sold into servitude, too young to contract even if not kidnapped. Interestingly, the author says that Barbadian servants were allowed 1 month to claim kidnapping after arriving. And transporting political prisoners to work expected-life sentences perhaps on trumped-up charges in malarial colonies is surely slavery too. The author suggests that lax enforcement of laws (some of which did not apply to Scotland or Ireland anyway) amounted to official connivance in the illegal trade in warm bodies. Obviously these systems could facilitate horrendous abuses.

But English vagrants, children and political troublemakers were as much in danger as Scottish crofters. If you want to see a description of genocide by clearance, there’s a BBC Storyville documentary on one of the Architects of Transfer. https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m001q7qz/storyville-blue-box?page=1

And I’ve seen nothing in the Scottish histories on that level. For example, Arab Palestinians didn’t make up elite colonial army units the way Scots did it the British Empire.

These offences were done under the British imperial quasi-constitution where the monarch holds the lives and deaths of subjects in their hands; hence even children could be abducted under Royal warrant and enslaved on the Elizabethan stage, not just unlucky coastal pub drinkers and foreign sailors coshed and pressed into the Royal Navy. I have no doubt that some Scots were forced into slavery, but these were not the ones voluntarily and informedly entering into an indentured contract which was subsequently honoured. History is messy. Treat historians who pretend otherwise with legal niceties and neat categories with suspicion.

Stephen Mullen isn’t ‘simply wrong‘. Historically, the defining characteristic of slavery is the legal ownership of people as property in society. As Stephen says: you don’t get to retrospectively redefine it (as you do) and apply it to aspects of… history to suit an agenda. That’s fallacious reasoning.

You cited a chapter dedicated to ‘Indenture, Transportation, and Spiriting’ in an collection entitled ‘Unfree Labour’ in attempt to undermine a widely acknowledged definition of what slavery is? I’ve just checked the Suranyi chapter and she makes the clear distinction in the status of enslaved people and indentured servants in late 17th century Barbados:

“For example, Barbadian planters sent a petition to Oliver Cromwell in 1655 to ask for relief from military service because of the dangers of leaving behind potentially rebellious African slaves, and Irish and Scots servants, the latter of whom were “formerly prisoners of war and ready to rebel.” They concluded by asking for more English servants” (p.141).

If you are claiming Suranyi is arguing indentured servitude was slavery, provide the citation.

The British certainly exploited multiple forms of unfree labour across the Empire, but chattel slavery was distinctive. As I have noted time and again, slavery is, and always has been, the legal ownership of people as property in any society. That applies to classical models of slavery (especially Roman slavery, which is viewed as the ‘ideal model’) and colonial slavery.

I would advise you familiarise with the historiography, including the Suranyi chapter and J. Brown’s ‘Servitude, slavery and Scots law: historical perspectives on the Human Trafficking and Exploitation (Scotland) Act 2015’. Legal Studies. Author accepted manuscript version here: https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/71187/1/Brown_LS_2020_Servitude_slavery_and_Scots_law_historical_perspectives_on.pdf

Eeek! I spy Angels!

@Stephen Mullen, assuming you are not a fraudulent impersonator of the Glasgow University lecturer, here is my response.

A couple of red flags: you don’t link to, or quote, any “widely acknowledged definition” of slavery. And you completely misrepresent my distinction of slavery and indentured servitude (parsing failure, or straw man?).

The idea that slavery is essentially a legal conception:

1. privileges the lawmakers of Empire

2. assumes that any legal fictions are definitive and representative of real-world actions

3. rejects the lived experiences of the victims of slavery

4. supports the false narrative that the British ‘abolished’ slavery (by legal means)

5. ignores the many historical cases where slavery was not legalised

6. ignores illegal, extra-judicial, informal and extra-national forms of slavery

7. supports British (Roman?) claims of universal jurisdiction

8. ignores the (sometimes successful) legal challenges made against the inconsistent status of enslaved people in the British Empire

9. assumes that a fictitious racial model can be consistently legally applied in the real world

10. ignores that the British Empire often exerted its power abroad using the Royal Prerogatives, for example by Royal Charter of enslaving companies, by dictat rather than legislature. Dictats don’t have to meet the same standard.

11. ignores standard models of consent.

I have looked up a number of internationally-recognised definitions of slavery. They speak of status, practice, condition, forced servitude, but none of the ones I looked at mention a legal requirement.

Taking only a few of these points:

Reading Keith Lowe’s accounts of Korean ‘comfort women’ enslaved by the Japanese Empire during WW2 there is no formal legal justification, but abductions, false job offers, contractual justifications appear. But you argue that these women were not enslaved because the Japanese authorities did not set out some legal proclamation.

The case of George William Gordon of Jamaica I brought up in another comment is also an illustration of how precise definitions of racial categories or nationalities is impractical, and how much enslavement must have relied on convention throughout history. There will have been some black Scots, if we accept those categories, perhaps from unions of Scottish planters and enslaved women from West Africa, and some of them lived in Scotland. If they were sent to an island run on racialised chattel slavery lines, they might have ended up enslaved due to the colour of their skin, regardless of whether they had a piece of paper or not.

Anyone abducted, or below the age of legal consent to contract, or otherwise forced into servitude, is categorically different to any capable adult freely signing an indentured contract; and if the indentured servant is deprived of the rights and protection of that contract, is abused and treated like property, their experience and condition may be that of enslavement.

Anyone abducted, sold, violated, etc in Africa or on the Atlantic as part of Britain’s triangular trade can have strong and correct views about their condition as slavery without ever being aware that some statute lay somewhere on some piece of paper. To deny their perspective is a disturbing form of ahistorical gaslighting. Your argument is that British authorities had jurisdiction over these foreign lands, and that the crimes committed there were somehow ‘legalised’:

https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/slavery-convention

None of this detracts from the status of British racialised chattel slavery as one of the most, possibly the most, heinous forms of slavery in our histories.

And since the British Empire today retains one form of enslavement on its book, naval impressment, a Royal Prerogative and later relation to Roman galley slavery, we can clearly discern that the legal existence of a form of slavery is distinct from the actuality of slavery. While British Imperial forms of slavery that legally still exist should be challenged, it reasonably does not take as high a priority of action as opposing real-world modern slavery today.

Slavery is awful and horrifying, wherever and whenever it occurs, but it is not the defining feature of colonialism. A good source on this is Robert J.C. Young, Postcolonialism, a very short introduction, 2nd edition, Oxford University, 2020. One pattern of colonialism involved slavery and murder. Another pattern involved taking control of a land and its people – as in India, New Zealand and many other places. If you read Young’s book, it is clear that (a) colonialism in its many forms has been a massively destructive global process, and (b) there are many parallels between the struggle to decolonise that has taken place around the world, and what is happening now, today, in Scotland. For example, decolonizing involves achieving self-determination, restoring ownership of land, and recovery of Indigenous knowledge and culture – all of these are live issues in Scotland today. The situation in Scotland is complicated because – as in other countries – Scottish people were both the victims and perpetrators of colonialism. Moving forward – toward independence and beyond – involves facing up to both of these things. There is a strong thread of unearned privilege in our culture and psychology, alongside an equally strong thread of subservience and a legacy of loss and trauma. There is much we can learn from the many peoples and countries who have been much more open than us in acknowledging and moving on from colonialism. Gerry Hassan has made a massive contribution to our intellectual and political life for many years. But I read his article as saying that we should not be thinking or talking about colonialism at all. Maybe I have misunderstood his argument. But if this is what he is advocating, l then I strongly disagree. Colonialism is not a simple thing. It has operated in different ways in different places and at different times. It is in each of us – in our heads and emotions – as well as in our social structures and laws. It needs a major collective effort to understand the specific way that it has operated in Scotland.

Thanks for your common sense contribution- this thread had too many arcane, one- upmanship ,(who cares?)over-excessive academic comments. Our situation is nuanced, but colonisation is real to those who feel it. Look at the snash Alasdair Gray had to endure for his perfectly understandable contribution? One can only hope that the population ebbs+flows, post 2014, have resulted in a pro-Yes increase, as indigenous youth -who-stay, outnumbering incoming No-voting New Scots, with hopefully, those EU immigrants who stayed, realising they’ll feel more comfortable in a Scotland that more resembles Ireland than England.

‘…this thread had too many arcane… over-excessive academic comments’.

‘One can only hope that the population ebbs+flows, post 2014, have resulted in a pro-Yes increase, as indigenous youth -who-stay, outnumbering incoming No-voting New Scots…’

This is just ‘alt-right’-type populist bullshit, which seeks to demonise ’the [so-called] intellectual elite’ and immigrants. It’s precisely the sort of poison that needs to be called out.

In seeking a definition of ‘colonialism’ (i.e. in seeking to identify what is essential or intrinsic to colonialism), you still can’t do better than take a look at Frantz Fanon’s seminal collection of essays, The Wretched of the Earth.

As Fanon points out, slavery, conquest, settlement, et al, are not intrinsic to colonialism; people can still be colonised in the absence of these things (though they all can be the means by which colonisation takes place). What is essential to colonialism is hegemony and, in particular, the hegemony of a dominant ideology. Colonialism is any process by which one ideology comes to dominate a people’s collective ‘mind’ or culture.Through his critiques of nationalism and imperialism, Fanon presents an analysis of how we use language to establish or ‘vocalise’ our identities (e.g. as ‘coloniser’ and ‘colonised’, ‘native’ and ‘outsider’, ‘victor’ and ‘victim’) and to thereby teach and psychologically mold us in out respective roles in the [Hegelian] Master/Slave relationship. Decolonisation then becomes the task of liberating ourselves from ‘mental slavery’; that is, of deconstructing the hegemony or ruling ideology that shapes and restricts us to our current identities. In one of the essays, ‘On National Culture’, Fanon highlights the necessity for each generation to rediscover this ‘mission’ of self-liberation and to fight for it.

Decolonisation thus does involve rejecting one’s victimhood and realising one’s self-determination. But it also involves rejecting the nativity and other identities one has been ascribed by the dominant ideology of one’s milieu. It’s decidedly not about rediscovering and restoring some supposedly ‘indigenous’ culture.

In his essay on National Culture, Fanon argues that, rather than depending on a fetishised understanding of precolonial history, we should build a liberation culture on our material resistance to domination. Fanon suggests that colonised people often fall into the trap of ‘precolonialism’ culture. This is a dead end, according to Fanon, for our ‘indigeneity’ or ‘nativity’ is itself a product of colonisation and part of the hegemony that the dominant ideology exercised over our collective ‘consciousness’ or culture. Any attempt to ‘return’ to the nation’s pre-colonial culture is ultimately an unfruitful pursuit, according to Fanon. The atavist emphasises traditions, costumes, and clichés, which romanticise history in a similar way as the colonist would. The persistence of national clichés and traditions demonstrates a fixed idea of the nation as something of the past, a corpse to be resurrected.

Fanon argues the colonised will ultimately have to realise that their ‘true’ culture is not a historical reality waiting to be uncovered in some Yeatsian return to pre-colonial history and tradition, but is a latency that already exists in the present colonial reality. Struggle and authenticity become inextricably and dialectically linked in Fanon’s Hegelian analysis. To struggle for liberation is to struggle for a space whereby in which a decolonised culture can grow.

A decisive turn in the development of the colonised is when they stop addressing the coloniser in their work and begin addressing themselves. This change is reflected in all modes of artistic expression among the colonised, from literature to pottery, to ceramics, to music, which become more innovative than traditional. Fanon specifically uses the examples of Algerian storytellers and bebop jazz America, whereby the artists delink themselves and their audiences from the self-image with which they’ve been colonised. Whereas the common trope of African-American jazz musicians was, according to Fanon, ‘an old Negro, five whiskeys under his belt, bemoaning his misfortune’, bebop was full of energy and dynamism that resisted and undermined the common racist trope.

For Fanon, liberation culture is then intimately tied to the struggle to disrupt and deconstruct one’s ‘given’ identity; an act of living and engaging with one’s present reality that gives birth to a range of innovative cultural products. Fanon summarised this idea by speaking of replacing the ‘concept’ with the ‘muscle’; the actual practice and exercise of decolonisation itself forms the basis of decolonised culture; the struggle for liberation becomes its own end.

Scots were never sold into slavery by the English; Scotland was never occupied by the English; Scotland was never ethnically cleansed by the English; Scotland was never pillaged of its resources by the English. That’s all ‘alt-right’-type grudge-and-greivance bullshit deployed to win some votes for Independence. If anything, it was the ideology of the Scottish Enlightenment – the so-called ‘Athens of the North’ – that colonised Britain, the rest of Europe, and the whole world subsequently.

There are many parallels between the struggle to decolonise that has taken place around the world, and what needs to happen in Scotland. One of the things that needs to happen is that it must ditch the ‘alt-right’-type grudge-and-grievance politics that hearkens back to a romanticised ‘Sir Walter Scottland’ that is itself a product of colonialism; namely, that of the 19th century Tory nationalists.

I read Gerry’s article as an appeal to do just that; to turn away from addressing the coloniser and start addressing ourselves instead; to delink ourselves and their audiences from the self-image of ‘victim’ with which we’ve been colonised, ‘Tae be yersel an tae mak that worth bein’.

As the great South[ern Up]lands poet and liberationist, Hugh MacDiarmid, said: ‘Nae harder job tae mortals has been gien’.

An excellent article. At last someone calling out Salyers and her Salvo brigade on the false historical narratives they are peddling. Something else you will find on the Salvo website is an article that claims people of English origin are “settlers”. This is the logic of their ‘Scotland is a colony” claim. It goes along with language definitions of nationhood and leads back to forms of ethnic nationalism. A very bad development in our independence movement.

Anybody familiar with song Brand New Day by Davy Steele , about Scots who had been cleared from Scotland , then subsequent “clearing” of indigenous peoples in Americas.

Is there any research into those transported/indentured/cleared ordinary Scots over the centuries – in distinction to the Sugar & Tobacco lords ?

__________

On a brand new shore on a brand new day

You kissed the ground where you had landed

Took one last look o’er a thousand waves

To the high high lands from where you were hounded

You could still smell the smoke from the black house roof

You could still hear the laugh of the carrion that fired them

You looked to the sky and you gave God’s curse

To the hard hearted laird who’d hired them

So how could you forget the anger and the hate

You felt inside when they robbed you of your pride

And caused you to wander

So you closed your mind to the pain of the past

Forged a new life , found a new future

And you swore in your heart that here at last

You’d would be no mans master

And you let the world know in the eyes of your laws

All would be free and created equal

THEN you swept through the land like a fire on the wind

Where you touched the earth the touch was final

Then on sacred land owned by ancient man

You found rich soil and precious metal

So you swept them aside with your guns and lies

With only the thought of your own survival

For all the fine words that were said to inspire

All the poor of the world , all the crushed and the homeless

Were drowned in the flood of your sole desire

To command so much power , it would make you shameless

For you forgot how it felt to be bought and be sold

To be sent far away to be owned by another

You forgot the one thought in the minds of the oppressed

Is to one day rise and make things better

https://youtu.be/OVzvepIP-XI

A fellow learner put me on to a peculiarly Scottish form of enslavement, that of colliers and salters, referred to in this Act:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colliers_and_Salters_(Scotland)_Act_1775

with coal workers officially described as living in “a state of slavery or bondage”, by previous legislation and custom. Unfortunately the Wikipedia page doesn’t link to the legislation itself, which is missing from legislation.gov.uk

The article I was referred to is called Serfs – Colliers and Salters. The legal status of slavery was repealed by later legislation, apparently, although I don’t know about the conditions on the ground (or underground). The article raises the important point about the hereditary passing on of the enslaved status (Head of household had an interest in their children replacing them) and the right to challenge enslaved status potentially requiring knowledge of the law, perhaps some degree of literacy and the means to mount a court case. How successful those challenges might have been, I don’t know.

It seems that Scotland might have had its own caste system, its version of Untouchables.