A Country of Independent People

A country of independent people – who truly know themselves – is, and always was, the real prize, argues Christopher Silver.

I imagine my friend Roddy driving back up from RAF Prestwick in the summer of 1989; the wide Ayrshire coast blue and broad on a day of freedom; a Silly Wizard tape blaring out, thoughts of the weekend and the hunt for music. I imagine Roddy registering a change in the evening air on the sure path to his local.

I never asked Roddy about what had happened to him earlier that day in 1989. The day he had decided to tell an RAF security vetting interview that he was gay. He did so with the knowledge that this would almost certainly end a promising career and the life he had lived since childhood: from his family’s posting to a colonial outpost in his infancy, through to military boarding school.

That day in that room was the fulcrum of a life: balanced on one side was the camaraderie, tradition, the love of martial music, the work of applying yourself to something far bigger and following the same tune. On the other there was simply the truth. On that day, the balance tipped away from all that he had known.

I never asked him why, I reckon I know what swung it in the end: doggedness of epic proportions. The trait of all stalwarts, it was the doggedness of such people that made the turn towards what he knew about himself inevitable, and that later defined the summer of 2014.

I choose to imagine that he drove home with a lightness to his bearing, along a bright coast. There were plenty of dark days that would unspool after that truth had been spoken, but let’s give him this moment of liberation, the elation of saying ‘fuck it!’ to a system that has ground you down that so many of us have known.

Military service, homosexuality and Scottish nationalism. For most of the last century, these three strands did not make for an easy mix. But they were Roddy’s lot. They were not chosen; seldom wrapped up in the easy language of identity and celebration. In the half century of his life they were mixed blessings; often burdens.

The twin experiences of deep betrayal and equally deep belonging became a knot in the man’s mind. Persecution will do that.

The contending strands of possible lives get tangled up in each of us; but fitful moments of singularity remain. With Roddy, we might cite the moment he leapt up from his habitual spot in the corner of Edinburgh’s finest (and rowdiest) folk music pub in response to a disgruntled punter who had just called the barman a poofter, to proclaim without missing a beat: there’s only one poofter in this pub! Or his iconic stand off with a still more disgruntled customer who said he looked like the Muslim cleric Abu Hamza crossed with a character from the Wickerman. Or his – idiosyncratic – rendition of ‘The Galway Shawl.’

To arrive young (as I did) into a world of characters like Roddy is to mistake their presence for permanency and to assume that some kind of logic led them to those cheerful moments in a warm room. Many of us live and die restless, but a fine story tells us that a life of jarring and conflicting paths will end with the ease of resolution.

Roddy was one of thousands of gay men and lesbians persecuted under the Ministry of Defence’s disciplinary codes – contained within the Army Act 1955, the Air Force Act 1955, and the Naval Discipline Act 1957 – which banned ‘conduct of a cruel, indecent or unnatural kind.’ Decriminalisation of same-sex acts between men over the age of 21 in private in England and Wales (1967) and Scotland (1980) arrived with specific exemptions for the armed forces, which held on to its policy of exclusion until an EU directive overturned the ban in 2000.

When Roddy’s life was upended because of the stated truth of same sex attraction in the 1990s, the military and political establishment of the day clung to its homophobia like a talisman. From closeted young Defence Minister Michael Portillo to his party’s grand dame – Armed Services Minister Nicholas Soames – all were adamant that morale and national security justified the routine surveillance, interrogations and punishment of gay service personnel.

Soames insisted the British military should not be ‘bludgeoned out of the esprit de corps that has won every war since 1812’. At a Select Committee hearing Labour’s Dr John Reid asked of Stonewall’s Director Angela Mason, ‘Do you accept the right of a woman to refuse to shower with a lesbian?’. Mason’s baffled response is to a voice from another era.

Identity and progress were the two words that were supposed to have defined the times that Roddy lived through. But we think too neatly in supposing that the grand sweep of liberation lifts all boats. To live differently, openly, and to make old institutions anew is work that requires the sacrifice of bodies, livelihoods, certainties. All the while old ideas linger.

The MoD’s codes went further than civilian prohibitions – for example, persecuting lesbians as well as gay men – but masculinity was at the core of post-war anxieties about gay sexuality, military discipline and morale. The cultural historian Matt Houlbrook argues that a new moral panic about the well-established homosexual subculture within the elite Brigade of Guards in the fifties was fed by novel anxieties amongst the establishment. As the empire disintegrated, homosexuality emerged as a ‘predatory and lustful danger to the nation and its manhood,’ which ‘embodied a wider postwar crisis of Britishness.’

Beware the wrecking ball of another’s insecurity. Roddy’s Scottish nationalism was deeply informed by the hypocrisy of the British establishment’s celebration of the outmoded and the indefensible, with no thought for the damage it did. Here indeed was a thoroughly queer world of old boy’s networks, idealised youthful masculinity: the irrevocable damage of boarding school and its needless cruelties.

Roddy found solace instead in the humanism and popular folk traditions promoted by his friend Hamish Henderson, a fellow champion and practitioner of sexual liberation and an ex-serviceman who saw in the end of Britain a new dawn of liberation, ‘Though ye bigg preesons o’ marble stane/Hert’s luve ye cannae preeson in’.

We didn’t talk about politics. Roddy was a self-described one nation Tory devoid of a home (and trust me, witnessing an impromptu performance by Ruth Davidson of the ‘Fields of Athenry’ only cemented this homelessness).

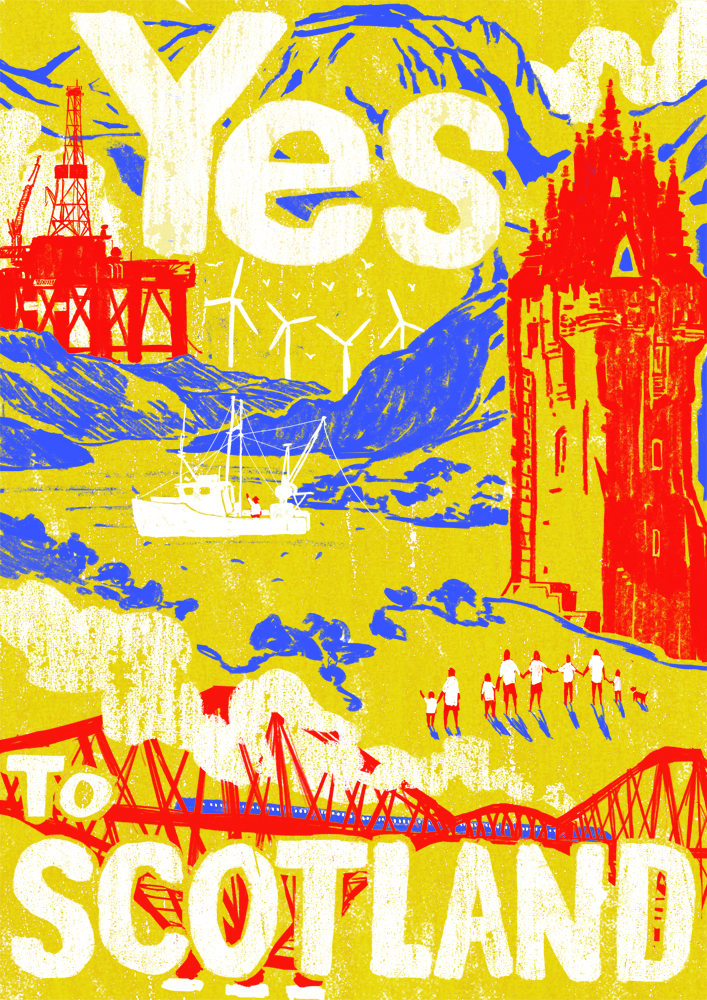

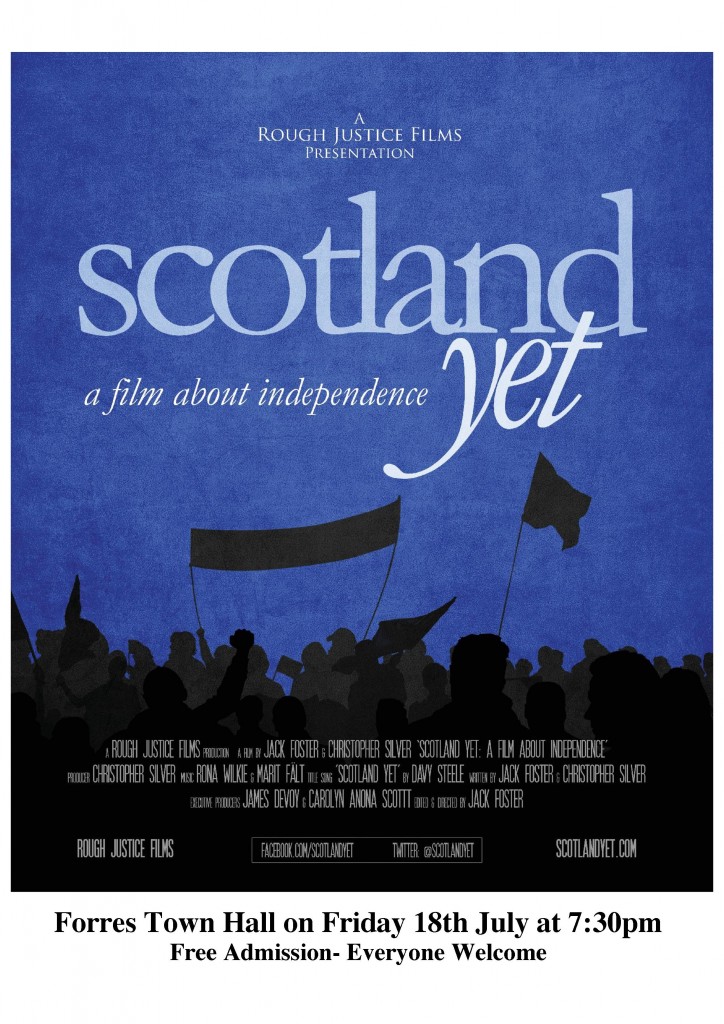

As a member of the campaign group Rank Outsiders, Roddy beat the establishment; losing so much in the process. The Yes Movement was a coalition of outsiders too: of people who sorely needed the new forms of community that 2014 gave life to. It seems strange to say this but it all seems curiously apolitical now. There was no real programme, no vanguard, no systematic political thinking beyond hoping that a hostile world would open the door. We did so much learning about how to accept ourselves that we assumed others would too.

I don’t think this lessens the significance of the movement at all. Identity often seems to emerge when community is lost – but Yes was in this sense the opposite of identity politics – it was all about rediscovering community and bringing your entire self to be immersed in it.

To congregate, to share public space, to see older forms of collective struggle in a moment of historic recognition: it seemed possible that progress might not fly blind like a storm, but could be tamed to address this small matter of justice and equality.

We thought that we could walk from a troubled past towards a place of quiet resolution.

Ideology was mostly absent. So when the movement fell apart it was unusually acrimonious: communities, far from places of easy grace, involve hard graft and the endless defence of rules and boundaries, they have a habit of splintering into shards of exclusion and recrimination.

The divide that still exists in Scotland is all about priorities – if your life makes you cling to the raft of community in an uncertain world, if you immerse yourself in a culture because it feels like home and freedom, there will always be the temptation to say ‘fuck it’ to the systems that seek to squeeze the life out of you.

But today – in a country where so many are reminded every day that things don’t work and few care – the living form of Scottish culture is sick and waning: riven by culture wars, battered by the pandemic and barely registering in many of our five million day to day lives. Ten years on, resolving an old tension within Scottish nationalism becomes critical: is independence about Scotland becoming normal, and much like anywhere else? Or is it about nurturing that which makes Scotland distinct?

A hunger for normality and liberation are strange companions. Yes was a movement for the vulnerable and the sentimental; the idealist and the chancer. But Scotland has never belonged to people who live by those traits. It still belongs to those who looked on, horrified, at the street politics, the camaraderie, the sheer fun of it all (far too much fun, if we’re honest, to be any kind of revolution).

You’ll have had your liberation says the douce old country today.

We walked out of Roddy’s funeral to the lilt of Donald Shaw’s ‘Calum’s Road’ – the version by Pipe Major Bill Hepburn – which trades the grace notes for something more raw and eternal. There is no more fitting anthem for the dogged, the independent.

I go to lots of these funerals now. So many wild nights of wild songs have taken their toll. It’s the song yes, but the singing, really, that touches the edges of freedom.

You spend the first part of your life being told that your obsession with music and culture and poetry needs to be reined in, only to find that in the second half, at every birth, marriage or death, it is in constant demand. The well of all meaning: what we come from, search for, and return to: culture is the way that we learn to live with one another.

So let’s embrace one more hard truth: the flimsy vision of an independent state we sought in 2014 has receded from view and has become a vague memory of what might have been. But a country of independent people – who truly know themselves – is, and always was, the real prize.

good piece, best i gave read so far, perhaps because i came out rather than go ahead into the church in 1981 and i adore Scottish traditional music, stories, history: so the thought that Scotland could be a better fairer kinder greener nation that treasures its identity is what motivates me. Hope i am not wrong, very insightful and hopeful writing

I believe there is a disconnect between what you are saying and how you describe it. Let us assume a commonplace observation: that in British culture, for centuries, there has been ‘one law for the rich and another for the poor’, as the idiom says, double (really multiple) standards. And I recall a professor of queer studies on the You’re Dead to Me podcast saying they were ‘surprised’ to find in their researches that LGBTQ people in the British upper classes could be quite openly queer in the 19th century (‘eccentric’, maybe). The British imperial elite education system of single-sex residential schools and military colleges, combined with military recruitment at 16, seems to turn out a lot of the ruling elite to this pattern, closeted or not. I suspect this goes way back to dynastic politics.

Take another example of legal persecution: prostitution, where sex workers are punished but their clients are not (Silvia Federici is helpful in this area). Just because the ruling elite make something illegal doesn’t necessarily mean they want to eliminate it: sometimes driving something underground makes it easier to reproduce the power relations the elite desires, with lower class fearing prison or worse, upper class holding the whip hand.

Combine both, and I think a more realistic picture emerges of ever-fashionable British hypocrisy and cant. Military barracks doubling as brothels where the rich exploit the poor. Overseas parts of Empire where locals are exploited sexually by occupying militaries. The age-old link between male homosexuality and militarism (any military historian might tell you about ancient Greeks). Rape used as a weapon of war and terror. The reporting restrictions on the Falklands War. The recent trend of Internet videos of British sado-sexual military initiations typically involving that favourite, British officers in drag. The appalling stories of sexual abuse and bullying within the ranks of the military. Many suicides. The recorded propensity for sexual crimes, racism, sexism and violence by serving personnel and veterans. Past and ongoing inquiries. Elite and special forces culture. The recent RAF scandals and incidents. Military omertas and codes.

The picture is one of extremely unhealthy British military culture where traditions of relative impunity for crimes and abuses transmitted down the hierarchy foster the practice of upper class/higher rank/elite unit gay and bisexual males (and more recently females) exploiting lower class/ranks (who sometimes seem to internalise, join in, or go along with such practices), who were denied protection and redress, and indeed were likely to be punished if they reported it. This systematic abuse by LGBTQ people is inconvenient for those trying to push a narrative of an omni-persecuted ‘LGBTQ community’ and straight bullies. But we should attempt accurate histories over interest-group propaganda. Not least so that anyone considering joining the British military is adequately informed (a state no child will be in, I don’t doubt).

Beautifully written, Chris!

Yeah

Enjoyed reading that and get some of your insights.

I’m not sure if it fits with your “But a country of independent people – who truly know themselves – is, and always was, the real prize.”

Often called naive, my interest is in finding a route to, working towards, a more caring, fair, just and equitable society/world.

It has always (in my short life – 72 years) seemed to me that the politics of the so-called united kingdom are not interested in, and could not lead to, that. Indeed, could not even ‘work towards’ that.

While, by majority, Scotland’s people have always seemed more to the left and therefore interested in what I’m interested in. Of course, how can anyone be certain of that?

But independence seemed, still does, the best option. Here’s to independence asap, and to working towards a more caring, fair, just and equitable outcome.

@Sandy Watson, perhaps the stated ambitions of the Scottish government in responding to the Empire, Slavery and Scotland’s Museums steering group of independent experts ties both strands (self-knowledge and justice) together?

https://www.gov.scot/news/empire-slavery-and-scotlands-museums/

Although how this could be achieved without establishing a Truth Commission with statutory powers to access all archives and publish any document, I don’t know. UK Official Secrets remains possibly the best defence against such truth discovery.