Digging deep with Demarco

Richard Demarco has long been a prominent figure in the Scottish cultural sphere. He has been a significant cultural progenitor, raising the profile of the visual arts within Scotland. Demarco is well-known for his provocative statements, including fierce criticisms of Scotland’s cultural institutions and “officialdom”. He has, he admits “got up lots of people’s noses” through his thoughts and deeds.

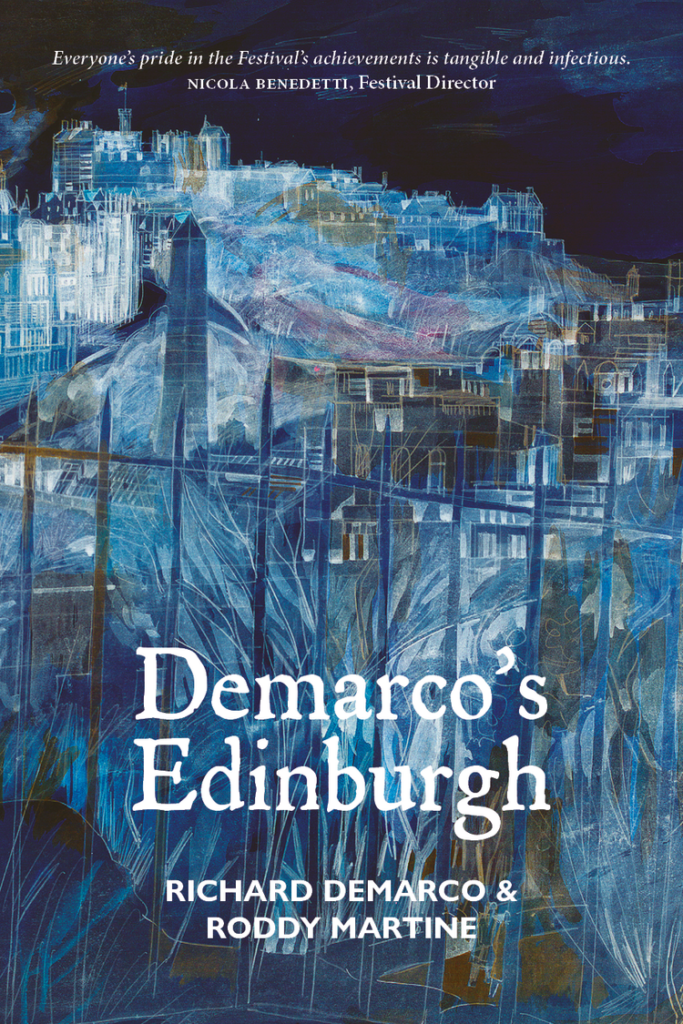

Above all, he is known for his view that the Edinburgh Festival and Fringe is a pale imitation, if not a perversion of, the original vision of a ‘flowering of the human spirit’ through the language of the arts. He admits that the book Demarco’s Edinburgh (Luath Press, 2023) could be seen as a cri de coeur for the Festival or even an obituary. The Festival has, in his view, been transformed from an event worthy of cultural pilgrimage to a “money making machine”, “a knees up”, “a circus”.

This aspect of Demarco is usually what predominates in his talks and public dialogues. This is what usually leads to headlines. Only by spending substantial time with him, does the deeper story emerge. As John Haldane has noted, there is a deeply spiritual quality to Demarco’s faith in art. Demarco’s is a story of a cultural vision forged from a traumatic childhood and the shadow of war. His pronouncements are characterised by a deep pessimism about contemporary cultural trends and existential threats to the very idea of European culture and of Europe itself. However, Demarco retains a profound optimism about the potential power of the language of art. It has achieved great things in the past and could, in the right conditions, do the same again.

“I’m clinging on”

This cultural dream is what drives him on still at the “ridiculous age” of 93. “I might not be around tomorrow” he says with some despair in his voice, but also an urgent sense of needing to make every day count. His diary is full of meetings and cultural dialogues. He is doing all he can to transmit his cultural vision, to ensure that it lives on once he is gone. This is what fuels his protracted, sometimes tangent-laden, pronouncements. His assistant

Terry Ann Newman mentions “all the batteries he has run” out, referring to the dictaphones and cameras of interviewers he has exhausted over the years. Demarco admits that he feels an “observable decline” in his physical and mental capacity in recent months; his own battery is running low.

The thought of being around for the 2025 festival is “a pipe dream”. He needs to use every day he has to communicate his message and build a team to continue his work and make sure his vast archive is put to good use. He needs people to be able to interpret what he has done, especially when he is no longer around to assist. Every photo or document he shows off leads to another engaging, urgent narrative: “this will blow your mind”, “ just look at that!”. There’s a sense of wonder about the figures he has worked with, almost a sense of disbelief. Alongside it is a sense that the cultural significance of what he has in his archive hasn’t yet been recognised. This has often been the pattern in his cultural life.

Deep wounds

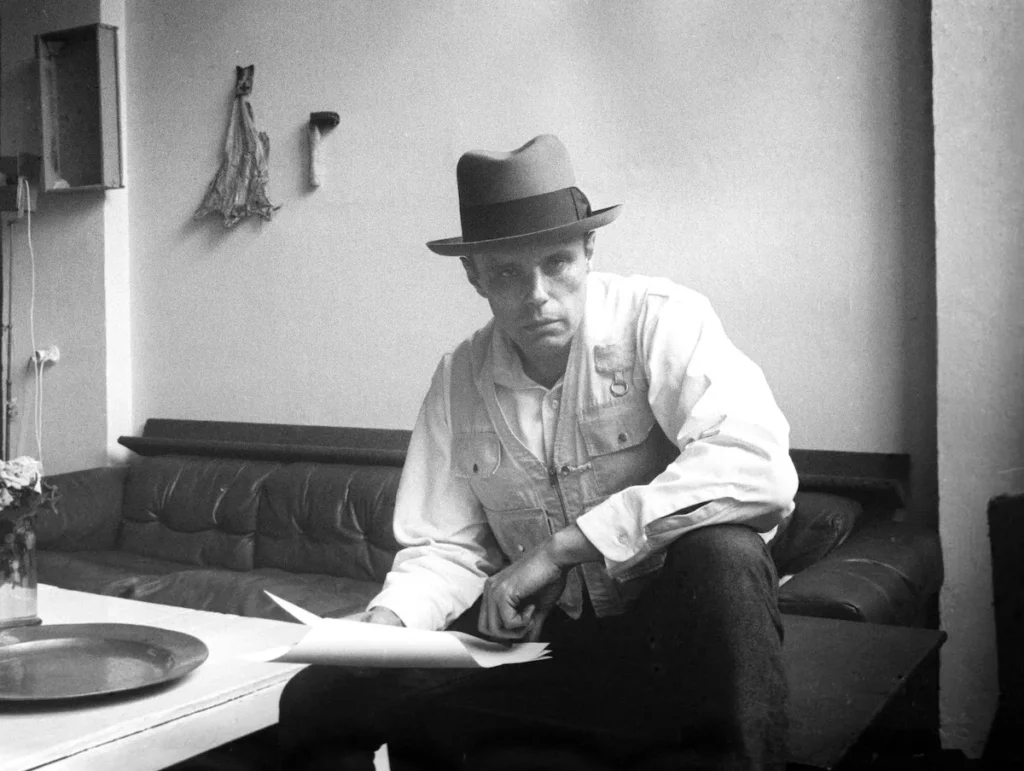

Demarco’s cultural vision is shaped by deep and enduring scars. These scars are embodied by the figure of Joseph Beuys, the key figure in Demarco’s cultural life. Demarco comes alive when recounting stories of Beuys, the table sometimes shaking as he speaks- the passion transmitting itself. That’s what is vital to him. Trying to keep his memory and cultural vision (and practice) alive is part of every public intervention Demarco makes.

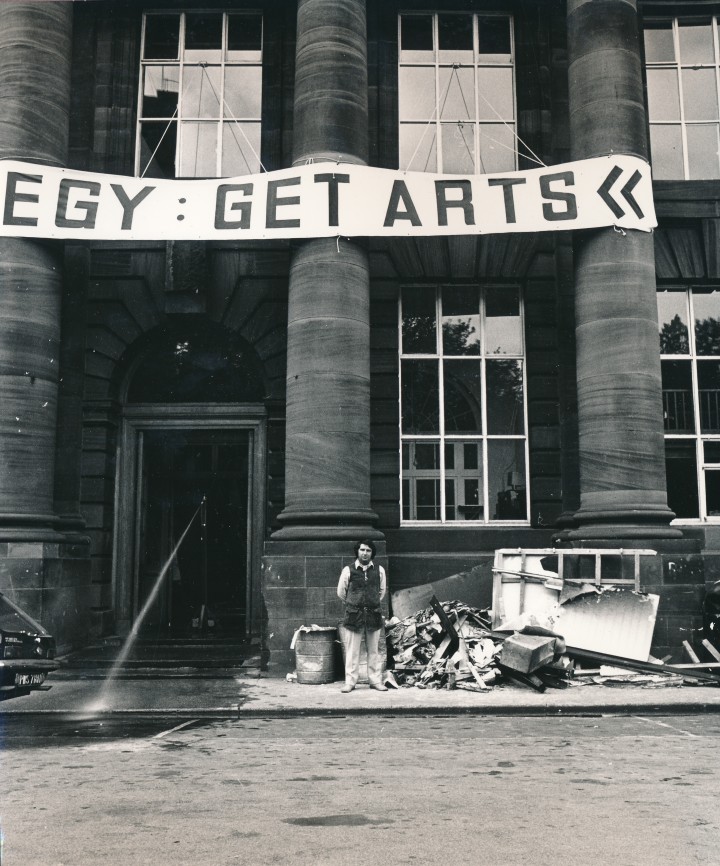

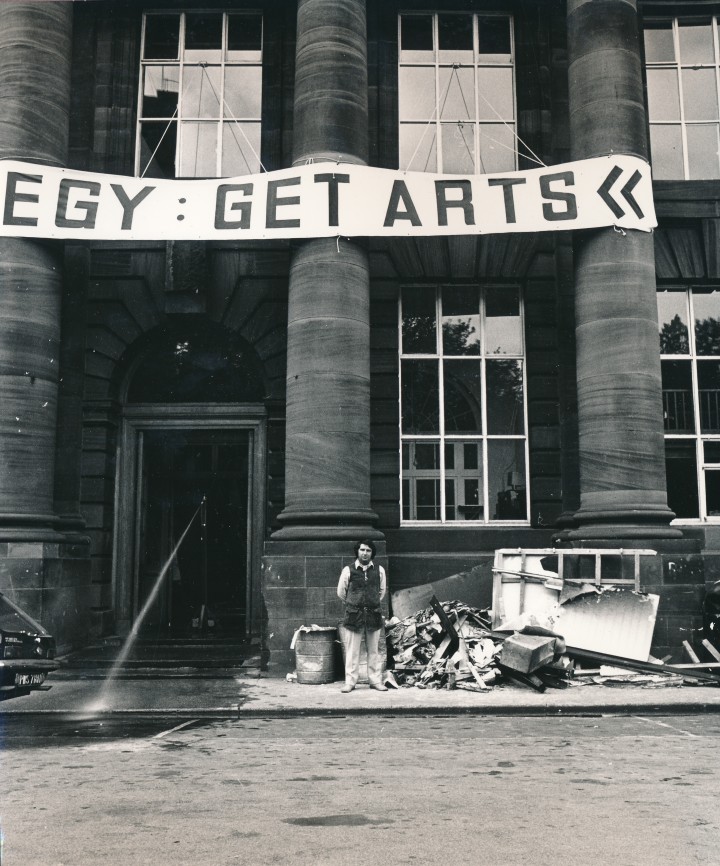

One of his most moving recent speeches was delivered after planting an Oak (in the courtyard of Edinburgh Art College) in Beuys’s memory, 100 years after his birth. Beuys was also a central player in the landmark Strategy: Get Arts. The 1970 exhibition, held at the College, is widely considered (including in David Pollock’s recent Edinburgh’s Festivals: A Biography) one of the key events in the history of the Edinburgh Festival.

During last year’s Book Festival, this sapling was often bumped into and some branches damaged. The oak is in danger of withering and waning. Beuys’ fascination with the oak was a reflection of his interest in ‘the mystery of time passing’, as they often live to be 300 years or more. This sapling may well have a much shorter life than that. Demarco might well see this as a stark visual manifestation of failure – of failure to maintain cultural ambition.

Gotthard Graubner outside ECA Main Building with debris of the ‘Mist Room’, with Klaus Rinke’s water jet spouting from main entrance (August 1970). Photo © Monika Baumgartl.

Beuys was well known for wearing a felt hat. Sometimes considered something of an affectation, he wore it primarily to cover the metal plate in his skull. This came from wounds suffered in a much mythologised crash during the war. These wounds drove Beuys’s desire to heal a wounded world, through art and his environmentalism (he was a founder of the German Green Party, Die Grünen).

Demarco’s own cultural vision was also profoundly shaped by the war but also by a deep sense of being marginalised. As someone with Italian heritage and a Roman Catholic upbringing and schooling, he was a victim of a “double whammy”, subject to taunts and bullying at school. His was “a childhood of misery and pain”. He and his fellows were seen as ‘enemy aliens’, with Churchill’s call to ‘Collar the lot!’ through the policy of internment. The sinking of the Arandora Star, which was carrying many Italian Scots to prison camps in Canada, remains a deeply painful memory for Demarco.

This prejudice lingered on, even when Demarco became an established cultural figure. He has constantly been turned down by ‘officialdom’. There was, for instance, a degree of resistance against a gallery appearing in the New Town/ West End with Demarco’s name on, so redolent were Italian names of ice cream and fish and chips, rather than art and culture. That sense of being an outsider persists. Being called Richard or Ricky has made him feel alienated from his real true existence, Rico (what he was called at home) or Riccardo, as he was christened.

I’m not a Scot, I’m a European

These are the deep scars which explain his profound passion for art and why his contributions to public debate are embossed with a strong sense of never being fully accepted- in Scotland at least. “I’ve had to fight to exist within British society- using the language of the arts in order to do so”. Culture has been his “ticket to ride”. Despite these efforts, his biggest accolades have generally come from the continent.

Instead he looks elsewhere, especially to Eastern Europe. For example at the moment he is renewing his already substantial links with Poland, a country with deep connections to the country. This includes the many Polish soldiers stationed here during the war. Polish is the second language of Scotland again emphasising the deep connections. Poland, bordering Ukraine now sits on the front line of the battle against tyranny. The physical reality of war fills Demarco with deep concern.

These Polish connections were explored during a recent visit from the deputy director of the Polish Ossoliński National Institute (aka the Ossolineum), Marek Mutor. This highly significant library and cultural research centre is an institution with, what Demarco terms, “a terrifying history”. Much of the library’s collections were deliberately destroyed or scattered during and after World War Two. It’s been in Wrocław since 1947, having originated in Lviv – now, symbolically, in Ukraine. Demarco sees Poland as a manifestation of the scarring impact of war (a country that had to endure Nazism and Stalinism) and which is once again on the frontier, with a looming existential threat.

Demarco was speaking in the ‘Polish Room’ of his archive at Summerhall. The display there shows a chronology of his engagements with Poland and its artists. For Demarco, “everything is connected, everything is about connections”. This helps give his narrative a coherence as he moves around the room. The display also provides a summary of Demarco’s life, including an evocative picture of him as an art teacher at Duns Scotus Academy in Corstorphine, leading a group of pupils. Demarco still sees himself as an art teacher, introducing people to culture they wouldn’t otherwise have discovered. He wants us all to access the deep meanings lodged within the best art, rather than be merely “cultural tourists” engaging at a superficial level.

Duns Scotus Academy is one of the three schools he attended or taught at that have since closed or otherwise disappeared from the map. The others being Holy Cross Academy (closed in 1969) and St John’s Primary in Portobello. The demolition of the original building in 2018 was condemned as a “scandalous act of public vandalism” by the historian Tom Devine. Though Edinburgh College of Art still remains, Demarco is sceptical about its current health and indeed whether the proper place for art is in universities.

Demarco is profoundly alienated from many of the institutions he has been involved with. This includes the Traverse Theatre which, in Demarco’s view, no longer stages truly challenging work. This is part of what Demarco sees as a general tendency to “play it safe” culturally, to put on work likely to attract good press and audiences. In contrast, Demarco has “always had a strategy”, focussing on the inherent quality of the work, not its commercial prospects. In short, not focussing on guaranteed successes and the big exhibitions that draw already established artists but looking to go beyond this. Many of the artists he worked with and championed have subsequently gone on to become seen as hugely significant.

Demarco’s contribution is more readily recognized beyond the UK. In practical terms, it may be that the future home of his vast archive will be overseas. A significant portion of the archive, sold to the National Galleries in 1995, will be housed in Granton as part of the Art Works scheme, a project which aims to “future proof how we care for Scotland’s national art collection”. However, Demarco sees the part housed at Summerhall as the most significant portion, of immense cultural value.

In particular, it is packed with material that tells the story of the Edinburgh Festival. It is. For Demarco, a physical manifestation of the original aims of the Edinburgh Festival. Demarco sees his mission, manifested in the archive, as recording and documenting the Festival as was. No one else has done it and no one else will do it. It would surely be ironic if this archive were to leave Edinburgh. Again, that sense of feeling alienated and unwanted. He expressed this disenchantment when threatening to burn the archive because, as he told the Herald, “no-one gives a damn about it”; no one in Scotland.

On the frontier

Poland also represents the frontier against an enemy that would seek to destroy the idea of Europe and European culture as a coherent whole. As he put it previously, “those fighting on the front line in Ukraine are fighting for us”. This sense of a European vision under threat from outwith (Putin) and within (the rise of national populism in Hungary, Italy, as well as “the disaster” of Brexit. Intriguingly, many national populists (such as Orban in Hungary, Meloni in Italy) argue that it is they who are defending western culture. They look to conservative thinkers, such as the late Roger Scruton, who saw the national state as the best defence of cultural continuity.

For Demarco, nationalism is the greatest threat to a coherent Europe. This is evident in his scepticism about notions of a distinct Scottish culture that, unconnected to Europe. Demarco constantly reiterates the inherent Europeanness of Scotland and its culture. Of the three political and cultural circles that intersect with the UK (Commonwealth, America, Europe), Demarco stresses the last. Attending the 1947 Festival made him recognize that “I was living in Europe not the British Empire”. Demarco is also concerned about the Americanisation of our culture, which he sees as something inimical to his European vision. These were themes he explored in the Beyond Conflict pamphlet, his response to 9/11, delivered to the European Parliament. Again evidence of his deeply European vision and the idea that art must be intimately connected to important issues of the day.

Ancient connections

Crucial to Demarco is the idea that Scotland had a significant place in Europe, on its western margins. When introducing Beuys to Scotland he felt like “a gatekeeper of a treasure house”. Scotland has so many treasures and interesting places. It’s a “country littered with stone circles” and other portals into the past. For instance, the Callanish Stones are probably more significant than Stonehenge, and certainly, Demarco believes “more significant than Scotland’s galleries and museums”.

Beuyys work struck Demarco at a deep level, providing access to things “beyond rational thought”. He was initially so awe struck that he couldn’t speak to him. When Demarco first spoke with Beuys, he showed him some touristy postcards of Scotland. Beuys saw in them an older Scotland, “the land of Macbeth and his witches”. There was a deep connection to a country on the Western edge of Europe, full of prehistoric landscapes and folklore; the Scotland evoked by Burns and Scott, as well as Shakespeare. This desire for something deeper, something visceral, something that touches the soul not just the intellect is what connected Demarco & Beuys. Through Beuys, Demarco was also further convinced that the Edinburgh Festival and Fringe must be ambitious in its cultural ventures.

Renewing the Festival

Those who observe Demarco’s public utterances might charge him with ‘Golden ageism’. Declinist narratives are very common in the cultural sphere. Perhaps to counter the view that he spends his energies focussing on the past, Demarco is putting on his ‘alternative Edinburgh Festival’ this July. It will be a personal history of the entire festival, from 1947 till the present. He’s been at all of them: possibly a unique record.

He wants to resurrect the Edinburgh Arts Project from 1974 on its 50th anniversary. He envisages a programme that centres on “Scotland’s cultural and academic dialogues with, in particular, Spain, Poland, Romania, Italy, Germany, Ireland, Belarus and Ukraine.” These deep connections are what continues to inspire Demarco as he continues his life-long cultural journey.

Demarco’s alternative festival is an effort to remind us of the Festival’s original vision. It stems from George Steiner’s view, expressed in 1996, that it was time for a fundamental rethink for the Festival. Steiner considered the Festival to be “an ailing echo of the original”, lacking a true “intellectual edge”. There was a lack of awareness of what cultural values the Festival was upholding. The whole thing needed to be “self-questioning” and think about whether it had had its epoch? Could it be revived or had it had its time. Perhaps like any great performer it just needs to know when to stop, when to step off the stage. Let it revel in its past and move on to something with new cultural energy. For Demarco, this question remains unresolved.

He is torn between a deep faith in the original mission of the Festival and a sense that it has gone completely off the rails, having started to do so in the 1980s. For Demarco, the need for the original mission is greater than ever, as Europe faces existential threats. The Festival was, Demarco suggests, “on the front line from the beginning”, bringing together a Europe ravaged by conflict. The same need exists today but is the cultural firmament up to the job?

This article derives from a discussion with Richard Demarco, Ed Schneider and Terry Ann Newman at Summerhall, Edinburgh on 13.2.24.

In August 1982, during the Edinburgh International Festival, Edinburgh College of Art mounted an exhibition entitled ‘On the Side of Life: Patrick Geddes 1854 – 1932’, designed by John L. Paterson. Richard Demarco was greatly taken with it and, rather to the chagrin of its curators, started conducting his own unofficial guided tours. I remember him starting one such tour by announcing to the group in his train that “This exhibition celebrates the work of the great Scottish architect, Patrick Geddes.” Geddes, of course, was not an architect, but he was just the sort of creative European polymath to appeal to Richard Demarco.

Brilliant Graeme, do you have the programme?

Yes. It’s one of my treasured possessions!

Really interesting article and great writing. Thank you so much!

Can a something like the Edinburgh Festival(s) keep to its original and arguably vital vision after many decades and changing times? I think not. Things have a natural lifespan. I would simply end it and start afresh in a few years time. But that will never happen as commercial interests will not let it. But the most frustrating thing is the complete lack of acknowledgment by those who lead the Festivals that anything is really wrong. I genuinely think they think there isn’t as remarkably they seem to have no idea what the foundational principles were. But then the bigger problem is the commodification of culture, all of it, including the apparently radical and challenging; everything has been subsumed as part of the capitalist paradigm. So the notion there might be something up with the Edinburgh Festivals does not even compute.

“ … the bigger problem is the commodification of culture …” Agreed, case in point the Edinburgh International Festival now operating a dynamic pricing policy on tickets like eg easyJet.

Demarco was/is a master of self publicity and money-making. An artist of charity-shop worth, but a great entrepeneur.