Exam Time

James McEnaney explores the lockdown’s impact on children and school pupils sitting exams – and what it tells us about the deeper problems in Scottish education.

So, first thing’s first: what exactly is going on with this year’s exams?

Well for a start there aren’t any, not with lockdown rules and social distancing protocols. Of course, pupils in S4-6 still need to be awarded qualifications, so the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) has had to come up with an alternative approach: using teachers’ judgements of their pupils.

After all, teachers know their pupils best – they’ve been working with, observing and assessing them for months, perhaps even years – so it makes sense to ask them to take the lead here. They’ve also been submitting estimates for years, so the systems for that are already in place. The wheel has already been invented – it just needs to be turned, right?

Wrong.

Unfortunately – but unsurprisingly – the SQA has insisted on complicating the process. Estimates are now broken down into many more levels than before and, crucially, all schools and colleges will also have to rank their students. This is to allow for “moderation” of teachers’ estimates, a euphemism for changing pupils’ grades based on the performance of previous students.

It also means that some students will be awarded a fail even after their teacher has judged them to have passed.

Why? That’s easy: to protect the status quo and all of the systems, structures, organisations and reputations that depend upon it.

The SQA wants this year’s stats to look much the same as last year’s, and the year before that, and the year before that – for the typical distribution of Scottish results to be maintained. They want this to be seen as a fair and respectable method for maintaining the credibility and value of qualifications being issued.

They want no questions asked and, judging by Thursday’s education committee session, aren’t up for answering them anyway.

Ultimately, when things calm down, the SQA wants a compliant return to normal.

Well let’s talk about normal.

Normal is an iron-clad link between affluence and attainment. Normal is a qualification system that largely rations success by background, not talent or potential or effort. Normal is schools within a few miles of one another achieving results that are worlds apart. Normal is rich parents and private schools buying success while those with least are left behind.

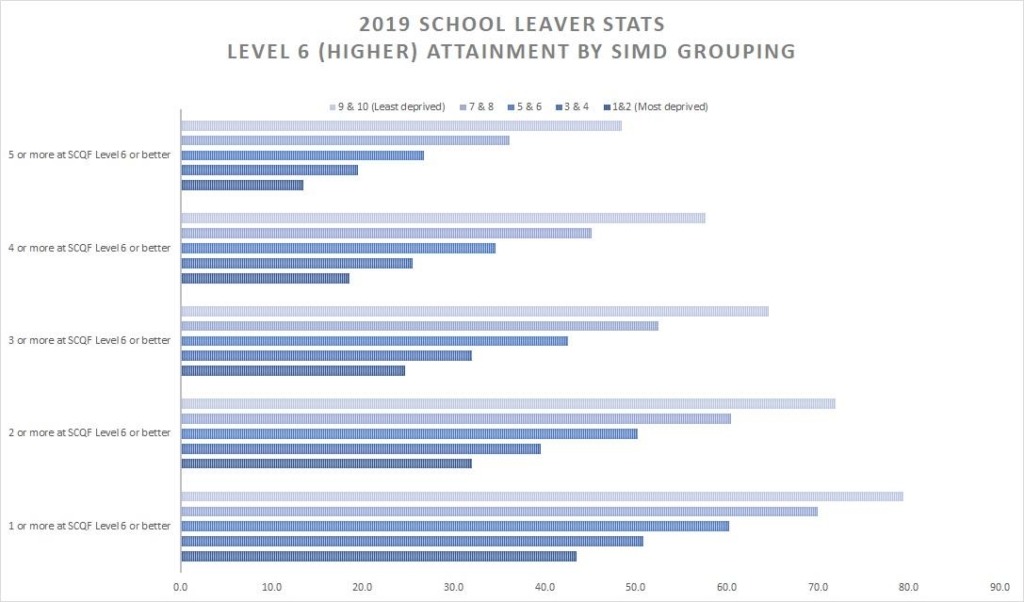

It’s less than a fifth of pupils from those poor areas leaving school with four Highers – the standard university entrance benchmark – while nearly 60% of those from the richest areas manage to do so.

It’s schools in poor areas being unable to even provide as many options as those serving wealthier catchments, a postcode lottery of charges as high as £125 for exam level practical subjects, and a paid-for exam consultancy service dominated by private schools.

It’s a system that ensures that the ‘best’ kids will always get ahead, whether through private schooling, tutoring fees or the simple fact that the whole game is rigged.

Normal is buttressing inequality while we talk about building a better society: rewarding affluence and calling it meritocracy.

Normal is obscene.

Normal is a failure.

And look at us, working so hard to protect a system that treats tens of thousands of young people each year as socio-economic collateral damage; one that has failed so many, for so long, in the name of ‘fairness’.

This was our chance to start to think about – and build – something much, much better; instead we’re going to throw it away because of a toxic mixture of desperation, deference and cowardice.

The problem is priorities, and the SQA’s are wrong.

If we are to deploy system-level data to ensure ‘fairness’ for students, if we really are going to use statistical modelling to right some unbearable wrongs, then we should at least have the guts to do it properly – we should be fighting for students instead of a corrupted status quo.

So if the sacred grade distributions need to be maintained then fine, but why not apply that philosophy across the board? Let’s decide that 30% of Highers awards would still be A grades, but ensure that this applies to 30% of the richest kids and 30% of the poorest and 30% of everyone in between.

We can do the same with all other grades, too, so the data remains consistent – the only difference would be that academic recognition in Scotland would be evenly distributed across society instead of concentrated around affluent postcodes.

These proposals would be no more unfair than our present approach and would tackle educational inequality at a stroke. They would allow exceptional kids from the poorest areas to succeed in place of mediocre ones from wealthy backgrounds.

They would close the attainment gap.

Might some students do better than they would otherwise have done? Absolutely.

The student who works hard all year but spends evenings and weekends caring for their parents might get what they actually deserve. Someone whose school has never had the resources to support their learning difficulty might get an A instead of a C. The talented kid who would be going to bed hungry the night before the exam might pass.

The hand-wringing classes and those running Scottish education would regard this as a disaster; others might call it justice.

But isn’t there a chance that able pupils could lose out through no fault of their own? Won’t some kids be disadvantaged purely because of their circumstances?

Of course – after all, we wouldn’t want to change too much, too fast.

What a pile of pash.

I work in a school in one of Scotland’s poorest areas. None of what the Eructation Spokesperson for RISE Scotland suggest would help anyone.

If the kids we teach can’t write or spell, then they can’t. And saying that 30% of them can won’t solve anything.

The problems are deep seated and routed in generational poverty, as James alludes to. Many of the schools like the one in which I work are very well resourced. Scot Gov’s PEF for example provides a lot. Sure, we could do with more staff to handle our already enviable teacher-pupil ratio, more support staff trained in working with traumatised kids and well… that’s about it, short of one-to-one support for parents who themselves come from families mired in poverty, substance abuse, malnutrition, violence and low aspirations for generations.

The SQA have no power to change this. The ScotGov has limited powers.

I get it that James doesn’t like the current ScotGov. I don’t support all they do but things are better than they were 10 and 20 years ago and a different world from my own schooldays. In short, we have limited powers as a nation so don’t expect us to solve the misery of decades (or longer, if you wish to trace some of the families back to 19th Century Ireland/ Highlands as Alistair McIntosh has alluded to in earlier work). As someone on the chalkface trying to make a difference, James’ tantrums don’t help me one iota. Little wonder RISE sunk in the polls.

Education Spokesperson…

Education is devolved yeah Seonaidh?

So it is… silly me.

As is the poverty we’re talking about. Power devolved is power retained.

But, you know that.

While I have a fair amount of disagreement with Seonaidh, I find myself in greater disagreement with the author. This article is based on ‘straw men’ fallacies.

‘The Scots Gov has limited powers.’

I think you let the Scottish government off too lightly. When the SNP took power in 2007, it went ahead with the ambitious Curriculum for Excellence programme which SLAB had started. I suspect that it gave very little thought to this or to school education in general. The calibre of people in charge of schools includes Fiona Hyslop and Angela Constance; not individuals who inspired confidence. John Swinney’s reputation has not been boosted by four years in charge of Scottish schools.

The previous Labour administration was no better. CfE was their baby and the people they had in charge, including Hugh Henry and Cathy Jamieson, were equally unimpressive. If you have the ‘best small country in the world’ – copyright Jack McConnell – you are unlikely to admit that many of the schools are, for whatever reason, inadequate.

That said, I agree with much of your comment about resources. It is – comparatively – easy to find resources for pupils. Changing a culture which does not much value education is vastly more difficult.

There is a reluctance to accept that such a culture is deeply ingrained in parts of Scotland.

Having powers over management of education but having had little or no management of the nation in which that system is based is like pissing in the wind. I once saw Alistair McIntosh talk of the broken cycle of culture – the indigenous peoples long divorced from their heritage, language and land. IIRC, the context was Mic Maq chief Sulian Stone Eagle visiting Scotland to offer support to the Harris Super Quarry opponents and those in the Pollock Free State protesting against the M77 bypass through a working-class area. It was observed that almost all the names in the slums of Glasgow were either Irish or Scottish Gaelic – the grandchildren and so-on of famine, poverty and clearance. Add to that the wars and economic destruction of the 20th C and in more recent times the Thatcher years.

Mike Small/ Bella may laugh ‘oh but education is devolved’ but how can one semi-powerless administration repair the damage of a century or more? We do indeed have limited powers but even with full-powers, it will take a long time to turn it around.

Yes, resources at my place of work are excellent and we also have an excellent staff/pupil ratio and funding to do a lot of community/ family liaison and support. It’s still not enough though.

I don’t agree re CfE. I generally despise Labour but the CfE was/ is a step in the right direction. It’s a nod to or even an attempt to replicate a more ‘Finnish’ system here. I don’t think our rabid media, councils and even headteachers are ready to let go though.

So, yeah, the SQA can fart about with that 30% – maybe kids who can’t barely say ‘bonjour’ will suddenly become semi-fluent in French, on paper – but it won’t address the real problems.

Sorry, I do not buy into this grand children of ‘famine, poverty and clearance’ view.

Scotland in the 1950s, when I went to school in a Glasgow housing scheme, was clearly leaving behind the long legacy of poverty. It was an optimistic time and – judged by the material improvements around us – this was justified optimism.

Real poverty had largely – and thankfully – been defeated. Today, Scotland is materially far, far more wealthy than in my childhood. There is far more to it than the ‘damage of a century.’

What derailed this success was the collapse of the industrial economy.

A large chunk of Scotland has never been successfully integrated into post-industrial Scotland; i e the society we have had for the last 40 years. One reason for this is that the political establishment (SLAB and SNP) have failed to acknowledge the existence of the ‘left behind’. Paradoxically, our politicians are, and have been, too upbeat.

I don’t think that we can copy Finland. It does not have our social structure and deep rooted problems. When Allan Little of the BBC made an excellent documentary about Scandinavia, ‘Our Friends in the North’, he asked the Finnish Minister of Education explicitly; Could Scotland copy Finland ? The answer was – No. The Finnish system depended on the under pinning of Finnish culture.

Good point about grades being given to fit a rigid pattern that is itself a source of inequality. Danny Dorling explores the bell curve idea further: http://www.dannydorling.org/wp-content/files/dannydorling_publication_id5844.pdf

That we have an unequal education system has been known for generations. We have been able to quantify it in terms of exam results since Michael Forsyth forced the publication of exam results in the early 1990s.

(The Herald today produces figures for Higher passes. In Boroughmuir Secondary 72% of pupils get 5 Highers. In WHEC (Wester Hailes Education Centre) 0% do so.

Both are state comprehensives in the same local authority. They are a couple of miles apart.)

Why has nothing (successful) been done to change this ? At its simplest, we as a society do not care enough. The system works well for a huge number of (mainly middle class) parents and their children.

With regard to the ‘sacred grade distribution’; teachers in the 1980s – when ‘O Grades’ were being replaced by Standard Grades, were told that this was ending.

‘Norm referenced’ assessment (with 10% getting an A; 20% getting a B etc) would be replaced by ‘Criterion referenced’ assessment (pupils would be assessed on what they achieved. The comparison made was with the Driving Test, where you are assessed on the ability to achieve specific outcomes such as an emergency stop.)

Like so many ambitious educational reforms, it was vastly time consuming and changed little.

Unlike, James McEnaney, I would not trust teacher assessment. There is a solid reason why we have had external exams for so long. All it needs is the suspicion that teachers are ‘fiddling’ the system for others to conclude they must – to protect their pupils – do the same.

Making the outcomes of the school system more equal would require a massive investment of time, effort and money. It would also involve more testing – to ensure that the changes were working. There has never been the commitment needed to achieve this.

In the coming years, the Holyrood government is likely to be too busy firefighting the economic consequences of the C 19 virus to even attempt this. The last chance was the one John Swinney had and, sadly, it was not taken.

Regarding Florian’s point about Boroughmuir and WHEC, the latter is further disadvantaged by a combination of its roll (being one of Edinburgh’s smallest) and the statistical methods employed. Higher results are not counted singly, but in blocks. Thus schools where tiny numbers take Highers may register ‘zero’ success.

I know this because the sole pupil who sat Higher English at Craigroyston High School in 2004/5 got an A. In other words, 100% of our participating pupils that session got the top mark possible. A great result for pupil (and staff), which was not acknowledged in the published ‘results’.

The Scottish Government has invested hundreds of millions of pounds to help those from a disadvantaged background and close the attainment gap.

They have had quite a measure of success. See me post below.

It should also be noted that 95% or more of school leavers go on to a positive destination – HE, FE, apprenticeship or job.

I agree, Legerwood.

The extension of the number of bands for Council Tax has raised additional revenue which has been hypothecated entirely for education and goes directly to schools and not via Councils. Early data indicate that it is, indeed, having success. This hypothecation will have to be continued for a number of years and, in my view, should be increasingly directed to pre-school and primary schools.

Educational change takes time and, as Wul and Mr Chips have indicated, below, there are inequality issues within society that also have to be addressed. Once Covid-19 is over, we really need to look at the inequality issues in Scotland and who really ARE key workers. What we do NOT need is more austerity.

Every system needs its checks and balances (my preference right now would be for teacher predicted grades and sample moderation of these to ensure accuracy and accountability). To ask teachers to rank their pupils in order of ability lifts the lid on the pretence that our education system is not a competition where you are compared to others. So much for every child reaching their potential – it’s only possible within the range of what’s been pre-established as the norm.

perhaps education is too important to be left to teachers. discuss.

In 2018 UCAS analysed all of the University application covering the period from 2006 to 2018. In order to be able to compare the applications from each of the 4 parts of the UK they applied the POLAR 3 definition of deprivation.

The results for Scotland when comparing the ratio of applications from the most advantaged areas to applications from the most disadvantaged areas they found that in:

2006 the ratio was 4.5:1 by 2018 the ratio was 2.6:1 and the gap had closed purely because of the increase in applications from pupils in the most disadvantaged areas.

In 2019 the gap narrowed again. Bear in mind that at least one third of university/college applications do not go via UCAS. Bear in mind too that students fro disadvantaged backgrounds may go to FE College, do HNC then HND and transfer directly into 2nd or 3rd year of University.

And yet;

The Herald – on 20 March 2019 – reported that there was a smaller improvement in exam attainment among deprived pupils than among others.

Put simply, the attainment gap was growing.

The figures reported in the Herald yesterday suggest that what commentators of the right (Alex Massie) and left (Gerry Hassan) call ‘educational apartheid’ remains very much intact and that – so far – the Scottish Government’s self declared defining mission is unaccomplished.

I don’t buy this notion of inequality within our education system creating the huge attainment gap between richer & poorer areas. The inequality in school attainment is an outcome of the inequality in our society, in my view.

My children went to a secondary school with very high attainment levels. The quality of teachers & teaching was sub standard and many were duffers keeping out the way of the buses. They wouldn’t have lasted a week in the schools in Glasgow’s east end where I once worked. The young people got good grades because of their family backgrounds and thousands of pounds spent on private tuition. Parents round here are rabid about school attainment.

How can you trust a teacher to award a grade when their own ability and the schools’ reputation on league tables is hinged on exam pass rates?

I think that perhaps we need to be more radical and look outside the box of “what we have always done” in Scotland or elsewhere in the UK.

If you are trying to solve a problem a good idea is to look at the start.

Our youngest children begin Primary Education aged around 4 years and 6 months. The reasons for this are historical, mainly concerned with work practices and are not educational. Many countries with excellent and more child friendly systems, such as the Scandinavian countries, do not begin formal Primary Education until the age of 7. Before this, many forms of early nursery type education can be accessed culminating in one compulsory pre-school kindergarten year before Primary One.

A delayed start means many things. In a setting with a better staffing ratio the children can achieve much better developed language skills and concentration. Their natural curiosity and love of exploration can be encouraged through outdoor and physical play. They can be helped and encouraged to relate well to each other, gaining in confidence, trust and respect, which will serve as a good foundation for their mental health throughout life.

None of this is cheap. Countries such as Finland use highly trained professionals. Here we are struggling to expand Nursery hours but councils are tempted to cut back the use of teachers in a setting because of cost. Starting formal education early does not give an early start to excellence. We fudge our description of what happens by saying that the children are mainly learning through play but there is pressure on children teachers and schools to measure up to an expected standard.

The youngest and poorest children start to fail almost as soon as they enter school. Yes of course many children do succeed but could they do better? Teachers and other Education professionals work extremely hard within the boundaries of our present system but is it good enough?

Do you think that there are fewer highly educated people in Scandinavia than here in Britain?

Politicians of any party regard this topic as a “hot potato”. Too many people do not understand the benefits. Yet another major change might lose votes and so we continue to fudge. The Curriculum itself is a side issue. There are many things to learn and many ways of learning them.

Little independent Estonia has just begun to model its Education system on that of its neighbour Finland.

Come on Scotland; we could do better!