Anarchy in the GCC

A remarkable social event will occur in Glasgow this weekend – Scotland’s Second Summer of Punk. On the surface, the ‘Punk All-Dayer’ may seem a sorry excuse for the pensionable to relive their rebellious youth, all within the safe confines of Bellahouston Park, a figurehead of Glasgow respectability and the seeming antithesis of everything that ‘punk’ stood for. The credibility of the festival line-up too may also raise a few eyebrows due to a lack of many original band members, with some acts now approximating something closer to a tribute act than their 1977 heyday.

However, it is the group names themselves and what they represent that elicit intrigue due to their unique history within Glasgow. The most notorious in the festival line-up are the two groups who were once firmly instructed nearly 50 years ago – by the precise organisation now welcoming them back – that they would never be allowed to play in the city again. Yet here they are, now performing at one of the city’s summer musical highlights. These two bands are the Sex Pistols and the Stranglers. What has changed?

Of course, variations of these two groups have since played in Glasgow after 1977, although not in such an illustrious setting. And anyone who has seen their various iterations over those years will know that little of the ferocity of their performance has been diminished. Their appreciative audiences are still as unruly as ever and the power of the songs themselves have too little dimmed over that time either. While Radio Two may occasionaly play a few tracks, Bodies by the Sex Pistols is still unlikely to be heard on Cash in the Attic any time soon. Sex Pistols undoubtedly still have the ability to shock.

However, they are of a previous generation and that generation is, as much as we hate to admit it, of the past. And…they are now a little long in the tooth and age is seemingly not now seen as a threat to our society, at least not by those with guitars anyway. Old age is what has significantly changed since December 1976. Despite politicians in their 50s, 60s and 70s seemingly being hellbent on destroying the world, our elders singing songs to a group of equally aging fans (myself included) is apparently now safe and fine.

But…singing a song while you are young to others of a similar age is not fine. There needs to be a little qualification here: it is a certain type of young person, singing a certain type of song to a certain impressionable youthful generation that is what’s not fine. Anyone who has read a newspaper, watched television or used social media over the last month will be very familiar with the Irish group Kneecap and the calls for their exclusion at another certain Glasgow festival this summer. And their treatment is a very similar story to those of both the Sex Pistols and Stranglers in Glasgow.

Pop music is the greatest social democratisation of art, possibly ever, and its emergence offered an unique platform to its creators to air their views, which, despite huge changes, still exists today. It’s one of the few opportunities for young working-class youth to have their voice heard by so many and in such an egalitarian manner. And it’s one that offers huge power and responsibility. John Lennon was perhaps the greatest recipient and proponent of that power. While the press and public loved the humorous moptop press conferences of the early 1960s, the politicised Lennon of the late 60s and early 70s, commenting on the political hot potatoes of the day, drew attention from both fans and a society concerned by interference from those deemed not qualified to do so. Lennon’s role as a pop star offered him significant political and social influence over a generation of not just Beatles fans, but young people more widely.

Lennon’s generation and his affiliations with revolutionary politics are now, much like today’s Sex Pistols, just a part of history. They’re not preaching to the youth. They are no longer a threat because the youth of today have little interest in listening to an older generation. Kevin Macdonald’s recent (and excellent) One to One documentary on Lennon’s early 70s revolutionary politics is rendered little more than social history. Its message is still valid but neutered because it is now part of the establishment and as such there’s little threat of today’s young using it to hold their elders to account.

As has always been the case, the youth of today clearly want to listen to someone within their own generation who has not yet been tainted by authority. They want their voice heard, they want to know about injustices and they want to act upon them. They are waiting for a figurehead to speak for them and this is the real threat to society. Young, mostly working-class, youth with a voice and a will to change society will always be a threat. That hasn’t changed. Like Lennon’s message, the Sex Pistols of today are neutered by an audience who are no longer willing to change. The Sex Pistols and Stranglers history within Glasgow is a warning to the establishment. It’s a warning of the damage that trying to prevent your youth from being heard can do to your culture.

The beginning of their story in Glasgow is of course, the 1st of December 1976, and one of television’s most notorious live events: the Sex Pistols being interviewed on London television by Bill Grundy. It’s simple enough to take the viewpoint that the proceeding outrage was caused by the band’s swearing but this doesn’t adequately convey societies fear. The underlying outrage was not that the band swore on TV – it was they were seen to not care while doing so. There’s a difference. The band had revealed the wizard behind the curtain – that a dissatisfied youth don’t need to be controlled or scared by authority – and the youth then, as today, had the growing division between generations reflected back at them. From that moment, the band were seen as a threat that needed to be immediately curtailed.

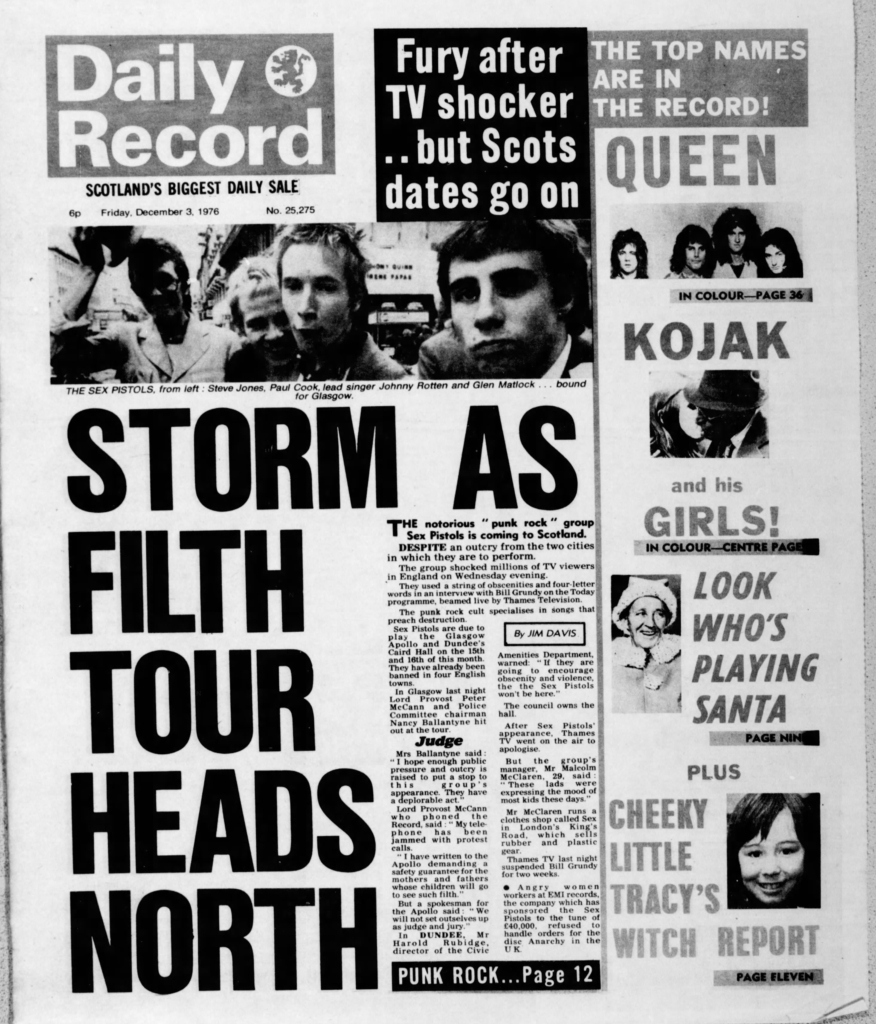

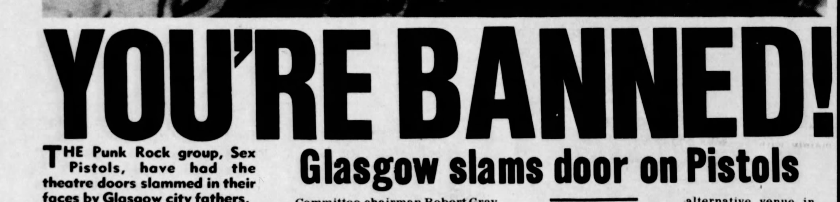

In the following media storm Glasgow’s Daily Record – and the then Glasgow District Council – were suddenly made aware that the group were actually due to play at the Apollo Theatre two weeks later. Despite having played in Dundee just over two months previously with no incident, the entire establishment preceded to confront the band with ‘extreme prejudice.’ The Daily Record’s front page on the 3rd of December was emblazoned with ‘Filth Tour Heads North’. For the next 5 days, the paper had a full-on assault on the dangers the group might bring to Glasgow’s youth until the headline finally read: ‘You’re Banned – Glasgow Slams Door on Pistols’. Followed by:

“The Punk Rock group, Sex Pistols have had the theatre doors slammed in their faces by Glasgow city fathers…Yesterday the District Council Licensing Committee used a condition in the theatre’s licence to close the Apollo on that night. Committee chairman Robert Gray said ‘We have enough problems in Glasgow without importing yobbos’. Apollo manager Jan Tomasik said ‘They can do this at any time for ‘the preservation of the public peace. There is no way I am going to fight the committee. I have to operate 364 other days of the year.”

The saddest aspect of this ‘storm’ was how the media and Council colluded between themselves. Nobody in the council had actually even heard the band perform, nobody had listened to them – either literally or to what they clearly had to say about society. The event was shut down using a rarely used ‘get out’ clause in the Theatre Act, much to the dismay of the venue, who were firmly standing on the side of Glasgow’s culture.

Jan Tomasik (manager, Glasgow Apollo. Evening Times, 1976): ‘It would appear that our City Fathers have judged the Sex Pistols without ever having seen them on stage or having heard their ability. It would appear that the Lord Provost has no faith in the moral values of our city’s fine youngsters.’

The irony is this furore is what made the band so huge and accelerated their ability for social change, as guitarist Steve Jones commented, “Grundy didn’t just catapult us to a new level of fame, it took the whole thing into another dimension in a way that was hard to grasp…the best way I can think of describing how it felt is like in Star Trek when they are flying along normally in space, then Scotty presses the warp speed button and, whoosh.”

Similar processes to thwart performances were used UK-wide to deter what was known as ‘the Anarchy Tour.’ While the Sex Pistols were later forced to perform under a series of pseudonyms, ‘Punk’ in general was left to its own devices. In fact, it slowly blossomed. By 1978, even the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin were stripping back their sound to appeal to the ‘Year Zero’ ethos. By 1981, 50% of the UK music chart would be informed by 1977 punk, or those directly inspired by it.

Glasgow was another matter and ‘punk’ there had to be stopped at all costs. This was pursued relentlessly.

The prescribed narrative is that a City Hall concert by the Stranglers on the 22nd June 1977 led to ‘punk being banned’, due to the ‘rioting’ of fans and the ensuing press ‘outrage’. However, no evidence for this reality exists. Ironically, Glasgow District Council were fearful of the negative impact that potential Council-sanctioned further ‘bans’ would have. They allowed the concert to proceed and the press instead created the ensuring drama. Despite the bluster of ‘never again to punk’ and other out-of-context quotes from the council, there was no ‘ban’ and instead the decree that groups would be ‘judged individually’. And this is where events turn a little darker and wording has to be carefully guarded.

The subsequent six months of ‘punk’ in Glasgow contain multiple press stories and accounts from band management, promoters and group members; all very truthfully recounting stories of being banned from performing at a venue. I’ve gone through almost every Daily Record, Evening Times and Herald from 1977 and have handfuls of articles all confirming this. However, I’ve also gone through the entire Glasgow District Council archives from that period and the cupboards are virtually bare. There appears to be little official to corroborate these claims and reporting but there’s absolute certainty that venue owners were told they ‘would lose their licence’ if they allowed a punk band to play. I’ve spoken to nearly 100 people involved in the 1977 Glasgow music-scene during this period and I truly believe ‘threats’ of venues losing their licence were real. So, why is there a discrepancy between their accounts and what lies in the officialdom relating to them?

It should be noted that there were two differing types of licences used for venues allowing live music to be performed. One was the aforementioned Theatre Licence, an obligation for large venues such as the Apollo. This was a very strict legal requirement for a council officials to ‘sign off’ a theatre’s daily performance. For smaller venues there was the Entertainment Licence that would be renewed less frequently. The latter could arguably generate a potential conflict of interest for ie. police or Council officials being responsible for maintaining the livelihood of a venue proprietor’s business. It’s almost certain that in a small number of cases that this power was abused. And fear of ‘punk’ was certainly an excellent opportunity for this.

The net result of this combination of official and less official restricting of ‘punk’ music – by the Council and the media – was a creative still-birth within Glasgow. It was not just a small group of punk-bands who were denied the opportunity to perform and grow artistically; the infrastructure surrounding them was equally affected. Manchester, a city with similar socio-economic situation to Glasgow, embraced the Sex Pistols – they performed four times in 1976 (including two of the eventual seven Anarchy Tour dates) and also appeared on Granada Television. There’s a clear line of trajectory from their first Manchester appearance to that city’s later hugely significant music industry; it’s inarguable that Manchester’s music industry was responsible for the city’s financial and cultural rebirth after its late 70s post-industrial decline. The city acknowledges this abundantly with streets, buildings and venues dedicated to its punk heroes. Politicised youth and music has the power to change minds, and it can change a city.

Glasgow certainly caught up musically. Simple Minds laid many of the foundations that would lead to Glasgow’s European City of Culture status, and Postcard Records also brought significant media attention to the city. However, it’s abundantly clear that nearly two years of potential growth, between 1977 and 1979, were lost due to extremely repressive actions by the city towards its own youth. Another solid argument can be made that the reluctance to invest in musical venues, recording and rehearsal facilities, and most especially in the promotion of music itself, is what led to Scotland’s later near dominance within ‘DIY’ and ‘Indie Music’ – would Belle and Sebastian and Franz Ferdinand have been created without that struggle? However, it’s equally arguable – and heartbreaking – that the absolute Calvinistic approach towards Glasgow’s ‘punk’ music in 1977 ensured that many mostly working-class kids never had the opportunity to create and leave a legacy that enriched their city, and that’s culturally criminal.

This weekend is an excellent opportunity for Glasgow City Council, the media and politicians across all sides to reflect on the mistakes from 1976 and 1977. Listening to the young reaps rewards. There’s very little evidence that music will cause political revolution but there’s a huge amount of evidence that music will create and enrich people’s lives – financially and culturally. Don’t fear your youth, embrace them and help them as it will clearly help everyone. Don’t wait until 2075 and hold a Kneecap in the Park. Do something now. As to this weekend’s festival, it’s going to be fantastic.