People, Peat and UNESCO Heritage Status

This is the first of a two-part series look at the history and future of people within the newly designated Flow Country UNESCO World Heritage Site.

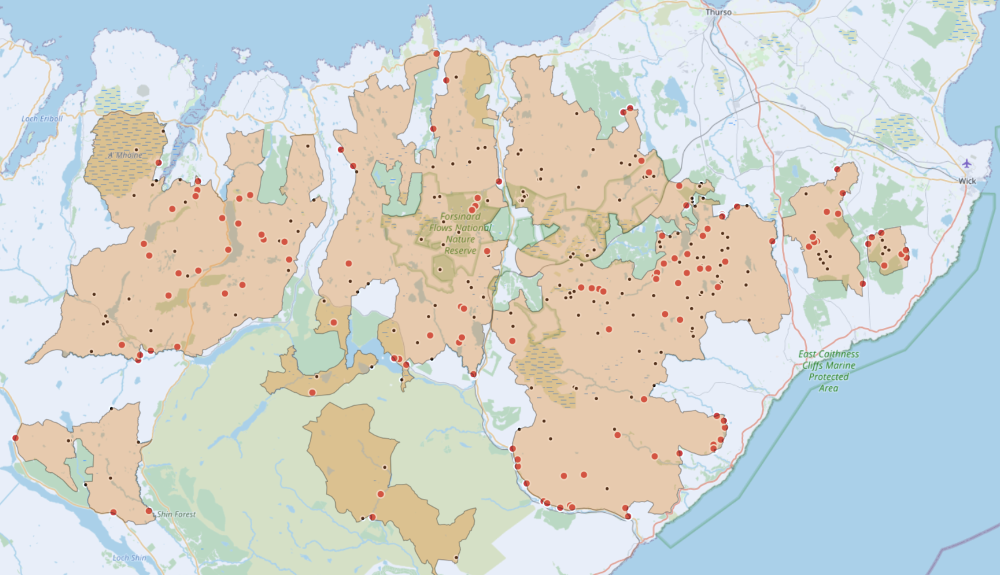

Map of the Flow Country with settlements (red) and shieling sites (black). Shieling sites may have one or more shieling huts contained within.

Last month the Flow Country, straddling Caithness and Sutherland in the far north of mainland Scotland, was awarded UNESCO World Heritage Site status, the first peatland in the world to be recognised, and one of only five wholly natural sites in the UK.

The narrative of the Flow Country, as it has only come to be known in the last half century, has largely centred on controversy arising from afforestation in the 1980’s of large areas of ‘wild land’, where much of the embellishment of the infamous planting came off the back of the links to tax breaks, particularly utilised by household celebrities who were taking advantage of the schemes. Terry Wogan is often at the top of the list.

Terry Wogan invested in a block of forestry, outwith but adjoining the newly designated area, at the southern end of what is known locally as Broubster Forest. The block of forestry lies a few thousand metres from Broubster Village, a neat little square of twelve ruined homes which were built to house families evicted from the surrounding area.

The forestry was planted on what was once Reay Commonty, which underwent a division, i.e., taken out of communal use, in the 1840’s at the same time as the eviction and clearance of the resident population.

Land taken out of common use and cleared of its resident population does not fit the narrative that we’re used to, of Terry Wogan’s forestry being planted on pristine peatland, although it’s not an unusual theme across large swathes of the Flow Country.

The recent designation of the UNESCO site will hopefully offer a revitalised position to examine the Sutherland and Caithness clearances and the future role for human habitation in the area. Themes that have struggled to be examined through the lens of conservation and restoration of these peatlands, despite occupying the same landscape and similar positions in the Highland psyche.

In the early 1950’s, at a time when the government owned greatly more landholdings in the north, my grandfather an Assistant Lands Officer for the Department of Agriculture for Scotland helped to spearhead planting initiatives. In papers written for his family he outlined:

“Over the next few years, I set out, and the estate men planted, larger acreages at West Watten and at Dalangwell. After ten or so years the possibility of commercial timber growth of selected species, mainly Lodge Pole Pine and Sitka Spruce was high enough for the Forestry Commission to acquire and plant larger and larger areas in the hitherto treeless north. The West Watten Plantation was laid out over deep peat, up to 14 foot in one area.”

His focus was on shelter belts for livestock, but he worked closely with the Forestry Commission who aspired to much larger areas of planting.

Broubster Clearance Village – Built in 1839 to house the families cleared from the surrounding farms and cottages. The last inhabitant left in 1952.

In the years before his death, we spoke about the value that the Flow Country, a name he disparaged, brings in terms of climate and biodiversity benefit. He never quite could get his head around the fact that, in his traditional agricultural terms, the land wasn’t being more productively used.

Whilst I couldn’t agree with his position, it wasn’t difficult to empathise with why he thought it. His worked connection to the landscape manifested itself in a certain way, not unlike the environmental scientists and conservationists, who frequently spend days, nights, and weeks on the bog, and who have worked for decades and careers towards this designation.

He was a post-war incomer to the area from the northeast, and soon married a Mackay, my grandmother, generationally displaced into the town of Thurso, by eviction from Strathnaver and Kildonan.

The view down to the township of Greamachary and Strath Halladale. John McPherson, who once lived in Greamachary, was famed for planting a rowan tree for each of his 7 children, which then died as they died

The Flow Country WHS boundary covers 187,000 hectares of land stretching across Caithness and Sutherland. Initially the Flow Country was largely defined as the area of peatland between the River Naver in the west to the River Thurso in the east. Over decades the definition stretched further west, further east, and further south.

The new, clear, and consulted on, boundary of the WHS is largely made up of existing statutory protected areas, which in places has been stretched to match wider water courses.

The lack of definition of the wider Flow Country has caused issues in debate on development, is the Sutherland Spaceport at the ‘heart of the Flow Country’? Or does the increasing prevalence of onshore wind farms, helping to decarbonise Scotland’s grid and usually built on previously afforested areas, keep encroaching on the area?

The boundary of the WHS should help to alleviate some of these concerns, at least in planning considerations, and allow us to answer further interesting questions: who owns the Flow Country and what has happened within it?

Using data from Andy Wightman’s Who Owns Scotland project, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, and the Scottish Government, I’ve spent time in the darker winter months trying to answer the land ownership question. Prior to the designation, the lack of a clear boundary has made it difficult delineate and map.

With 99% of landownership in the WHS accounted for the numbers are remarkable, if not unsurprising. Across the area, 52% is owned by only 7 landowners, 63% is owned by only 10 landowners, and 87% is owned by only 20 landowners. These statistics are not based solely on privately owned, or rural land, which is a definition widely used in other commentary on the matter, this is all the land found within the Flow Country.

The largest landowner is Anders Povlsen, Scotland’s largest private landowner, through his company Wildland Ltd. The RSPB are the second largest landowner. Both manage the land for conservation. The other large landowners, bringing the total to 52%, are the traditional sporting estates, owned by Viscount Thurso, Bighouse, Lochnaver, Syre and Rhifail, as well as state land owned by Scottish Government Ministers. The preparatory work for the bid was funded by the RSPB, Wildland Ltd, the Scottish Government body NatureScot, and the Highland Council.

One twentieth of the Flow Country is effectively owned by the nation, largely as a crofting landlord across two estates, but also the National Forestry Estate in larger plantations and a myriad of smaller pockets adjoining areas of better peatland. In total 83% is owned privately, 11% in environmental NGO ownership, and the remaining 5% by the state. There is no community ownership or quasi-community crofting ownership across the whole area. There are however significant crofting common grazings, albeit difficult to quantify due to current limitations of crofting land registration.

Across the wider Flow Country, encompassing 400,000 hectares, it is expected that restoration of degraded peatland could deliver £1.4bn to £4.2bn of carbon credits to landowners over the course of a century. A proportion of this will be delivered from within the WHS, where the hope is that the designation will drive a higher ‘charismatic carbon’ price per carbon credit sold. This raises an interesting question on who will benefit, as the land is so heavily concentrated in such a small number of privately owned estates.

In early June the Guardian picked up the story of the impending designation and highlighted, for the first time in any type of mainstream media, the relationship between the Flow Country and the Highland Clearances.

Remarkably, considering the Flow Country is intersected by Strathnaver and the Strath of Kildonan, the issue of the Clearances has largely been missed in contemporary debate. The forestry plantations came 150 years after people were cleared from the land to make way for sheep, and subsequently kept empty for grouse, deer, and conservation.

During the application process I was asked to write some of this social history for the bid documentation that was submitted to UNESCO. The text covered the pre-clearance period, transhumance, evictions and clearances, drainage and improvement, grouse and deer, forestry, conservation, energy, crofting, and landownership, among some other related subjects. It was important to be included, as although this is a natural designation, social, economic, and cultural elements have significantly impacted its environment, and not always negatively.

A longhouse from the township of Allt Stionachh Coire – now under ownership of Scottish Government Ministers.

However, the submission raised more questions personally than it answered, which subsequently led me to embark on a more methodological approach to answering the question of how peopled was this landscape?

Using a range of data sources, I have found over 125 settlements within the WHS and spent years visiting many of these sites. I have spent just as many years collecting and collating historical records to understand population change across the area, both in place and in time. It may not ever be possible to answer the question completely. But many, that is the vast majority, of these townships and farmsteads were significantly impacted by the Highland Clearances.

Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster, the first person to coin the English word statistics in his pioneering Statistical Account of Scotland, and often credited with being a driving force of heralding in the clearances, evicted residents from the Berriedale straths in the 1790’s, shifting the resident population to the infamous Badbea clearance village. The Berriedale straths, and their associated settlements are now largely included in the WHS.

The old shepherds house at Allt Stionachh Coire – now under ownership of Scottish Government Ministers.

My own connection to the east of the Flow Country comes from a fourth great grandmother, Anne Sutherland, who was evicted from the Strath of Kildonan, at the age of 16. Her township lies slightly outwith the WHS but her and her family will have used the area and its shielings during the summer months in the practice of transhumance. In Strathnaver, to the northwest, another set of fourth great grandparents, Neil and Janet Mackay were cleared to Strathy Point, now a crofting estate owned by Scottish Government Ministers, and lived the same seasonal life within the designated area, before being evicted from the Flow Country.

The township of Benalisky – The families of Hugh Mackay, Angus Mackay, John Reid, William Gunn, and Neil Gunn used to live here

Over 600 shieling huts, across 185 sites, can be found within the WHS showing an additional large seasonal residence. The Ca na Catanach drove road cuts right through the centre of the designated area, and Bad nam Bò, one of many Gaelic placenames found across the peatlands hints at its long-lost land use.

The then lack of afforestation, agricultural drainage, and sporting management, all suggest that the bog was in far greater ecological health when it was more populated and managed seasonally in the practice of transhumance. The first and second Statistical Accounts hint at this process, which is greatly endorsed by a catalogue of historical records, not least various estate’s own records. There are few better descriptions and explanations of this hypothesis than in the final chapter of Reay Clarke’s book Reay Country, Two Hundred Years of Farming in Sutherland.

The Flow Country’s largest landowner, and current owner of the land Reay Clarke’s family farmed, gave an interview to the Sunday Times a number of years ago where he stated:

“I worry that the vision of the past in the Highlands is misplaced. Yes, in some of the glens there might have been many families, but they had an impoverished life.”

My daughter’s family, on her mother’s side, were cleared from a small piece of Beinn Laghail hillside now under Povlsen’s ownership. The township has three longhouses, visible runrigs, and a grain kiln.

Whenever I reflect on ‘impoverished lives’ I am struck by the words of Angus Mackay who, like my Mackay forebearers, was cleared from Strathnaver to Strathy Point. When he was asked by the Napier Commission of life before the evictions he responded:

“Remarkably comfortable —that is what they were—with flesh and fish and butter and cheese and fowl and potatoes and kail and milk too. There was no want of anything with them; and they had the Gospel preached to them at both ends of the strath.”

The Flow Country was once more heavily populated than it is today and during this time the ecology was in better health. That was however 200 years ago. There are very small and dwindling pockets of human habitation within the WHS now, most associated with estate ownership, itself a relic in ability to keep people in this landscape.

We no longer produce cattle in these peatlands to send south. The majority of the sheep of the interior were a failed economic experiment. The remaining grouse shooting is minimal and walked up. The deer numbers are too great with benefit accruing to few people. New rewilding money in the area is following the same commercial, or lack of, model of old.

Many will be happy with the suggestion that carbon credits born out of the labour of a local workforce, or ecotourism guides catering to incoming tourists will suffice as local benefit, particularly when the workforce is nearby. Anyone with a closer understanding and connection to the landscape should be asking: is this good enough?

Picture credits: Magnus Davidson

An interesting and thought provoking piece. Historically the area provided a simple living to many more than live there now but while the idea of repopulation is attractive in is probably impractical in any significant way in today’s society.

I look forward to reading comments better informed than mine

Why would repopulation be impractical here or anywhere else in the highlands and islands?

Precisely!!

Significant repopulation needs houses, roads, water and somewhere to restock the larder. Not many people are prepared to live without them. The abandoned clachans were populated by people who lived a very simple life, few would take that on now. Yes the outskirts can be repopulated but I believe much of the area is too remote without unacceptable construction. As I said in original post I’m happy to be proved wrong as my knowledge is limited.

Yes, you do need to think about what will sustain people there today, and not just assume you can replace like with like.

It is a very interesting question. In many ways it is asking ‘can we live in the same non-destructive state of harmony with our environment / nature a similar way to some of our ancestors’. The answer must be ‘yes’ but how to do it?

You are right that setting up new communities with the expectation they live in pretty much the same way we all generally do today (with all its roads, mod cons, cars, power demands, ‘fancy’ foods, schools, internet etc etc) is not it and a very long way from it so it would require a population who really did want to live in that more harmonious way without many of the trapping and expectations of modern life. It has happened before, after a fashion, with back-to-nature, hippy idealist types but in 2024?

I think it is possible but requires a genuinely radical approach to what re-populating such places really entails.