Situating Cain’s Book

This is adapted from a talk at the Trocchi at 100 event in the Kelvinhall Glasgow organised by the Department of Scottish Literature at Glasgow University and the Andrew Hook Centre for American Studies.

There is always the writerly temptation to mimic the style of the author you are writing about, one that is always at risk of descending into cheap parody. It’s a temptation I find hard to resist in these circumstances. Why have I, a humble writer and bookseller, found myself here, delivering a talk about the work of Alexander Trocchi at a university, an institution he actively abhorred? I cannot help but feel like Red Peter, the ape from the Kafka story, desperately trying to gain the respect of my peers with this Report to the Academy. Yet here I am, speaking with the same inarticulable compulsion as the narrator of Cain’s Book, Joe Necchi, about its putative author, Alexander Trocchi.

Ever since encountering his work as an undergraduate almost twenty years ago, I’ve been obsessed with Alexander Trocchi’s commitment to both avant-garde poetics and politics and how they might be related. In particular I have always wanted to explore if there was any throughline between the aesthetic inheritance from Samuel Beckett to the anti-ideology of his Sigma Portfolio. After being accepted to deliver this talk I did not need to deliver I have found myself, like Joe Necchi, ‘from day to day accumulating, blindly following this or that train of thought, each in itself possessed of no more implication than a flower or a spring breeze or a molehill or a falling star or the cackle of geese.’

‘The best would be not to begin. But I have to begin,’ as Beckett’s unnamable narrator has it. Alexander Trocchi’s instrumental role in establishing Samuel Beckett’s literary stature in the English-speaking world is well acknowledged, publishing the first English translations of his post-war French novels in Merlin magazine which he edited during his time in Paris in the early 1950s. It is easy to see why the two writers struck such a bond with the manifest parallels between their lives and works. Both felt compelled to leave their homelands to pursue their artistic callings and were seriously committed to building on the modernist tradition of pushing the boundaries of literary form. In strident editorials, Trocchi firmly pinned his colours to the modernist mast and made his aesthetic positions clear. In the volume two, for example, his editorial declaimed that ‘most of the traditional categories are merely distinctions hallowed by antiquity, which have been allowed to harden, and which, in the hands of unscience, have become an inquisitorial rack to which the mesh of contemporary writing is to be twisted.’ The hands of unscience would certainly struggle to shackle the aporetic monologues of Beckett’s Trilogy to such a rack.

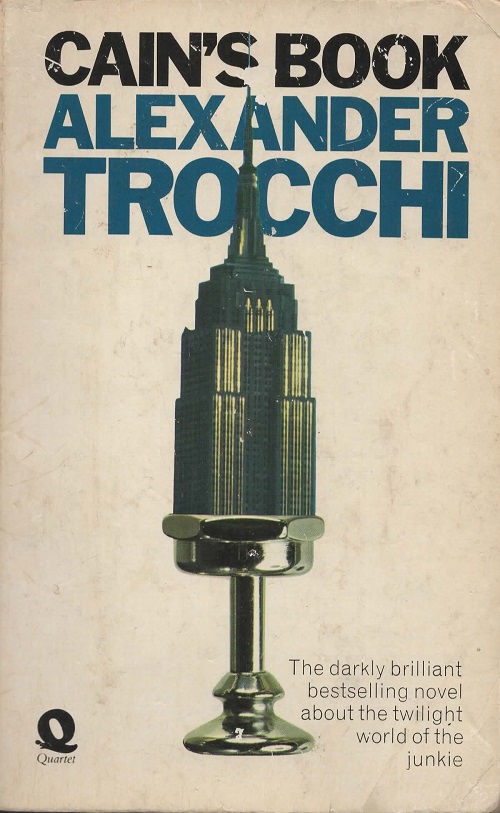

Trocchi would barely have encountered Beckett’s work while he was finishing his first novel Young Adam but the marks of the Irish writer’s influence on Cain’s Book are undeniable and even explicit: a whole paragraph of Malone Dies appears as an epigraph to a latter section of the novel. In the Trilogy, Samuel Beckett demolished the epistemological foundations of foregoing capital ‘L’ literature, and it was in this rubble that Trocchi scrabbled to narrate the tenebrous realm of the junkie in late 1950s New York. While in the Trilogy, the external world is eventually pared down to one articulating consciousness that has doubted itself into an existence that is unsure if it even exists, Trocchi grafts these quivering truths on to the life of the heroin user. The compulsion to write against unmeaning is folded into the ineluctable cycle of addiction where the past and future have dissolved into an endless present which defies narrative shape, structured centripetally around one New Year’s eve. There is no story to tell opens one section of Cain’s Book much like the anguished narrator of The Unnamable who at one point announces ‘no more stories from this day forth, and the stories go on.’ And even as they try to tell these stories, they cannot be sure if they are the ones narrating them. ‘Identities, like the successive skins of onions, are shed, each as soon as it is contemplated; caught in the act of pretending to be conscious, they are seen, the confidence men,’ thinks Necchi just as in The Unnamable the narrator reflects ‘All these Murphys, Molloys and Malones do not fool me. They have made me waste my time, suffer for nothing, speak of them when, in order to stop speaking, I should have spoken of me and of me alone.’ Not even the very words can be trusted. Remarking on a conversation, Joe Necchi says ‘the inauthenticity was in the words, clinging to them like barnacles to a ship’s hull, a growing impediment.’ This idea of words as a barrier to truth is a persistent anguish of The Unnamable’s narrator too: ‘Words, he says he knows they are words. But how can he know, who has never heard anything else.’ This all proceeds from Beckett’s vexed relationship with language, explaining in a letter in 1937 that language for him is ‘like a veil that must be torn in order to get at the things (or the Nothingness) behind it.’

After the publication of Cain’s Book, Trocchi did not publish any more novel-length works of fiction. Perhaps this should be of no surprise given that at one point Joe Necchi tells a woman in another scow that:

the great urgency for literature was that it should for once and for all accomplish its dying, that it wasn’t that writing shouldn’t be written, but that a man should annihilate prescriptions of all past form in his own soul, refuse to consider what he wrote in terms of literature, judge it solely in terms of his living.

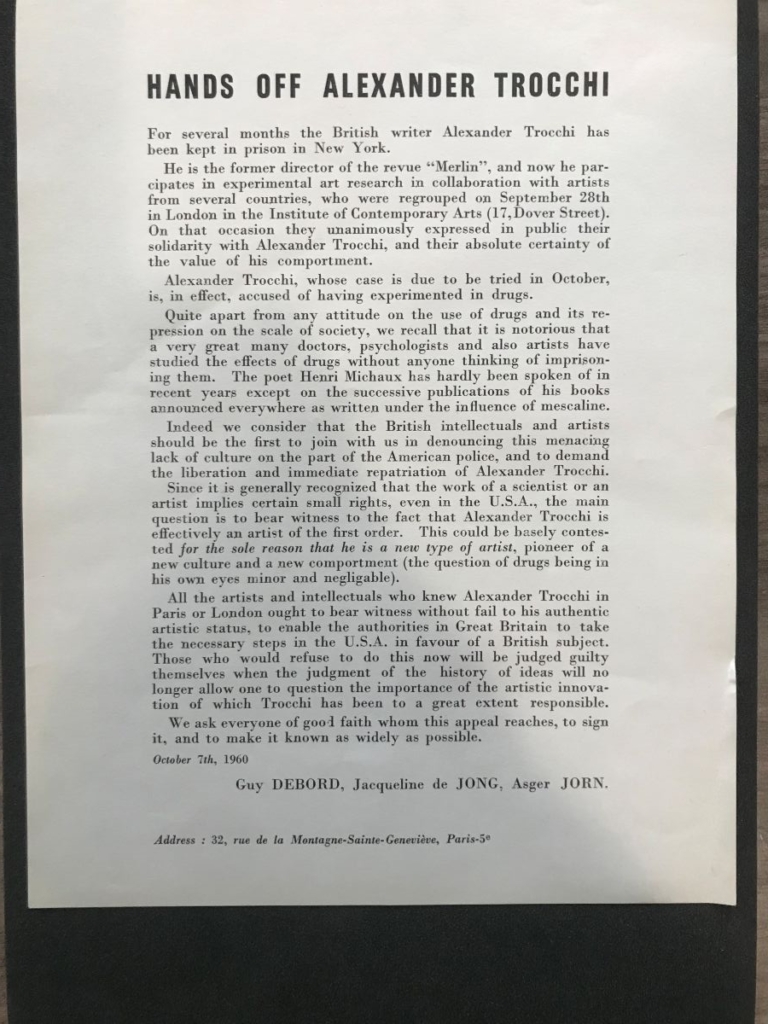

It was from henceforth that Trocchi sought to channel his writing energies into transforming the art of living, announcing this with his essay ‘The Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds.’ Reflecting on his legacy the year after his death, John Calder wrote ‘what Sigma was really about was unclear to all except a few devotees, but it gave Trocchi an excuse to avoid getting on with a sequel to Cain’s Book.’ To me I feel it incumbent to read his political writings as the afterlife of a literature which he believed was dead, moulded as much by the modernist sensibility of Cain’s Book as his shortlived membership of the Situationist International (before getting kicked out by Guy Debord like everyone else). Indeed in ‘Sigma: A Tactical Blueprint’, the other major essay outlining his political project, Trocchi explains that all previous forms must be dismissed as ‘that is what we mean when we say that “literature is dead”; not that some people won’t write (indeed, perhaps all people will), or even write a novel (although we feel this category has about outlived its usefulness), but the writing of anything in terms of capitalist economy, as an economic act, with reference to economic limits, it is not, in our view, interesting. It is business.’ Literature is just one of what he calls ‘yesterday’s abstractions’, upholding the degrading society of the spectacle.

Whereas Samuel Beckett’s fiction could not imagine any escape from the barren and constricted environs of the human skull, Alexander Trocchi diverged from his literary mentor in believing that transcendence from solipsism was possible. This goes against the claim of T. J. Clark, a fellow British situationist, who wrote in the 1999 book, Farewell to an Idea ‘modernism turns on the impossibility of transcendence.’ The hopelessly involuted self-consciousness of Cain’s Book is refashioned as a potential panacea in his quest to unleash homo ludens in ‘Sigma: A Tactical Blueprint’:

It is our contention that, for many years now, a change, which might be usefully regarded as evolutionary, has been taking place in the minds of men; they have been becoming aware of the implications of self-consciousness. And, here and there throughout the world, individuals are more or less purposively concerned with evolving techniques to inspire and sustain self-consciousness in all men.

All the ontological instabilities that fissure Cain’s Book are conveniently forgotten.

Both ‘The Invisible Insurrection of a Million Minds’ and ‘Sigma: A Tactical Blueprint’ are written with a millenarian zeal that is typical of the revolutionary ferment of its time, composed of a potpourri of ideological strains: situationism, anarcho-libertarianism, Trotskyist vanguardism and proto-accelerationism. To closely scrutinise the texts exposes many latent contradictions that would not survive contact with the reality of political organising. Moreover, they are already present in the fictions of Beckett to which he owed such a philosophical debt. In one of his theorisations of the sigma project, Trocchi writes ‘Now and in the future our centre is everywhere, our circumference nowhere. No-one is in control,’ anticipating the diffuse model of grassroots power that can circumvent institutions, like the multitude of the autonomous Marxist tradition. In his study, Samuel Beckett: Repetition, Theory and Text, Steven Connor identifies this same persistent image in Beckett’s fictions:

The image which is used often in the Trilogy, as it is in Watt, to explore the relationship of ontological supremacy and subordination is that of a circle, with its centre and circumference. The voice in The Unnamable imagines itself as occupying the centre of its vault, with other characters wheeling round it like heavenly bodies round the fixed earth of the medieval cosmos. But though the voice concludes that ‘the best is to think of myself as fixed and at the centre of this place’, it also concedes that ‘nothing is less certain than this fact,’ recognizing that being circled by Malone need not imply its own fixity, but could indicate that both are in motion. The image of the centre of the circle is a suggestive one. A centre forms part of the circle that it occupies even as it represents its inner, originating principle. But, as the latter, the centre is also, in a sense, outside the circle, as the still point where as is at rest, with no extension in either of the circle’s two dimensions…The voice in the The Unnamable is not able to conceive itself securely either as centre or circumference.

Not only does this image of the circle underscore the lack of fixity of the subject, Trocchi goes on to further contradict his diffuse revolutionary consciousness by proposing that his ‘spontaneous university’ ‘should not be farther from London than Oxford or Cambridge, for we must be located within striking distance of the metropolis, since many of our undertakings will be in relation to cultural phenomena already established there…If we were to locate ourselves too far away from the centers of power, we should run the risk of being regarded by some of those we are concerned to attract as a group of utopian escapists, spiritual exiles, hellbent for Shangri-La on the bicycle of our frustration.’ Setting aside the fear of being cast as unmoored idealists, the propulsive recursion of ‘I can’t go on, I’ll go on’ is transmogrified into ‘we don’t need an institution, we need an institution’ as he tries to square an anarchist ethos with an acknowledgement of the need for some institutional form.

Holding these contradictory positions in dialectical tension speaks to the continued failures of left organising to this day and I cannot help but wonder if this rhetorical instability at the core of Trocchi’s polemics feeds into our current revolutionary failures. As McKenzie Wark observed in his study of the situationists, ‘the spectacle required a structural transformation which no mere passing of informations between disaffected hipsters could ever achieve.’ I don’t believe it is a coincidence that after the fall of the USSR and the increased disillusion of party politics that there was an upsurge of interest in his political writings, even inspiring an exhibition in Bilbao in 2005. This culminated in what the subtitle of Vincent Bevins’ book, If We Burn, describes as ‘the mass protest decade and the missing revolution.’ In his conclusion, Bevins’ diagnoses the flaws in the fetishisation of leaderless movements in left organising during the 2010s arguing, ‘organization works, and you can use it for good or for evil. It was an overreaction to reject them simply because they led to trauma in the twentieth century, and it is a mistake when “the establishment of structures of any kind is sensed as the start of a slippery slope towards the gulag.”

The bleak terminus to this train of thought is that we are condemned to only arrive in the universe of Beckett’s work: atomised heads in urns born astride the grave in an irradiated landscape waiting for an end that never comes. But perhaps it is only in immersing ourselves in this ending forever postponed that new beginnings can be salvaged. This is the contention of the philosopher Ben Ware’s 2024 book, On Extinction which attempts to think through political and social transformation by concentrating on forms of the end. Appealing to the work of Simone Weil, he posits the idea of revolutionary decreation who wrote that ‘we participate in the creation of the world by decreating ourselves.’ It is hard not to imagine that Trocchi would have found an affinity in Weil’s claim that it is necessary to dissolve the self into nothingness, ‘in order to liberate a tied-up energy, in order to possess an energy which is free and capable of understanding the true relationships of things.’ Ware goes on to ask:

How then to bring about ‘the total redemption of humanity’ (to use Marx’s own deliberately theological phrase)? The answer, simply put, is revolutionary decreation. As Lukács neatly summarizes in his History and Class Consciousness (1922): ‘The proletariat only perfects itself by annihilating and transcending its self, by creating the classless society through the successful conclusion of its own class struggle.’

Once again, Gyorgy Lukacs rides to the rescue of a modernist writer whose aesthetics he would only have poured scorn over. No doubt Trocchi himself would have found the dogmatic Stalinist an unlikely defender of his dialectic of annihilation and transcendence.

As I construct this document on the 9.15 train from Edinburgh to Glasgow and currently read out these words that I can barely remember writing, like Joe Necchi at the end of Cain’s Book, I feel I am only beginning to say what I mean. I am also an agent of what is unremembered, rejected. I pore through my notes and see all the directions of thoughts not followed, all of my re-reading of Adorno and the situationists for nothing. Instead I must content myself with this tentative organisation of ambiguous data, this hastily woven fabric of detournement. I can only resort to the cheap device of literary ventriloquism and affirm my ending with words that are not my own ‘knowing again that nothing is ending, and certainly not this.’

Was Merlin magazine yet another publication funded by the CIA?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Merlin_(literary_magazine)

As Frances Stonor Saunders recounts in Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War, these European postwar literary rags were such unpopular shite that the US State Department and CIA fronts had to keep them afloat not only with secret funding but by buying 10,000s of copies themselves. Which explains a lot. And like ‘modern art’, no threat at all to business as usual. As revolutionary as a turnstile. Are there landfills somewhere?

I notice the suggestion that the suggestion ‘Trocchi claimed that the journal came to an end when the United States Department of State canceled its many subscriptions in protest over an article by Jean-Paul Sartre’ is unreferenced (and spelled wrong). It begs so many questions that are unanswered. There may be proper research on Merlin and its funding somewhere of course.

I have always thought there is a certain amount artistic hubris from artists on art changing the world, especially in a political sense but having read The Unnameable I would say modern art certainly has the capacity to shift consciousness quite profoundly. It is a tough read, but I have never forgotten it, its seeming endless contradictions and circular narrations, a profound reflection of human consciousness. And the point is that reflection back to the reader is enlightening and makes one think of the world a little differently and on the whole, despite the bleakness of the ‘novel’, to the good.

@Niemand, don’t you think that Art which retreats from Nature, which emphasises individual human consciousness (and basically allows the appreciator to endlessly project themselves upon it), is perhaps the source of many of the evils we face today? Or at least a diversion from the things that should have been occupying our minds, like Earth systems, nonhuman life and geopolitics? At least, that may have been the reason the CIA funded it.

And we also have national security cinema and the likes, projecting an alternative gang-ho militarism, another form of deadly narcissism funded by the same shadowy bodies. Why would we accept NATO’s warmongering and nuclear weapons else?

Do the ideas that Art communicates have to be difficult, ambiguous and obscure? Or is that a sign we are being gaslit?

My recent reading has touched on themes related to the propaganda value of the (artistic or otherwise but almost always ‘Western’) ‘genius’ which has supported a hierarchy of humanity, which is related to the professionalisation and cult of the artist, racial pseudoscience and eugenics, and of the Great Man (Occasionally Woman) View of History. And cutthroat Battle Royale competition in some schools.

When we see public art, history and science funded openly by the likes of fossil fuel companies, is that simply reputation-washing, or is such Art a useful distortion mechanism through which we public are supposed to accept the otherwise unacceptable? Maybe Artsworld becomes something of a prison, albeit sometimes a gilded cage, for Artists? Who become essentially managers of their own reputations.

Where is the art form which teaches us how to collectively organise for a better world?

There is a danger that appeals to the ‘natural’ in the arts is very much a conservative approach: good art is that which does not go against ‘nature’, meaning anything abstract, nonrepresentational, atonal, not narrative based etc is ‘unnatural’ whether it is in art, music, literature, whatever. I find this mostly associated with reactionaries. It is hard to imagine art that does not come from individual human consciousness.

I suppose some art is trying to teach us something and there is nothing wrong with that, but that takes a very utilitarian approach to it. Most artists do not do art to teach something to the receiver of it, it is far too didactic, anti-art really. It is art’s ambiguity that gives it its real life and actually gets through to people. It is why I talked about shifting consciousness – this can have positive knock-on effects. The artist may or may not be highly conscious of trying to do this, though on some level I think they always are, since it stems from the approach they have to their materials.

If you are looking to art to teach about organising a better world, then you will remain disappointed in it. In specific political terms like that, it does not just become moribund, it will most likely fail.

@Niemand, I find it strange that you associate Nature with reactionaries, given the obvious discrepancy with modern ecological movements and their opponents. In fact you contradict yourself, because if Art isn’t about improving the world, what is it but reactionary (at best)?

What do you make of the documentary Ocean with David Attenborough (2025), in light of our discussion?

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt33022710/

It is the phrase ‘arts retreats from Nature’ that rings those alarms. What do you mean by Nature? You see in my sphere – music, attacks on dissonant / atonal music nearly always stem from this sort of idea. It is supposedly based on the idea that the natural harmonic series (a scientifically fixed phenomenon) should form the basis of compositional organisation which leads to the use of conventional tonal harmony (which does derive and stick closely to the patterns of the harmonic series). Going against that and say, organising your musical materials using whatever method you choose, is not just bad, but unnatural, decadent and indulgent.

As for literally meaning the natural world of non-human plants and animals, art is a mirror so has reflected, say, the urban world for as long as it has existed and will continue to do so. I think the main point is art really is that mirror. It has no agency of itself.

Oh and yes, I like the Ocean series but I do not view it as art as such. It uses various artistic practices to get a point across, some of which, like the music, I think are actually quite bad (hackneyed and formulaic), but no matter because that is not the point of it. And thus the point of it also is very much not art.

@Niemand (Ocean is a new one-off departure, not a series), well perhaps then *this* is art?

Our Story With David Attenborough and The Herds: a new theatre of the Anthropocene

“A cinematic immersive experience and stampeding animal puppets are bringing the climate emergency into the city”

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/jun/20/the-guardian-view-on-our-story-with-david-attenborough-and-the-herds-a-new-theatre-of-the-anthropocene

I think documentary-making is an art form. I’ve also read the related book Ocean: Earth’s Last Wilderness which features graphic art, photography, text.

I’ve also just read Guy Delisle’s graphic novel on Eadward Muybridge which captures some of the forward-thinking required for artists to accurately capture the natural world (here the movement of animals). While they may have been reactionary elements in Artsworld, there was clearly a motive to move forward with depictions. I also recently read about the pioneering work of Maria Sibylla Merian in botanical and insect painting in the remote field, again the opposite of reactionary. Music may be an exception; I’m aware that animators for instance draw heavily on natural sources.

Your position appears to me like the Modern Doctor Who fans who celebrate its move since reboot towards fantasy, feelings and flattery. I mean, that’s Art too, but the retreat from Nature rings alarm bells for me, and puts the Humans-First show at odds with some powerful science fiction and fantasy shows from the USA which engage critically with more globally-relevant topical issues.

I was influenced years ago by EH Gombrich’s Art and Illusion, which explains how many aspects of art had to be invented, refined, understood in terms of human psychology and acculturation (perspective and map-reading were two examples, if I recall). So I reject the idea that art is a mirror. For much of human history, human artists have been unable or unwilling to accurately replicate the Nature before them. This is of course due to perception being a psychological as well as an organic sensory process. And much of art depends on exploiting our organic nature (which must apply to music too, even if we nicked it from birdsong).

When I mentioned fossil fuel sponsorship, I might have been thinking of this UK Government and Parliament petition (with map):

https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/700024

which got the required 100,000+ signatures to be debated by UK Parliament on on 7 July 2025 (apparently). What arguments will be put forward for defending business-as-usual, I wonder?

But what about sponsorship by the CIA and the like? Will that still be legal?

What is spelled wrong?

‘canceled’

Actually I just realised that canceled with on L is used in the US which is a bit ironic as I used ‘spelled’ is also more US than spelt. I suspect this was what you were indicating, ha ha.

It does tell us the entry may well have written by an American