Is breá liom Gaeilge (Gàidhlig), but for my own, not yours

McConnell, ‘National News Analyst of the Year’, apparently, was out of the gate early with a headline that rang as true as a Gaelic choir gone flat. ‘I love Irish’, he claims (in Irish, no less, to hammer the point home), but…

Speakers of all three Gaelic languages are so bored of that ‘but.’ It’s the dog-whistle of what-about-ery that raises the question mark over the legitimacy of our languages as contemporary modes of expression, and over our own heads as speakers, but it’s OK, of course, because McConnell precedes his arguments with a slice of the nice guy – he’s our best pal, really. Throughout, he makes hazy reference to the fact that he is likely an Irish speaker, of some ilk or other, himself.

McConnell is, at least, honest in acknowledging that he is not even the originator of most of his recycled arguments, referencing the philosophies of a certain Michael Lewis, from the fount of all critical thought, Vanity Fair – I don’t know who he is, either – who, presumably a monoglot English-speaker with schoolboy French and writing for a lifestyle magazine, is naturally the best source of analysis of the worth of such subjugated languages, in Ireland, or anywhere else.

Seemingly oblivious to the idea that much of the malaise towards native bi- and tri-lingualism in our polities comes from within, McConnell, himself illustrating this phenomenon, assures us that these are “the sort of observations that only an outsider can make.” Lewis’ assertions, via McConnell, aren’t that ground-breaking, really. “As there is no one in Ireland who does not speak English”, therefore, “the vast majority […] do not speak Gaelic,” he asserts, disregarding the efficacy of Irish Language education, in place since the early days of the Republic. A subject which has, similarly, been a feature within certain sectors of the Northern Irish education system for decades, also.

However, Lewis’ analysis of language competence here immediately seeks to double down, reporting, uncited, from his own experience, a prevalent view that if minority-language competence does not match that of majority-language competence, in certain linguistic domains – here, referenced, government – then use of the weaker (or weakened) language should therefore be abandoned. Enforcing this perspective with the surveyed malaise of an indistinguishable cross-section of TDs, their en masse admission of “enough to get by” smacks more of personal disenfranchisement and loss of confidence, a common sentiment amongst minoritised language speakers. Indeed, these representatives’ competence would no doubt be ameliorated by cultivated opportunities to use the language across sectors, instead of boxing it away, out of sight and out of mind in such public fora.

Lewis’ goes on to interpret the Dáil’s bilingual policy as “tokenism”, which, in McConnell’s summation is a “waste of time”. Of course, from the monolingual, or, perhaps, unsupported bilingual perspective, it could be seen as a natural, if not knee-jerk, reaction, given that the world continues to beat to an English-dominant drum and the propaganda, which still sees English promoted as the language of progress and cross-border unity and communication, bellows across continents in the era of post-colonialism.

From the perspective of a native Irish speaker, whose dominant language in many domains, is Irish, or even for a learner, brought to fluency beyond the cúpla focail and trained with the vocab to discuss such contexts, this may not be the case, however. Once again, McConnell’s journalism seeks to other those communities in favour of the needs of the so-called majority, whose needs are, in fact, served adequately by bilingual policy, as it is. Indeed, does a fluent Irish speaker need a TD to repeat themselves in English, when the message was delivered in Irish, anyway?

McConnell next turns his attention to the poor, marginalised English-speaking monoglot, this time embodied by TD Mick Wallace and an episode which can still be viewed on YouTube. McConnell characterises Kenny as the big, bad Irish speaker for expecting the self-professed and linguistically deficient Wallace to avail himself of the freely-provided interpretation system which would have facilitated his understanding. McConnell goes on to admonish Kelly’s “arrogance” in choosing to speak Irish on Lá na Gaeilge (Irish Language Day), indeed, a nationally recognised day set aside to promote Irish language use. Interestingly enough, all parties bar Wallace, in the footage, exhibit a level of spoken competence that it would be mean-spirited to deprecate as “enough to get by”. Indeed, the ease, with which communication flows, demonstrates that Irish could be used far more as a medium of such official communication, would but the personal will of individual TDs were galvanised.

For McConnell, Kenny’s polite request for Wallace respect and facilitate his language choice is warped into “high-handedness” and a “slap-down” and, once again, a speaker of a language recognised as indigenous and official in the citizen’s own country is vilified, simply for causing inconvenience to another who bluntly refuses to avail himself of the opportunities offered to learn a little, if not a lot, and to meet others half way.

Unnecessary and, frankly, incongruent jabs at the linguistic ability of Sinn Féin TD Mary Lou McDonald, and her former leader, notwithstanding, McConnell goes on, statistics to boot, reminding speakers of minoritised languages what they already know: they are a minority community. However, the argument develops, McConnell pleads not to be “burned at the stake”, thus appealing to the good will of an already marginalised strata of society, in pardoning his jocular examination of whether their human right to language should be upheld.

After a brief foray into his own drunken misadventures, whereby linguistic difference from the English-speaking majority and the English, suggests such tokenism – castigated in the mouths of others a few paragraphs previously – is now rendered advantageous, between how own lips. McConnell again plays the faux ami relating his own parental choices, but delivers the regarding his own daughter’s Gaelscoil education:

“We have sent our daughter to a brilliant gaelscoil.”

Now we uncover the root of such omniscience. McConnell will have to excuse me if his sentiments jar, here in Scotland, where I know of parents, in various local authorities, who still face the rejection of their legitimate and legal claim to Gaelic-medium education for their own kids. McConnell’s own admission reeks a little too much of the privilege of choice, no doubt enticed by the informative leaflets extolling the benefit of bilingual education, the like of which here are generously distributed by the likes of Bilingualism Matters, over here.

BilingualKidSpot.com notes that:

Studies show that being bilingual has many cognitive benefits. According to research, speaking a second language can mean that you have a better attention span and can multi-task better than monolinguals. This is because being bilingual means you are constantly switching from one language to the other. Numerous other studies suggest that bilingualism can also reduce the risk of having a stroke.

Good news for iníon Mhic Chonaill. No doubt it is a “a joy to watch her language develop,” but let’s refer back to the headline which explicitly joins voices with the throng, calling for similar opportunities for other children to learn Irish to be, at best, reduced if not eradicated altogether.

McConnell continues to condemn the abilities and efforts of teachers working in Irish Learner Education across the land. Referring their work as a “calamitous failure”, he is seemingly mute when it comes to their constant battle – and that of his own child’s teacher – against the cultural and linguistic tsunami of English-language dominance, coupled with regular derision in the mainstream press. Parents’ evening must be quite the experience.

Let’s look at young McConnell’s opportunities, though, and the Gaelic life-world she now inhabits. Irish kids benefit from a situation where their own Gaelic language is made considerably more visible and appetising, within youth culture, than it is over here. The likes of TG Lurgan have done great work in building a bridge between the teenage preserve of English-language pop culture and a language, which seemingly for the hundreds who’ve gone through their system, has connected the mainstream to their bilingual experience, via a language rooted in their homes and identities. Off the back of the YouTube sensation, TG4 (Ireland’s version of BBC Alba) have sent consecutive Irish-singing entries to the Junior Eurovision Song Contest demonstrating firstly, that the language is neither a barrier to opportunity or success, but indeed a conduit for it and secondly, that the language could and does occupy a place of respect and equality on an international stage. They are creating role-models who are at once exemplary and accessible.

McConnell might consider those children “die hards”, however, or require their parents “to come down from their high perch and accept reality”. Again, it’s the fault of speakers and activists, working voluntarily to maintain the language, that the necessary “reform” has not taken place. This, regardless of what Irish-speaking communities may be doing to shape their own futures, or deem necessary for themselves.

It really is hard to reconcile McConnell’s choice of education for his own with what he, himself, describes as the “colossal waste of time and inconvenience” of others. The article belies little consideration of the experience of native-speaking children in the Gaeltachta and their education needs, or indeed, those of others, moving in or even outwith, who would be better served by benefitting from the opportunity to learn, before deciding, of their own free will, whether it’s not for them.

Then, to balance the point, McConnell makes the cynical choice of selecting the locality where Irish is supposedly spoken least – metropolitan Dublin – selective amnesia preventing the recognition that the capital houses a number of national institutions – including Conradh na Gaeilge and Foras na Gaeilge, but not limited to those primarily language-focussed – who are there to cater to the whole population, including Irish speakers. Dublin’s local Irish-speaking population, with speakers using the language daily, escape a mention, as does the possibility of speakers moving into the capital and with the legitimate legal right to use the language when engaging with the civil service and with the political system in Irish, wherever they were born or currently live, and to see it represented fairly and visually, on signage.

Poor unfortunate tourists come under the spotlight next. Folk who, of course, are totally used to native bilingualism represented in signage and throughout the trappings of nationhood. Folk who might be traumatised by a mythical Irish-only timetable into silence and unable to ask a passer-by for an impromptu, however imperfect, translation. The news, now, is that the 98% of the bus-travelling population who think they don’t use Irish actually do. If they travel daily, they will almost certainly recognise the names of the stops through a process of osmosis and, indeed, hearing and understanding is using.

In summation, McConnell reflects that “the language serves little or no practical purpose in the primary running of the State, except on ceremonial occasions,” negating his own logic, whereby the removal of Irish from the education system, and across the board – which constitute informal language acquisition opportunities – effectively advocates, itself, the marginalisation of a whole generation of young people from a key aspect of the mechanisms of statehood and public life, however “ceremonial” (another by-word for tokenistic).

The final blow comes in the insidious juxtaposition of the removal of history and geography from the national curriculum, a move which was unanimously unpopular, with the maintenance of Irish language education. Thereby setting the two up in opposition to each other, McConnell is effectively intimating, here, that those Irish-speaking children, or those in the process of learning, are somehow scapegoats for ill-advised government policy. But, if every child who has gone through fourteen years of Irish-language education is part of a “niche”, then that niche surely amounts to millions. Unlike McConnell, I’ll not comment on their attention spans or personal attainment in class, regarding this “much ignored […] core subject.”

If, to the general population the Irish language is “ignored”, or, perhaps, goes unnoticed this could also be interpreted as it being so normalised within society that it escapes notice. That non-speakers encounter the language of speakers on the street and pass them by, unphased, uninterested in their private conversations. That they recognise that Irish-language broadcasting is primarily not aimed at them, though accessible through subtitling, and that they are at liberty to change channel, according to their own predilection.

McConnell ends with a rallying cry for choice, which really screams inequal opportunity, failing to consider how such choice might be informed, or even made for others by those who hold the power. How, in any given lesser-used language context, according to reams of research findings, the choice, inevitably, is for the language of globalisation and commercialisation, instead of the other, something rich, unique, more bespoke. Unless awareness of it through education is at the heart of it all, of course.

Yet, despite choosing Irish for his daughter, the self-same language should be “consigned to the marginalised status that it holds”. Calling for your own daughter to be marginalised, by the time she reaches the fluency afforded to her at the Gaelscoil, is quite staggering, but what a devastating, demoralising and undemocratic wish for anyone’s child. To reduce the number of people they may interact with, through the language. To reduce their opportunity to understand their own nation’s history and culture through its own, original language. To tie their tongue when the time comes to articulate all they have learned about the world, as Gaeilge, to put their needs and desires for the future before the people they have voted to represent them.

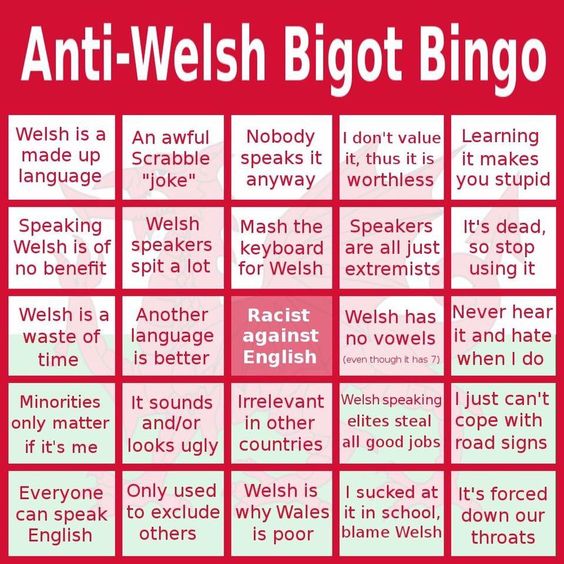

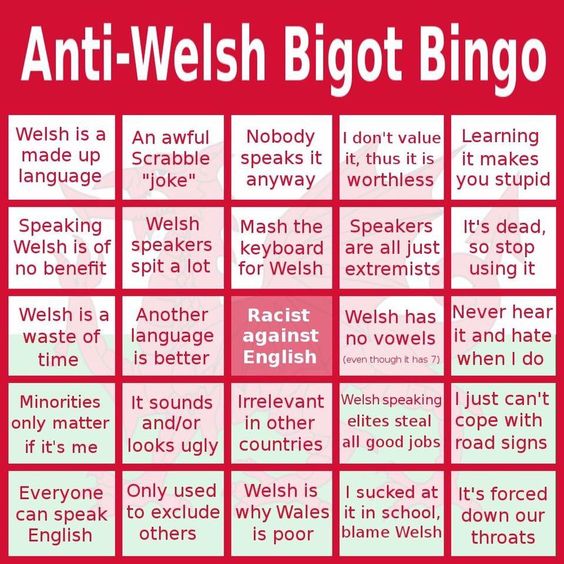

McConnell would do well to recognise, whilst he may not call for it explicitly, that in writing and publishing which interrogate the human right to language and instruction through that language, that he actively foments to an anti-Gaeilge culture, all too visible online. These are sentiments which grow arms and legs on the street, if they are not consigned to the shadows, as is all too clear north of the border.

In Scotland, this is the situation we currently occupy, with a paucity of MPs and MSPs who speak our Gaelic and understand first-hand our needs as a linguistic minority. Less so, those able to use the language within Westminster’s system, echoed with the chagrin, at Holyrood, in using the language to discuss anything other than the language itself. The deficit of qualified teachers able to meet the growing demand for learning in our schools is confounded, amongst some sectors of academia, with the inadequacy of their training, and so the waft of invective sounds familiar in the ear, as it traverses the Straits of Moyle. McConnell’s piece reads particularly ugly, in print, however with the ‘I’m alright, Jack’ attitude of someone who’d snap up opportunity with one hand and snatch it from the hand of others, with the next. Yet again this is the stuff of national press, and across borders we are all familiar with this droning. As we say in Gaelic Scotland, nach paisg e a phìob (would that he’d pack up his pipes), whether said pipe is played by the uillean, is Highland in accent, or otherwise.

*

Alt iontach. Well done on a great piece. McConnell shows he knows little about the purpose of education.

Tá an artagail go maith, go deas agus go ró-cheart! Tá na daoine Seoinín (in aice le Mac Dhómhnaill an t-sgríbhneoir nuachtáin in Éireann) ag ionsaí in aghaidh nó in eadán Gaeilig gach latha, gach seachtain, gach mí ‘gus gach bliadhain, agus is maith liom an sgríbhneoir an t-artagail seo mar chuir siad amach an fór sgéal na Gaedheal trasna nan Gaedhealtachd (Éireann, Albainn, Mhannain, Gailíse, Albainn Nuadh, Oileán Naomh Eoin, Talamh an Éisc, Ontario, Caroilín Thuaidh, Appalachia ‘gus san cuid mhór na h-Astráil fosta).

Tar muid faoin ionsaigh amadáin Seoinín gach t-am agus gach aimsir fosta! Ba mhaith liom do fhéiceail na Gaedheal le chéile ag obair agus ag troid fá choinne an teanga nan Gaedheal trasna nan Gaedhealtachd agus trasna na nDomhain fosta. Ba mhaith liom do fheiceail an gluaisceart nuadh nan Gaedheal ag obair trean nó láidir le haghaidh agus fá choinne cearta sibhialta nan Gaedheal arís! Tá scathan nó grupa h-ollmhór nan Gaedheal taobh amuigh as ceanntar dúchais trasna nan Gaedhealtachd agus b’fheidir tosóidh siad ag obair agus ag troid láidir fá choinne and teangaidh nan Gaedheal fosta. Tá Gaedhealtachd nua trasna na h-Éireann go háirithe anois, i gCluain Dolcáin (BÁC), Loch Riach i nGaillimh, Carn Tobair i nDeisceart Dhoire, ar an t-Inis i gChlár agus san Iarthar Bhéal Feirste fosta.

Tabharfaidh teanga nan Gaedheal ar ais arís trasna nan Gaedheal agus idir muinntir Gaedhealach trasna na nDomhain fosta!

Ba mhaith liom an latha nuair beidh na Gaedheal na h-Albainn, Mhannain, Gailíse ‘gus Éireann (san Eoraip) agus na Gaedheal in Albainn Nuadh, Talamh an Éisc, ar Oileán Naomh Eoin, Ontario, Caroilín Thuaidh agus Appalachia (san Mheiriceá Thuaidh) agus san Astráil istigh san haon stát náisiún nan Gaedheal faoi cosanta na Croí Ró-Naomhtha / Naofa ‘gus an Lámha Dé fosta.

Smaointí deasa: ach ní mó leat staidéar beag eile a dhéanamh ar úsáid an uraithe, agus tú comh bróidiúl seo as an teangaidh. Ádh mór.

It sounds like the definition of choice regarding the NHS from those who can afford BUPA. The choice they seek is one you have to pay for.

Thoroughly enjoyed the article. One minor typo though, the man here refered to as Kelly is Enda Kenny. I had to consult the video for clarification.

Sorry, fixed. I blame the Easter holidays.

I enjoy trying to learn my native toung. I feel Im fixing what CAPITALISM screwed up.

The Irish Examiner posted my response to McConnell today. Whatever about the overall argument he is trying to make, his article was filled with factual inaccuracies. https://www.irishexaminer.com/breakingnews/views/yourview/readers-blog-relevance-cannot-be-the-standard-by-which-we-decide-on-the-future-of-irish-in-our-schools-916296.html?fbclid=IwAR3-3cK-YkMxDrRKVV-21ZWolmyqOLSMDeSWit9bujVKV3bpF0kVpKybTyA

Great response. Maith thú.

Is math a rinn thu a Mharcais…Tha toiseach leabhair ann a seo saoilidh mi.