Cosmonauts and Stale Porridge, Alexander Trocchi’s Influence on Radical Scottish Media

Cosmonauts and Stale Porridge, Alexander Trocchi’s Influence on Radical Scottish Media, exploring Scotland’s radical publishing traditions. This is adapted from a talk at the Trocchi at 100 event in the Kelvinhall Glasgow organised by the Department of Scottish Literature at Glasgow University and the Andrew Hook Centre for American Studies.

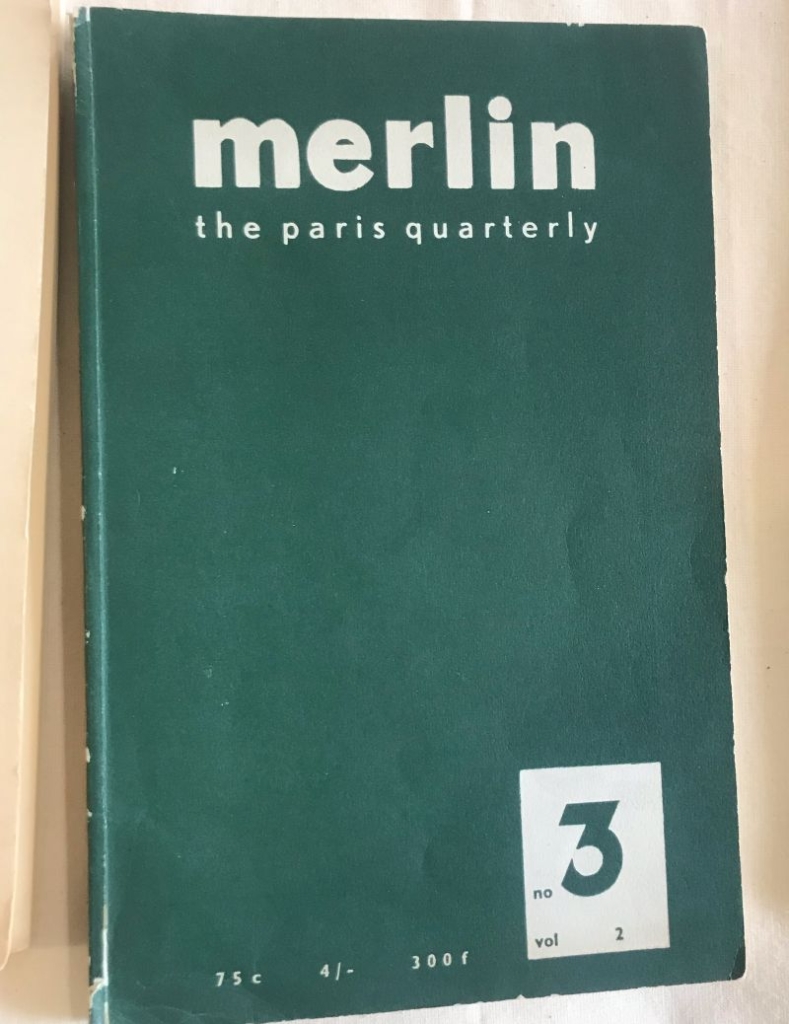

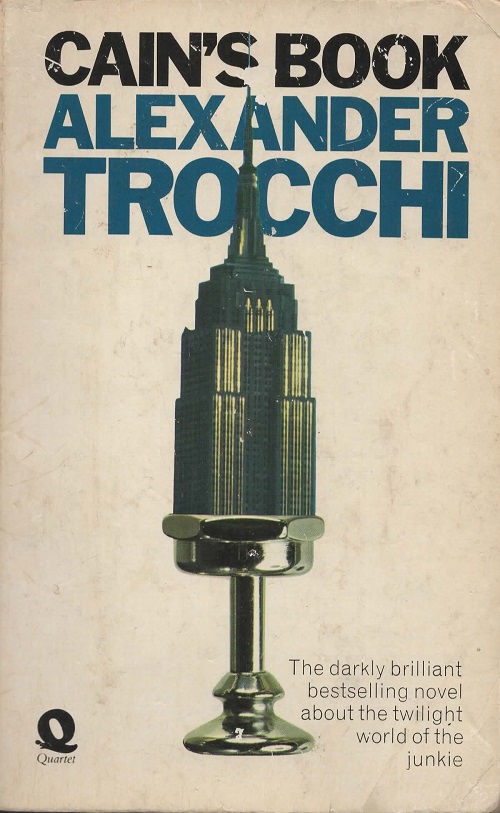

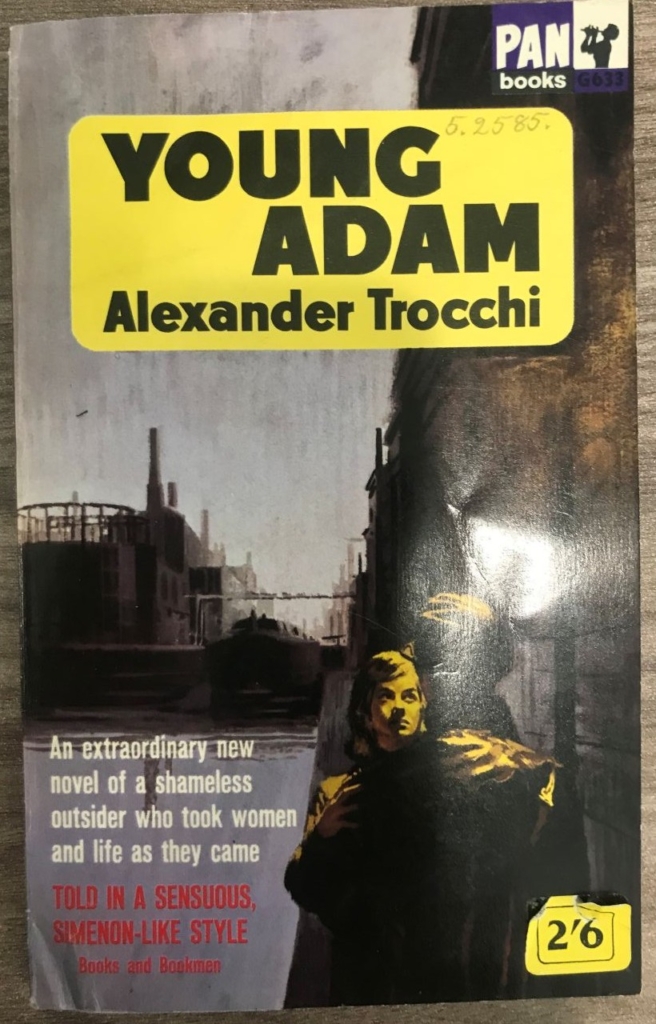

The Glasgow-born writer Alexander Trocchi, author of Cain’s Book and Young Adam, edited the literary magazine Merlin in Paris from 1952 to 1954. It published many leading writers of the time such as Samuel Beckett, Henry Miller, Pablo Neruda and Jean-Paul Sartre. Through his expansive editorial ideas in Merlin and such projects such as the Sigma Portfolio; the seminal essay The Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds (1963), and the Moving Times magazine proved to be a benchmark and a point of inspiration for a decade and more of literary culture and magazine editing. Trocchi’s ideas would influence editors such as Alex Neish and Bill McArthur as well as key cultural activists such as Kenneth White, Tom McGrath and RD Laing, amongst others, bringing radical ideas of Situationism, bohemianism and Beat Poetry directly into Scottish culture.

Scottish radical traditions have been airbrushed out of history. It’s what Professor Murdo MacDonald has called ‘mislaid history’, but also speaks to a form of inferiorism, a lack of understanding of Scottish traditions of thinking and the distinct political history of ideas. Re-examining the threads of Alexander Trocchi’s influence on culture, publishing and radical politics is an antidote to this process of erasure. This talk places Trocchi in historical and political context and explores the milieu of radical publishing he influenced. In doing so, it seeks to reimagine Trocchi not as ‘other’ as part of a contrived ‘split’ in Scottish literary and political culture between a ‘pure’ Scottish tradition, exemplified by MacDiarmid, but as an essential and important part of a wider culture.

EPSON MFP image

THE ANTI-RENAISSANCE

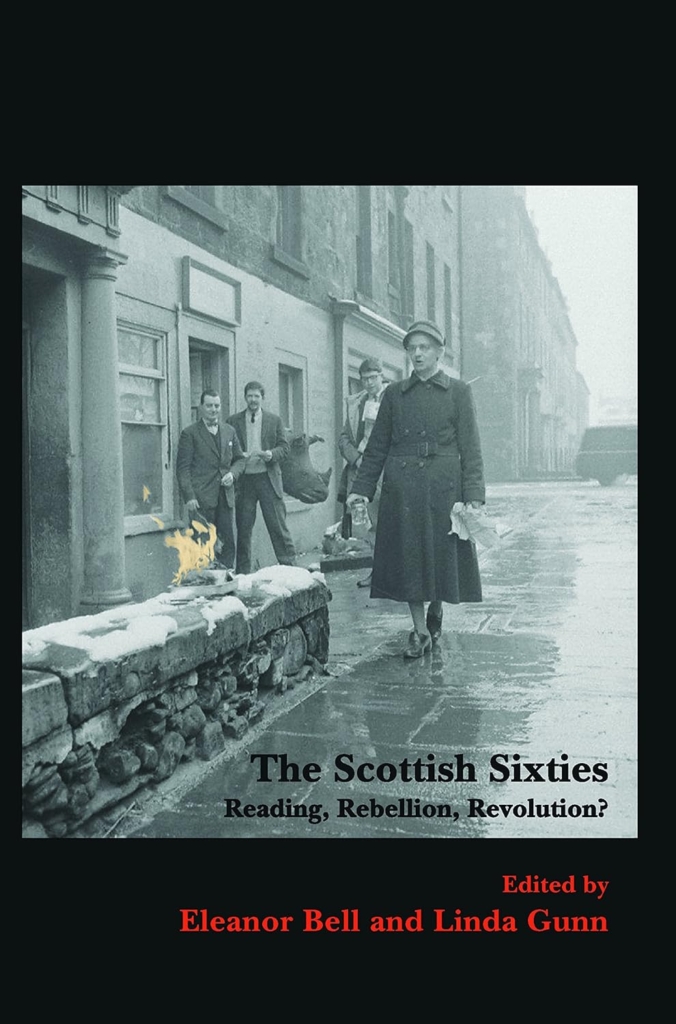

As Sylvia Bryce-Wunder writes in The Scottish Sixties edited by Eleanor Bell and Linda Gunn (Through Expatriate Eyes: Muriel Spark, Alexander Trocchi, and the Empowerment of Scottish Literature during the 1960s):

“Scottish Literature benefited from and contributed to the revolutionary and experimental spirit of the 1960s. Many Scottish writers during this period challenged the nationalistic approach to literary representations of Scottish culture, experience, and identity.”

She goes on:

“Unlike some members of the Scottish Literary Renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s– such as Lewis Grassic Gibbon, James Barke, George Blake, andHugh MacDiarmid – many writers of what Maurice Lindsay termed the ‘anti-Renaissance’ of the 1960s disputed the nationalistic approach to the representation of Scottish culture, experience and identity. The problematic representations of ‘Scottishness’ in the fiction of Muriel Spark, Alexander Trocchi, Robin Jenkins, William McIlvanney and Archie Hind – to name a few authors who were active during the 1960s – contributed to a cultural paradigm shift by challenging the purist, hyper-nationalistic and insular values of the previously dominant discourse of Renaissance writers. Two writers in particular –Alexander Trocchi and Muriel Spark – exemplify the questioning spirit of the decade and challenge rigid notions of Scottish identity throughout their novels and non-fictional works. More than many other Scottish novelists of the 1960s, the itinerant Trocchi and Spark transcend the real and imagined borders of Scotland in their writing.”

Sylvia Bryce-Wunder concludes: “Alexander Trocchi struck a controversial chord during an already turbulent time in Scottish literary development, alienated himself from many members of the Scottish literary establishment, and was one of the most influential Scottish writers of the ‘anti-Renaissance’ era…Spark and Trocchi – with their independent, critical approaches to Scottish writing – empowered Scottish Literature by challenging the limitations imposed by the Scottish Literary Renaissance of the inter-war years.”

It’s noted that Scotland has a problem with institutional memory loss. Our literary and political timeline is marked with endless periods of ‘renaissance’ and ‘revivals’ as generations discover and re-discover fragments of important cultural history. Trocchi himself underwent ‘revival’ when his work (Young Adam and Helen and Desire) was re-published by Rebel Inc in the early 1990s. Rebel Inc (the magazine) can thereby be seen as part of the Trocchi publishing influence/legacy. I’d argue that this institutional memory loss is because our cultural institutions either do not exist at all or do not consider ‘us’ important.

Stewart Home has called poetry the ‘Heavy Artillery of the Cultural Revolution’ and attempts (and fails) to portray Trocchi as primarily a poet in the Afterword of Trocchis collection Man at Leisure, but for the purposes of this talk I’ll be considering his influence as an editor, and what is now excruciatingly called ‘an influencer’.

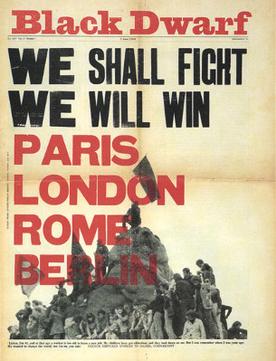

UNDERGROUND MEDIA

The period 1955 – 1975 gave birth to the idea of an alternative press, it gave us literary journals such as Merlin and political publications such as Peace News and International Times (edited by Tom McGrath) and the Black Dwarf, all part of what William Burroughs called the Underground Media.

We can see the trajectory of Trocchi’s contribution spanning from the fifties to the Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds (1963), to the Moving Times newsheet of Project Sigma to the Albert Hall on 11 June 1965, for the international Poetry Incarnation aka “Wholly Communion” with seven thousand punters through to the London Arts Lab party of April 1969 that was billed as “Alex Trocchi’s State Of Revolt” with Trocchi, William Burroughs, R. D. Laing and Davy Graham. According to Drs Angela Bartie and Eleanor Bell: “the 1962 International Writers Conference is now viewed by some as the starting point for many of the subsequent large gatherings and conferences (eg the Albert Hall poetry reading of 1965, which characterised the counterculture in sixties Britain) and even the existence of the major book festivals that we have today.”

The State of Revolt is widely seen as the death-knell of the sixties psychedelic scene, as the movement slumped into drug-addled chaos. Trocchi’s contribution is contested, but here we can see a Glaswegian writer at the very heart of the radical European avant-garde and acting as a bridge across the Atlantic.

Tom McGrath read at the Albert Hall with Allen Ginsberg and became features editor of Peace Times and then founding editor of the seminal British underground journal International Times. He was instrumental in the founding of Glasgow’s Third Eye Centre in Sauchiehall Street, now the Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA), and was director from 1974-77. In the early 1980s, McGrath supported the founding of the Glasgow Theatre Club at the Tron, which became the Tron Theatre. So some key platforms for Scottish cultural revival, the Traverse, the CCA, the Tron are all deeply rooted in Scottish connections to the 60s avant-garde.

Radical publishing would go hand in hand with theatre as bohemian Edinburgh emerged around the Paperback Bookshop owned by Jim Haynes. The shop had been at the heart of the controversy of the publishing by Penguin Books of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960. Haynes would go on to co-found the Traverse with Richard Demarco in 1963.

In 1968, an Edinburgh PhD student called Bob Tait, then an editor of the student-run Feedback magazine established Scottish International Review (SI) with support from the Scottish Arts Council. The lineage of John Holloway and Richard Gunn’s Common Sense journal, the publishing of Gramsci via Hamish Henderson and the emergence of the sort of platforms that would give space to Variant, Calgacus, Harpies & Quines, or Radical Scotland amongst many others have their backstory here.

You couldn’t have had Chomsky in Govan without Trocchi in Edinburgh. Nor would you have had Allan Ginsberg in Scotland without this tradition and without this cultural energy.

It’s noticeable that the famous Self-Determination and Power event at the Pearce Institute in Govan, Glasgow in January 1990 featuring Noam Chomsky was organised by a loose alliance of the Free University of Glasgow, the Edinburgh Review, then under the editorship of Peter Kravitz, and Scottish Child magazine, edited by Rosemary Milne.

From publishing houses and formats. to literary journals and reviews, this era gave the very notion of a radical alternative press connected to an avant-garde its first breath.

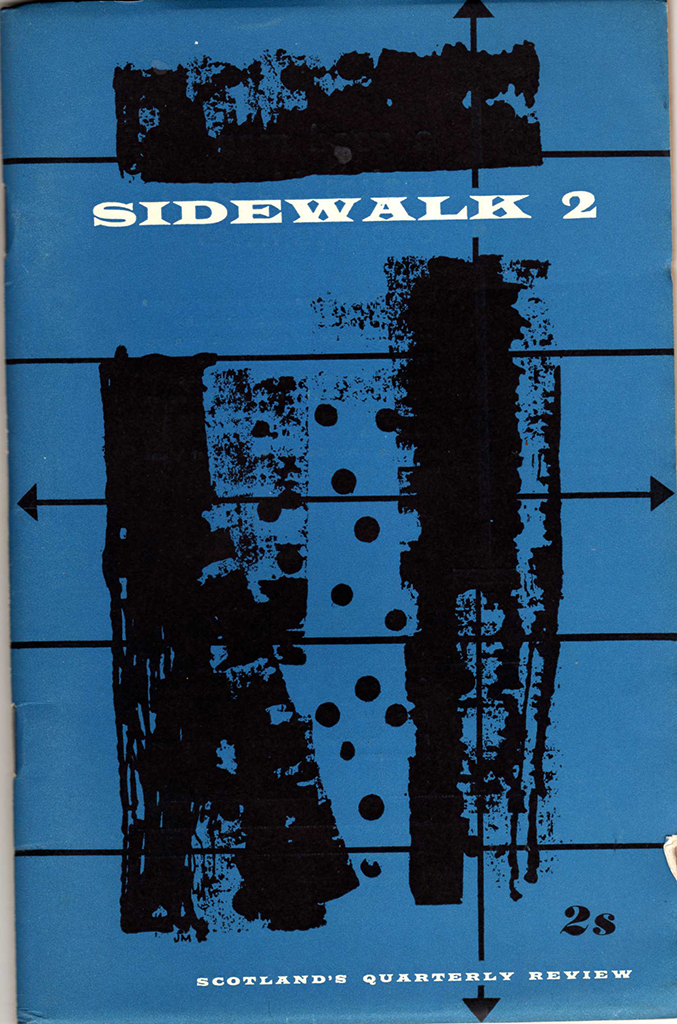

Three other magazines are worth considering in this lineage: Jabberwock, Sidewalk and Cleft.

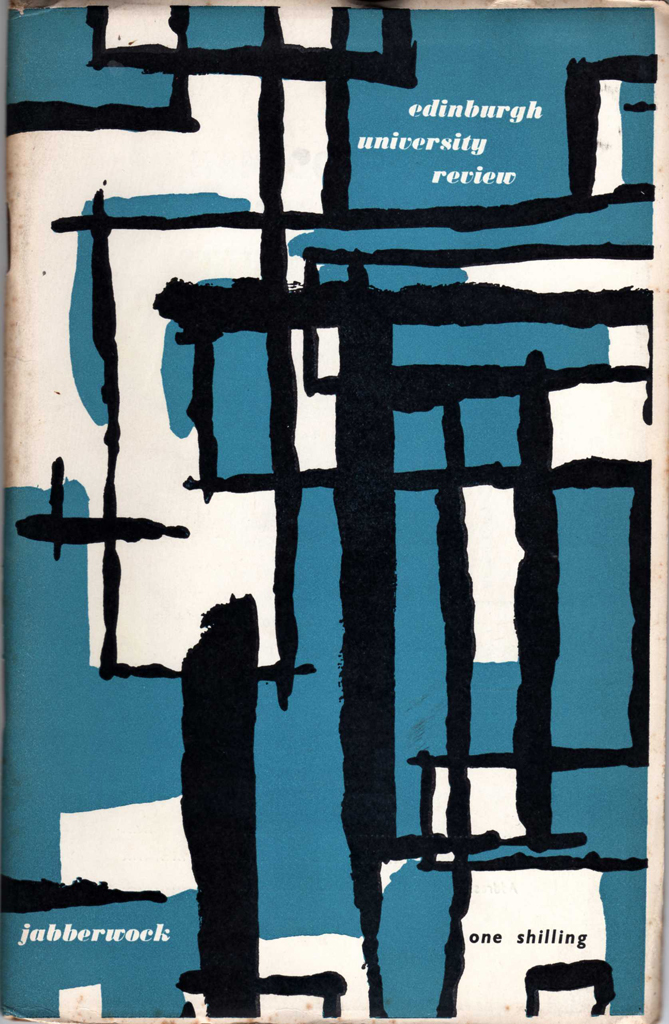

JABBERWOCK

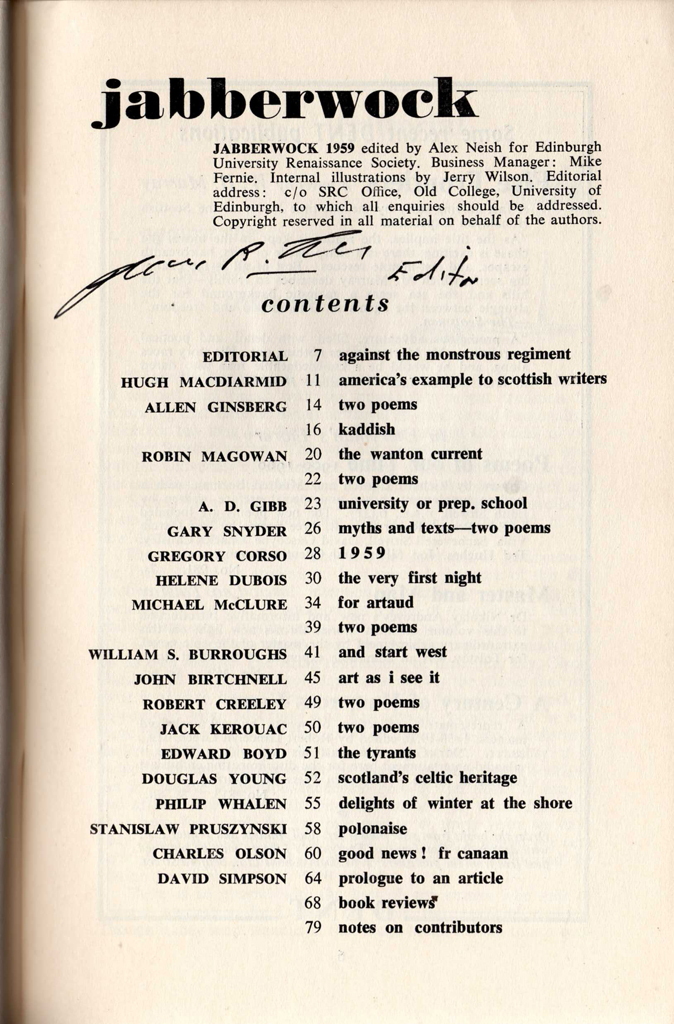

Jabberwock was edited by Alex Neish, a friend of Trocchi’s, who also edited the pioneering magazine Sidewalk which published the likes of Christopher Logue, Iain Crichton Smith, Iain Hamilton Finlay, Allen Ginsberg, Edwin Morgan, Gary Snyder, Helen Dubois, Hugh MacDiarmid, William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, amongst others.

Neish was a Scotsman who put out an issue of the Edinburgh University Review entitled Jabberwock in 1959 with the superb first chapter of Naked Lunch in it: ‘And Start West’.

In an interview with Neish in 2018 he said:

“Jabberwock was an introspective political and literary magazine that had been going irregularly since the early 1950s. In the late 50s and early 60s I formed part of a small group that ran all the student publications and was asked to take it over. I edited around 4 issues before deciding to do the American issue in Autumn 1959. This effectively killed it off and then led to Sidewalk.”

Asked what was the state of Scottish writing at that time? He replied:

“It was very introverted. Trocchi had not been recognised as the most important writer of the last 50 years — nobody had shown such ability since Lewis Grassic Gibbon in a completely different context. Scottish literature was still in the mists and for minorities. I still find it amazing that I was living in Edinburgh at the same time as that genius Sorley MacLean and knew nothing about him. He was not recognised in Scottish Renaissance circles which just about sums up their vision.”

Asked how he had met Trocchi, he replied:

“We were very friendly with John Calder and his then wife Bettina and when visiting London would stay with them. A frequent guest was Samuel Beckett who was charming and ordinary — and had a great fascination with bicycles. I persuaded John to publish Robert Creeley and then Alexander Trocchi whom we had met in Edinburgh after he jumped bail (financed by Norman Mailer who agreed) and escaped to Canada where he caught a fishing boat to Aberdeen. This was Cold Turkey. He stayed with us in our Edinburgh flat but soon was back on drugs and destroying himself. Before that once we went out to Milne’s Bar where MacDiarmid was holding court. I introduced Trocchi to him and the hostility was immediate. MacDiarmid as always had too much to drink, had never read anything by Trocchi, and soon was calling him “an illiterate cunt.” Trocchi looked down at him and said simply “You have a peculiar sense of gender.”

SIDEWALK

Jabberwock morphed into Sidewalk as Neish leaned into the American influence. From Burroughs and Scotland Jed Birmingham writes:

“Sidewalk created quite a stir and was part of a larger cultural phenomenon happening in Scotland. In the early 1960s, Scottish culture was incredibly provincial as was Scottish literature. Poets and writers often wrote in Scottish dialect and dealt in age-old Scottish themes handed down from Robert Burns. Social class and authority were respected and protected. Scottish poet Edwin Morgan appeared in Sidewalk 2. Morgan was one of the major forces in Scottish poetry and literary innovation. In a talk on the Scottish Left, he describes the swirl of activity happening in Scotland at the time of Burroughs’ arrival in London and thereafter.”

Edwin Morgan (who had taught Trocchi at Glasgow University and would go on later to become Scotland’s first Makar, states:

“In the Sixties, there was an atmosphere, an excitement, a sense of liberation, of potentialities, of boundaries being crossed, which came from a great variety of things outside Scotland — the music of Bob Dylan and the Beatles, a new explosion of poetry and prose in America with Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, a new generation of poets in Russia with Yevtushenko and Voznesensky, the beginnings of space exploration, the international growth off the idea of a counter-culture. All this was reflected in Scotland, to the surprise of not a few observers.”

At the heart of much of this was the vexed issue of censorship as writers explored and reflected the sexual revolution and tested the boundaries of conservative and presbyterian Scotland.

The editorial comment to Sidewalk sheds some light on why Burroughs was included in the magazine. In 1960, Scottish postal authorities seized a copy of Francis Pollini’s Night published by Olympia Press. The book was burned and poet Hugh MacDiarmid was questioned (the book was sent to him in the mail) by police.

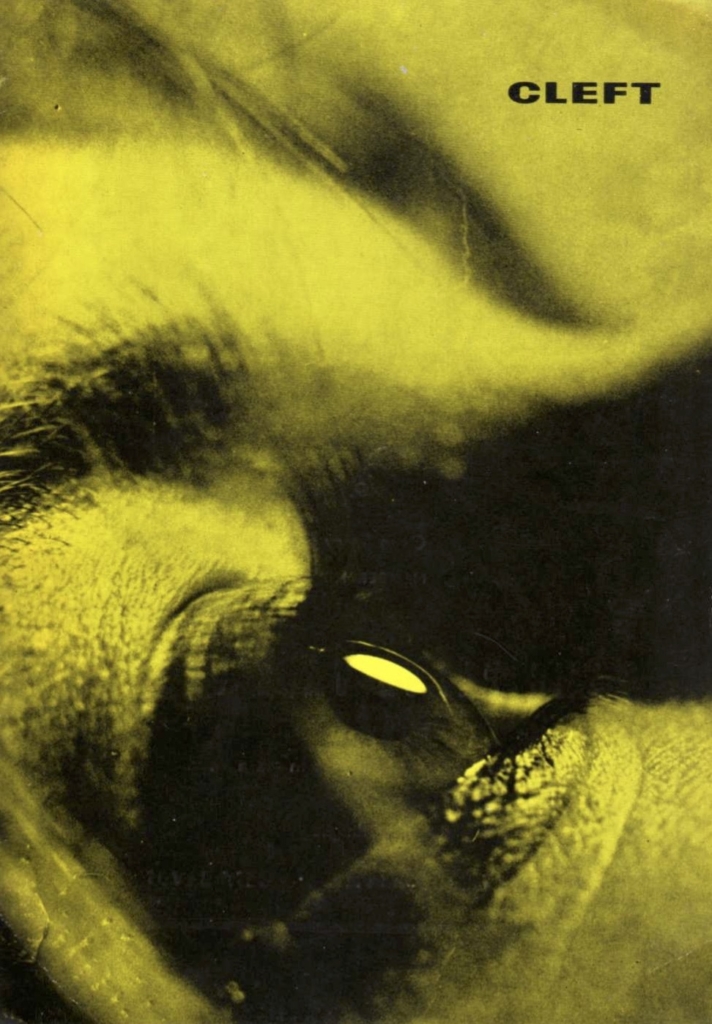

CLEFT

Edited by Bill McArthur, download available here.

As Jed Birmingham has written: “In the mid-1960s, Burroughs continued to be featured in the Scottish literary scene. In 1963-1964 in Cleft issues 1 and 2, Burroughs appeared alongside Norman Mailer, Henry Miller, and Hugh MacDiarmid showing the influence of the Writers Conference two years before.”

Scotsman Bill McCarthur started Cleft after University opposition to what had been published in the magazine Gambit.

Jed Birmingham writes: “Gambit published “The Mayan Caper” in Spring 1963. The theme of radical youth self-publishing morally and technically challenging literature continued in Edinburgh. The story of Big Table, New Departures, and Cleft highlight the slow rise of the youth culture in the late 1950s and early 1960s that would reach full bloom with the flower children, the Summer of Love and Woodstock Nation. Even in the silent decade, radical students existed or were being awakened. These battles against censorship and the fight for freedom of speech/press foreshadowed student movements like the Students for a Democratic Society, the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley, and student protest and University occupations throughout the West.”

Issue 1 featured Kenneth White, ‘Four Poems’ by Norman Mailer, The Motor Show by Eugene Ionesco, Martins Folly by William Burroughs, Three Poems by Andrei Vosnesensky (translated by Edwin Morgan), The Poet We Hope for by Hugh MacDiarmid, Same Rain by Astrid Gillis (a woman!), and Leaving for Buenos Aires by Alex Neish (!)

SCOTTISH LINEAGE

We can begin to see the outline here of Trocchi’s influence over literary and political culture in Scotland,

Writing for Bella in 2018 Jed Birmingham states:

“Through example, Trocchi lead a fight against Scottish tradition and became a figurehead of the international avant-garde. Trocchi showed Scotland that great and meaningful literature could step outside national borders and literary boundaries.”

I think this is only partially right. Certainly, Trocchi invites us to be of the world not just of the nation, to be wild and utopian. But he is as much part of Scotland’s rich cultural heritage as MacDiarmid is. Although often estranged from Scotland, the impact of Scotland on Trocchi and Trocchi on Scotland should not be erased.

One of the key figures in this trajectory is Kenneth White, who contributed to the Sigma Portfolio and went on to establish his ideas around Geopoetics. Norman Bissell has written: “White was one of five writers in Scotland to whom the Scottish writer Alexander Trocchi wrote proposing to set up a network to create ‘an Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds’. The others were Edwin Morgan, Tom McGrath, Hugh MacDiarmid and Ian Hamilton Finlay. The Jargon Papers were a couple of roneo sheets signed K.W. which were distributed in Glasgow. Jargon Paper no.1 was included in the Sigma Portfolio, a huge A2 sheet which Trocchi sent to his many worldwide contacts.”

He and White both spoke of the need for cultural revolution. Trocchi said in the Sigma Portfolio:

cultural revolt must seize the grids of expression and the powerhouses of the mind. Intelligence must become self-conscious, realize its own power, and, on a global scale, transcending functions that are no longer appropriate, dare to exercise it. History will not overthrow national governments: it will outflank them.

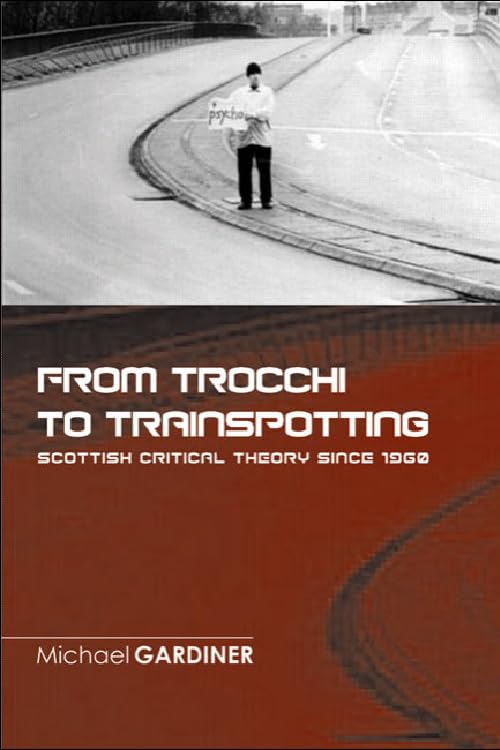

Michael Gardiner gave a detailed account of the Sigma Portfolio, and of White’s significance in terms of Scottish critical theory, in his book From Trocchi to Trainspotting Scottish Critical Theory Since 1960 which came out in 2006.

In it, he says:

“White has probably been the most determined scholar of intellectual crossovers between Scotland and France. One stress is that unlike over-specialised Anglo-Britain, France resembles the Scottish democratic intellectual ideal in that ‘in France… the general cultural question was always posed.”

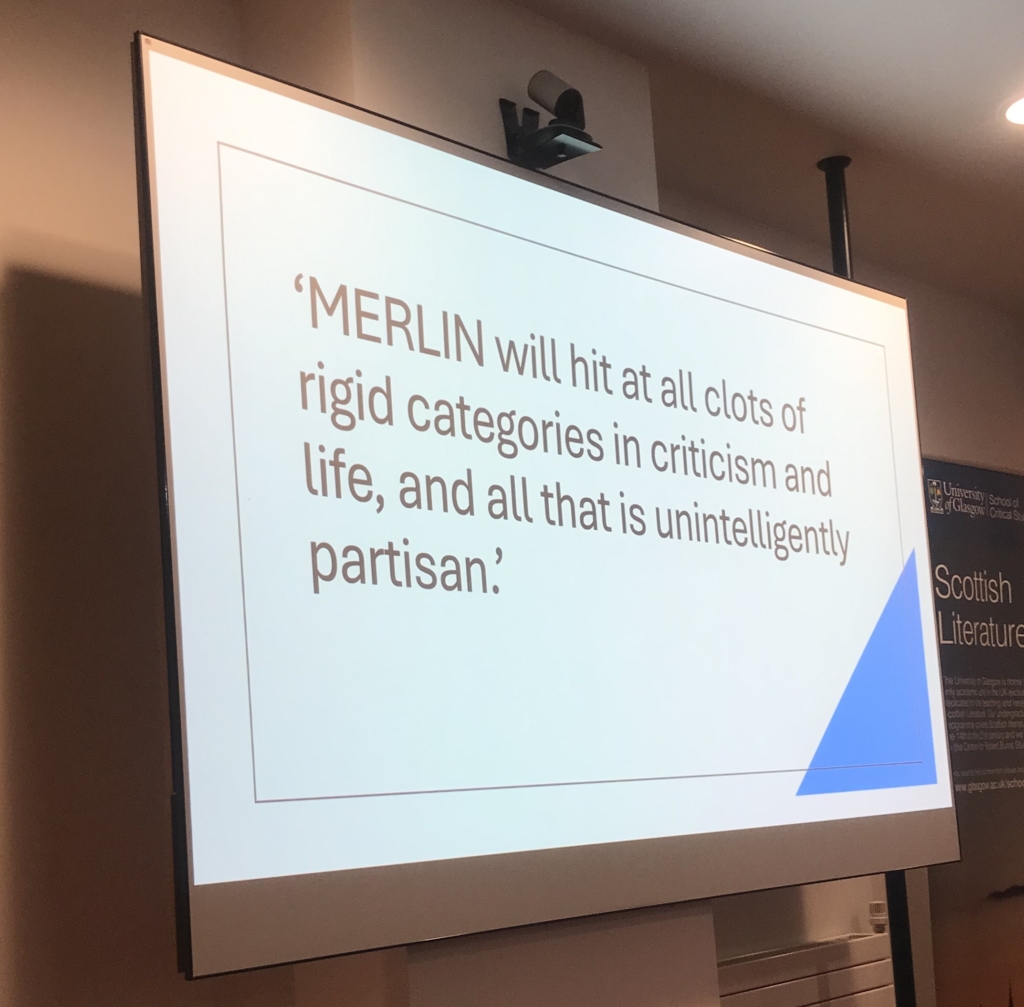

This is a key point. Writers like Trocchi, MacDiarmid and Alasdair Gray have radically different styles, perspectives and intentions, but they also have some common ground. If for MacDiarmid “Watertight compartments are useful only for sinking ships” and for Gray the task was to “Gather all rays of culture into one” for Trocchi “Merlin will hit at all clots of rigid categories in criticism and life”.

This is Trocchi, drawing on and influenced by the Scottish Generalist Tradition of which he is part.

Gardiner’s book “places within a wider theoretical context writers such as Muriel Spark, Edwin Morgan, Ian Hamilton Finlay, James Kelman, Alexander Trocchi, Janice Galloway, Alan Warner and Irvine Welsh, as well as more recent work by Alan Riach and Pat Kane, who can be seen to take the ‘post-Enlightenment’ narrative forward. In doing so, it draws on the work of the Scottish thinkers John Macmurray and R.D. Laing as well as the continental philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Paul Virilio.”

Sigma and the Invisible Insurrection

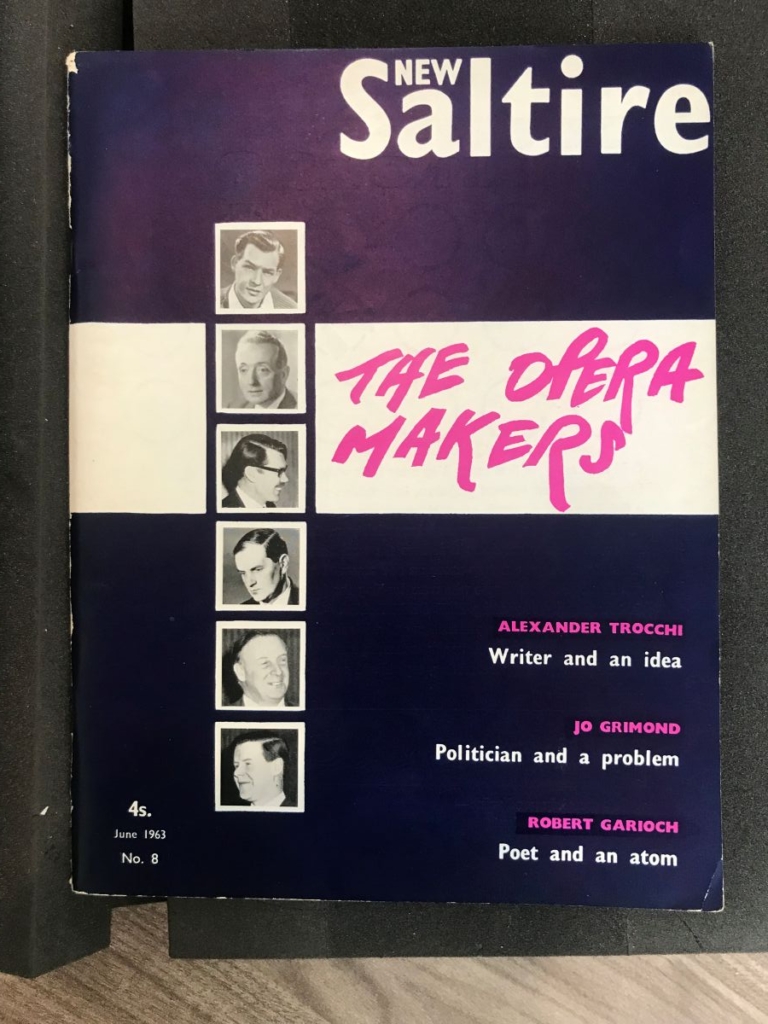

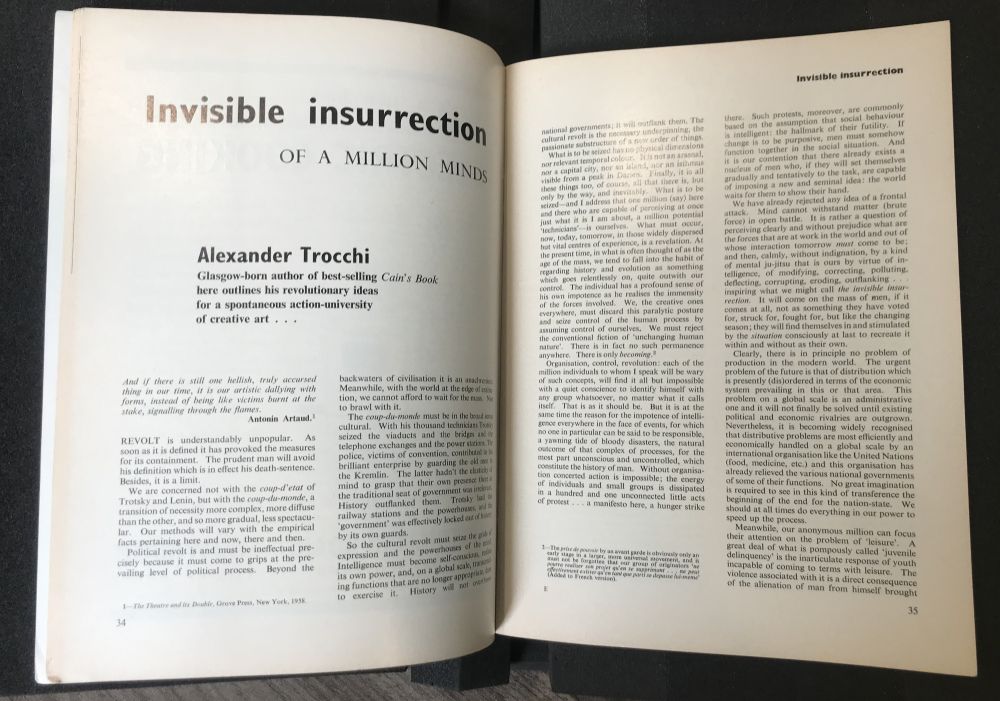

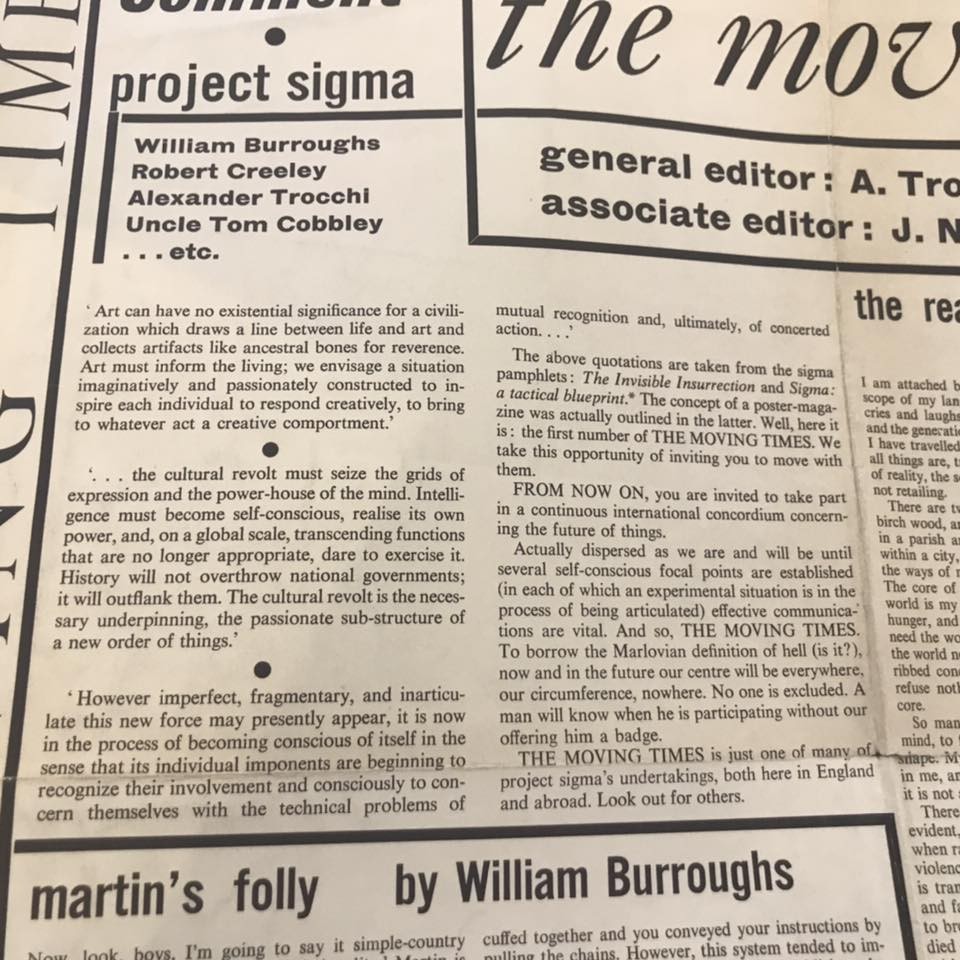

Trocchi’s seminal essay The Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds, was an integral part of the Sigma Portfolio (sp) and was first published in the New Saltire in Edinburgh in June 1963.

It would subsequently be published in France, England and America in International Situationist (Paris), Anarchy (London) and Architectural Association Journal (London) and City Lights (San Francisco). This is No 2 in the Sigma Portfolio. Amongst his ideas developed here is the idea of the “spontaneous university” a fertile and experimental ambience designed to equip people with those inner resources without which they will be unable to contend with LEISURE … a dominant fact of the future.

It’s telling that Trocchi first published the Invisible Insurrection in Scotland before publishing it in France, America and England. It’s worth looking over some of the other content in the Sigma Portfolio.

The ideas of the Invisible Insurrection were followed and fleshed out by s.p No 3 – Sigma: a Tactical Blueprint.

s.p No 4 is an essay entitled Potlatch (a term used by the Letteristes in Paris in the 1950s).

s.p No 5 – Sigma: General Information (August 1964). Collectively with nos 2,3 & 4 lays out the ideas. In this essay it deals with:

- What is project sigma?

- Its historical necessity

- The basic attitude and the technique of the “happening”: “an existential situation in which the protagonists adopt a metacategorical posture and play at discovering themselves, together, at leisure, freedom unrestricted by external constraints”.

- The global nature of the problem and solution; various situational techniques: the “box-office”.

- The use of hallucinogens, particularly cannabis

s.p No 6 is by RD Laing and was delivered at the 6th International Congress for Psychotherapy in London (August 1964).

Sigma notes it: “seems to Dr Laing, as well as to us, to be precisely sigmatic in its approach.”

Dr Laing’s statement that “we are all implicated in this state of affairs of alienation” calls for a therapeutic situation closely resembling the experimental ambience of Trochii’s “spontaneous university”.

s.p No 7 is listed as a “supplement to the Moving Times” – its a response to the coverage by the Scottish press to the poetry conference at the Fringe in August 1964:

“The conference took place in spite of the Festival Authorities: a bold, loyal, successful “holding operation” sustained almost entirely by Mr Haynes of the Traverse Theatre”.

sp 11 is a broadsheet produced by Joan Littlewood in collaboration with the architect Cedric Price.

sp 12 is a subscription form:

“The sigma portfolio is an entirely new dimension in publishing, through which the writer reaches his public immediately, outflanking the traditional trap of publishing-house policy and by the means of which the reader gets it, so to speak, “hot” from the writers pen. In a sense you might be subscribing to an encyclopedia in the making.”

This is a key point because Trocchi was advocating endlessly iterative self-publishing, a radical innovation in approach to dialogue and an open – global – invitation to participation. Other innovations can seen in the large format ‘poster-magazine’ of the Moving Times [see below] which they attempted to have posted throughout the London underground.

sp 13 by Marcus Field “sigma communications inaugural meeting of Mr John Calders Writers Night at Better Books (Nov 1964) The Moving Times special supplement

sp 14 is a sort of list or index of what’s been published so far.

sp 17 is a list of ‘people interested’ these include William Burroughs, Anthony Burgess, David Cooper, Anne Fletcher (Better Books), Allen Ginsberg, Jim Haynes, RD Laing, Timothy Leary, Tom McGrath, Ann Quin, Rosemary Tonks, Kenneth White.

sp 18 is the Manifesto Situationist sigma edition authored by Philip Green and Trocchi

sp 19 is an exchange of letters between Trochhi and Stan Brakhage (Nov 1964) where he uses again this term “historigem”:

“As we have said in another place, the “portfolio” is to be regarded as a continuous historical historigem”.

sp 21 is an essay by Michael McClure on the meaning of Revolt.

Sp 22 is a catchup and re-statement: “It cannot be repeated too often that sigma “does not exist”

sp 23 is Jargon Paper No 1 by Kenneth White it was read by the author to the Jargon Society in Glasgow Dec 1964

sp 28 is the Castalia Foundation – experimental workshops

sp 77 is titled Pool Cosmonaut and plays with the idea of the ‘ghost mob’ and our ‘tentative optimism’

Schisms and Unity: Leaving Scotland (and Coming Back)

A key moment in all of this was the 1962 International Writers Conference and the exchange between Alexander Trocchi and Hugh MacDiarmid. But in memorialising this moment we have lost context and been reduced to the classic fallacy of the divided Scotland (Highland/Lowland, Urban/Rural, Jeckyll/Hyde etc etc) and it is worth re-visiting.

In the discussion on day two ‘Scottish Writing Today’ Trocchi famously states that he was right to leave Scotland. The whole atmosphere “seems to me to be turgid, petty, provincial, the stale porridge, Bible class nonsense.”

MacDiarmid, whom he has a ‘certain love and respect for’, is nonetheless ‘an old fossil’. Hugh MacDiarmid retorted: “Mr Trocchi seems to imagine that the burning questions in the world today are lesbianism, homosexuality and matters of that kind. I don’t think so at all. I am a Communist, and a Scottish Nationalist and I ask Trocchi and others, where in any of the literature they are referring to … are the crucial burning questions of the day being dealt with, as they have been dealt with in Scottish literature, if you know enough about it” to which Trocchi responds, “We have been exerting our nationalism in Scotland as long as I can remember, and I am damned sick of it.”

All of which may sound strangely familiar.

Here is precisely the contemporary debate played out.

The false dichotomy between ‘identity politics’ and essential ideas of Communism and Nationalism, class and state being fought out and over in 1962 and in 2025, some 63 years later. MacDiarmid and Trocchi foreshadow our contemporary ‘debates’ but they have something to tell us about them. Both bring something to the party, both are blinded (almost – a ‘certain love and respect’) to the others world.

I think the reasons these ideas play out over and over is that they represent something essential and problematic about the human condition and our politics and culture, and we can add some distinctively Scottish elements to it all (Calvin Klaxon!).

But what if the perceived schism between Trocchi and MacDiarmid, between the Old Guard (‘fossil’) and Usurper was a false one? What if the perceived schism between National and International was a false one? What if the idea of a binary choice between ‘identity politics’ (the term obviously wasn’t coined in 1962) and ‘socialism’ or ‘material conditions’ was a false one? What is the essentialism between personal and public, between ‘lesbianism, homosexuality and matters of that kind’ and ‘bread and butter issues’ was a misdirection?

It is easy to side with – and relate to – Trocchi’s take down of the ‘turgid, petty, provincial, the stale porridge’ – god I am sick of it more than a half century [and you’re bloody part of it – Ed]. But equally MacDiarmid’s disdain and dismissal is a desultory one.

The reality is we don’t have to choose.

The dichotomy is false.

Our past and our future is both MacDiarmid’s and Trocchi’s – both aspects of a debate and a culture that needs radically updated and transcended. The only way that these issue are ‘resolved’ and properly understood is through actual, meaningful self-determination, the goal of both writers, through a process that meaningfully changes material conditions of Scotland’s grotesque social inequality and is liberatory for all of our people. All of this is possible.

Generational change, challenging orthodoxies and shibboleths, is an endless essential process as natural as children leaving home or us ascending consciousness. Healing (too banal – that’s the current ‘theme’ of the Edinburgh Book Festival) or transcending the binary is a dialectical process (oops picked a side there – catch yourself) is essential. This is not a call for a false unity, it is however a call for a cross-dressing, an understanding that we are actually (really) ‘all in this together’ and the times are so dark that the urge to just embed oneself within one camp or another isn’t adequate any more, even if that allows some comfort. As we’re understanding ‘we’re all on a spectrum’ and that’s okay, that’s actually a great way to orientate in disorienting times. This doesn’t mean that nothing is fixed, or you don’t have core beliefs, identity, belonging or being, it just means that that’s relational, and that’s okay. It’s not a threat, It’s okay. All can be.

What is striking about the Sigma Portfolio is how ridiculous it seems to our eyes. Such stupid hope, such stupid reach, such grandeur, such wild optimism. Jesus, could we do with that now? The mirror of the idea of a cultural event (such as 1962) in Scotland being of any significance at all to anyone is unfathomable. We are left with such stale porridge Trocchi couldn’t even conceive of.

The legacy of the various revolutions and counter-cultures of the 1960s are more than disputed. They are bastardised, commodified and distorted. Large sections of the obscene far-right lay claim to and draw on the libertarionism of the period. This is not theirs to claim. Just as we reclaim Trocchi we must challenge the obscenity of the right owning and distorting the radical elements of the counter-culture and renew it again. Our lives depend on it.

What an interesting, thought-provoking, and energising piece. And so good to challenge the false opposition between identity politics on the one hand and the politics of class or nation on the other.

Good stuff. After the big bust-up MacDiarmid and Trocchi went on to be mutual admirers and often wrote back and forth.

Trocchi emerged as a deliberately philosophical kind of post-war artist via Glasgow University, with a rather mangled programme of freedom and transgression partly taken from Sartre and partly from Nietzsche (White was the same ).

He looks backwards to de Sade in some ways and stylistically to the Nietzsche of Thus Spake Zarathustra (so, in ‘Cain’s book’ genres are disavowed and he moves between story, phenomenological description, and philosophical statement).

But everyone knows he always traded on his overblown artistic reputation ruthlessly and ended up a non-writing middle aged junkie hustler, dealing NHS heroin on the side, living not a far cry from Kensington but actually IN Kensington (current average house price £2,395,000).

Hi Innes, thanks, yeah Trocchi’s political legacy is debateable, aside from his influence on literature and Scottish magazine culture. It’s quite a complex disputed terrain imho about what that generation left us …

Politically, I don’t think he was entirely wrong, and I suspect that’s where he and MacDiarmid were in sympathy if not necessarily in agreement.

Scottish piety always asserted its revolutionary status, “fighting” capitalism etc (right up until it became today’s municipal devolutionism). The only consistent and interesting legacy of the era is existentialism, which turns up everywhere, from John Macquarrie to Spark to Kelman, etc.

This is so important to know even though out of time in my own case. How deprived of real knowledge was my own greatest education system in the world. I knew nothing of these radical artists until my old age. What a heritage of complexity it is to be from Scotland. If only there were more of those courageous writers and artists today willing to continue the radical democratic tradition.

Arguably the rave/club scene which exploded in Glasgow and elsewhere at the of the 80s was the closest thing we’re likely to get to Trocchi’s meeting of a million minds… But it kind of defies analysis…

Britain still feels incredibly stuffy, and that is unsurprising as it’s the same private school / Oxbridge set who run the country, and still show their prudery and narrow conservatism from time to time…

Jeremy Thomas, probably the best UK film producer of the last 50 years, was famously locked out the allocation of the mega lottery funded film consortiums back in 2000 because he had produced David Cronenburg’s “Crash” based on the JG Ballard novel, too risque by far to be encouraged… (Andrew MacDonald’s DNA was one of the recipients)…

As for the 60s in general, so many of that generation went on to lead the neo-liberal revolution of the 80s and probably very few people these days in Scotland know who Trocchi or MacDiarmid (whose cottage near Moffat is in disrepair) even are…

To talk of even the possibility of a revolution is seen as eccentricity at best, if not madness, and the whole intellectual project of human liberation of the last two thousands years has virtually been parked to one side…

As for identity politics, it is everywhere, and while clearly necessary to protect some minorities, it also serves to perpetuate the neoliberal status quo… It’s an American import which sees us all cast as victims of some kind of discrimination/ handicap. or another, and feeds into the culture of narcissim of our times…

You’re that it’s not either / or though…

Good piece, Mike…

Was not it always ‘eccentric’ to believe in such a revolution? It was not even clear what the revolution really might consist of. Arguably people like Trocchi were simply deluded. Still, I agree with Mike – we could do with some of that wishful, dynamic, wild thinking now. But it should come from the ground up, not the top and those doing it need bravery.

You say the UK feels ‘stuffy’ but to me it is not so much stuffy as conservative in the sense that the mainstream has more power than ever to dictate what creative people can do. This is linked to neo-liberalism rather than stuffiness. If you look at some of the creative work that might appear on the BBC in the 1970s, it was often more interesting and experimental than now. It is commercial pressures that have caused this, bums on seats and all of that.

I would argue that the ‘stuffiness’ that does feed into this ‘safe’, commerical mindset, is actually most present in the so-called ‘progressive’ mindset – imagine Trocchi and The Beats appearing today with their crazy, wild and offensive ideas? They’d be mincemeat in the current zeitgeist, not because some of it would not go down well, but because some would not and that is all it would take to outlaw such an artist today. This is having a stultifying effect on creative thinking – artists are looking over their shoulder not so much at the powers that be, but at their peers and into their own minds. Ironically it is official funders that have also absorbed and then sanctioned this progressive ideal.

As for history and remembering, I dunno, did Trocchi give a damn about the past and looking at official remembrance of it? Did he learn about such stuff at school? Does not ‘institutions’ remembering such radical thinkers, sanitise and commodify them anyway? I think it should come more from the grass roots, radical artists today breaking the bounds, rather than looking to the establishment to package past anti-establishment movements and people.

Hi Niemand,

No, I really don’t think it was eccentric to believe in the revolution in the past, though it’s not a straight line, there were, over the course of two centuries,, revolutionary moments and then deeply counter-revolutionary moments, but certainly the 60s and early 70s were moments when young people felt change was coming.

You see that in the New Waves in film, directors like Godard or Fassbinder, and in the peak year of 1968, the Cannes film festival was interrupted and suspended in solidarity with the workers and students of May 68…something which could never happen today…

Of course, it was always a minority, but it was an articulate and influential minority…

The 1930s even more so, with capitalism.in deep crisis and the Soviet Union having industrialised in record time, a whole generation of British intellectuals became Communists because they thought capitalism was on the way out, which partly explains why so many went to Spain… MacDiarmid was fairly typical in becoming a Communist…

Britain has always been an anti-intellectual country, a country where the arts have but marginal interest, and as a protestant country, the national sport is hypocrisy (Catholics get to be bad and repent) and it is a bit of an outlier to the rest of Europe. This most singular thing is that every country has had a revolution in the modern period, except Britain, some countries like France have had several… We haven’t had one since 1689!!! So the same elite families or networks are often still in place…

So we have this stuffy, class obsessed, deeply conservative, at times frankly comical ruling class who bond through very expensive private schooling or else through bloodines like horse-breeding…

And the key philosophers are Burke and John Stuart Miller and Karl Popper, all anti-revolutionary philosophers first and foremost, whereas the French or the Italians gave us Rousseau and Voltaire and Gramsci, who are the opposite… Orwell.is so popular in the UK because he fits so snugly into the anti-revolutionary tradition…

It’s a country where someone like Jeremy Paxman or Jeremy Clarkson are perceived as being outre…

It’s the class system which lies at the heart of the whole cultural tenor of Britain… The Scots have a bit of it, but not nearly as bad…

Apropos of nothing in particular. I was in the queue of a small bakery and cafe on Great Western Road when two students just ahead of me in the queue began talking about Alexander Trocchi. One said that she had heard he was from Glasgow and the other said, ‘Is that so?”. I interjected politely and pointed out of the window and said, “That is Bank St. He was born there.”

They ordered their takeaway coffees, paid and left.

Great story!

The schism between MacDiarmid and Trocchi is a continuation of the same argument put forward by Edwin Muir for the use of ‘Lallands’ in Scottish Literature- Muir believed that MacDiarmid’s curated standardised hot-house version of Scots was too restrictive and reductionist as an expressive framework for Scottish Literature- Muir for example argued how can we communicate sophisticated complex ideas in such a reductively simplistic syntax as MacDiarmid’s Lallands? If poetry is already a niche highly refined form of syntax that alienates the casual reader- then why add another layer of alienation in the form of a made-up literary Scots? Our other great poets of the 20th century, MacCaig and George Mackay Brown were of the same mind as Muir on the subject. Scots is too varied and geographically diverse to be standardised. There are great similarities between Dorich and Lowland Scots but also great differences and the differences are such that if you removed them that neither would retain their unique local identity.

Such is MacDiarmid’s power and influence over Scottish literary culture that some simplified form of his ‘Lallands’ has become the standard syntax in mainstream Scottish literary circles, and has been the main artistic form of expression for such writers as Liz Lochhead, Tom Leonard, Jackie Kay, Irvine Welsh and Kelman. Although I would argue Kelman’s and Leonards use of Scots is much more sophisticated and complex than the standard tunnocks tea-cake version of someone like Kay. It’s this tunnock tea cake version of Scots that is championed by much of the Scottish literary elite and if used strategically can open up opportunities for writers looking to beguile the cultural gatekeepers- such is its ubiquity I sometimes wonder if the likes of Edwin Morgan, Kenneth White or Iain Crichton Smith would be published today in Scotland. Going against the mainstream to gain poetic recognition for the likes of Roddy Lumsden, Robin Robertson, Don Paterson or John Burnside has meant either leaving Scotland or having links to elite universities such as St Andrews, Oxford or Cambridge, winning the Forward and TS Eliot prize, or a combination of these elements in order to gain recognition in their homeland- particularly if you don’t acquiesce to the specific diktats of the Scottish literary gatekeepers cultural cudgel.

I am keen to learn more about the ‘great differences’ between Dorich and Scots. I have never encountered ‘Dorich’. Where is it spoken, and who has suggested removing the differences between them?

‘Lallands’ is also new to me, as is the Tunnock’s tea cake version of Scots. Scotland is clearly a more linguistically diverse country than I had ever suspected.

LOLs

The confusion comes from me using the word ‘Lallands’ instead of Lallans’. ‘Lallans’ a Modern Scots variant of the word lawlands or Lallands, (referring to the lowlands of Scotland), is a term that was traditionally used to refer to the SCOTS language as a WHOLE.

HOWEVER, more recent interpretations assume it refers to the dialects of SOUTH and CENTRAL Scotland, while DORIC, a term once used to refer to Scots dialects in general, is now generally seen to refer to the MID-NORTHERN Scots dialects spoken in the NORTH-EASTof Scotland, for example Aberdeenshire.

The term Lallans was also used during the Scottish Renaissance of the early 20th century to refer to what Hugh MacDiarmid called synthetic Scots, i.e., a synthesis integrating, blending, and combining various forms of the Scots language, both vernacular and archaic- MacDiarmid consciously designed this type of Scots for the intention of creating a new ‘standardised’ synthetic Scottish literature.

This synthetic Lallans resulted in Scots words grafted on to a standard English grammatical structure by and large removed from traditional spoken Scots- many of these literary practitioners did not speak authentic Lowland Scots, and I include the likes of Sidney Goodsir Smith or Violet jacob- I would include the likes of Jackie Kay in that. The likes of Kay creates a ‘tunnocks tea-cake’ version of Scots, as do many others ‘luminaries’ in Scottish literary world. Using twee words hardly anyone uses and often out of context. This additional ‘modern’ version of Scots utilised by the likes of Kay or Lochhead is a seen the conscious creation of a ‘mainstream’ variety of Scots — a standard literary variety,…I would maybe refer to it as ‘synthetic Scots’, now generally goes under the name Lallans (=Lowlands or Lallands)…. In its grammar and spelling, it shows the marked influence of Standard English, more so than other Scots dialects.

And yes ‘Scotland is clearly a more linguistically diverse country than I had ever suspected’…there are clear differences between much of the Scots used in the West of Scotland and Greater Glasgow compared to the likes of Hawick and surrounding border residents are known to possess a dialect and accent slightly different from broader Scots, being classed as Southern Scots or Borders Scots- there are of course differences between the Doric Scots spoken in Aberdeenshire and the Scots in Shetland or Orkney…to remove the key differences between these dialects of Scots would be to destroy the local character and linguistic uniqueness of each variant.