The Multi-Species Paradigm in Traditional (Gaelic) Folklore

This is from Professor Mairéad Nic Craith research published in the open access book ‘Narrating the Multispecies World’, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

In her masterful novel, The Island of the Missing Trees, Elif Shafak (2022) tells the story of two young lovers in a divided postcolonial 1974 Cyprus. One is Christian and Greek and the other is Turkish and Muslim. What is remarkable about Shafak’s novel is the role played by a fig tree that grows in the middle of a cafe. The tree is the third character and plays a central role in the narrative. As well as witnessing the huge range of emotions involved in a forbidden human love story, the tree narrates the story from the perspective of other animals, plants and insects. Early in the novel, the tree laments the lack of interest from humans in other-than-human species. After observing them for a long them, the tree arrives at the conclusion that humans “do not really want to know about plants” (Shafak 2022: 44). They do not wish to know whether plants are capable of kinship and emotions. “They find it easier, I guess, to assume that trees having no brain in the conventional sense, can only experience the most rudimentary experience” (Shafak 2022: 44). The rest of the novel is a powerful exploration of love and fear from the perspective of different species.

My contribution focuses on the multi-species relationships that is evident in traditional Gaelic folk narratives. Building on a previous blog in Bella Caledonia, this contribution explores the extent to which such folktales engage with an other-than-human world and examines the role of multispecies temporalities in these narratives. Drawing on the Gaelic ontological concept of dùthchas/dúchas [heritage], and on examples of folklore from the Gaelic culture, my key argument is that traditional folk narratives can teach us lessons about interactions between humans and other species. The paper investigates the extent to which folk-narratives preserve memories of historical ecologies and asks whether these can be revived, re-envisaged or re-purposed to develop new possibilities for cohabitation in the multi-species world. My focus on Gaelic folktales derives from the fact that I grew up in Ireland and now live in Scotland – but I recognise that many of the points I make concerning Gaelic folk narratives also apply to other Indigenous cosmologies.

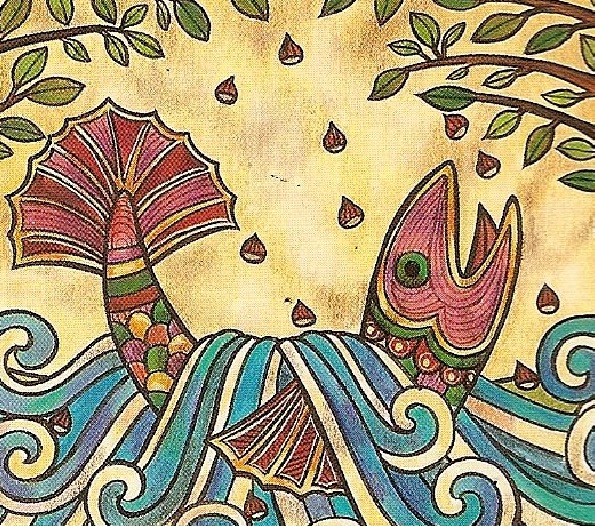

Salmon of Knowledge.

Patchy Anthropocene

In recent centuries, humans have increasingly distanced themselves from other species, but this has not always been the case. The Anthropocene is the term commonly used to profile the contemporary hierarchical relationship that humans have with the rest of the species on the planet. There are power implications inherent in the concept which imply that mankind is the single most influential species and has effectively influenced, and tamed nature to such an extent that he has fundamentally altered biological systems. Human impact on nature has not been a positive phenomenon. It has led to climate change, the nuclear bomb and the rise of toxic activity on earth. As they destroy the planet, humans are increasingly alienated from their environment.

This hierarchical paradigm is powerfully captured by Irish eco-philosopher John Moriarty in a story from his childhood. Living on a rural farm in the west of Ireland, he describes one Christmas eve. The excitement was palpable. The candles were lighting, the cake was ready and Santa was on the way with a game of snakes and ladders:

“There was no denying it, it was wonderful, and in a glow of fellow feeling with all our animals I went out and crossed the yard to the cowstall. Pushing open the door, I looked in and at first I just couldn’t believe what I was seeing, no candles lighting in the windows, no holly, no crib, no expectation of kings or of angels, no sense of miracles. What I saw was what I would see on any other night, eleven shorthorn cows, some of them standing, some of them lying down, some of them eating hay, and some of them chewing the cud, and two of them turning to look at me. Devastated, I had to admit it was an ordinary night in the stall. Coming back across the yard I looked at the fowl house and the piggery and the darkness, and the silence that had settled on them couldn’t say it more clearly. Christmas didn’t happen in the outhouses. Christmas didn’t happen to the animals. The animals were left out. And since the animals were left out, so, inside me somewhere, was I. In our house everything turned out as we expected it would […] but I couldn’t forget the dark stall.” (Moriarty 2011: 6)

This personal narrative clearly reflects the hierarchical relations implicit in the Anthropocene model. But the Anthropocene concept is increasingly regarded as contentious and has been modified by social anthropologist Anna Tsing and others to counteract its implied homogeneity and even-ness across the earth. As an alternative, they propose the term “patchy Anthropocene” to profile “the uneven conditions of more-than-human livability in landscapes increasingly dominated by industrial forms” (Tsing et al. 2019). Locating this concept firmly within the field of anthropology, they suggest that “that by broadening our notions of social relations into more-than-human space and time, anthropology may recapture what it does best: attending to specificity without being parochial” (ibid.). They refer to these patches or sites as “beings in landscapes” which takes account of the diversity of multi-species in local places. Patchy Anthropocene does not imagine a homogeneous human race nor an evenness of consequence from developments such as the industrial revolution or the Capitalocene. Instead, it is an intersectional, anthropological approach that topples the primacy given to human behaviour in the Anthropocene paradigm.

In considering the way nonhuman animals have been treated within the field of human geography, Geographer Chris Philol suggests that any inclusion of non-human creatures within the discipline has been conditioned by what he terms a “human chauvinism’. This implies that animals are either ignored or considered in the context of their relationship with humans. Philol (1995) notes that the trend has considered “animals as marginal ‘thing-like’ beings devoid of inner lives, apprehensions, or sensibilities, with little attempt being made to probe the often take-for-granted assumptions underlying the different uses to which human communities have put animals in different times and places”. Instead, Philol proposes an alternative paradigm which places animals in complex and nuanced relationships with humans.

Tsing et al. (2019) argue that the great acceleration of climate change is best countered through engagement with many small-scale and local rhythms. Their focus on the local patch is not confined to humans. Instead, they give voice to the “subaltern” – that is all the creatures that are considerate subordinate to humans in the Anthropocene contest. It includes animals as well as plants and insects who co-exist alongside humans in particular places. Tsing et al. regard the Anthropocene as “a wake-up call urging us to reinvent observational, analytical attention to intertwined human-and-nonhuman histories” (2019). They advocate a form of landscape literacy that engages with humans as well as non-humans in local places. Clifford Geertz’s webs of significance have been extended to include hitherto marginalised or suppressed voices (1973: 5).

Folklore and Local Patches (Places)

It is its engagement with local places, that makes folk-narratives such as rich resource when dealing with patchy Anthropocene. Three decades ago, Kent Ryden noted the significance of folklore for the expression of a sense of place (1993). While humans use maps to organise places geographically, maps do not express the wealth of human experiences in particular places. Maps are flat two-dimensional documents – consisting of lines drawn and re-drawn on paper. Maps locate places but they do not capture a sense of place. In the words of Shafak (2022: 1) “A map is a two-dimensional representation with arbitrary symbols and incised lines that decide who is to be our enemy and who is to be our friend, who deserves our love and who deserves our hatred and who, with sheer indifference”.

Ryden coined the term “invisible landscape” to capture the meaning that humans attach to places. Drawing on the folklore he had gathered in Northern Idaho, Ryden explored the dialectic between particular places and the representation of those places in folklore. A sense of place emerges from a fusion of time, memory and experience and that sense is expressed in traditional narratives or lore. In common with patchy anthropology, folk narratives emerge from specific (often small) places. Bateson (2021) argues that folk narrative “tends to be grounded in the hyperlocal, embodying intergenerational notions of place and community”. Christopher Tilley (1994: 34) suggests that narratives (along with movements and paths) help develop a distinctive sense of place.

The Gaelic tradition is replete with place lore which captures the spirit of particular “patches”. The importance of the local in the Gaelic tradition is best captured with reference to the concept of Dinnshenchus [place-lore] which references legends and incidents and/or attachments to particular places. Of the Gaelic narrative tradition, Seán Ó Tuama says that: “Down to our own day each field, hill and hillock was named with affection […]. There is a sense in which place finally becomes co-extensive in the mind, not only with personal and ancestral memories, but with the whole living community culture” (1985: 23). Woven together over several centuries, human and non-human narratives are linked with distinctive places and their geological activity. Moreover, traditional folklore has embraced the non-human or more than human world in those places.

Patricia Monaghan attributes the significance of particular places in Irish Gaelic folklore to the earth-centered (Pagan and Celtic) spirituality that prevailed in Ireland before the domination of Roman Catholicism (2010). Specific locations possessed “a particular power that is creative and regenerative” (ibid.). Moreover, “the shape of the earth’s surface creates innumerable nooks and crannies, each having a different quality about them and thus defining itself as a place having its own particular power” (ibid.). An energy or power emanated from different places throughout the Irish countryside and the human-place relationship was very significant.

In his work on human ecology, Ullrich Kockel (2014) emphasises that place is not where a relationship happens. Place is an intrinsic part of any relationship. Place matters and “not just as the construct it invariably also is, but as ontological datum” (ibid.). Moreover, it is ultimately ‘place’ that brings us together and enables relationships – and the activities they engender – to ‘take place’. “If we are at all, then there is a place at, in, from and towards which we thus are” (ibid.). This relational perspective puts place at the heart of our relations with others. Place is not a “third space” in Homi Bhabha’s (1994) sense. It is itself part of the relationship. “Place” is always an integral part of our various relationships.

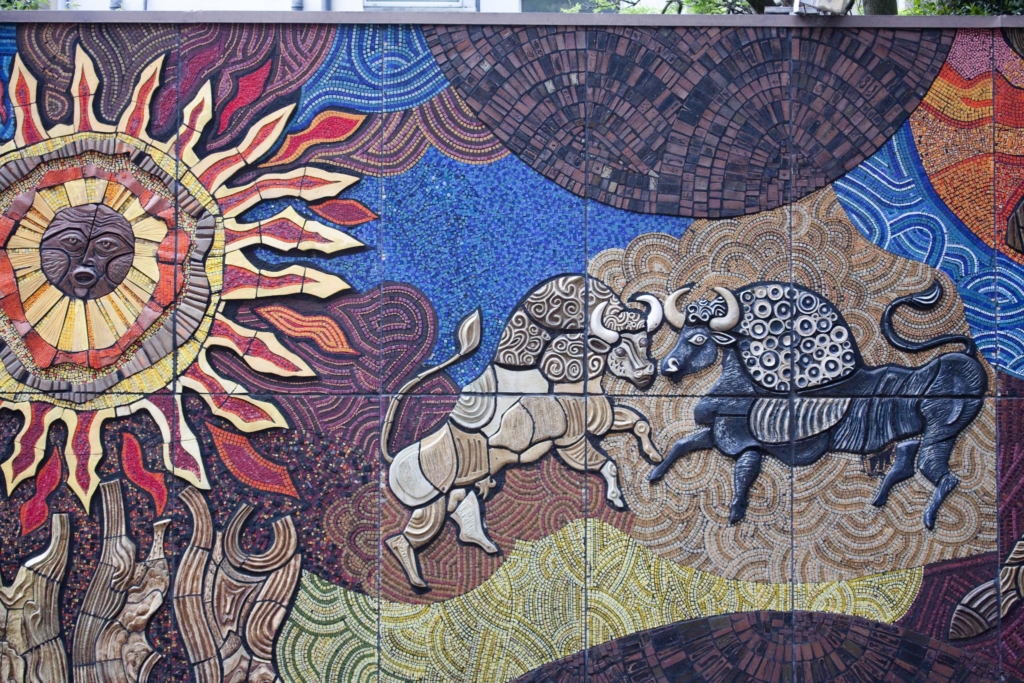

The Old-Irish tale of the Táin Bó Cualigne [The Cattle Raid of Cooley] is a strong example of the specificity of place in Gaelic folklore. From the Irish Ulster Cycle of Tales, the Cattle Raid of Cooley concerns a dispute between Queen Maeve and her husband King Ailill in the West of Ireland. When comparing their wealth, neither could outdo the other with one exception. Ailill had a great white bull for which Maeve had no equal. Having taking counsel, Maeve discovered a brown bull of equal strength in Cooley and requested the loan of it for a year. When ultimately refused the loan of the animal, the Queen despatched her fighting men to raid the bull. Ultimately, Maeve’s men brought the brown bull back to the Western region of Connaught.

Tain bo Cuailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley) · CC BY-SA 2.0 · File:Tain Bo Cuailnge Mural (Desmond Kinney).jpg · Created: 21 June 2009

Before long, the two bulls were engaged in battle. What follows in the narrative is a very detailed account of various bull organs falling onto the landscape. One of the more interesting aspects of the tale is how the landscape is changed as a result of the bull fight over a long trail. What is even more remarkable is that the journey of the bulls has been made without human intervention. The landscape has been named because of an interaction between two bulls and the site is altered from a place with no history and no cultural significance to one that is replete with meaning (Toner 2019).

An emphasis on a local place can sometimes spark a negative reaction. It can be seen as parochial or inward-looking. At worst, it can be mis-interpreted as a form of populism, nationalism or xenophobia – but in the words of Mairi McFadyen (2019): “Advocating for local culture is not about reifying places and forms of non-capitalism as untouched or outside of history as part of some sort of romantic hankering for paradise lost, it is to stand up against the destructive and homogenising forces of capitalist modernity”.

This is in the spirit of Scottish ecologist Patrick Geddes who advised people to ‘think global and act local’ (MacDonald 2020).

An emphasis on local place is very much in keeping with the Gaelic concept dùthchas/dúchas (loosely translated as heritage from below) which implies a strong relationship with the land. This contrasts with another Gaelic word Oidhreacht (loosely translated as heritage from above) which implies a relationship with place that is directed by the government or state. Speaking from a Scottish-Gaelic context, Alan Riach (2021) suggests that “Dùthchas is the word that describes understanding of land, people and culture” in a Gaelic context. In the words of James Oliver it is an “ontological dynamic of embodied experience and terms and emplacement (…), and complex entanglement (…) with relationships of belonging and dwelling, heritage and inheritance, a human ecology with ‘place’.”

Four Multi-Species Models

Gaelic folk-narratives offer several different models of species living together in particular places. Firstly, I’d like to draw on the story of the renowned warrior, Fionn Mac Cumhail. As a young boy, Fionn was mentored by a wise poet named Finnegas who lived on the banks of the river Boyne. Finnegas was renowned for his deep knowledge of nature – animals, forests, rivers, the wind and the rain. As recompense for this teaching, Fionn collected firewood and cooked. Fishing was the only task that was forbidden to Fionn.

It had been foretold by the Druids that on rare occasions a salmon of knowledge would be found at Connla’s well. The well was surrounded by seven hazelnut trees which contained immense wisdom. Once the nuts fell into the water, the salmon would feed on them and be imbued with all the knowledge of the world. At that point, a red spot would appear on the flesh of the salmon. Finnegas spent many years trying to catch this salmon and was overwhelmed with joy when, one day, he caught a salmon with a red spot on its belly. Immediately, he asked Fionn to gather firewood and cook it. He warned him not to taste it but did not explain the reason for this. It has been foretold that whoever ate the first bite of the fish would gain the knowledge of the salmon.

While he was cooking the fish, Fionn burned his thumb, and instinctively put it in his mouth. This immediately imbued him with the knowledge of the salmon. When the poet returned, he saw the wisdom in the young boy’s eyes. Despite his disappointment, he suggested that Fionn finish eating the fish and advised him that whenever he put his thumb in his mouth, the knowledge of the world would be revealed to him. (As an aside, isn’t it interesting that the ancient storytellers didn’t need to wait for the discovery of Omega 3 before they knew oily fish was good for the brain!).

In this folk narrative, the different species worked together like a chain of connectivity. Nine hazel nut trees grew over the well. The nuts on the trees contained wisdom. As the nuts fell into the water, they were eaten by the salmon who then swam downstream. The human who ate the salmon was endowed with gifts of wisdom, inspiration and knowledge. When humans died, they decomposed into the land and it was from the land that the trees grew. What is even more interesting about this narrative is that the gift of knowledge was not limited to humans. As Meg Bateman notes, the intuition gained by Fionn Mac Cumhail when sucking his thumb was not that of an individual but a universal intuition “sought by poets composing in the dark, [it] is the knowledge drawn up through wells, roots, and rivers of the mystery of regeneration. This is an understanding that life is wholly dependent on the earth” (Bateman 2009).

A later episode in the Fionn Mac Cumhail narrative reveals a second model of co-existence which is shape-shifting between human and animal. When the legendary warrior, Fionn Mac Cumhail, grew up, he loved to hunt at Slievenamon in Co Tipperary. It was while hunting there that he met his wife, Sadhbh. She had been turned into a deer by a druid whom she had refused to marry. Although she had the figure of a deer, Fionn’s hounds recognised her as human. Fionn brought her home. She was transformed back into a woman the moment she set foot on Fionn’s land, as this was the one place she could regain her true form. Soon, Sadhbh was pregnant. When Fionn was away defending his country, the druid returned and seething with envy, he turned Sadhbh back into a deer, whereupon she vanished. Fionn spent a lot of time searching for her, but to no avail.

Years later when out with his hounds, Fionn found a fawn in the forest. He recognised the animal as his own son with Sadhbh. Once he brought him home, the fawn turned into a boy whom Fionn named Oisín (meaning little deer). Oisín would later become one of the greatest of the Fianna. Bateman summarises the movement between the species as follows: “The hero, Fionn, originally a god, changes shape as a dog, deer or man; his nephews are dogs, one of his wives is a deer and his son, Oisean is part-deer” (2009). In many traditional Gaelic folk narratives, the relationship between Gods, humans and animals was blurred. Humans could change into werewolves, hares, insects etc. Shapeshifting occurred frequently and shapeshifters passed through a range of animal forms, insects, birds and mammals. It seems that knowledge of and identification with the different species was regarded as an advantage for those who experienced it and consolidated relationships between the different species.

The relationship between humans and other species was celebrated in poetry as well as in narrative. There is a very famous poem in medieval Irish literature called Pangur Bán. This poem was penned in the 9th century at or near Reichenau Abbey in Germany. It was written by an Irish monk about his cat, Pangur Bán. The poem describes not only the harmonious existence between monk and cat but also their parallel activities. Their relationship between human and animal is equal. The poet compares the cat’s happy hunting with his own scholarly pursuits. While the cat hunts for mice, the monk pursues an ancient manuscript for meaning.

Seamus Heaney (2006), the Irish Nobel Laureate translated this poem into English. Heaney’s translation captures the equal relationship between monk and cat:

Pangur Bán and I at work,

Adepts, equals, cat and clerk:

His whole instinct is to hunt,

Mine to free the meaning pent.

The human and animal are engaged in parallel pursuits. Once he observes the mouse, the cat pounces on it. In the same way, the monk pounces on lines once he understands their meaning. During their shared pursuit, the monk gazes piercingly on the text while the cat keeps his eye fixed on the wall. When the cat springs on the mouse, it exults in the kill. The monk is equally ecstatic when he captures hidden meaning. Each of the two creatures is focused on their pursuit and there is no rivalry between them. They are kindred spirits. In the words of Heaney (2006):

Day and night, soft purr, soft pad,

Pangur Bán has learned his trade.

Day and night, my own hard work

Solves the cruxes, makes a mark.

Matching behaviour between humans and animals is also evident in traditional Irish-Gaelic proverbs. Many Irish traditional sayings imply parallels between the natural environment and humans. In the following proverb, for example, there is a warning to beware the silent human:

Is iad na muca ciúine a itheann an mine.

[‘tis the silent pigs that eat the meal.]

Sometimes human actions are compared to animal ones. One might say of humans, that they are:

Ag ithe’s ag gearán ar nós cearc goir.

[Eating and complaining like a hatching hen.]

A human who is too eager is compared to a horse:

Ní deacair capall umhal a sporadh.

[The willing horse doesn’t need much spurring.]

A well-known proverb implies that humans can act like insects:

Aithníonn ciaróg ciaróg eile.

[One beetle recognises another.]

Plants also feature as in the following example which compares young children with saplings:

Is minic a thánag an tsal nar mheas gurb í d’fheocadh.

[The sapling expected to wither often makes good.]

Michael Newton calls this process human-nature mirroring (2019). He refers to parallels perceived between humans and trees in the Gaelic world. The anatomy of the tree was seen as comparable to the human body and the same Scottish Gaelic terms are used for the human body and trees alike. People are often described with tree metaphors. For example, the phrase: “It was in the timber” is used to describe something hereditary. The importance of rearing a child well is captured in the phrase: “bend the sapling and the tree won’t defy you”. An aggressive person is compared with the antagonistic ash: “The way of the wild ash befell him”. These examples demonstrate agency on behalf of not just humans but also nature. The parallels are not simply a projection of human personality traits onto the natural world but go in both directions.

An Ecological Reading

These four models serve to illustrate that the pre-Christian Gaelic mindset encoded a particular way of thinking about humans and nature which was multi-species rather than anthropocentric. In the traditional Gaelic world, humans were not separated from other species. There was an ecological balance between all entities. A key feature of the dùthchas/dúchas concept is interconnectedness. Paul Meighan explains, “the importance of this concept of the connectedness and inter-relationships between land, people and culture, held in the word ‘Dúthchas’, cannot be overestimated” (2022). It captures the way that land, people and community, past and present, are interlinked – connections which are maintained by practices, language and other means.

Deborah Bird Rose uses the concept of kinship with similar intent. This concept, she says, “situates us here on Earth, and asserts that we are not alone in time or place: we are at home where our kind of life (Earth life) came into being, and we are members of entangled generations of Earth life, generations that succeed each other in time and place” (2011: 50). Humans are only one species that live in kinship with others. This multispecies kinship is the glue that binds nature together. We are dependent on one another, vulnerable to one another and responsible for one another (Doreen and Chrulew 2022). Keith Basso points to a similar cosmology among Native Americans when he notes that “dwelling is said to consist in the multiple ‘lived relationships’ that people maintain with places” (1996: 54).

Patricia Monaghan (2010) compares the spiritual (rather than religious) dimension in the Gaelic worldview to that of Indigenous peoples. She claims that “the traditional Irish worldview derives, as does the Native American, from a vision of nature as immeasurably holy, understood through story and ritual in specific rather than generic places” (Monaghan 2010). Like dùthchas/dúchas and kinship, this is a holistic perspective. It is an understanding of nature that contrasts sharply with the science. It believes that the earth is alive and concurs with the Gaia hypothesis advocated by Lovelock and Margulis in the 70s (Lovelock 1972; Lovelock and Margulis 1974). The Gaia hypothesis (named after the Greek Earth goddess) suggests that all living organisms on earth interact with each other to create synergetic and self-regulating system. The earth is continually in a process of becoming.

My reflections on the multi-species nature of Irish folklore draw on the Irish philosopher’s Richard Kearney’s concept of “diacritical hermeneutics” (2011). Kearney understands hermeneutics as the art of deciphering multiple meanings. In its most basic sense this relates to the human capacity to have ‘two thinks at a time,’ as James Joyce said. More precisely, it refers to the practice of discerning indirect or tacit allusive meanings, of discerning another sense beyond or beneath the obvious. Monaghan argues that “many Irish folk tales encode environmental understanding necessary for survival in subsistence economies and, in some cases, for survival of the planet as well” (2010).

It is a form of knowledge that has emerged from local engagement with particular places. It is local rather than universal. The American Indian focus on the local is described by Nabokov in the following terms: “over there something wondrous or unexplainable or terrifying happened; right there some spark was struck between the everyday and the extraordinary, creating a memory so bright that some still go there to pay respects or conduct rituals or contact the spirits” (Nabokov 2006: 3). Very often this form of knowledge is disregarded as unscientific since it is imbued with cultural values.

Critics might argue that this kind of ecological reading is a form of anachronism – i.e. that it is simply a projection of our own, modern knowledge and anxieties about climate change back in time and that we are attributing environmental anxieties to humans in the past. But as Hennig and his colleagues propose “it is certainly reasonable to assume that also premodern societies experienced environmental and climatic changes, even though these were of a different quality than the massive transformations on a global scale occurring today” (2013: 26). Arguments against this kind of ecological readings of folk-narratives imply that any and every story has a fixed and limited meaning. This denies the role of the reader to interpret the story from their own perspective. Given the current climate crisis, it is surely legitimate to read ‘contemporary ecological issues into the medieval past so that we can read out of medieval texts ideas that inform our responses to the world that we live in now’ (Abram 2019: 38) and these are not just any stories – but narratives that have emerged from our local places, from our dùthchas/dúchas.

Silver Branch Perception

Drawing on our traditional folktales, I believe we should adopt an approach that Scottish activists McFadyen and Sandilands call “cultural darning and mending” (2021). They describe this as a “playful approach to cultural activism” or a future-orientated creative ethnology that engages with our folk narratives, our placelore and traditional local knowledge. In linking to the past, we ‘re-member’ (McIntosh 2003) a dùthchas/dúchas -grounded relationship with the land – and raise consciousness about what was lost during the process of Anglicisation and colonisation in Ireland (Nic Craith 1992). Part of this “cultural darning and mending” involves re-visiting our traditional folk-narratives and reading them ecologically. It could encompass activities such as revised folk-narratives for adults or children, mapping activities, collage etc.

Our reclamation of traditional folk narratives could potentially bring about a renewed and fresh perspective on the environment what the Irish eco-philosopher John Moriarty calls a “silver branch perception” (2005). The concept of “silver branch perception” is drawn from Irish mythology and refers to a medieval Irish tale called Imram Bhrain (The Voyage of Bran) which is narrated in the 12th century Lebor na hUidre (Meyer 1895). In this folk-narrative, King Bran mac Feabhail got up in the middle of a great feast and walked to the forest. Normally fearless in battle, the king found himself strangely unsettled and began to hear music from a silver branch, but nobody was playing. The music was coming from the Otherworld. As he listened to the music, the King’s perspective changed and previous victories in battle suddenly seemed insignificant. The King then returned to the feast and saw a woman from the Otherworld who invited him to come to her land.

The following morning, Bran and his army set sail for the Otherworld. After three days and nights, the sea transformed into a land filled with flowers. There they encountered Manannán Mac Lir, the God of the Sea who was singing with joy. Manannán bestowed the gift of a silver branch with golden apples on Bran and all were bewitched. When the singing ended, Manannán disappeared and the beautiful land was transformed back into water. Once again, the sea was dull and grey and smelled bitter. Bran and his army returned home. Bran came to realise that the Otherworld he had been invited to was simply another perspective on his own world. The experience gave Bran a heightened perception of the world in all its forms.

Alastair McIntosh (1998) suggests that this silver branch (bough) perception is the branch of apple blossom given by fairies to enable humans to pass into musical and poetic realms. The imagery is not confined to Celtic folk narrative. A similar feature occurs in the Aeneid during Aeneas’s quest to find a golden bough to gain access to the Underworld. When Aeneas begins his descent into the Underworld, the golden bough is shown to Charon who then allows the visitors to enter the boat and cross the Stygain river.

While the narratives differ in detail, the key feature remains the same. Silver or Golden branch perception enables a wider perspective on relationality within the universe. It is not bound by logic but is open to different insights beyond the rational. It engages the senses as well as the mind. Silver Branch Perception represents a transition. It involves a heightened awareness of the oneness or holistic nature of the world. It “is a shift towards an acknowledgement of a reverence in being, to the wonder inherent in the living world” (Ward 2022: 6). In consequence of this change in perception, “what once appeared ordinary becomes extraordinary” (ibid). Moriarty described this enhanced perception as ‘mirabili’. This is a way of knowing the world that acknowledges the strangeness of reality but does not attempt to explain it or master it. It involves a new way of looking at the earth, and a new, non-hierarchical relationship between humans and other species.

Frank MacEowen describes silver branch perception as “a way of seeing the entire Ecology of the world, natural and spiritual” (2013). It requires breaking the habit of separating the human from the animal, the societal from the personal and the spiritual from the mundane.

Silver branch perception is a journey that allows us to see all of nature as sacred and everywhere as “a place of spiritual practice”. In his Invoking Ireland, Moriarty describes “silver branch perception” as a gift that the Irish lost as they tried to dominate nature (2005: 150). “Brutally, as though it didn’t exist, we felled forests, we killed and slaughtered calves, we set fire to whole mountainsides of heather and furze”, but it is perhaps a skill that could be reclaimed if we were to revisit our traditional folklore with ecological eyes (ibid.).

Folklore and Ecological Diversity

Although the concept of “silver branch perception” it not explicit in it, a recent report from NatureScot (2021) draws on Gaelic folklore to make the case for a revised perception of the environment and its many species. Examining Gaelic placenames in the landscape, folklore, stories, poems and songs, the author, Roddy Maclean finds a wealth of evidence about the ways in which the natural world was appreciated by traditional Gaels. They valued clean air, fertile soils and timber as well as recreational and spiritual benefits. The report identifies hundreds of references to ecosystem services such as food, timber, medicine, fuel and fibre.

Pointing to medieval narratives of the Fianna, the author notes the significance of red deer as well as highland cattle to the way of life of the Highland people (MacLean 2021: 16). He profiles the strong tradition of stories of seals and the seal women who visited the shores. McLean proposes that stories like these indicate the “strong connection between humans and the wild through transmogrification” but also a “barrier between the human world and the wild, which can only be crossed by certain people at certain times, and sometimes in just the one direction” (2021: 44).

While the relationship between humans and animals was very significant in these medieval Gaelic tales, it also extended to plants. In many tales from the Fianna, the excellent health of the women was attributed to the “boiled tops of hazel” they ate from the treetops. The same food was shared with sheep and goats (McLean 2021: 56). The oak tree was used to make weapons and yew or ash were planted in woods with the intent of making bows (McLean 2021: 57). McLean profiles the knowledge that traditional Gaels had regarding medicinal uses of plants and animals. Such knowledge “can inform the argument about protection of habitat, where the existence of a greater species diversity can be argued from a cultural, as well as natural, perspective” (McLean 2021: 43).

The Celtic God of the Sea and the Broigher Gold. CC BY-SA 2.0

What is interesting from a folk narrative perspective is the extent to which the report drew on traditional lore to suggest policy changes. In particular, the author argued that Gaelic lore could bring a Highland/Gaelic perspective to conversations about nature in Scotland. It could bridge the gap between Gaels and non-Gaelic speakers and bring a traditional perspective to the contentious rewilding debate in Scotland, which has largely been dominated by an Anglo-centric worldview. One of the report’s recommendations was to establish a project to research “some of the iconic places in Gaelic literature” and analyse them “for their botanical and zoological diversity and environmental health in the current era, in the light of the descriptions made of them by Gaels in the past” (McLean 2021: 76).

Conclusion

Initiatives such as these offer hope in a time of climate crisis. The sense of despair about the future of the planet implied in the Anthropocene concept is decades old. In 1972, folk collector Alan Lomax wrote that “a grey-out is in progress which, if it continues unchecked, will fill our human skies with smog of the phony and cut the families of men off from a vision of their own cultural constellations” (1972). Lomax was referencing the process of globalisation which was flattening out local cultural perspectives in favour of “mass-produced and cheapened cultures everywhere” (Lomax 1972). In consequence, humans lose ways of living on and with the planet that will deprive future generations of the possibility of life itself. It was to counter this disillusionment that Anna Tsing and others designed the concept of ‘Patchy Anthropocene’ (2019). Instead of dealing with helplessness on a global scale, activities could zone in on specific places with an attitude of optimism and ambition.

Although catastrophic in consequences, the current anthropogenic concept can be infused with a sense of hope. As the writer, historian and activist Rebecca Solnit (2023) has said: “We cannot afford to be climate doomers”. Drawing on the experiences of Indigenous peoples who have previously faced deforestation and annihilation, one can imagine local solutions which are permeated with a radical courage that is “directed towards a future goodness that transcends the current ability to understand what it is” (Lear 2008: 103). This solution will not be achieved by a single mode of knowing favoured by Western imperialists. Instead, it will involve different modes of knowledge. Although alternative ontologies such as dùthchas/dúchas have been diluted/flattened by the colonial project, these Indigenous modes of knowledge are crucial if we are to invest localities with relevant thinking. Sophie Strand says: “A myth is a patch of soil where we can plant the best practices of a community: how to relate to each other and to our shared ecosystem” (n.d.). Let us revisit our traditional folk-narratives to build a better future.

This article is published under the creative commons licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

Bibliography

Abram, Christopher 2019. Evergreen Ash. Ecology and Catastrophe in Old Norse Myth and Literature. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Basso, Keith 1996. Wisdom sits in Places: Landscape and Language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Bateman, Meg 2009. The landscape of the Gaelic imagination. International Journal of Heritage15 (2–3), 142–152.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13527250902890613

Bateson, Callum. 2021a. Folklore and the climate crisis: Reading Beara as an Anthropocene patch with Máiréad Ní Mhíonacháin. Networking Knowledge 14(2), 110-123. https://doi.org/10.31165/nk.2021.142.644

Bhabha, Homi 1994. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

Doreen, Thom van and Chrulew, Mathew eds 2022 Kin: Thinking with Deborah Bird Rose. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press

Geertz, Clifford 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Heaney, Seanus 2006. Translation of Pangur Bán. Online. Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/48267/pangur-ban

Hennig, Reinhard, Emily Lethbridge and Michael Schulte 2023. Combining Ecocriticism and Old Norse Studies: Opportunities and Challenges. In: Ecocriticism and Old Norse Studies: Nature and the Environment in Old Norse Literature and Culture edited by Reinhard Hennig, Emily Lethbridge and Michael Schulte. Turnhout: Brepols, 11-36.

Kearney, Richard 2011. What is diacritical hermeneutics? Journal of Applied Hermeneutics.

https://doi.org/10.11575/jah.v0i0.53187

Kockel, Ullrich 2014. Towards an ethnology beyond self, other and third: toposophical explorations. Tradicija ir dabartis 9, 19-40. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12259/48833

Lear, Jonathon 2008. Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lomax, Alan 1977/1980. Appeal for cultural equity. African Music, 6(1), 22–31.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/30249739

Lovelock, James E. 1972. Gaia as seen through the atmosphere. Atmospheric Environment 6(8), 579-580. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-7944-4_2

Lovelock, James and Lynn Margulis 1974. Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: the Gaia hypothesis. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 26 (1-2), 2-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2153-3490.1974.tb01946.x

MacDonald, Murdo 2020. Patrick Geddes’ Intellectual Origins. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

MacEown, Frank 2013. Places Named and Tended. Online. Available at:

https://vitalxrecognition.wordpress.com/2013/08/18/places-of-practice/

McFadyen, Mairi 2019. Songs and singing: a wellspring for the future. Online. Available at: Bella Caledonia for The National, 22 December. http://www.mairimcfadyen.scot/blog/2019/12/27/songs-amp-singing-a-wellspring-for-the-future-bella-caledonia-column-december-2019

McFadyen, Mairi and Raghnaid Sandilands 2021. Cultural darning and mending: Creative responses to ceist an fhearainn/the land question in the Gàidhealtachd. Scottish Affairs 30(2), 157–177.https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.2021.0359

McIntosh, Alastair 1998. The gal-gael peoples of Scotland: On tradition re-bearing, recovery of place and making identity anew. Online. Available at: https://www.alastairmcintosh.com/articles/1998_galgael_htm.htm

Maclean, Roddy (MacIlleathain, Ruairidh) 2021. Ecosystem Services and Gaelic: a scoping exercise. Inverness: NatureScot.

Meighan, Paul 2022. Dùthchas, a Scottish Gaelic methodology to guide self-decolonization and conceptualize a kincentric and relational approach to community-led research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21, 1–14.

https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221142

Meyer, Kuno 1895. The Voyage of Bran. Online. Available at:

https://sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/vob/index.htm

Monaghan, Patricia. 2010. “Calamity Meat and Cows of Abundance: Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Irish Folklore”. Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, 19(2), 44-61.

doi: 10.3167/ajec.2010.190204

Moriarty, John 2005. Invoking Ireland. Dublin: Lilliput Press.

Moriarty, John 2011. Nostos. Dublin: Lilliput Press.

Nabokov, Peter. 2006. Where the Lightning Strikes: The Lives of Native American Sacred Places. New York: Viking.

Newton, Michael 2019. Warriors of the Word: The World of the Scottish Highlanders. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Nic Craith, Máiréad 1993. Malartú Teanga: an Ghaeilge i gCorcaigh sa Naoú hAois Déag. [Change of tongue: Irish in Cork in the nineteenth century]. Bremen: ESIS.

Nic Craith, Mairéad 2023. “Gaelic folklore for a multi species future”, Bella Caledonia, https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2023/08/23/gaelic-folklore-for-a-multi-species-future/

Oliver, James 2021. Acknowledging relations: ditches, seanchas and ethical emplacement. In: The Commonplace Book of ATLAS, edited by Emma Nicolson and Gayle Meikle. Portree: ATLAS Arts, 30–33.

Ó Tuama, Seán 1985, Stability and ambivalence: Aspects of the sense of place and religion in Irish literature. In: Ireland: Towards a Sense of Place, edited by Joseph Lee. Cork: University Press, 21-33.

Philol, Chris 1995. Animals, geography, and the city: notes on inclusions and exclusions. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 13(6), 655-681.

https://doi.org/10.1068/d130655

Riach. Alan 2022. Dúthchas: The word that describes understanding of land, people and culture. The National,

https://www.thenational.scot/news/18306403.duthchas-word-describes-understanding-land-people-culture/

Rose, Deborah Bird 2011. Wild Dog Dreaming: Love and Extinction. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Ryden, Kent 1993. Mapping the Invisible Landscape: Folklore, Writing and the Sense of Place. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Shafak, Elif 2022. The Island of Missing Trees. London: Penguin.

Solnit, Rebecca 2023. We can’t afford to be climate doomers. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jul/26/we-cant-afford-to-be-climate-doomers

Strand, Sophie n.d. An Introductory Note to Rewilding Mythology

https://advaya.life/articles/an-introductory-note-to-rewilding-mythology

Tilley, Chris 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg.

Tsing, Anna, Nils Buband, Elaine Gan and Heather Swanson eds. 2017. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press; 3rd ed.

Tsing, Anna, Andrew Mathews and Nils Buband 2019. Patchy Anthropocene: Landscape structure, multispecies history, and the retooling of anthropology. Current Anthropology 60(20), 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1086/703391

Toner, Greg 2019. Myth and the creation of landscape in Early Medieval Ireland. In: Landscape and Myth in North-Western Europe, edited by Mathias Egeler. Turnhout: Brepols, 79–97.

Ward, Nora 2022. Ontopoetics and the Environmental Philosophy of John Moriarty, Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology 27(1-2): 1-24.

https://doi.org/10.1163/15685357-20211210