The Barlinnie Special Unit – the less obvious lessons

The Barlinnie Special Unit: Art, Punishment and Innovation edited by Kirstin Anderson. Waterside Press, published 1st October. £25.

A new book explores the lessons learned from the Barlinnie Special Unit (1973 -1994) and what it tells us about contemporary discussions of incarceration, violence, power, class and media.

The Special Unit in HMP Barlinnie in Glasgow operated between 1973 and 1994. It was unique in its day as a therapeutic penal innovation which offered life-changing opportunities to some of Scotland’s – at that time – most violent and notorious male offenders. It is unique today in that it is the only British penal initiative from fifty years ago that anyone in Scotland (or England) cares to remember and celebrate as a neglected success, whose less obvious lessons were never properly learned. Not that everyone, then or now, was positive about it, and the polarised opinions that swirled around this bold experiment in minimising punitiveness behind bars – and finding a role for creative arts in rehabilitation – played a part in both its evolution and eventual demise.

A new edited book seeks to show modern readers what the Unit accomplished, how it was done, why it closed and why it was so controversial. Some of the contributors were personally involved with the Unit from the start, and some in its later years. Others comment on the various issues raised by the Unit, not least “arts in prisons”, which remain vital but are no panacea in the prevailing penal crisis. Some contributions do both. Full disclosure; I have a chapter in the book and was on the editorial group that first set it in motion, but there is much in it that I did not know beforehand, and I commend it to readers on that basis.

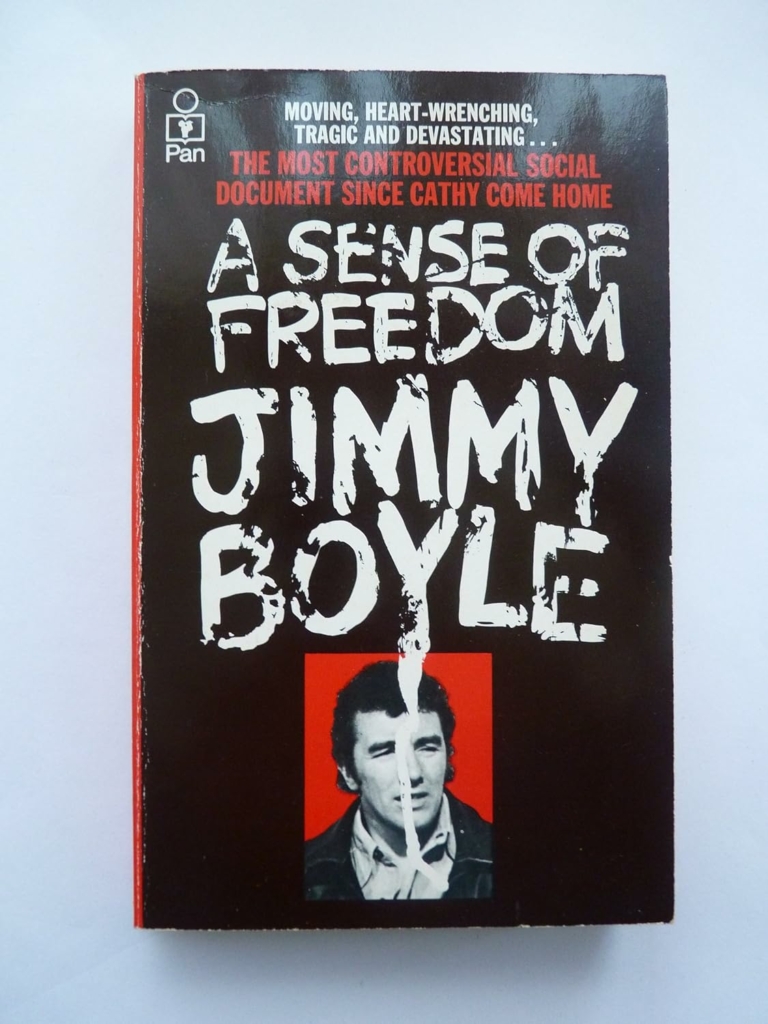

Like many people, I first heard of the Barlinnie Special Unit when Jimmy Boyle’s memoir A Sense of Freedom – whose manuscript was smuggled out of the Unit by the mother of one contributor here – was published by Pan MacMillan in 1977. I was a social worker with young offenders in south London at the time. It was Boyle’s account of growing up in the gangster-culture of post-war Glasgow’s Gorbals, the low expectations his teachers had of “kids like him” and his easy absorption into the juvenile and adult justice systems that first got my attention. I decided that if a man as self-evidently cruel as Boyle had once been – a knife-using enforcer for protection rackets – could become the insightful, articulate man apparent in the book, the work I was doing to divert boys in south London from custody really counted for something. I resolved to become more skilled at this work, and to take greater interest in the policies which stimulated, or impeded, progressive penal change. I knew little in 1977 of the academic criminology that would subsequently engross me, and if I could only pick one book that had a formative influence on the course of my life it would be A Sense of Freedom.

Boyle’s memoir, a display of his artworks in the Battersea Arts Centre and a London performance of The Hard Man, a remarkable play he had co-written with Tom McGrath about the entwined roots of poverty and violence in his earlier life, stimulated my interest in the place where his reform had occurred, the Unit itself. It had been devised by a Scottish Prison Service working party in 1971, whose remit had been to find a response to a small group of prisoners who were unmanageably violent towards staff in the mainstream prison system. Solitary confinement in “the cages” of HMP Inverness had not checked them. Retaliatory assaults on them by prison officers just kept the cycle of savagery going.

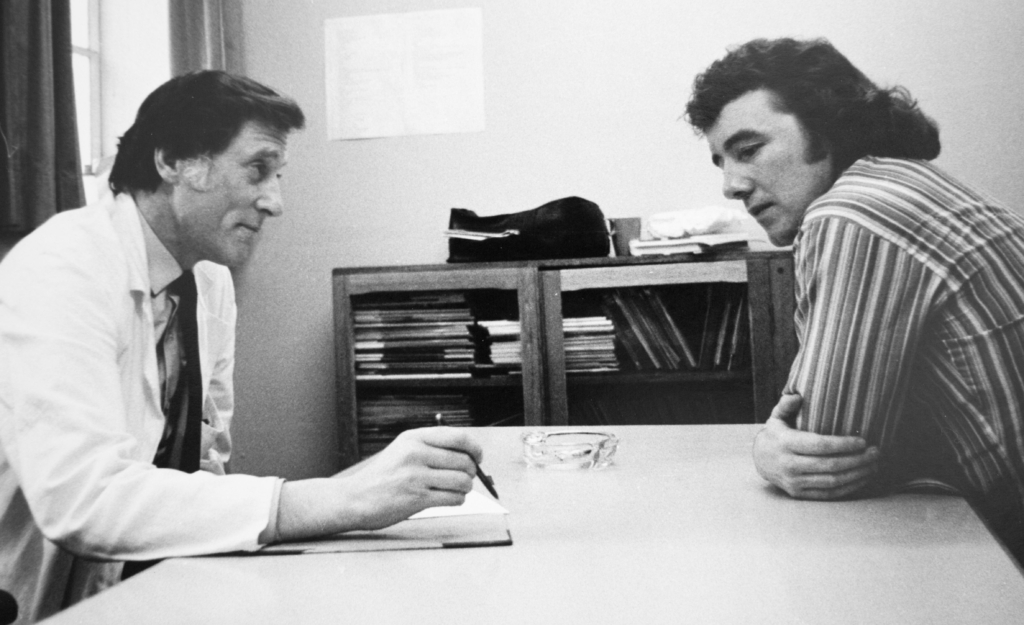

A small therapeutic Special Unit was devised to address this, intending, over time, to render prisoners manageable enough to return to normal regimes. It drew, in part, on practice in the specialist HMP Grendon in England, and Dingleton psychiatric hospital in the Scottish Borders. The Unit’s volunteer staff – officers who wanted to break with the oppressive discipline in the mainstream prison system – had preliminary training in these places. Ken Murray, the Unit’s Chief Officer, was a proud and capable working class man whose common decency towards prisoners was in fact quite uncommon in mainstream prisons at the time. His profound salience to the Unit’s success is registered in the book by a fellow officer who once told me that had he himself not worked in the Unit he would never have gained the insight or the confidence to later become a prison governor himself.

Ken Murray and Jimmy Boyle in the Special Unit © Tony Riley 1975.

The Special Unit was a genuine therapeutic community, daily informed by the acumen of the psychiatrists and psychologists employed in it. A regular weekly meeting took place in which staff and prisoners together discussed issues of living and working in the Unit and resolved often stormy conflicts with talk, initially a new experience for both parties. But the Unit’s otherwise careful planners had not thought how the prisoners would occupy their days. Quite serendipitously, art filled the gap. Boyle ruefully describes in A Sense of Freedom how Joyce Laing (a trained artist and Scotland’s first ever qualified art therapist) started coming in once a week, and encouraged clay modelling. Initially she got zero response from a bunch of men to whom all things artistic could not have been more alien, but after Boyle tentatively gave it a go, and others followed suit, art was what made the Barlinnie Special Unit a legend in penal reform, although it was never all that underpinned it.

Joyce Laing at the exhibition launch of ‘Barlinnie Special Unit — A Way Out of a Dark Time’ in Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, 2017. © CSG CIC Glasgow Museums Collection.

Boyle was the first of many prisoners in the Unit’s first ten years to discover he had a real talent for sculpture and writing. Joyce Laing, unfazed by the company of “Scotland’s most violent men” (as tabloid newspapers called them, contemptuous that they might ever be more than this) helped many of them to flourish. She gave her last interview, published in this book, just before she died in 2022. Taking advantage of the Unit’s open and flexible visiting arrangements, other artists came regularly to the Unit – actors, painters, musicians. These included, perhaps astonishingly, Joseph Beuys (1921-1986), at the time universally acclaimed as Europe’s greatest performance artist, who affirmed the Unit’s ethos, and specifically influenced Boyle. Bill Beech’s chapter explains.

Joseph Beuys and the Poorhouse, 1974. Photo and © Demarco Digital Archive, University of Dundee.

Bill, also one of the editorial group, was himself a young artist-visitor to the new Unit. It has been through knowing him that I have realised how association with it in its earliest years marked so many people, opened their minds to new human possibilities, and gave them a life-mission, even more so than Boyle’s book had given me. The Unit showed beyond argument that some people who had both suffered and done terrible violence could change for the better using tried and tested therapeutic techniques and creative arts. Yet there was relentless political and media pressure, entwined with popular sentiment, to close down a place which looked to some more like an art studio than a proper prison, and indulged violent men instead of punishing them. Scotland’s artistic community, informally led by the inimitable Edinburgh gallery owner Richard Demarco (interviewed here) made a quasi-moral case for keeping it, and arguably helped prolong its life.

But close it did. The Unit in its later years had lost some of its early impetus, and although it continued to take in unmanageable prisoners, and artists continued to work there, over time it was subject to managed decline. Only one later governor, interviewed here by me, tried to revive its therapeutic potential. The academic evaluators commissioned by the Scottish Prison Service (SPS) to review the Unit’s function agreed that it had faded somewhat, but argued strongly that it should be revitalised. The SPS terminated it anyway, to the chagrin of the evaluator who writes here. “So good they closed it down” sighed one Scottish journalist.

Listening to the “lived experience” of offenders and ex-offenders to learn from them what works and what doesn’t to reduce criminality is more common now than it was. During and after his time in the Unit Jimmy Boyle – released in 1982 – was a strong, credible voice in penal reform. Eventually he wanted a break from it: nobody should have to live as an “ex- offender” for the rest of their lives, too often pegged in public only for the worst of what they did, not for the way they changed. In fact, the Special Unit remains unique in still being better known (if it is known at all now) by what some of its residents wrote about it, than by academic or official publications. Jimmy Boyle and Johnny Steele both make contributions here: Hugh Collins died in 2021 before he could write one. Later social-psychological research, described here by the person who undertook it, did validate the regime’s violence-reducing propensities for the majority of men who passed through it.

Sentimentality about the Unit is unwarranted. It did its job well, surpassing expectations, but it also transformed the subsequent penal outlook of many people who saw what it accomplished – before, during and after its existence. Internally, the Scottish Prison Service learned some lessons from it about civility towards prisoners, and a rising generation of younger prison governors resolved never to let the old days return to mainstream prisons. But there were never plans to replicate it.

So what really matters now? Important as the Special Unit was it was never the solution to all the problems facing the Scottish prison system, then or now. Even in its heyday the National Council for Civil Liberties, no less, complained that focussing on the “most violent” deflected attention from the many less serious offenders routinely recycled through ordinary prisons. Lesser measures would have sufficed to restrain and support them, and probably done more to break the cycle of crime. This problem endures. Scotland’s sentencing choices maintain its pole position among Western Europe’s imprisonment rates.

The Special Unit’s story can inform this situation in two ways. Firstly the poverty-to-prison pipeline so evident in the lives of all its residents, and vividly visible in A Sense of Freedom and The Hard Man, remains unplugged. In 2005, a Scottish prison governor surveyed the addresses from which the entire prison population, on one given day, had been sentenced, and found massively disproportionate numbers of them from the poorest areas. Uptodate statistics on this are annually reproduced in SPS reports, but to what effect? Talking up connections between criminality, poverty and inequality, and noting an overreliance on prison at the expense of social justice, are still among the hardest conversations to have in Scotland.

Secondly, the tone of debate stimulated by tabloid newspapers (and now online) still has a dampening effect on rational, evidence-based policy debates about penal issues, just as it did in the Special Unit’s heyday. Tabloids are as likely now as they were then to denigrate success as they are to indict failings. The targets are more diffuse now – from ending short custodial sentences to emergency early release programmes – but there is seemingly no useful, progressive penal reform that cannot be smeared as an expression of “soft touch Scotland”. The politics of penal reform are undeniably complicated and it is a moot point whether the Scottish government is constrained by the punitive constituencies that tabloids purport to represent. But two officially-commissioned reports, in 2007 and 2012, which proposed sensible strategies for reducing prison use, have fallen ignominiously by the wayside, and even insider warnings that we would reach the present numbers crisis were ignored.

The Barlinnie Special Unit shattered many preconceptions about what prisons could be, and about the suppressed talents of the lower class men who routinely caused trouble in them. Granted that it was never a solution to every penal problem, if we had attended more carefully at the time to the insights on class, culture and punishment that the ever-edgy debates about it opened up, might we be in a different place now? Read this book and see what you think.

A fascinating experiment, will there be a TV documentary piece to accompany the book?

The story of the Unit and politics surrounding it along with the cast of fascinating figures who contributed to its success and ultimate demise would surely make a superb subject for a TV drama or feature film.

A documentary made in 1976 is available on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-OQGFFFCSXE

John McVicar also broke free of involvement in crime and became a writer.

I wonder what would happen if the focus of prisons became to try and change the prisoner so they WANTED to go straight and keep straight AND had something like art in order to be able to make it on the outside. They need to be equipped with all they need not to go back into crime eve if they keep contact with their old mates.

I pondered on the possibility that the first sentence or two would focus on “rehabilitation” but reoffending would mean transition to a regime more focused on containment and less pleasant for the offender.

This is a complex area but the impression I get from the article is that the special unit was closed BECAUSE it was more successful than expected.

I heard that it costs more to send someone to prison, per year, than the cost of a top English boarding school.

Why not require all private schools to educate the most “challenging” kids in society, transforming those bastions of elitism into something useful?

Who would pay the fees? The state of course. It would save them a fortune in the long run and result in an army of new recruits to run the country.

Reading about experimental reforms of imprisoned populations, I could hardly avoid thinking about the Vaults in Fallout (4 and the television drama series), nor about the reported changes in how animal testing is done (particularly in social mammals). Whatever the USA was trying to achieve with its conditioning paradigm during the Cold War, the more enlightened thinking seems to be about supporting emergent behaviour with more naturalistic surroundings and what reasonably healthy social environment can be maintained. And if the likes of William Morris is to be credited, this emergent behaviour will express itself in humans in arts and crafts (denial of which may result in poor mental health).

However, we shouldn’t just assume that poverty, class and poor educational experiences are simple gateways to violent behaviour. There are empirical and longitudinal (case) studies to be done here. And there are many practitioners of extreme violence in the upper classes and royalist institutions who don’t get banged up in the likes of Barlinnie. The British upper classes have developed various forms of ‘blooding’ to cultivate tendencies towards extreme violence, which should be compared with similar activities across the population, and within specific subcultures like the military, a disproportionate amount of whom become violent convicts themselves:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blooding_(hunting)

The history of Scotland and its working class is vividly illustrated in this account, which I found highly informative and deeply moving, reflecting as it does the deeply-entrenched problem of widespread poverty and ill-health, whether physical or mental, that is expressed in the Scottish penal system and in the death rates. Both the experiences of these ‘hard men’ and the ‘tabloid’ commentary on this and other initiatives speak to the widespread cultural ‘taboo on tenderness’ that leaves us all hamstrung and silenced in the face of the punitive and bullying carceral tendency of ‘the system’.

We know that inequality is profoundly disabling and disenfranchising. Reference to ‘eradicating child poverty’ just doesn’t cut it. There is a serious work of kindness, care and taking responsibility to be done in Scotland, and it is high time we freed ourselves to set about the task.