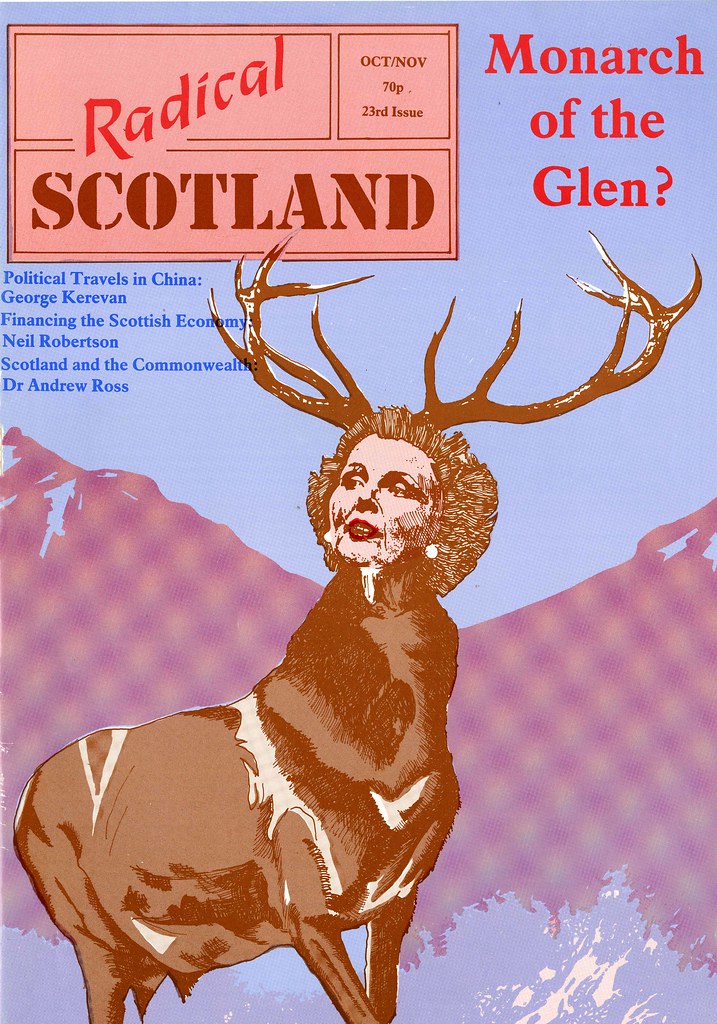

Radical Scotland: Making connections and the case for Scottish self-government in Thatcher’s time Part 2

Radical Scotland: Making connections and the case for Scottish self-government in Thatcher’s time. By Douglas Robertson and James Smyth.(1) Part Two: Setting the agenda for political change

In the early 1980s, Scotland was in a state of political turmoil. Following the failure of the 1979 devolution referendum to achieve a measure of self-government, the Labour Party and the Scottish National Party (SNP) were blaming each other, while Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives had come to power and declared any idea of “home rule” for Scotland dead. In-fighting had led the SNP to proscribe internal groups, with the express intent of expelling activists from the left-wing 79 Group. Meanwhile pro-devolutionist Labour activists were faced with a UK party which, fearful of seeing the Tories hold on to power for the long term, seemed to be backing away from the devolution project altogether.

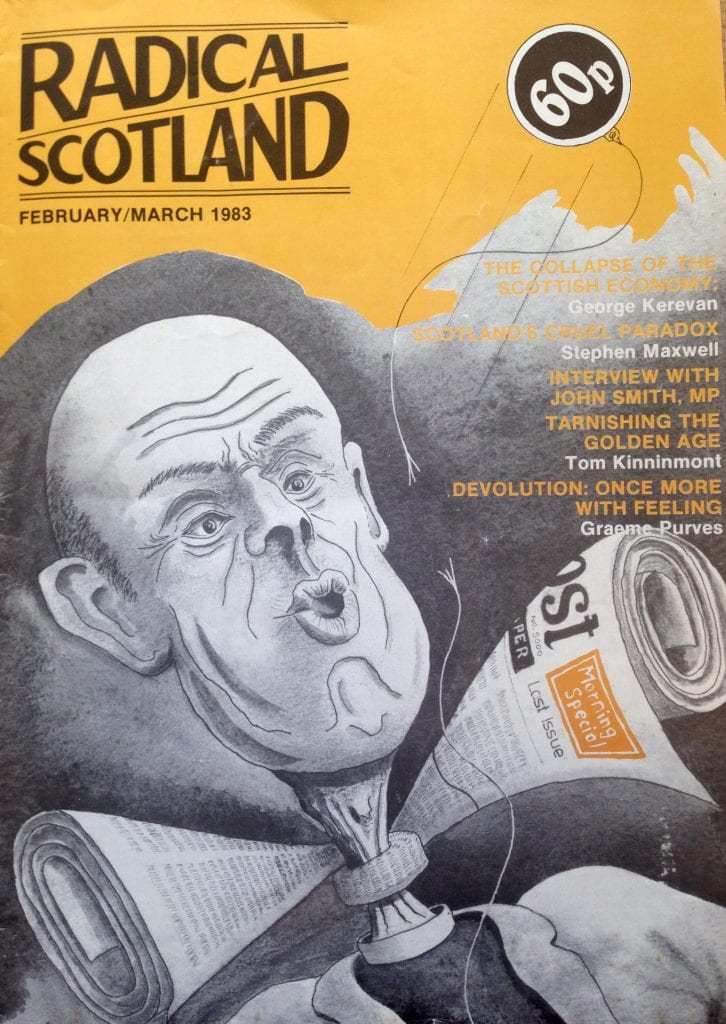

It was in this turbulent atmosphere that a collective of political activists, including the authors of this article, took over the little-known magazine Radical Scotland in 1983, with the aim of uniting sympathisers of all parties and keeping the dream of Scottish self-government alive.

Being essentially political activists, we were reasonably well-versed in how to set agendas and so utilise the press to that end. This was a symbiotic and productive relationship. Radical Scotland would publish articles on particular issues and individual members of the collective would then try to generate interest in them by briefing selected people across the Scottish media, whether newspapers, radio or television. There was then, of course, no internet. Political correspondents were happy to be fed in this manner, given that much of the mainstream political coverage at the time was both limited and dull. We were on occasions able to offer them a new topic, or an entirely different take on an old one. However, they did not always bite on what we considered to be the juiciest of offered morsels.

The magazine also quickly learned that it could utilise opinion polls to pose different questions on self-government, so we could offer up different, but authoritative answers to the mainstream media. Rather than simply include self-government as one policy item in a list of voters’ priorities – which in the context of the 1980s always ensured it came behind employment, health and nuclear weapons – the trick was to pose a question on how self-government could better address this or that issue. This moved the discussion away from just a checklist of issues to a position whereby self-government became the means to address each particular issue. Clearly, the cost of commissioning our own polls was way beyond the magazine’s negligible resources. However, Alan Lawson, Radical Scotland’s long-term editor, was a polling enthusiast and adept at piggy-backing our questions on to larger, recurring opinion polls. Producing such robust and authoritative poll evidence helped ensure that the magazine got regular mainstream media coverage. Given our contacts, we also fed the press material that, as a bi-monthly magazine, we could not do justice to publishing months later. This activity helped foster a number of mutually beneficial and productive relationships.

It was also part of Radical Scotland’s agenda to expose and lampoon those who opposed, or were deemed weak in supporting, self-government. But those were not the only targets. Any fatuous political or administrative officialdom, displaying varying degrees of pomposity, nonsense or hypocrisy, proved fair game. A prime focus of the I Spy gossip column was highlighting the failings of everyday political life and its administration. But this column was also used to illustrate just how politically well-connected the magazine was. We wanted, and needed, to show that we knew what was going on, to reinforce that we should be taken seriously.

As is common with gossip columns, many people used us to promote their own personal agendas, vendettas and political careers. A previous First Minister, Jack McConnell, then a Labour student activist and later a Stirling councillor, was a regular supplier, putting into the public domain many juicy titbits of sensitive political material. Though he attended at least one editorial meeting, he did not take up an offer to join the collective.

The magazine was also involved in recording and in its own way contributing to what transpired to be a major cultural shift. At the time of Radical Scotland’s launch there was a clear sense of a cultural resurgence, if not renaissance. The magazine was always fascinated by the relationship between culture, identity and national politics. Nature abhors a vacuum and in Scotland’s empty years under Thatcherism, in the absence of convincing politics, various cultural endeavours, broadly defined, sprung up to fill that void.

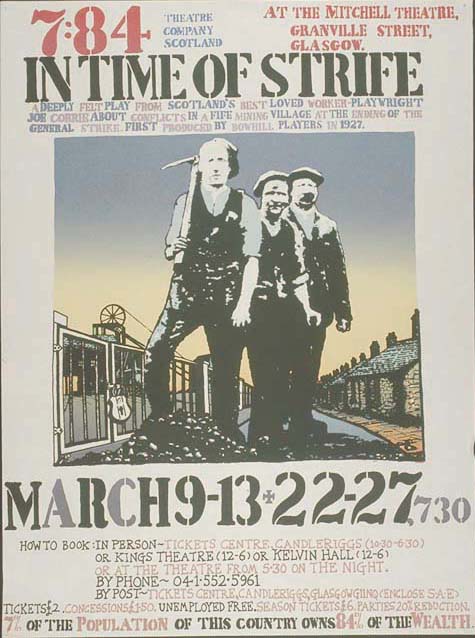

In literature, drama, music, history and art, the broad consensus was left-of-centre, if not overtly anti-Conservative. The bitterness of the miners’ strike served to further cement the political relationship between the arts and self-government politics. Not surprisingly, much artistic activity at that time was concerned with celebrating the threatened Scottish industrial working class. Numerous plays by theatre groups such as 7:84, Borderline, Communicado and Wildcat, as well as the literature of the likes of William McIlvanney, Janice Galloway and James Kelman, and the poetry of Liz Lochhead and Tom Leonard, provide ample illustration of that genre. Throughout its life, Radical Scotland reviewed books and events, often those disregarded by the mainstream press, in an attempt to give them a wider voice and audience. For example, the magazine was the first to review Iain Banks’ The Wasp Factory, Janice Galloway’s The Trick is to Keep Breathing, A.L. Kennedy’s Night Geometry and the Garscadden Trains and James Kelman’s The Disaffection.

The magazine also sought to play its own small part by encouraging new writing on the arts and history, so published short stories and poetry by aspiring new writers, such as Dilys Rose, Brian McCabe and the collective’s own James Robertson. Alan Lawson managed to secure a small grant from the Scottish Arts Council to pay for such contributors. In this, however, we never quite achieved what Planet was able to offer Wales, though some of Radical Scotland’s cultural content bears comparison with material published in the dedicated cultural periodicals, Cencrastus and Chapman.

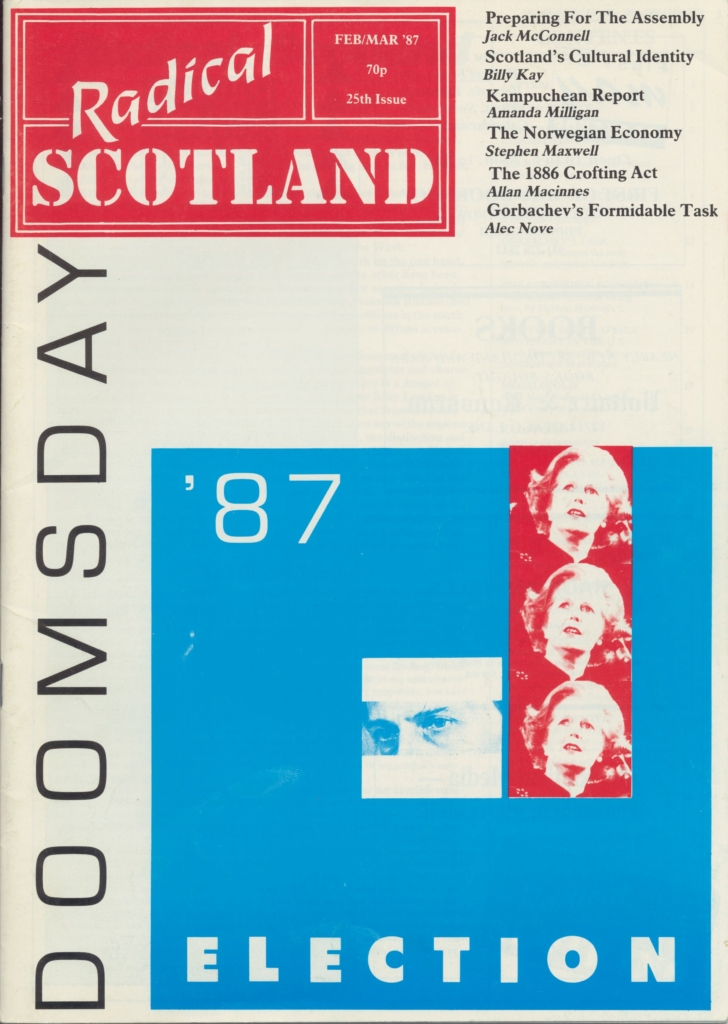

Radical Scotland’s real successes were in political agenda setting. One initiative reframed the Scottish political situation from being termed the ‘democratic deficit’, into the more popular ‘Doomsday Scenario’; while a second offered the technical means to move self-government ideas and debates forward, out from political deadlock, by advocating the adoption of a Constitutional Convention. Both became major political stories, in no small measure because of the time and effort expended on building up these solid media relationships.

The ‘Doomsday Scenario’ was designed to heighten expectations and put pressure on the Labour Party to decide what exactly it would do in the event of yet another Conservative electoral victory. (2) The term came to encapsulate the magazine’s political project. Once coined, following a weekend planning meeting at Edinburgh University’s Loch Tay Outdoor Centre, it was aggressively promoted by the magazine throughout the mainstream political media. The intention was to ensure that this became ‘the’ issue which dominated Scottish political debate in the run-up to the 1987 General Election. The focus was our target audience, the country’s political classes, and in that endeavour we succeeded

As noted earlier, this was the issue that the magazine thought Labour should be forced to address, though in the event it never did. The reality was that no other political party could deliver self-government, and Labour in Scotland was never likely to go down a separatist road, though certainly some within its membership toyed with that idea. Radical Scotland sought to encourage such thinking, not least as a means to harden up the Party’s commitment to the self-government project.

The General Election of 1987, therefore, marked a crucial turning point, when self-government became the key demand of all Scottish political parties with the exception of the Conservatives. Working out how exactly to deliver it, when Labour eventually won a General Election, was to be the task for the aforementioned Constitutional Convention. Floating the idea of a Convention and ensuring that it was picked up and carried forward by civic Scotland and the political parties, was the magazine’s other success.

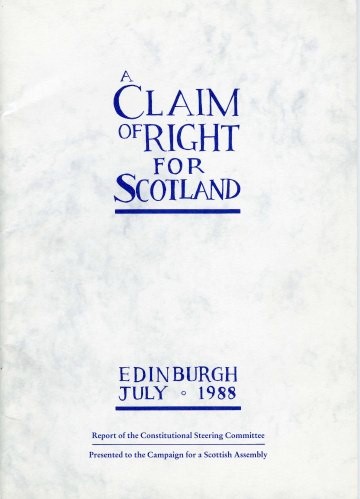

Despite 1987 delivering another Conservative victory, Labour managed to hold together and there was no internal nationalist breakaway. That said, five years on and after yet another Conservative General Election victory, one small group headed up by George Galloway and John McAllion, both then Dundee MPs, staggered away under the Scotland United banner, a short-lived grouping which had Scottish Trades Union Congress support, before it quickly sobered up and fell back in line. What was significant about that event, however, was that Labour in Scotland found itself being forced into the position of getting all of its MPs to sign up to the Constitutional Convention’s Claim of Right (3) document which, unbeknown to most of the signatories, overtly asserted the right of the Scottish people to self-determination. Only one Scottish Labour MP refused to sign: Tam Dalyell, long-time opponent of devolution and poser of the infamous ‘West Lothian Question’. Others openly winced when the political implications of what they had signed up to were pointed out to them, but by then self-government was the cornerstone of Labour’s political agenda for Scotland, and with the eventual electoral victory in 1997, it was surprisingly quickly and comprehensively delivered.

The idea of establishing a Constitutional Convention was laid out in some detail in an article by James Wilkie, (4) a retired Scots diplomat living in Vienna. It was then followed through, further developed and refined by another ex-UK civil servant, Jim Ross, (5) previously an Under-Secretary at the Scottish Office who between 1975 and 1979 worked on the Devolution Bill. This idea was then picked up by what was the small and then still struggling Campaign for a Scottish Assembly (CSA), among whose ranks were members of the Radical Scotland collective, including Graeme Purves and the editor Alan Lawson.

The basic idea was that civic Scotland, in the broadest sense, in conjunction with its elected politicians, should sit down and thrash out the blueprint for a Scottish Parliament. This would then be presented as a fait accompli to the incoming Labour government to enact, thus minimising any delays in policy implementation. The merit of this approach was that most of the thinking, discussing and arguing would have concluded, thus aiding the actual legislative drafting process as well as ensuring that the finalised constitutional package secured broad cross-party consensus and popular approval.

The eventual Constitutional Convention brought together a very broad spectrum of civic Scotland, including the Scottish Trades Union Congress and Scottish churches along with the Labour Party, the Liberal Democrats and the Scottish Ecology Party. The SNP, true to their fundamentalism, stood aloof; or if you accept their argument, were cut out, because the option of independence was to play no part in the Convention’s deliberations.

Following the 1987 General Election, Labour found itself on weak ground, given their inability to deal with the ‘Doomsday Scenario’. So they needed to be seen to be far more supportive of a Scottish Parliament, which is why they agreed to join the Constitutional Convention and get their 50 newly-elected MPs to sign the ‘Claim of Right’. Not only did agreeing to participate give them something tangible in regard to self-government, it also had the advantage of allowing participation in a broader, more inclusive debate on the issue, while not needing to get itself tied down to one course of action or another. Participating in the Convention also offered an unexpected political dividend, given the Nationalists’ decision to effectively marginalise themselves.

It should be acknowledged that, when the creation of a Scottish Parliament finally became reality more than a decade later, the Labour Party did not accept the Constitutional Convention’s proposals in their entirety. Rather, they ‘cherry picked’ elements that were attractive to them. So while the Constitutional Convention engaged in impressive debates over how best to represent the electorate, what eventually emerged proved a lot less radical. Certainly, ‘first past the post’ elections were dropped in favour of a somewhat peculiar form of proportional representation, explicitly designed to deny any one party an outright majority, that party being the SNP. Further, the desire on the part of the Convention to ensure gender equality was strongly resisted, (6) though these debates did result in a sea change within individual political party thinking. Subsequent legislation was to set in place a requirement for gender audits for all Scottish Parliament legislation.

So the idea that the Convention provided a workable blueprint for the Parliament is to some degree mere fiction. The Convention’s scheme was deemed limited when it came to actually drafting the legislation, given that so much of its ambition was considered by those tasked with that endeavour to be vague and on occasions unclear. That said, those very same people were in no doubt that they had to come up with a workable devolution scheme, and deliver on it quickly. The Bill establishing the Parliament was the work of Scottish civil servants, reporting directly to Donald Dewar, then Secretary of State for Scotland, and influenced by his political advisor, Wendy Alexander.

The Constitutional Convention’s core purpose and undoubted achievement was ensuring a broad civil consensus around to the need for the Parliament, while also setting down the core functions that should be devolved to it, thus creating the expectation that a Parliament would be created, and an understanding of what exactly it would deliver. Arguably, therefore, the Convention’s prime achievement was less in determining the final details of the actual devolution scheme, and more about cementing Labour’s commitment towards the project itself.

When it came to campaigning in the 1997 referendum to create the Parliament, the SNP eventually fell in line, as they had no other option, and then worked hard to achieve the landslide ‘Yes/Yes’ result. Again, because of the work of the Convention, there was a broad-based coalition supporting a ‘Yes’ vote, (7) with only the beleaguered Conservatives propping up the ‘No’ camp. Labour opponents such as Tam Dalyell and Brian Wilson blended into the background, resulting in the ‘No’ campaign being seen as almost exclusively Tory, something Radical Scotland can take some credit for. The need to work across party political boundaries had been a core tenet of the magazine’s modus operandi, so it was fitting that a similar construct helped deliver Scotland’s Parliament at both a political and practical level.

The success of this strategy overall was such that even with the overwhelming majority secured by Labour in the 1997 General Election, and much as Tony Blair and others might have liked to have ditched, or at least watered down, the commitment to establishing a Parliament, the promise of self-government had to be delivered. Whatever his motive may have been, Blair’s insistence on another referendum gave the country the opportunity to make-up for the mistake of 1979. The referendum’s second vote, on the Parliament having meagre tax varying powers, was supposedly needed to preserve Blair’s commitment not to raise taxes when in office, thus avoiding Labour being characterised as the ‘tax and spend’ party. But for most self-government activists this second vote seemed tantamount to betrayal. That said, the Constitutional Convention had held few fiscal debates and the bold ideas proffered when they did were never followed through. Sadly, that fear of levying ‘Tartan Taxes’ still hangs heavy over the Parliament more than two decades later.

The other success of Radical Scotland that is worthy of note was that it showed that a different approach to the government of Scotland was possible, and that with a Parliament in place a range of new policy approaches could be considered, developed and then pursued. As noted above, a broad range of topics was discussed and debated in the magazine, and from these a few have been taken forward. Many such reforms were long overdue, but unable to secure Parliamentary time under the previous constitutional arrangements.

When Radical Scotland was wound-up in 1991, the land reform baton was passed to other publications, including Reforesting Scotland. Crucially, community land reform as well as the abolition of feudal land ownership, were both addressed in the very first session of the new Scottish Parliament in 1999, the latter being very much a personal ambition for Dewar. Some of the debates around educational reform and women’s rights later found a place in the Parliament’s legislative programme. There was also a move to better understand and address deprivation through prioritising a variety of social funding initiatives within poor neighbourhoods. In the event, however, the resulting Social Inclusion Partnerships proved less than successful. The same could be said for council housing reform. Labour offered the carrot of cancelling council housing capital debt, but oddly for them politically, only if direct council control was relinquished and housing associations took over ownership. The massive Glasgow housing stock transfer, another Dewar project, happened in this manner, and a few smaller authorities followed suit. However, other cities such as Edinburgh and Stirling had similar proposals decisively rejected by tenants. Abolition of the Thatcherite ‘Right-to-Buy’ council housing also occurred, but that took considerably longer. By allowing this reform to pass, new housing could be provided by both councils and housing associations, without the threat of its subsequent discounted sale to tenants. Further, a major programme of housing reform emerged from the work of the Housing Improvement Task Force, and that has been the basis of so much housing reform since its report’s publication back in 2002, (8) no matter the party in power.

All of Radical Scotland’s activity was conducted on the proverbial shoestring. The venture was entirely voluntary, in that no one earned a penny from it, so it was an entirely amateur production. That said, given its political ambitions, Radical Scotland needed to appear as ‘professional’ as we could make it, mirroring any magazine that one would find on the current affairs section of a newsagent’s shelves. Judged by the high production qualities of today, Radical Scotland looks both dated and amateurish, but such a comparison is misplaced. To us it appeared professional by the standards of that time. It was generally well written and properly edited, so for the most part the contents were challenging, different and hopefully exciting, especially when compared to the drab, wordy efforts of others. Marxism Today to some extent acted as our benchmark and interestingly, they wrongly assumed that we, like them, had our own offices and full-time staff. If only! Our reality was meeting up in Edinburgh University premises, on four Friday nights, in between each bi-monthly issue.

It is also important to remember that the magazine was produced prior to the advent of personal computing and IT networks. Therefore all copy had to be typed and delivered on time. That then had to be professionally typeset on to bromide sheets which, in turn, were cut up into strips and stuck down by hand, before these ‘originals’ were personally delivered to the printer, who set about making the printing plates to finally produce the required copies of the magazine.

Editing and layout involved scalpels, steel rulers, SprayMount and Tippex, and took up a whole weekend every two months for the collective’s entire membership. All titling, except for the main banners, was set down using Letraset. Covers were hand drawn on at least three separate sheets of tracing paper, to accommodate the three-colour printing process, given that full colour was beyond our financial means. The nature of this production method meant no one was ever quite sure what the final cover would actually look like, this only being revealed when the printer delivered the copies. Overall, magazine production was something of a craft operation, and we were very much apprentice journeymen. Today’s technology would have made all these tasks much simpler, and by the end of its life the magazine had started to dabble with computers, benefitting from the editor’s highly accomplished skills. It was just that the rest of us completely failed to understand or appreciate the possibilities.

We never attempted to be a mass circulation magazine, though we sought to convey that impression by ensuring that Radical Scotland was on sale in prominent Glasgow and Edinburgh news-stands, as well as in Waverley, Queen Street and Glasgow Central railway stations. To do that, we first had to generate an apparent demand by personally asking for the magazine in these various outlets, as a means to encourage them to order copies. Then we had to ‘sup with the devil’ and ensure that John Menzies, the monopoly newspaper distributer, would actually supply them. The problem here was that any unsold copies were returned months later, minus their covers so that they could not be resold.

The circulation of Radical Scotland never exceeded 2,000 copies, with a subscription base of some 600. While the members of the editorial board would attend all party conferences, except the Conservatives, and other major political events in order to sell the magazine, this was more part of our effort to get the publication recognised, rather than an attempt to increase its circulation. The readership was almost entirely politically active, or at least politically interested, so we did achieve very deep penetration into Scotland’s political community.

There was, however, a persistent debate within the editorial board about whether or not we should aim to secure more sales, and just how high that circulation could be. At the time, some collective members thought we should aim for 5,000 sales per issue, but now looking back, this would have been quite impossible without some other source of funding. Advertising revenue never exceeded £200 per issue, and a good number of these adverts were carried free on a reciprocal basis – you carry an advert for us and we’ll do the same for you. No-one was going to invest in a Scottish left-wing political magazine then, any more than now. But by being as professional as we could, and having a profile, then people might just think we had such backing.

Our most obvious failing was Radical Scotland’s inability to survive. There is, in relation to the magazine’s ultimate demise, some disagreement between us. One view is that it effectively died in 1987, following the General Election, because from then on, the political focus had changed. Immediately prior to the General Election it was clear Labour was going to hold together, so the only way to ensure self-government was via a Labour UK General Election victory. Both the first editor Kevin Dunion, and his successor Alan Lawson, gradually moved their political allegiance away from the SNP towards Labour. Thus criticism of the Labour Party was toned down to ensure that it stayed committed to delivering a Parliament. This caused the magazine to lose its edge and, significantly, its nationalist readership. Working with what was already a small readership base, this loss proved fatal, given that it was impossible to attract a new political readership to replace them.

It was also obvious to nationalist members of the collective that this changed political environment consigned Radical Scotland to becoming effectively the house magazine for the CSA and its Constitutional Convention project. Consequently, what was left of the magazine’s more overtly nationalist side was gradually diluted. Radical Scotland did struggle on for another four years, but for them it had lost its way. It tended increasingly towards mainstream respectability, rather than its early iconoclasm, and no one is really that interested in a worthy, but boring publication.

The alternative perspective is that the magazine took the correct decision to cease publication in 1991, as its original objectives had all but been met, and the mainstream media were not only now in favour of establishing a Parliament, but were also covering many of the issues the magazine had once championed. (9) That was perhaps a generous reading of the situation, but certainly Radical Scotland’s role was no longer critical in encouraging the self-government project. So it was now time to get on with the rest of our lives. Delivering a magazine was an all-consuming task and at a personal level, many of our lives had become more crowded and busy with family and work commitments, so losing most Friday nights and six entire weekends a year was increasingly hard to sustain.

It is sad the magazine did not survive to offer a radical critique of emergent Scottish governments and post-devolution politics. However, at the time there was no new generation of activists stepping up to take on this role. Over subsequent years a few more fringe political magazines appeared, but they almost as quickly folded.

More recently, in the internet era, a range of new Scottish political and cultural offerings has appeared, such as Bella Caledonia, Common Weal, Nutmeg, Sceptical Scot, Skotia, Scottish Review, Scottish Left Review, The Skinny and Wings over Scotland, as well as a mainstream newspaper offering, The National. Most of these publications emerged in the lead up to the Scottish independence referendum in 2014, feeding off the enthusiasm generated by the broad-based ‘Yes’ Campaign. However, the growing influence of social media has started to cause ghettoisation among their readership: small groups of like-minded people speaking primarily to each other. Given this changed world, none of these offerings can really replicate what a political magazine was in that pre-internet age.

Radical Scotland’s legacy, to our minds, is fourfold. Firstly, its key achievement was that the magazine played a part, and we would contend an important part, in changing the political climate and, crucially, promoting the key mechanism which ensured that Labour felt obliged to deliver on self-government when it eventually won a UK General Election. It both contributed to, but also reflected, the emerging broad political consensus on self-government. Radical Scotland both stimulated and then rode that mood change, while simultaneously helping to keep the mood alive and kicking. The magazine was there in the dark days between 1981 and 1987 keeping the self-government torch glowing, after it had almost been extinguished in what remained of Scottish politics. Jack Brand, the founder of the CSA, was clear that after 1979 that the most important thing was simply to keep the ‘flame alive’, and especially within the Labour Party. (10) He saw the CSA as being a vehicle for that project, so given the close ties Radical Scotland had with the CSA, it played a key role in undertaking this exercise too. It is easy to forget just how much devolution dipped in significance as an issue from 1979 to 1983, and even through to 1987.

Radical Scotland was also important in keeping self-government alive for what was then termed the ‘broad left.’ It created the critical forum for debate and in so doing linked together a diverse range of political activists across the country who could then coalesce around an agreed route forward. The coining of the ‘Doomsday Scenario’ ably depicted the reality of Scotland’s political position at that time, trapped within linked democratic and constitutional deficits. Being unable to address this reality put Labour on the back foot, and so forced it to reappraise its constitutional positioning.

Secondly, after the 1987 General Election, there was an agreed means to plan for the establishment of the Parliament, and again the magazine can take some credit for this. Labour’s involvement bought them breathing space and provided the opportunity to think through the construction of a Parliament with other interested parties. Despite the continuation of the ‘Doomsday Scenario’ following the 1992 General Election, Labour’s commitment to delivering self-government was all but sealed through its active participation in the Constitutional Convention.

Thirdly, Radical Scotland provided a tangible example of the value inherent in seeking to build bridges in politics, something that also proved crucial to actually delivering the Parliament. It showed that political issues and the reform agenda were not the preserve of one single political party, but needed to generate broad support in order to take matters forward. In that respect the magazine was able to link and allow a wide range of individuals and groups to engage in re-thinking our situation and come together as a wider social movement which sought to secure change. For Scotland’s political future this is a lesson that should not be forgotten. During the 2014 independence referendum it quickly became clear that the ‘Yes’ campaign was far more than the SNP, something the SNP did not quite appreciate then, nor perhaps fully understands even today. The Parliament’s current make-up, which partly reflects the compromised nature of the electoral system and, post-2014, the polarised narrowing of party politics, is deeply unhelpful in allowing the further development of this notion of consensus ‘broad left’ politics.

Finally, for a short period Radical Scotland was able to align the ambitions of self-government with an overtly anti-Conservative agenda. The failure was that this did not follow through to the next step: making self-government properly left-wing, and a progressive force, has certainly not yet happened. In the 1980s, radicalism seemed so easy to achieve: you merely articulated your outright opposition to Thatcher. But the world now finds itself in a very different place, with both the Labour Party and the SNP effectively embracing so much of her legacy. It would also be true to say that the magazine neither adequately realised, nor properly acknowledged that the Labour Party in Scotland is a deeply conservative institution, as its obvious lack of policy ideas and ambition when in government exposed. Once the original backlog of reform projects was worked through, their policy cupboard was bare, and Jack McConnell’s administration’s policy mantra of “doing less better” proved to be Labour’s death knell. That exact same criticism equally applies to their political successors, the SNP. While they happily espouse the rhetoric of social justice and community control, their actions reveal a centralising, pro-business, neo-liberal approach, happy to sub-contract policy development to ever-willing paid lobbyists.

Radical Scotland set high hopes for a ‘radical’ Scotland, but there has long been a self-imposed limit on just how radical this Parliament chooses to be. But then, the Parliament is merely a reflection of Scotland as it currently finds itself. So perhaps our biggest error was to exaggerate just how ‘radical’ Scotland actually is.

(1) Both authors acknowledge the helpful comments on what was originally a conference paper from other collective members, namely Chris Cunningham, James Robertson and Graeme Purves. Further observations from James Mitchell, Lindsay Paterson and Scott Hames helped refine the wider context. Thanks also to Bill Dunlop for editing the original longer draft.

(2) Radical Scotland ‘Hoping for the best … preparing for the worst’, Radical Scotland. February/March 1986, 25, pp. 9-11.

(3) Robert Grieve, ‘A Claim of Right for Scotland’, Radical Scotland. August/September 1987, 34 pp. 17-20.

(4) (James Wilkie, ‘A Scottish Constitutional Convention: the door to the future’ Radical Scotland. December/January 1984, 8, pp. 16-178.

(5) Jim Ross, ‘The constitution-mongers have a case’, Radical Scotland. August/September 1987, 28, pp 15-17. Jim Ross, ‘Grasping the Doomsday Nettle – methodically’, Radical Scotland. December/January 1988, 28, pp. 6-7.

(6) Isobel Lindsay, ‘PR and the female deficit – a compromise’, Radical Scotland. February/March 1989, 37, pp. 15-16.

(7) The Scottish devolution referendum was a pre-legislative referendum held on 11 September 1997. Two question were asked, firstly, whether there was support for the creation of a Scottish Parliament, and whether the Parliament should have tax-varying powers. The result was 74.3% in support of establishing a Parliament, and 63.5% in favour of the Parliament having tax varying powers. Turnout was 60.4%.

(8) Housing Improvement Task Force, Report of Housing Improvement Task Force, Edinburgh, Scottish Executive, 2002.

(9) Alan Lawson, ‘Time to bow out?’, Radical Scotland, June/July 1991, 51, pp. 8-9.

(10) James Mitchell, Strategies for Self-Government: The campaigns for a Scottish Parliament. Edinburgh 2006.

The last time Margret Thatcher was PM was 1990, a dedade into the previous century. She died 10 years ago, as did people making blogposts about her.

This article is clearly a review of Radical Scotland during Mrs Thatcher’s reign and beyond so it would be very difficult to write it without actually mentioning her. I was relatively unaware of this movement during this time as I was not particularly politically aware in 70’s & 80’s and found it an interesting article.

Or are you saying that people should not write articles about this period of time? Commentators of all political perspectives agree that Mrs Thatcher’s time in office was historically significant for this country and we are still living with the impact of her government’s policies whether we agreed with them or not.

In other words I don’t understand why you have posted this bizarre comment?

Just so. And it’s timely given the major ‘Break Up of Britain’ event this weekend.

Graeme – having lived in Scotland through period between 1979 – 1997 I think Margaret Thatcher and her government’s policies were a major factor in building support for devolution. It would perhaps be more appropriate to have a statue of Mrs Thatcher outside Holyrood to acknowledge this fact?

Ah this is good. Proper left wing stuff. Something I can respect. Not the pseudo-socialist Neo-Marxist post-modernist nonsense that passes for progressive today. Regressive more like.

Then, the white working classes were seen as allies not as “problematic”.

Going to University then would be a liberating experience with free speech a critical part of that liberation. Whereas today, diversity means narrow thinking and interpretation.; inclusion means not saying what you think because it makes the member of a minority “unsafe” and offends, and Equity is simply blatant discrimination against the majority dressed up as social justice.

It was when independence was seen as setting the stage for a completely socialist Scotland. Although, it didn’t really cover the fact that there would be people who were nationalist rather than socialist.

What do you have now? Humza and his merry band of self-serving numpties. Good luck on that one.

Hi SteveH, I am proud to say I was a distributor in a small way of Radical Scotland and still have many copies in my Loft. I just wanted to say to you I am a Scottish Nationalist and a Socialist and not all M.S.Ps are numpties any more that those of all Parties at Westminster. Have a good day.

and Kind Regards.

Yes, indeed, all the Westminster mainstream parties are complete numpties too.

However, I think the SNP have let badly let down their independence supporters. They take their support for granted, and allow ideological inclinations to blind them to what’s really important. Of course, the cynical SMP MSP’s also supported such views they thought would win them support, regardless of whether they believed the ideas or not.

I just hope this isn’t the death knell of democracy.

I respect genuine beliefs, even ifvI don’t agree with them.

Cheers, here’s to times gone by, when you knew who your friends, or your enemies were.

Having read this and the previous part of the story, I think this is a comprehensive and fair appraisal of what Radical Scotland the magazine was, what it set out to do, what it achieved, where it was weak and what its strengths were. Douglas and Jim acknowledge the tensions and divisions within the team as well as the shared ambitions and tensions.

I was a late arrival to the editorial board – I think I joined in late 1985, but possibly it was 1986 – but stayed on until the magazine closed in 1991. Having chatted with Douglas and Graeme Purves at yesterday’s Break-up of Britain conference honouring Tom Nairn, it’s clear that there is unfinished business. But that was always going to be the case, and it is reasonable to say that all that unpaid labour and concentrated thinking and writing we put in in the pre-internet era made a difference. The 1980s was the decade of Thatcherite revolution and we are still living with the consequences of that revolution. But it was also the decade of an awakening Scottish political and cultural self-awareness, a rediscovery of what we either never knew or had forgotten about ourselves and this country, and a growing belief that we could be better, whether through devolution or (for many of us) eventually through independence. Again, unfinished business.

Bad as the last 13 years of Tory rule have been, they would have been much, much worse had Scotland not had its Parliament, firmly embedded for more than a decade, as a bulwark. Radical Scotland played a part in bringing about the devolution settlement, and moving the debate on to one about independence. The obvious failings of Ukania that Tom Nairn wrote about over several decades haven’t gone away, but they have become more critical. It is within that context of the UK’s dissolution, especially after Brexit, that the next stage of Scotland’s political story will unfold.

Sorry, end of first paragraph in post above should read ‘shared ambitions and successes’.

Thanks James

Thanks James. Much appreciated.