Redcoat Restaurants, the chain and Tartan Microscopes

Some people have attacked those who argued that naming a restaurant in Scotland’s foremost visitor attraction after the Redcoats was a sign of their terrible racism, their immaturity or their dire and virulent nationalism. But actually what’s being exposed in this exchange is something quite different.

Writing in the Scotsman poor Euan McColm is having a fit (‘Edinburgh Castle Redcoat Cafe row is another sign of SNP’s problematic nationalism’). He fumes: “Scottish nationalism is supposed to be positive, to be about big ideas for progress. Its leading figures tell us their special “civic” nationalism isn’t about grievance but about unleashing the potential of a confident Scotland. But all nationalisms – “civic” or otherwise – require an ‘other’ and, as countless independence supporters have confirmed – that other is England. Of course it is.”

He says: “Whisper it – there have been Scottish Redcoats, you know?”

Well, of course, quite right, but as I pointed out on Twitter: (my) objection to the Redcoats isn’t based on their nationality, it’s based on their actions.

The frothing incomprehension of the Unionist Commentariat starts from two principle assumptions 1) everything’s fine 2) if you question anything you must be a Mad Nat. This twin approach Question Nothing and Despise Anyone Who Wants to Run their Own Country, makes them look quite crazy quite often.

Over at The Telegraph someone called Robert Tombs writes a classic of the genre (‘The SNP can’t handle that Scots were the real ‘oppressors’).

“Redcoats have not been universally popular” he explains solemnly.

“This long and dishonourable British tradition of undervaluing “uniforms that guard you while you sleep” (Kipling again) sadly persists. And now some Scottish nationalists are joining in. In their resentment of all that is British, they are willing to rubbish their own patriotic heritage. That’s the difference between patriotism and nationalism. Nationalism is discontented with its own country and wants to make it something else.”

Are you following?

Robert goes on: “The latest triviality – nothing is too small to be grist to the resentment mill – is insisting that the Redcoat Café, in Edinburgh Castle, should be renamed.”

Jumping history he ends with a triumphant flourish: “The Scots were much keener on Union than the English, and many of the greatest Scottish names were vocal unionists. I suppose that’s hard for today’s nationalists to swallow.”

I mean, sure Robert.

Tartan Microscopes

Meanwhile over at the Scottish Daily Express, their editor Ben Borland is going completely nuts over the issue (‘History lesson for ignorant Nats… many brave Scots served as Redcoats, including some of our greatest war heroes!’). Borland rants: “The furore over the Redcoat Cafe has got me riled up as hysterical politicians and other 90-minute patriots are falling over themselves to tarnish the memory of all those Scottish military heroes who fought in the famous scarlet tunic!”

“The furore over the refurbished Redcoat Cafe at Edinburgh Castle is one of the most pathetic and embarrassing spectacles I’ve ever had the misfortune to witness. There really is something very wrong with Scottish education if so many ignorant nationalists don’t realise that Scots served as Redcoats.”

He continues, perhaps not making the great argument he thinks: “Although the red tunic was first adopted by English forces in the 16th century, the uniform only really came into its own along with the Empire itself after the Act of Union in 1707.”

Back over at The Scotsman Alison Campsie (‘Edinburgh Castle Redcoat Cafe and a row that obscures Scotland’s long history of the scarlet tunic’) is given the job to explain some of the history to the papers readers. She writes: “The term ‘redcoats’ becomes loaded with sensitivities when looking at events after Culloden when the British Army advanced across the Highlands to first rid it of Jacobite supporters and then destroy its culture at large. The Duke of Cumberland, as early as February 1746, was talking of “speedy punishments”, while General Humphrey Bland, an Irishman, wanted “ridd of all chiefs of clans” and their “barbarous language”.

She goes on: “Highlanders faced killings, rapes and burning of homes and crops in the immediate aftermath of the battle.”

“At work were figures such as Captain Caroline Frederick Scott, an Edinburgh soldier who relished his own notoriety. As Scott toured around the Hebrides looking for the defeated Jacobite leader, he landed on various islands and ordered his men to plunder livestock and carry out the most atrocious offences. Scott’s men reportedly raped a blind woman on Rona before targeting two girls on Raasay.”

Meanwhile, Captain John Fergusson, of Aberdeenshire, became notorious for his abuse of prisoners.”

I mean, the bulk of her piece is to explain that other bits of the army wore red ‘tunics’, as if this is somehow remotely interesting or to the point. At least she includes some detail of the atrocities but then its even weirder because she ends writing: “According to historian Professor Tom Devine, many thousands of Highland and Lowland Scots were recruited into the British Army from the Seven Years War (1753-63) and fought in their red tunics throughout the empire until the uniforms changed in the later part of the 19th century.”

“Numerous paintings from the time depict both officers and men of the famous Highland regiments wearing the familiar red tunics together with kilts from the waist,” he said.

I sometimes wonder why they made themselves such standout targets. Anyone who’s done mountain walking and worn red socks/ jackets know that helps them to be spotted

The use of red coats dates back to the Tudor period, when the Yeomen of the Guard and the Yeomen Warders were both equipped in the royal colours of the House of Tudor, which were red and gold.

The term first became a synecdoche for the soldiers themselves during the Tudor reconquest of Ireland in the 16th century.

Up to a certain point being able to be identified by your own side was important until firepower made distance between attacking sides more important

Yep; the red coats proved to be a liability, especially when, during the First Boer War, British soldiers were for the first time faced by ‘snipers’: enemies armed with rifles that fired the new smokeless cartridges. They were replaced by khaki uniforms in the early 1900s.

@Cathie Lloyd, one motive would be terror. Only a tiny part of a soldier’s job would be on a battlefield, if that. The British Empire had to work on terror, as even with colonial recruitment its forces were spread very thinly across vast regions. This is why the British (and French) were such keen advocates of colonial air policing (which has had atrocious effects ever since). The garrisons, the raids, the matches, the parades, the punitive expeditions, the policing, the presence at executions, the guards on official buildings, the massacres: all these are branded and linked in the colonial populace’s minds.

Something similar happens after violent and aggressive targeted policing in the UK today, where some children, protesters and activists develop a similar terror of police uniform.

Of course, British authorities recognised this, but reversed it, claiming that tartan was the insignia of terrorism.

No, the reason definitely had to do with tradition rather than terrorism; as I said, the use of red coats dates back to the Tudor period, when the Yeomen of the Guard and the Yeomen Warders were both equipped in the royal colours of the House of Tudor, which were red and gold.

Loads of armies, all over Europe and its colonies, wore red coats, the reason being that red was a popular royal livery.

On British military terror in India, in Colonial Justice in British India: White Violence and the Rule of Law, Elizabeth Kolsky quotes George Curzon, Viceroy of India, in a letter to the Secretary of State in 1904 (on p199):

“You can scarcely imagine what a terror the British soldier has made himself to natives, both in the neighbourhoods of cantonments and on the march, in the main by his drunkenness and lust. Most of the rows take place when a soldier has had too much and four or five have a woman in the background. The result is that, in many places, the inhabitants of a village flee at the approach of British soldiers.”

And that is just the terror of unofficial (or perhaps semi-official) variety.

Where terror is deliberately employed, helpful traditions will tend to be kept (again, vitally important for association to work psychologically), and unhelpful ones amended or discarded, much like military technology and tactics.

‘Drunkenness and lust’; nae mention of those scary red coats. Face it: British soldiers wore red coats simply because that was at one time the royal livery; there’s no need to postulate any ulterior motive to explain it.

(This isn’t to say that the British Empire didn’t use terror as a instrument of policing; it’s only to say that this has nothing to do with why British soldiers wore red coats back in the day.)

@Cathie Lloyd, plus of course, making ordinary soldiers more visible can make officers less so. As Charles Callwell pointed out in Small Wars: Their Principles and Practice, if British officers stood out in dress and appearance from other ranks, especially in colonial regiments, it makes them easy targets for snipers. I mean, cannon fodder, right? So “both officers and men of the famous Highland regiments wearing the familiar red tunics” is basically creating human shields for the officer class.

Sniping wasn’t technologically possible until the Boer Wars, at which point the British army did ditch its red coats for khaki.

Officers (in the days when they led their men in the field) also wore red coats, often sat on horses, and marked their location by flying regimental colours. The last British Army regiment to carry its regimental colours into battle was the 58th (Rutlandshire) Regiment of Foot in January 1881 at the Battle of Laing’s Nek during the First Boer War – again because the practice made commanders vulnerable to sniper fire.

The ancient Romans had sniping weapons, and some medieval crossbows were effective and accurate over range (particularly if the operator was shielded and stabilised), snipers played a significant role in the USAmerican Civil War, but military writers like Callwell were concerned with ambushes and guerilla tactics which meant that officers could be picked off at closer range than on open battlefields of the time, with much less reliance on technologically-advanced weaponry. If, of course, you could readily identify an officer.

Yeah, well… sniping isn’t the same as either ambuscado or guerilla warfare.

Sniping (deploying marksmen to engage targets from distances exceeding the target’s detection capabilities) didn’t become a military tactic until the invention of breech-loading rifled guns with magazines and smokeless powder. These first became available during the Boer War; the British were equipped with the Lee–Metford rifle, while the Boers had Mauser rifles from Germany. The tactic of sniping was first developed by the Boers, and it was the devastation caused by this tactic that led to the British army to replace its traditional red coats with khaki and to end the traditional practice of using standards to mark the location of their battle commanders.

The first British sniper unit began life as the Lovat Scouts, a Highland regiment, formed in 1899. They were among the first to British soldiers to lose the traditional red coats; they fought in ghillie suits to avoid detection.

We got told about the Battles of Saratoga of 1777 (Revolutionary War between British Empire and nascent United States of America) in history class in school, where we learnt something similar to Wikipedia’s take:

“Morgan placed marksmen at strategic positions, who then picked off virtually every officer in the advance company.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battles_of_Saratoga#Battle

The early rifles used were apparently based on the Jäger types brought by German immigrants which German light infantry had been using. Being muzzle-loaded, slower and more cumbersome than smoothbore muskets, their range and accuracy giving their only benefit: sniping (‘marksman’ is unnecessarily gendered in general usage). Artillery soldiers were reportedly also targeted by snipers in those conflicts, maybe others like messengers, I don’t know.

So, the wearing of red coats by British combat troops seems to have outlasted this significant engagement by at least a century. But they did create their own light infantry, armed with rifles, and some of those wore green, it seems. Like Robin Hood’s merry men. In Sherwood Forest. Suggesting that camouflage was a pretty well-understood concept.

Anyway, as Callwell writes, in wars where the British moved through dense undergrowth, like the Ashanti and Māori Wars, British officers were picked off at a high rate at short range by “hostile marksmen”.

The UnionBot2000 still struggles to integrate information from multiple sources and the real world, I see.

“In January 1800, the British Army formed a corps of 40 officers and men to experiment with the use of the newly developed Baker rifle.”

“An early adopter of camouflage, its troops wore green jackets instead of redcoats. They were also taught to operate in pairs on their own initiative rather than in line formation under strict orders.”

“The regiment spent its early years heavily engaged in northern Europe. It sent a detachment to serve as sharpshooters on Admiral Nelson’s ships at the First Battle of Copenhagen in April 1801.”

https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/rifle-brigade-prince-consorts-own

Sharpshooter is a genderless equivalent of marksman, and both apply to injurious and non-injurious targeting. For example, I knew a medal-winning female sharpshooter who as far as I know never shot at anyone (she shot at Bisley, though). Sniping, however, descends from hunting, and was apparently in local use before these early ‘Green Jackets’ were formed, and became a recognised military term long before it became popularised. Therefore ‘sniper’ is the appropriate and accepted English term for the role I’ve been discussing (in other languages the role might be the equivalent of ‘hunter’).

It was interesting to read a summary of a USAmerican report on police sniping, which although does usually involve shorter shooting distances than military snipers, it says, does attempt to dispel some of the myths about sniping. If the information is accurate, the lower range could be contained within a single room. This is reminiscent of how much sniping was done in the house-to-house battles in WW2, also snipers in trees or on rooftops. With concealment or cover, angle outside the target’s vision (from above, say), environmental effects like night and rain, snipers can work like hunters and shoot from close range with the element of surprise. Which helps accuracy, particularly if you need a kill shot or want to avoid hitting something near the target (like a hostage in police situations, but there are other things militaries might want to avoid hitting).

@Lord Parakeet the Cacophonist, if you keep plagiarising without reference, I would consider that not only foul play, at a comments-banning level, but an indication of how cheap, shoddy, vacuous and immoral British Unionist arguments tend to be, even as they pretend to be any sort of military historian on their wrong side of culture wars.

You can call picking off targets at short range ‘sniping’ if you like; it doesn’t change the fact that the British army replaced its traditional red coats with khaki (and stopped marking the location of its commanders in the field with regimental colour standards) in response to the effectiveness of the Boers’ tactic of deploying marksmen to engage targets from distances exceeding the target’s detection capabilities, a tactic which was first made possible by the invention of breech-loading rifled guns (like the Mauser and Lee-Metford) with magazines and smokeless powder. Lord Lovat’s men, in their ghillie suits, called the tactic ‘sniping’ because they likened it to hunting snipe on the estates back home.

You will, of course, be aware that Charles Callwell published his manual on counterinsurgency strategy (‘small wars’) in 1896, prior to the Second Boer War, largely in response to his experiences of fighting irregular forces in Central Asia, South Africa, and the Middle East in the last quarter of the 19th century, and that he doesn’t actually use the word or refer to the specific tactic of ‘sniping’ in his comparisons with previous insurgencies – precisely because that tactic, of deploying marksmen to engage targets from distances exceeding the target’s detection capabilities, wasn’t possible in those previous insurgencies, prior to the invention of breech-loading rifled guns (like the Mauser and Lee-Metford) with magazines and smokeless powder.

I could not believe that Empire: Total War was inaccurate, and this diagram backs up the typical colour schemes in its line infantry uniforms:

Military uniforms, 1690–1865

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Encyclopaedia-Britannica-1911-27-0611.jpg

Well, if you believe the Encyclopaedia Britannica, apparently, although they seem to be confused about the concept of ‘England’. Oh well. I particularly enjoyed the caption: “England: Scots Fusilier Guards, Officer, 1865”.

Not much call for an away strip, on that evidence.

Yep; that’s just the kind of category mistake that encourages nationalists to misassociate red coats with English oppression. Of course, this misassociation masks the real oppression in our current establishment: that which is implicit in the private ownership of the means of production, which transcends nationality.

Of course the really significant point about the historical use of state terror by the British Empire, which became associated with the appearance of red-coated soldiers, is that it isn’t just historical: it continues today. Although today subserviently to the USAmerican Empire (top in the “special relationship”), conveniently enabled by the British quasi-Constitution which allows most foreign and military policy to be conducted via royal prerogative:

“A little known but long standing nuclear weapons agreement between Washington and London is up for renewal – and must be challenged.”

https://www.declassifieduk.org/mps-must-oppose-us-uk-nuclear-arms-accord/

Terror that evolved through the use of gunboats and armoured cars (surely the genesis of the Daleks) through bombers and nukes to drones and new-generation weapons. Should the United Nations be inclined to adopt ‘state terrorism’ as an indictable crime (which might be pushed by Ukraine among others), we might see the Brits in the ICJ dock sometime. That is, instead of normalising terror, we might choose to abnormalise, pathologise and condemn it.

Our current establishment (the whole matrix of official and social relations within which power is exercised in this country) undoubtedly involves the use of the state apparatus to conduct acts of terrorism against its own citizens in order to maintain itself; e.g. by threatening us with the various demographic, economic, political, and social catastrophes that it claims would befall us if we didn’t consent to its continuation and/or we tried to change it. This is in line with the definition of terrorism agreed by the UN, which is any action that aims ‘to create a general climate of fear in a population and thereby to bring about a particular political objective.’

A major function of critical theory as praxis (that is, as the free, universal, creative and self-creative activity through which we create and change our historical world and ourselves) is to expose such acts and to thereby weaken and subvert the establishment they maintain. That’s why no one who has a vested interest in the current establishment or ‘tradition’ likes it.

As I’ve said elsewhere, the existence and extent of prerogative powers is a matter of common law, making the courts the final arbiter of whether a particular type of prerogative power exists or not. Parliament may legislate to modify, abolish, or simply put on a statutory footing any particular prerogative power. Prerogative powers are abolished by clear words in statute or where the abolition is necessarily implied. The prerogative powers of government are, under the Westminster system, thus severely limited.

Those powers are further limited by three fundamental principles, which are:

1. The supremacy of statute law (Where there’s a conflict between the prerogative and statute, statute prevails).

2. Use of the prerogative remains subject to the common law duties of fairness and reason and is therefore subject to judicial review.

3. While the prerogative can be abolished or abrogated by statute, it can never be broadened.

The continued existence of prerogative powers (that is, the albeit it limited ability of ministers of the Crown to make some decisions that pertain to our public affairs independent of our parliaments) is deeply undemocratic. All prerogative powers should be put on a statutory footing.

They are nothing if not predictable. Twenty years at least now that independence has been a hot issue and drones like Farqhuarson are still solemnly lecturing us about ‘grievance’ and the evils of Nationalism. And the presence of Scots in red coats at Culloden was a big ‘gotcha’ for them at least 40 years ago. They never offer anything new to the public debate or to the understanding of independence or any of the relevant historical background. Among the biggest manpower contributions to British forces were those from India and Ireland but that did not invalidate independence in either case, while there is now a new understanding of the large scale of Scottish mobilisation for the Jacobites in 1745 and the importance in that of opposition to the Union.

They see it as a jolly good wheeze, a bit like Clarkson’s ‘H982 FKL’ car number plate in Argentina. Anyone who’d object to a ‘One Para’ restaurant in the Bogside or an IDFeed one in Palestine would be a “woke lefty” BUT Sellotape a paraglider to the back of your jacket and you’ll be up in court charged with terrorism.

Do they still have the redcoat storytellers, in period dress, at the Castle, demonstrating the operation of 18th century muskets and the like?

I don’t know why anyone should be surprised that the Castle features – and has always featured – military themes; it is, after all, a military museum, war memorial, and regimental headquarters.

If you find that kind of stuff offensive, surely you shouldn’t visit it.

Its not really about ‘Military themes’ is it? (!) It’s about the historic – uncontested – accounts of horrific what we call now war crimes.

But the accounts we have of what went on during and in the aftermath of the Jacobite risings – as well as the historical significance of those events – are deeply contested. What transpired during the period is one of the most controversial matters in Scottish and British historiography.

Anyway, it’s an almost 300 year old grievance, largely manufactured and completely romanticised and sentimentalised by the Edinburgh Tories a century after the events themselves. As you say yourself, there are much more pressing issues.

(And anyway: it’s 30 years since the Redcoat Cafe and the Jacobite Room opened at the Castle. Why are the nationalists only making an atavistic grievance of it now? Have they only just noticed?)

I don’t think the record of atrocities after Culloden are a matter of contest at all, they are recorded by their perpetrators as a matter of pride. The suppression required this. The ‘nationalists’ are not making a grievance of it, people are questioning why a statutory body thinks this is ok. They are quite right to do so. Questioning the way things are is a good thing, an essential thing. We should do more of it.

@Editor, indeed. These are all deliberate choices, after all.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2024/jan/27/company-renames-plantation-rum-after-criticism-over-slavery-link

We should indeed engage more in cultural criticism and question the various historical narratives we weave from the written records.

And, sure; the constitutional revolution and counter-revolution that took place in 17th and 18th century Britain was a bloody affair, which culminated in the sometimes brutal suppression of the counter-revolutionaries and their milieu by the state. That’s the nature of civil war, and it’s to be deplored.

But to make such a song and dance about alluding to ‘Redcoats’ and ‘Jacobites’ in a visitor attraction that featured in that conflict not only makes no sense, but also trivialises the whole matter in its pettiness.

@SD

The exploitation of slaves in the plantations of the Caribbean is hardly comparable to the suppression of counter-revolution in parts of Britain. The ‘risings’ in the Caribbean were by people seeking their liberty; the Jacobite ‘risings’ in Britain were by people who were trying to restore the tyranny of the ancien regime. Though the brutality with which those risings were suppressed is undoubtedly comparable.

Anyway, ‘The Redcoat Cafe’ is owned and operated (and named) by the private Benugo chain, not by Historic Environment Scotland. Maybe the nationalists’ atavistic grievance is with Benugo.

Edinburgh Castle is a British Garrison and the vast bulk of it visible from Princes St and Castle Terrace is from the era of Fort George. It was massive overkill in purely military terms even where the French might have been involved The huge Union flag it flies carries the same symbolic imperial message but much cosier nowadays – like the Monarchy and the Lords are just ‘symbolic’, and of course our very own BBC is a ‘Public Service’ broadcaster’. Symbols are important and the almost complete vanishing of the Union flag from Scotland over the last 30 years and its popular replacement with the Saltire tells you something that those who sneer at the (Scottish) ‘flag shaggers’ don’t want to hear.

Is the Saltire more visible than it was 30 years ago? Since its adoption as Scotland’s national flag by the Edinburgh Tories in the 19th century, it has officially been the correct flag for all private individuals and corporate bodies to fly, the royal standard or ‘Lion Rampant’ being reserved for use by the Crown. It has also, where possible, been flown from Scottish government buildings, both before and after devolution, every day from 8:00 am until sunset (with certain exceptions). It’s often flown alongside the union flag, in which it’s also incorporated. It’s also long been visible in the devices of Scottish businesses, civic societies, churches, military regiments, etc.

Symbols are important. The Saltire was adopted as Scotland’s national flag to symbolise Scotland as a ‘home nation’ within the union and to provide a totemic emblem around which British patriotic sentiment in Scotland could coalesce. It was filched from Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount’s 1542 Register of Scottish Arms, in which it’s first recorded as a heraldic flag, possibly based on the precedent of Queen Margaret’s use of a white saltire in the canton of a blue flag as a heraldic device in the late 15th century.

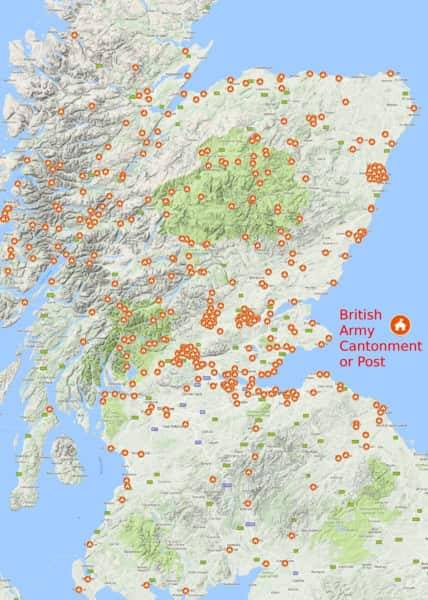

Gonna need a bigger map. Here’s an interesting piece:

“Between 1795 and 1807, estimates suggest 13,400 slaves were purchased for the West India Regiments.”

https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/slaves-red-coats-west-india-regiment

and I presume they were deployed against Jamaican Maroons.

Red coats were also worn by the British Colonial Auxiliary Forces and the British Indian Army (and feature in many blockbuster colonial-history Bollywood movies).

Loads of armies, all over Europe and its colonies, wore red coats. So what? Red was a popular royal livery.

Yes its their actions that horrified people then which in thoes days must have been seriously abhorrent and as for Scots happy with the union it seems to me that they were the very few that benefited from it….The people WHO HAD NO SAY were against it and there was much unrest for several years after….The ’45 was not about Scotland against England but effectively a religious one

The counter-insurgency tactics of the Hanoverian regime might not have been so ‘seriously abhorrent’ in those days. The level of violence with which the Jacobite rebellions were finally put down was par for the course in the constitutional struggle that manifested itself in the long civil war of the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries. The brutality of that civil war would have been ‘normal’ at the time; the abhorrence we ascribe to the historical players in our imagining of those times might well be anachronistic.

And Scotland benefited immensely from the Union in that it gave the failing Scottish economy at the time access to English colonial markets, from which we had previously been excluded. This enabled us to transform our subsistence agricultural economy into a profitable mercantile one and to accumulate from that trade the vast capital that subsequently fuelled the industrial revolution, by which we finally abolished scarcity. The Union also consolidated the political revolution that brought the ancien regime of absolute monarchy to an end in Scotland, the revolution that the Jacobites were seeking to reverse.

We should all be more grateful

We should all be more sceptical of our ‘given’ historical narratives.

I certainly am

Even in the case of the traditional ‘redcoats’ narrative?