Good COP Bad COP: Big Oil, Cambo and Media Climate Lies

Christopher Silver on the extreme weather of the climate crisis and the spectacular media failure of the Scotsman newspaper in covering the new Cambo oil field. This week they published an article claiming that the new Cambo field will ‘help the UK cut its carbon emissions.’ The reality is that the new oil field alone will produce 10X Scotland’s annual emissions. This is a mainstream newspaper publishing disinformation and comes on the back of political failure of leadership from both the Scottish and UK Government.

You find yourself commuting home from work one day. Unexpectedly, your train stops mid-tunnel. You then notice that water is seeping through the closed doors, rising from your ankles, up to your knees, then your neck. Nearby, someone lifts a child above the water. You stand on the seats struggling to breathe. Some of your fellow passengers will survive, others will not.

We have passed the point at which nightmarish metaphors for climate breakdown, and the lived reality of it, collide. Earlier this week in the Chinese city of Zhengzhou the scenario described above happened, while hospital power systems failed and 200,000 people were evacuated.

LATEST: Stunning footage shows the subway system in the city of Zhengzhou, China, inundated with rushing water.

The death toll from the flooding has risen to at least 25, with seven people missing. https://t.co/gbXDTcbOHy pic.twitter.com/wLnCUtu4wE

— ABC News (@ABC) July 21, 2021

Would you get on that train willingly, knowing the risk?

Unfortunately, despite a diet of despair in the form of wildfires, droughts, rodent plagues, floods, heat bombs and melting permafrost, the question still feels academic.

Taken together, these are no longer harbingers, but rather a new reality. This is what business as usual looks like.

Also this week, in apparently unrelated news, we learned that both the UK and Scottish Governments stand behind the opening of an entirely new oil and gas field West of Shetland. In the year Scotland hosts COP26, decisive action to stop hydrocarbon extraction will still be deferred.

Given that it has been their modus operandi for decades, it shouldn’t be surprising that oil multinationals want us to take a speculative gamble on the planet’s future. What is genuinely remarkable is the willingness of most of our political class to support claims that these companies can be ‘key players’ in the transition from fossil fuel dependency.

The core reasons for this support are fairly obvious, but seldom spoken. Within our politics, it remains taboo to suggest that there are alternatives to market based solutions. Yet, every serious attempt to achieve a just settlement within a post-carbon world must at some point break this taboo.

This creates a bind for political actors who want to support the climate movement, but face constant, daily, reminders that the world’s wealthiest democracies have premised their politics on the mantra that ‘there is no alternative.’

Such a system does not see life and abundance as we do: it sees simply raw materials and ‘externalities,’ knowing only the truth of its own insatiable thirst for more.

Only the abstract forces of capital accumulation would tell us to get on the train and take the risk, because, to take a risk is to be alive. In doing so they want us to awaken the primordial sense that somehow the receipt of random reward will provide us with the illusion of control. Put another way, it wants us to remain addicts: dependent.

In Scotland the impacts of climate chaos may still feel distant. This complacency is fed by the curious fact that the future of the oil and gas sector in Scotland, and the current highly marketized basis for running it, actually transcends the constitutional divide.

It’s all part of a great gamble: as audacious as any scheme in the long history of fossil capital The aim is to maximise ‘economic recovery’ for as long as is feasibly possible, while scaling up technologies like synfuels and carbon capture that could theoretically allow private profit and power to be maintained; once extraction is no longer politically acceptable.

There is very little to differentiate North Sea policy in Edinburgh and London, partly because both sides are broadly content to allow that policy to be dictated to them by industry. As the rest of our manufacturing sector has dwindled, oil has enjoyed an ever more privileged status.

In the context of climate chaos, this leads to increasingly absurd debates around transition.

On Thursday, Deirdre Michie, CEO of trade body Oil and Gas UK penned an article in the Scotsman which claimed that the new Cambo field will ‘help the UK cut its carbon emissions.’ Inevitably, a statement so brazenly misleading requires a raft of PR jargon to ensure deniability, in the unlikely event that the sector is ever held to account.

‘It would be far worse for the environment if domestic oil and gas production fields like Cambo are halted,’ it goes on.

These words build on a collection of cheap conflations and carefully hedged promises. But they amount to the universal cry of the addict: if it is just allowed one more fresh oil field, the industry will certainly clean up its act after that.

The case is premised on the UK sector operating higher environmental standards than many other countries, particularly those in the global south. The term ‘environment’ refers to the North Sea itself rather than the ever more perilous levels of carbon in the atmosphere in general, but the confusion is deliberate. These standards, coupled with the technical challenges that have always been present in Scottish waters makes ‘our’ oil expensive to get at, a factor which almost led to an exodus when the 2014 shale boom led to a downturn from which the North East is still recovering.

Michie offers up the vision of a ‘carbon neutral’ North Sea by 2050, which sounds like a misnomer, because it is. A truly carbon-neutral oil and gas basin would, of course, have ceased to produce oil and gas, or at least operate on a minimalist basis to provide feedstock for limited forms of refining and petrochemical manufacturing that cannot be rapidly phased out.

The trick these companies want to pull off is to confuse the relatively small amount of emissions from the process of getting oil and gas out from under the seabed (through activities such as flaring) with the emissions generated when those resources are burned and consumed.

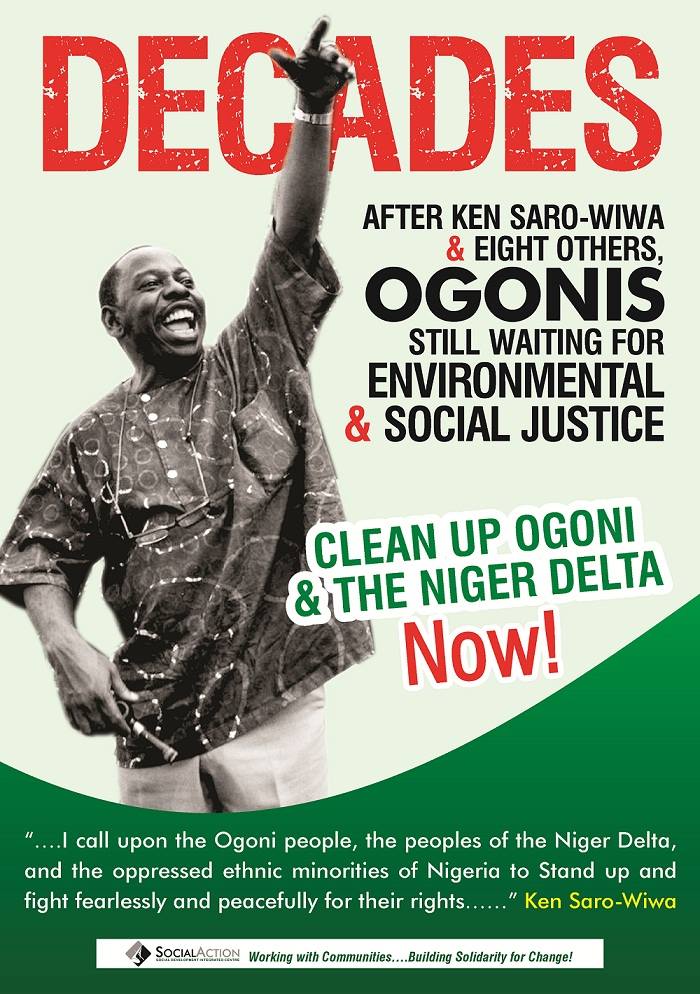

Lurking behind these promises is a darker narrative. The new Cambo field will be 30% owned by Shell, a company not only implicated in enormous environmental degradation, but also found to be complicit in human rights abuses in the Niger Delta.

Closer to home Shell is also appealing a court ruling in the Netherlands that has sought to enforce cuts to the company’s emissions of 45% by 2030: a case premised on the fact that Shell knew about global warming as early as 1986. Are these the organisations that we want to lead Scotland’s transition? Based on their record to date, allowing them to do so is a bit like appointing a tiger as head chef at a vegetarian restaurant.

There is of course truth in that, like any transition process, decarbonisation cannot be instantaneous. Existing resources need to be rationed and stewarded according to key priorities within our society. The profits of oil multinationals, some of whom have consistently shown that they are prepared to make a rush for the exit when those profits slump, should not form part of those calculations.

The truth is that the Scottish and UK Government are more frightened by the alternative to a risky corporate model of transition, than they are of climate chaos itself, because that alternative inevitably involves a greater role for the state and a definition of ‘viability’ that takes account of more than just the bottom line. Thus behind the sector’s claims that ‘we must avoid prematurely draining these key players of their resources …’ there is a thinly veiled threat of capital flight.

The gut response here is to remember the radically different boom times, to keep an eye on the still significant contribution of the wider petrochemicals sector to GPD; to shrug and think that we probably can’t afford to do things differently. We seldom stop to consider whether we can afford the status quo – in 2018/19 Shell stashed £2.7 billion of its profits tax-free in Bermuda and the Bahamas.

While we don’t need oil’s slash and burn execs in the driving seat, we do need the expertise and skill of their workforce, aspects of existing infrastructure, and the diverse supply chains which support extraction. These can all form part of a plan to draw down existing oil and gas reserves over time in the public interest, investing in decommissioning (itself a massive multi-billion pound sector) meeting workforce demands for ‘passports’ into offshore renewables, and deploying emergent carbon capture and storage to meet social need.

What does this form of climate justice look like? Personally, I find the vision offered by a North Sea union leader compelling. He told me of workers who had worked on a specific installation, and wanted to see the thing through ‘cradle to grave,’ with the platform’s construction and decommissioning bookending their working lives.

In the event however, an outfit from Singapore was brought in to decommission the platform, despite the fact that the UK offers a tax break regime in exchange for oil companies bearing the costs of such work.

Given the significance of the industry in the national imagination it may smart to hear that we have run out of time. But it was never Scotland’s oil: it’s Shell’s oil, it’s Marathon’s oil, it’s BP’s oil. Increasingly, it is private equity’s oil, as the post-2014 sector adjusts to an ever more contingent and precarious market.

Some nationalists are fond of the line that ‘Scotland was the only nation that discovered oil and got poorer.’ While the peoples of the Niger Delta would beg to differ, this does at least point to a potentially useful folk memory: the promises of oil were squandered.

Scottish politicians can either use that memory as a resource to build just energy systems, or they can simply continue to stoke a grasping bitterness at not being Norwegian.

Our capitalist societies are built on complex and diffuse webs of promises. This is perhaps one of the reasons why the most eloquent and memorable call for justice of the 20th century spoke of a ‘promissory note,’ – a banker’s draft left at the back of a drawer for centuries, to be cashed long after the elites who signed it off are dead.

Today the perpetrators of climate injustice want us to accept their promises to defer further extraction. The problem is that we don’t have 300 years of struggle to hold them to it, we have ten.

If the Scottish government is backing this Cambo field then they better stand aside and prepare for the Green Party to takeover, I have supported the s n p for years now and I am over eighty yrs old,the future is for the younger generation who deserve a life, they will have my vote and I’m sure there will be Many of my gen who feel the same along with their parents ,the planet Must Come First.

If the world went vegan burning fossil fuels would be a minor problem. Why is more not done to try and bring this about. Let animal rights groups advertise the horrors of factory farming and abattoirs. Remove VAT from vegan foods. Educate.

The only way to avoid climate catastrophy is to build lots of nuclear power stations, and do it soon.

There is no plan B. No amount of windmills and solar panels will be enough.

Its time the environmentalists got real.

Brilliant.