a discourse of the common wheel

despair, despondency, failure, adversity, optimism and tough elastic polymeric substances — Paul Tritschler considers some bumps on the road

Two guys were doing tractor tyre flips across the campus green. It struck me as the kind of exercise Victorian prison governors would have welcomed into their punishment arsenal to discipline inmates and compel obedience. Equally, albeit on another plane of reality, I could see myself in one of those long-forgotten summers of the distant past among a dozen or so raggedy kids from our old tenement block, like ants around a sugar lump, rolling the giant tyre along the streets with one of us inside like a cartwheeling Vitruvian Man. Somehow the rubber ring ritual rolled into the public fitness realm, and it is indeed very public, a ceremony of sorts, far from the kind of exercise one does in a quiet corner of the gym, or in the privacy of one’s home or garage. Whilst the tyre flip might appear primitive, punitive and perhaps pointless, the two young blokes on the campus green seemed to derive immense pleasure from it, maybe even a sense of fulfilment. Their faces were bright red, glistening with sweat and evidently strained, but they were also smiling, and there were occasional high-pitched bursts of laughter, like the release of pent-up steam. The possibility of exhaustion-induced hysteria occurred to me, but it was more likely that they were put into a positive state of mind, perhaps a euphoric state, by a hyper-secretion of endorphins linked to exertion. The brain’s reward system, the inhibitory response to pain and the heightened feelings of well-being that follow, might explain why they repeatedly engaged in tyre-flipping behaviour, but there were other possible factors, and conceivably a combination of them.

Consciously or otherwise, their purpose in putting on this overt display of physical prowess, and of demonstrating the implicit attractiveness of muscular definition, could be viewed as an attempt to suggest to potential mates their survival value and reproductive fitness. From this perspective their efforts are simply reducible to a biological carrot-and-stick system, where the pleasure-seeking impetus masks the evolutionary drive to spread their genes, and ultimately the motivation to ensure species survival — a sort of built-in sex slavery, really. And then there were the varied strands dangling from the martyr complex to consider. Often suffering from feelings of low self-worth, and a related tendency towards anxiety and depression, the martyr seeks validation through self-sacrifice and suffering, and in so doing finds a means of self-expression. The martyr complex, the exaggerated need for recognition and acceptance, is prominent in the context of social media. Users who fall into this category, many of whom might be read as manipulative in their management of shame and guilt, tend to seek validation by laying bare their personal struggles to their online audience — especially the fact, as they see it, of being hard-done-by — and all this to appear noble, strong, virtuous, perhaps even superior as they publicly flip through the personal challenges of each day. There was, I thought, something of the ceremonial stunt that is tyre-flipping in the martyr complex: the need for recognition from an audience, the need to be seen struggling yet ultimately strong in the face of adversity; but it was a far from perfect fit, especially when we consider that there were two playing the game…though that might be considered a convenient veil.

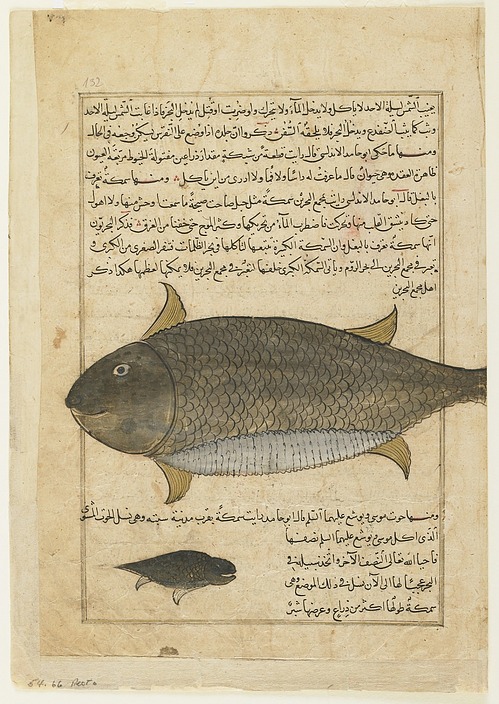

Chronic martyrdom, reproductive success, and mood-enhancing peptides apart, I wondered under what circumstances I might be drawn into this somewhat Sisyphean task. What if by divine intervention I were to be offered a last-minute reprieve from death by agreeing to flip this big rubber doughnut up and down a field for the remainder of my life. A dilemma, since this task, serving no purpose other than to perversely amuse the gods, would render life meaningless to the point of sharing an equivalence with death. That being said, the endless tyre flips might be just about bearable if I were one of a dozen others assigned to the task, which is an odd idea to conjure up given that I have never considered myself a team player, but an outsider, and have been so inclined since late childhood. From one perspective, perhaps, that is a dismal admission of interpersonal oddness, but from another it is simply to state that I have rarely in life stumbled upon a social group with which I might comfortably integrate; on the very few occasions when I have found a like-minded social circle, the members either died, or moved to distant shores, or both, though not necessarily in that order. As a result, not only do I seem destined to remain an outsider, I might also be a jinx. That being said, in an effort to gain for myself some element of equitability, it behoves me to borrow and bend a line from the seminal treatise of that great medieval Arabian cosmographer, Qazvini, who reminds us that among the unique wonders of creation, there exist singular oddities of existence.

Folio from a Aja’ib al-makhluqat (Wonders of Creation) by al-Qazvini

That’s a good thing, right?

The idea of the divine doughnut contingent intrigued me. I imagined the group could act like a stent to increase blood flow to the heart, to a dozen hearts beating as one. We might take turns flipping the big ugly thing, and give each other encouragement to get back up when we fell to our knees through exhaustion or despair; we might chant or sing songs to bond and lift spirits; traction might be gained through mutual trust, and friendship by the act of being locked in but pulling together, albeit in an entirely meaningless pursuit. Normally none of the above would appeal to me, but when the alternative is sudden death I imagined all this team spirit malarkey could take on a different meaning. It could indeed become a meditative and contemplative experience, and who knows what chambers of the mind might spring open, possibly taking us far from mundane social constructs such as time and dull everyday routines towards a separate and higher plane of existence. I began to see the doughnut as an ensō, that transcendental calligraphic symbol of zen and Japanese aesthetics symbolising strength, dhyāna, no-mind, the universe and enlightenment. It seemed perfect, almost.

On the other hand, the reverse might be true. Suddenly the pointless task became a fascinating if unethical social experiment bound within the parameters of my imagination. How long would we last as a complete and cohesive group, I wondered. To end the monotony one need only miss their turn to flip the wheel, and to drop out would of course be suicide, but who, if any, would choose that end, how soon might they decide enough is enough, and what might be the normative tipping point for the rest to follow. There may have been no hope for freedom among the galley slaves rowing the Viking ships until they dropped with exhaustion each day, but perhaps there was a vigorous and formidable sense of camaraderie deeply embedded within this powerful and efficient human engine, one that took them to a point beyond simple comprehension. Suicide seems to me a logical and far more attractive alternative, and I might be more inclined to drop my oar and make haste with my psychopomp into the afterlife, yet when isolation is taken out of the equation, I suspect the majority would choose pointlessness over nothingness, and maybe I would too. Maybe.

With my back turned to a group of students sitting an exam, I observed the strenuous efforts of the tyre-flip guys from the third floor of a building constructed almost entirely of glass, one that our chief maintenance man claimed was held together with Kleenex and spit. With my forehead pressed on folded forearms against the floor-to-ceiling window, as though in an act of abject surrender, I watched my breath materialise then evaporate on the glass, and in that short hypnotic timeframe the wheel rose and flipped, rose and flipped, further and further into the distance. The tranquil moment was interrupted by the catastrophic thought that if this Kleenex-and-spit-stuck window popped out I would plunge to my death, or worse. I flinched on seeing myself meet the ground among many shards of glass, and imagined the maintenance man standing over my haphazard heap, slowly shaking his head with some banal utterance from his store of unhygienic metaphors. I calculated the risk of surrendering to this absurd thought to be far greater than the act of challenging it, and so I leaned with all my weight against the window. Nothing happened, not even a creak.

This was not a manifestation of suicidal ideation, but simply an attempt to iron out the kinks: those cognitive distortions and irrational thoughts that buzz around like sand flies from time to time. And I was not alone. Just prior to the exam a student asked me to wish him luck. There are no tricks, traps or surprises, I assured him, adding that he didn’t need luck. Wish me luck anyway, he insisted, and I did. A couple of others chimed in with the same request, and after telling the class to open their papers and begin, I issued a class-wide good luck, though privately I thought it bad luck to do so. If they did well in the exam, and even if they didn’t, they might falsely attribute their results to luck rather than the degree of preparation and effort they invested. Fertile ground there for self-doubt and negative thought patterns. The student group had studied and been tested on those very areas of psychology in the course of our years together, but applying this learning to ourselves, flipping those heavy weights of self-doubt on our own, can be a different matter. I would undoubtedly revisit this issue before our forever goodbyes.

![]()

![]()

There were glass buildings all around the campus green, and at some point I became aware of the fact I was not alone in watching this rubber wheel upend and topple across the grass. Directly opposite there was a group of young men following the tyre flips with their eyes, a serious-faced solitary man with his hands in his trouser pockets watching from the floor above, and a group of young women from the floor below. No doubt others in the course of the afternoon had wandered over to their window and watched the tyre flip feat for a while before returning to their work. As I suspected, the tyre flip boys knew they had an audience, and I wondered what the onlookers wondered, but quickly dismissed the idea of circulating a questionnaire to compare impressions. A woman across the way sitting by her desk and angle-poise lamp gave me a little wave. I wiggled the fingers of my free hand, the other was pressed against the window and supporting my forehead. Though I never got the angle-poise woman’s name, I had spoken to her in the canteen once when sharing a table, and on that occasion talked at great length about French New Wave cinema, Godard and stuff, because I mistakenly thought she taught film and media. Probably because I was rambling on about films, she found a way to insert into the conversation the fact that she was a very close friend of the next door neighbour of the film actress Keira Knightley’s mum. I ran out of words, and have done again.

From the vantage point of my securely-fitted and recently-tested floor-to-ceiling window, the consistent efforts of the tyre boys across the campus green held my focus. Whilst one repeatedly flipped the tyre over to the end of the green, the other lessened the burden by encouraging him every step of the way. On reaching their destination they swapped round the back brace they used for lumbar support, and quickly switched roles, where the heavy lifter now became coach. But for the occasional and unmistakable sound of pages being turned and gently flattened out, the exam continued in silence, rendering it just possible to hear the raised voice of the coach in the distance — “Squat, grip the base, drive up with the legs, push up, up, up. Just a bit more. Well done! Now, again! You’re doing really well” Each covered the green several times, a length of perhaps one hundred yards, but I wondered just how much ground each might have covered in the absence of their mutual encouragement and acknowledgement, which together clearly served to build confidence and foster perseverance. It was a public demonstration of dynamic reciprocity between two actors, one pushing his body to the limits, the other pushing his mind and quelling his doubts. Whatever their motivation for doing tyre flips in this public arena — there are, after all, more discreet ways to work on muscle groups — it showed that sometimes we need to draw strength from the people around us. Indeed, sometimes we just need them to wish us luck if only for the gentle reminder, albeit in a very small way, that we are not alone.

The tyre-flip boys flipped on tirelessly. In considering those words it occurred to me that the American spelling of tyre has itself a flip side, from an inflated rubber wheel to a deflated human being. For some reason an ironic duality of meaning was imposed on this otherwise innocent monosyllabic appellation, and the tyre consequently wobbled into the province of semantic confusion. Needless to say, fiercely indignant pedants across the British Isles throw tantrums from time to time over the contemptuous mockery they believe is embedded in American language. I don’t think this is fair, nor historically accurate, but with orthographic rivalry in mind I wondered if there might exist a synonym for tyre that could quell the uncontrolled outbursts and satisfy all.

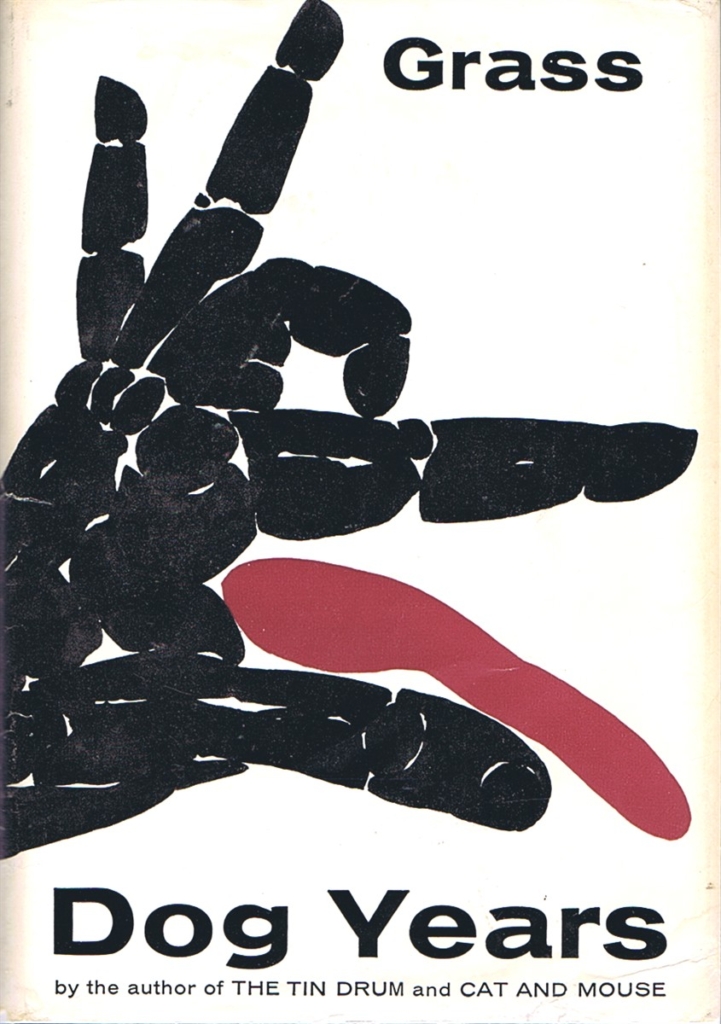

Unfortunately, there was absolutely nothing of relevance rattling around my neural network, nor was there much to be derived from my old and comforting friend, a soft but tough Collins dictionary. I’ve had this dictionary since 1970, always kept in my back pocket at school, and later when working as the assistant to the gardener’s labourer in the Royal Parks, where I remember I often consulted it behind the forsythias when reading Günter Grass’s Dog Years. Perhaps much is lost in translation from German to English, but I found Dog Years, the last in the so-called Danzig Trilogy, a difficult book to grasp at the time. The book’s style bears some resemblance to the contours of Heidegger’s Being and Time, which I also found difficult to read, though that was some years later. In any case, Dog Years helped me with Heidegger, and my small blue indestructible dictionary helped with Dog Years, but nothing helped with finding a suitable synonym for the rubber component of the common wheel.

With a measure of reluctance I turned to that all-powerful predictor of text and increasingly of thought, to that god who, using standardised communication protocols, fills heaven and earth with innovative applications of ambient intelligence — the internet. To my amazement, the simple search generated a lengthy and strangely disparate list of alternatives to scroll through, among them hurled, elevated, thoth, thrush and threshold, a term for three-point shots in basketball, and a unit of language pertaining to the sum of oxides in heavy rare earth elements (I deeply regret the time wasted wandering down that rabbit hole). It was only once tragedy struck, offered almost mockingly as a possible word option, that I at last revisited my query and discovered I had not in fact requested an alternative to tyre, but to thre. A minor typographical error, yet for a moment I felt stupid, and heard myself muttering some self-deprecating words under my breath.

I wondered how often thoughts lacking a valid pass slipped through the consciousness barrier, slowly and insidiously piling up like tangled string in the dark corners of my cerebral vaults. And I thought about times past, my teen years in particular, when I rarely gave myself a break, lacking the ability as yet to talk to myself effectively, to identify and reframe the kind of thoughts that can chip away at one’s sense of worth as a human being. Not that I was always staring down my socks, but there was a time when I felt drawn to a fairly pessimistic narrative. Indeed, for years I gave the parasite that thrives on pessimism, and its corollary, self-doubt, rent-free accommodation in my head. This resulted in a sizeable accumulation of wasted opportunities, some so rare that I still kick myself, and occasionally others join in. In time, through persistent effort and vigorous disputes, I served the unwelcome tenant an eviction notice, but it still roams around the neighbourhood, and occasionally I catch a glimpse of it lurking in the shadows, ready to ambush in moments of vulnerability, moments such as that prompted by thre.

Pessimism is a common companion to depression, but it sometimes gives us a better view of reality, and as such it would hardly be wise to try to eliminate it entirely. From an evolutionary point of view, we are wired to consider the dark side, just as we are wired to gorge ourselves on sugars and fats; both are necessary for our survival, so long as we are in control. In order to make decisions that are balanced with regard to risk and opportunity in everyday life, it is of benefit, I think, to leave room in one’s mind for an element of pessimistic thinking, however bleak that may seem. Facing the sudden prospect of an electrical storm, for example, I suspect passengers would prefer a cautious pessimist piloting their aircraft over the mountains to that of a gushy and unbridled optimist. In the same way, the optimist might imagine having the body of a Greek god at the end of an excessive and undisciplined tyre-flipping exercise, but the pessimist offers the more realistic prospect of an inguinal hernia. In truth, however, such examples are essentially battles of syllogistic reasoning, often common sense, dressed up as a war between popular but vague notions of optimism and pessimism.

When grounded in logic, rational thought and balanced decision-making, optimism is merely the perfectly justified and evenly distributed explanatory style of a more contented individual. In particular, optimism forms a frontline psychological barrier against negative thought patterns, those irrational thoughts that prevent people from living more fulfilling lives, and in some cases ends them. As such, it is inseparable from the notion of self-care and self-compassion, but it requires a conscious effort to be developed as an evidence-based habit in our everyday lives. We do this by reflecting on our thoughts, challenging them, and demanding a reasoned justification for why we should think what we think. In this way optimism prevents us from being trapped in cycles of despair, prevents us from feeling discouraged after experiencing a personal defeat, prevents us from thinking of ourselves as a failure and thereby sliding into feelings of ever-diminishing self-worth. It is like fighting a mind virus, but in reversing our habits it’s not always easy to go it alone. To identify the pathogens and filter them out we may need help. As was evident with the tyre flip boys, other people are often an important ingredient in the mix.

There are not always grounds for optimism, but the key is to check the evidence before passing sentence on ourselves, or indeed others. If it is essential that we apply this principle to our everyday lives, it is important that we apply it to the lives of those with whom we interact — spreading goodwill nourishes us all. It hardly needs to be said that we don’t have to be suffering from bouts of depression or be plagued by pessimism and self doubt in order to seek improvement in our lives. The guys on the green didn’t have to do tyre flips to get fit, they were already there. The exercise was simply a means to improve on their fitness and sense of well-being, and perhaps there were other heights to which they aspired. There is after all no limit to quality, no ceiling on what we might achieve, relative to our potential, but we can’t know what our potential is, and what realistic expectations we should set for ourselves, unless we develop a means to eliminate all the encumbrances, and to thereafter keep our guard up. To put it another way, we can’t be free unless we question what it is that puts us in constraint.

Optimism is a reasoned philosophy and a way of being, and as such it branches into all the areas that we care about, and should care about, including our politics. Especially our politics. It is, after all, key to our capacity for change, and change begins at the level of the individual.

Please donate & share:

Backing Bella Caledonia 2025 – a Creative & Arts crowdfunding project

I’m confused. Why is there no mention of Robin McAlpine in this?

lols

Brilliant read.

Better than any remedy pill.

Way to go.

Presumably Socrates, as an example of a non-academic philosopher, would have simply asked the two guys what they were up to.