After Britain: the Collapse of British Identity in Scotland

The Scottish Census continues to expose interesting insights into who and where we are, our religion, our language our identity (of which more later). One of the standout figures from the survey results showed that 66.5% of people identify themselves as Scottish and only 8.2% identify as British.

The report stated: “The percentage of people who said Scottish was their only national identity increased since the previous census (from 62.4% to 65.5%). The percentage who said their only national identity was British also increased (from 8.4% to 13.9%). The percentage who said they felt Scottish and British decreased (from 18.3% to 8.2%).”

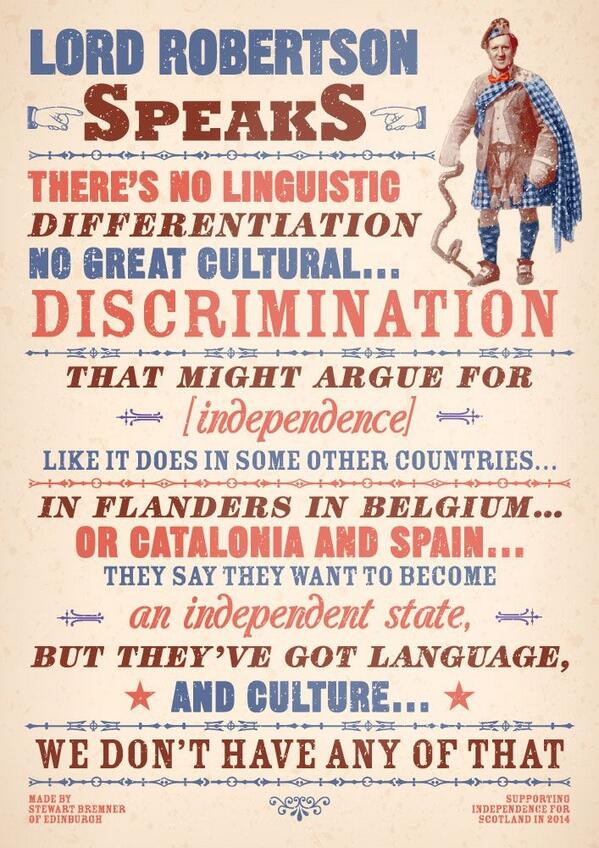

This isn’t hugely surprising. For the past forty years there’s been a quiet revolution in cultural renewal with emergent institutions and structures to represent Scottish cultural life. It’s a process that is hugely flawed, incomplete and inadequate – especially in terms of broadcast and and media devolution; support for indigenous languages; investment in film and tv and theatre; and Scottish-based publishing and literature. This magazine has explored these themes over and over for the past fifteen years and more. However, despite these failings, that are in part the result of not achieving sovereignty and in part the result of a failure of nerve and ambition within devolution, we have still seen a huge renewal of cultural confidence. People are far less ashamed of their own culture, feel it has worth and are able to both value it and critique it. We are minus key institutions to reinforce this huge change, but we are miles away from the sort of cultural cringe that used to dominate and undermine our cultural lives.

So 66.5% isn’t going anywhere and the trajectory is only going North. What this means politically is a different matter. Jim Sillars famous accusation of ’90 Minute Patriots’ may still hold clear, or more so 80 minute ones. There is a performative aspect to proclaimed Scottish identity that might have no political outcome than wearing your kilt at Murrayfield.

But in the long-term these things do matter. It is not surprising that after decades of decline and shame and shambles people don’t want to be associated with Britain or British identity. When I was a child the Union Jack was seen everywhere, other than a brief spell with Geri Halliwell and then with Cool Britannia it has gone – only to be associated with the far-right or enclaves of loyalism. It’s there when there’s a state occasion – another jubilee – coronation – death – birth – but its ubiquity and power as a unifying symbol has not survived. This is not just about the rise in Scottish nationalism but the failed attempt to resist the ongoing rise of English nationalism and identity.

It’s interesting to note that the percentage who said their only national identity was British also increased (from 8.4% to 13.9%). This could be a hardening of British identity by those who feel under ‘threat’, or that they wish to display their British Unionism. Or it could be people relocating from England who identify as ‘British’.

Perhaps more worrying for those who realise that British identity is wrapped-up with political choice, the census tells us that those who feel “Scottish and British” fell from about 1 in 5 to about 1 in 12. That’s a disappearing generation and a disappearing identity. That’s not coming back. What this points to is the fact that feeling “Scottish and British” increasingly feels either impossible or unattractive or both. It suggests that there is a choice: increasingly you have to choose to be Scottish or British, the two notions are incompatible. You may rage against this, you may claim that its not impossible and it’s not unattractive but the data as laid out is pretty clear. A decrease of the percentage of people who felt Scottish and British from 18.3% to 8.2% is huge.

There’s an up and a downside to all this ‘Scottishness’. I want the political agency of self-determination. I want to live in a Scottish democracy. I don’t want my / our identity to be a substitute for that. It may be that this 65.5% continues to grow and it becomes an agent of change, a quite assumption with real-world political consequences. Why would someone who considered themselves Scottish not want Scotland to be a fully-functioning independent state?

If Brexit was billed as an attempt to project a ‘Global Britain’ it has failed spectacularly. Despite (or because) of the grotesque rhetoric from Boris Johnson and his colleagues post-Brexit Britain seems a harsher, crueler place as people are handcuffed and deported to Rwanda, as the John Woodcock report emerges, as the latest ‘scandal‘ unfolds.

Living on the outskirts of Anglo-Britain’s wreckage, viewed from the Celtic Fringe, Britain has been a memefest of indulgence in hyper-nostalgia for the last decade, the new version of Spitfire Nationalism allows you to hurtle even further back. Scattered among the poppies and the royals and the endless remembrance is a recurring meme carefully cultivated by the Leave leadership, that of conflating Brexit – and specifically No Deal Brexit – with “our finest hour”. In this landscape it’s no wonder that Britishness has died.

Excellent article. Brings home and opens several important issues for all Scottish/English/British folks. Thanks.Joe

Thanks

Ireland, Spain and Norway will each formally enact recognition of a Palestinian state on 28 May. Such a pity we don’t have our own State and could make a real contribution towards creating a more peaceful and tolerant human population on this planet.

I suspect one of the reasons why those who identify as ‘British’ has increased from 8.4% to 13.9% is, as you hint at, from incomers to Scotland, but, I suspect that it is not white incomers from England but people of colour. In order to be granted a UK passport, people from countries outwith the U.K. and Ireland have to undergo tests to prove how much they know about ‘Britain’. Having past the test and having been granted a UK passport, if they are people of colour or have a pronounced ‘foreign’ accent or both, they are much more likely to be asked ‘where do you come from?’ or ‘what nationality are you?’. And fearing arrest and possible deportation after many years of the ‘hostile environment’, they will say they are ‘British’. By stating that they are ‘Scottish’ – an identity, increasingly, viewed with suspicion – in some parts, this, too, might lead to arrest and possible deportation.

If they identify as ‘English’ there will be less suspicion, because ‘English’ and ‘British’ are viewed as synonymous – as Rishi Sunak said ‘Britain is another word for England’.

I think those identifying dually as Scottish/British will be mainly septuagenarians and older, who, like I do either remember the war or had parents who served in the war. I identify as Scottish as did my father who served in the war in North Africa from 1940/44.

In a census, the purpose of which is to target services, asking people how British they feel seems pointless. Is it a political question foisted upon the Scottish census by politicians?

So which services was the 1842 census targeted at ?

I agree these census results are interesting and indicative of a general shift in views. But ‘national’ identities and labels are complex/subtle things, not necessarily tied to flags or a view of the constitution, and a census can’t capture all that. I was born and brought up in England, left all ties behind and moved to Aberdeen in 1976. I have lived in Scotland ever since, through all my adult years and working life, and absolutely regard Scotland as my home. I abhor the British state, the Union Jack brings me out in a rash… (though I’m not particularly keen on over-use of Saltires either – waving flags never ends well in my view!) I am a republican and a socialist who strongly supports independence for Scotland. But I don’t like to call myself Scottish, because that can be interpreted as meaning the country of your birth and I don’t wish to mislead or seem to presume. If asked abroad, I might say I come from/live in Scotland, but British was often a useful term for someone with my background. I saw it as a collective, geographical term in that context: we are part of what are widely known as (through the circumstances of history…) the British Isles and I have lived in two different nations within that group. But unfortunately now, stating you are British can suggest some assertion of British Nationalism in opposition to Scottish independence, so the term is more loaded than ever. Perhaps after independence more of us can feel comfortable using both British and Scottish like, I assume, folk in e.g. Norway who are happy to be known as both Norwegian and, more broadly, Scandinavian.

The problem is that Britain has become identified as a State, rather than a geographical region. This raises irreconcilable problems of identity. For example, you can’t really be a British subject and a Scottish citizen at the same time. Scottish and European would be a better comparison with Norwegian and Scandinavian.

This is true but the fact remains, British is also a term that is not necessarily tied to a state. At the end of the day, there is one big island with three different nations on it and it is called Britain or the British Isles to be more precise (though that terms also includes the island of Ireland). Europe is much too broad a term to encapsulate that (and I think the Scandinavian analogy does not work anyway as it is not an island).

The question CathyW’s post raises is quite profound: who qualifies to call themselves Scottish? And the hardest one that stems from that is does a person with English heritage living in Scotland qualify? And if not what are they? If they can never be Scottish, and British is regarded as redundant, they can never be anything other than an English ‘foreigner’. This is not the inclusive Scotland of civic nationalism.

Europe is a term which apparently suits 20 odd sovereign states perfectly well, and Ireland most obviously given the attitude that the British State has exhibited to Ireland this past few years, so there is no reason to suppose that it would not suit Scotland. I don’t see Czechia getting sentimental for the Hapsburg Empire. No-one suggests that the individual in Scotland cannot choose whatever sentiment he chooses regarding identity but that hardly seems entirely practical for the Scottish State. You may not have noticed recently but the British State is emphatically not our friend and absent major reform of its attitudes and constitution it is not likely to be in the foreseeable future.. There is no question that we should pursue a common bond with our neighbours except for the slight problem that our neighbours are bastards.

You can travel from Europe to Iran with one footstep BSA. The most populous city in Europe is currently Isanbul.

Very true, and Scandinavia does not have one large and overbearing member which has always claimed ownership of the others and is likely to continue with that principle, and where possible the practice, however amicable we might try to make the parting. Unless there is a huge and currently unlikely reform of the Imperial British State European identity and also membership will be essential support.

? Britain is a state, as in the United Kingdom of G. Britain & N. Ireland.

You are Scottish. You have been in our country for nearly 50 years, therefore you have chosen your nationality. Bless you.

In one important case, that of historical acknowledgement and reparations for crimes of the British Empire, I insist on being counted British. That is the only responsible way to have a say (maybe even a vote) on such matters, and to contribute.

In the imperial sense, we have to acknowledge those living outside the boundaries of the British isles who consider themselves British — or who do not. The Union is represented in many of the flags of these territories, although some proposals for new designs are made from time to time. Perhaps that would make a nice article with infographic and suggestion space.

Interesting take. In a way that means you will always ‘be’ British as the Empire will always have existed.

Tbh I don’t place as much store in these questions of identity as most seem to. I would rather have a fluid identity and not one fixed to any kind of ethnicity or nation state. Ideally I would have no such identity at all though that is a fantasy, I realise. I don’t translate that to anyone else as each to their own but it can be frustrating when so many seem to assume that it really matters to everyone. In terms of society, I wish we would stop ‘identifying’ so much full stop, all these tribes. It gets forgotten that when you identify ‘with’ or ‘as’ it is, by definition, something external to you not what you are.

Picking up a few points from these responses. Britain (Great or otherwise) is not a nation, it may be taken loosely to mean the state. More accurately, it is the UK which is a state, but not a nation. Scotland is a nation but not (yet) a state, i.e. a stateless nation. Britain consists of many more than 3 islands! I don’t see why my analogy is invalidated by Scandinavia not being an island? I am also, of course, European (and the EU is not synonymous with Europe) – as are Scandinavians – and, er… a citizen of the world, obvs.

The British Isles is a geographical collection of islands that is made up of 5 nations, Ireland being the only independent state. The UK as stated, is the state that comprises England, Scotland Wales and NI. It is also regarded as part of the continent of Europe. Great Britain is the the name used for grouping England, Scotland and Wales together as a single island. The UK is also known as ‘Great Britain and NI’, though there may subtle legal distinctions between these that I do not understand.

Scandinavia is an area of northern continental Europe comprising 3 nations states with close historical, cultural, and linguistic ties. Some include some of Finland too but not everyone.

Not saying there are not similarities, sure, bit the translation is not direct.

I take your point Cathy. ‘Britain’ implies forgetting about N. Ireland, and the ‘UK’ is more accurate seeing as no-one can be bothered with what could be the longest name of a state in the world.

I’m confused by the headline numbers reported here – the census says the percentages for Scottish only, Scottish and British and British only were 65.5%, 8.2% and 13.9% and yet the headline and graphic talk about 66.5% Scottish and 8.2% British. Yes the numbers have shifted but it undermines your argument to get the figures wrong in the discussion. Arguably Scottish-and-British recognises the British state as much as British-only and therefore the headline pattern could be described as ‘Scottish’ increased from 62.4% to 65.5% and ‘British’ decreased from 26.7% to 22.1%.

I’m confused about why the Scottish census contains a social attitudes question. The most important questions in it are ‘where do you live?’ and ‘how old are you?’. I don’t think that ‘Scottish’, ‘Scottish/British’, whatever, means that the different groups need information printed in different languages, or different provision of social and health care, or different anything.

Yeah, its all meaningless

Satan – if you had stopped what you wrote after ‘I don’t think’ we would all have been in agreement with you because your trolling posts fully support this statement.