The Chrysalis of Hope, a Lockdown Reverie

Somebody tells me it’s day 62 of lockdown. I have come to terms with my mane, my mullet and my curly locks. I have reached the outer limits of my culinary skills and my house is tired of me. I’ve been trying to clean and sort and hoover and do admin that I have been procrastinating over for months, all of which I see now as a sort of displacement activity, rather than my aspiring Marie Kondo moment of zen serenity.

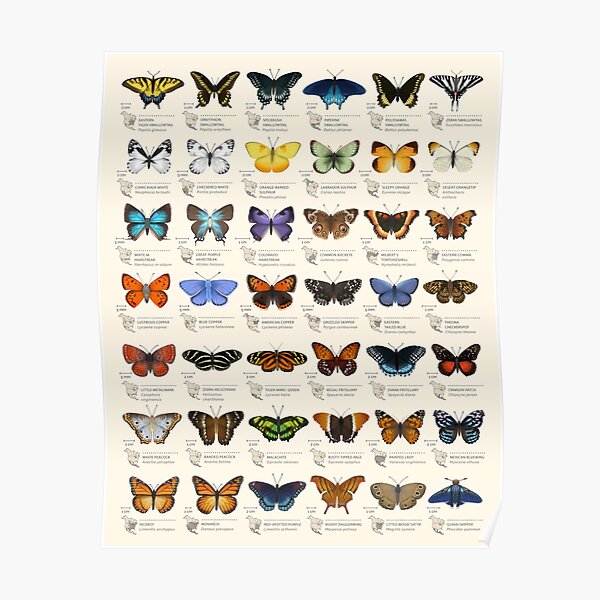

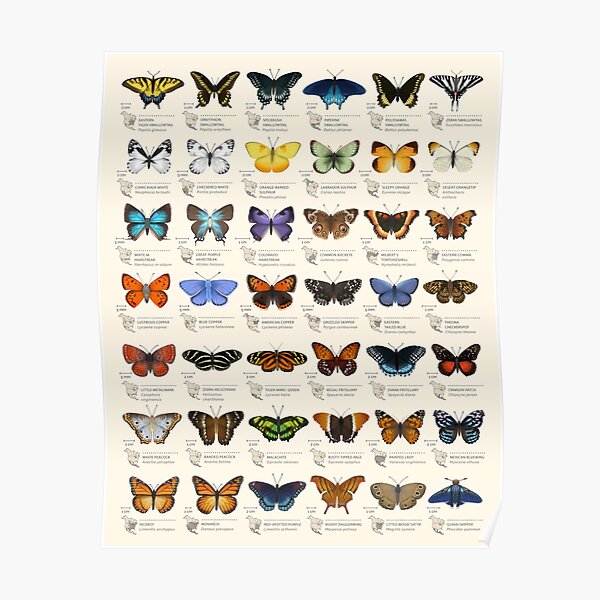

I have spent most of the time dreaming, in a sort of chrysalis of hope, but as we’re about to crawl out of the lockdown that hope is evaporating. I worry I’ll emerge a moth not a butterfly. We think of dreaming as an individual act but it’s a collective one and the corrosive effect of prolonged isolation is beginning to have an impact.

The opportunities for learning and reflection out of the covid experience are overwhelming. The forced inactivity, the moment to think, if even through foggy, fuzzy heads is one that we shouldn’t relinquish. In my late-stage, hairy and confused state, here’s the things I want to preserve from lockdown.

Believe me, and I mean believe me, I am not romanticising the experience of attempting to work from home and parent, never mind work from home and actually ‘educate’. The awe and respect which I previously held for teachers has increased through this experience, but so too has my respect for those people who home-school. The extended period of time off school (six months between March and August) must surely force us to re-think what we are doing here. If we are re-thinking the economy we need to re-think education too. As we’ve been involved in instant home education, the lessons many people have learned are that learning through play, and the importance of nurturing mental health are vital to children and young people and they are not being given proper attention in our current educational institutions. We encourage uniformity, obedience and test people at all the wrong ages. We send kids too early and we keep them indoors too long. We stifle their imaginations and we train them to be good workers.

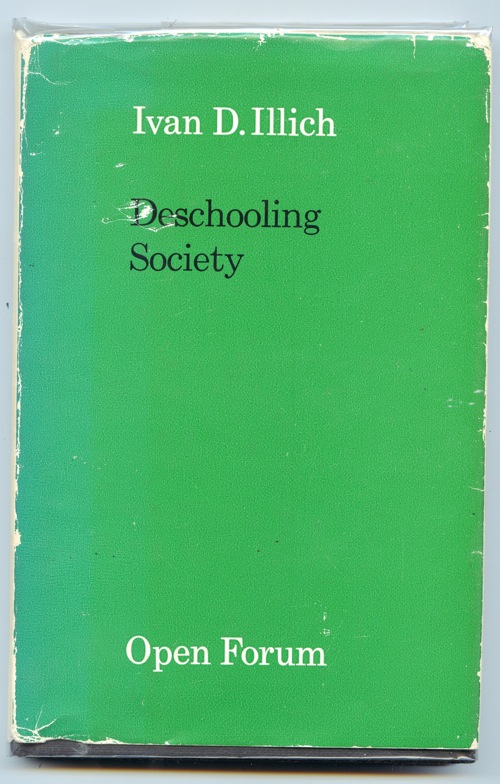

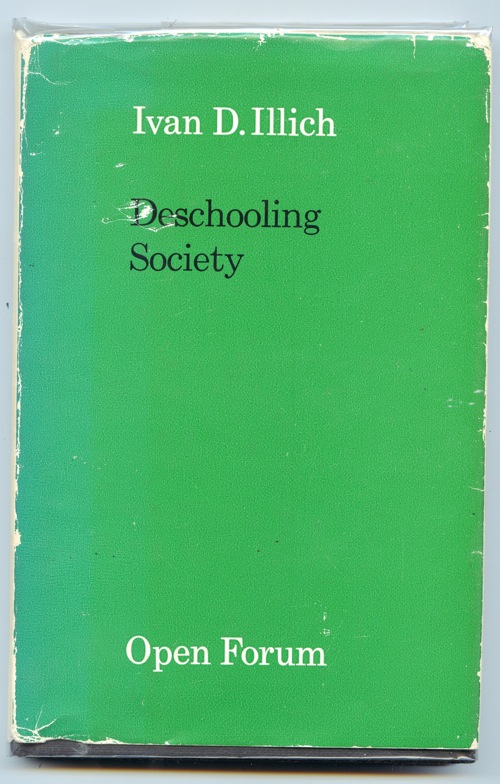

As Ivan Illich wrote in 1973:

Many students, especially those who are poor, intuitively know what the schools do for them. They school them to confuse process and substance. Once these become blurred, a new logic is assumed: the more treatment there is, the better are the results; or, escalation leads to success. The pupil is thereby “schooled” to confuse teaching with learning, grade advancement with education, a diploma with competence, and fluency with the ability to say something new. His imagination is “schooled” to accept service in place of value. Medical treatment is mistaken for health care, social work for the improvement of community life, police protection for safety, military poise for national security, the rat race for productive work. Health, learning, dignity, independence, and creative endeavour are defined as little more than the performance of the institutions which claim to serve these ends, and their improvement is made to depend on allocating more resources to the management of hospitals, schools, and other agencies in question.

– Ivan Illich Deschooling Society

The argument is simple: “Scotland’s children are Scotland’s future. To realise their full potential, they need the very best start to their education. The western countries with the best records in education don’t start formal schooling till children are seven. Instead they have a kindergarten stage based on well-established principles of child development.

Current Scottish policy supports a developmental approach, but the structure of our schooling system makes it difficult to deliver. A statutory kindergarten stage ensures that the ethos of education for the under-sevens is different from that of formal schooling.

In today’s fast-moving, high-pressure world, children need more opportunities to learn through play (especially outdoors), to develop their spoken language and social skills, and to build sound foundations for academic achievement.”

We should add to that, that the best place to learn is outside, that is the origins of kindergarten and having been locked up for so long we should now institutionalise outdoor education from childhood to adulthood.

Those of us who advocate independence should also be advocating independence of mind and drawing on the rich and radical Scottish traditions of generalism.

Second, and allied to this radical re-shaping of education must be some radical re-thinking of work. If some variant of Universal Basic Income is an idea whose time has come, so too is the four day week. The think-tank Autonomy’s report The Shorter Working Week a Radical and Pragmatic Proposal noted: the worrying trends of job polarisation, the explosion of precarious forms of work, gendered inequalities, stagnating productivity growth, the threat (and promise) of automation and the substantial inequality that exists in our society.

They made the case that “the shorter working week is a powerful and practical response to some of these trends. Importantly, it should be understood that the transition towards a shorter working week is possible now and is not an abstract utopia.”

Katja Kipping, co-leader of the Left Party (Die Linke) in Germany which advocates such changes has said: “Increasing social inequality and precarity, gender inequality, the

climate crisis and the finite availability of natural resources call for a radical shift away from the paradigm of expansive production. One political approach is the radical reduction of wage labour while at the same improving social security and providing enough for all. On this path towards socio-ecological transformation, the reduction of weekly working hours together with other forms of reducing wage labour and increasing individual time sovereignty is an important step. For this and for the necessary redistribution of wealth from top to bottom, the progress in production achieved through automation and digitization could be used as a lever. The issue of gender equality and the double burden of women is key here. Shorter work hours are not only healthier for everyone, they also allow for a fair distribution of unpaid work between men and women.”

The New Economics Foundation came to the same conclusions.

Their 2010 publication “21 Hours” argued that a ‘normal’ working week of 21 hours could help to address a range of urgent, interlinked problems. These include overwork, unemployment, over-consumption, high carbon emissions, low well-being, entrenched inequalities, and the lack of time to live sustainably, to care for each other, and simply to enjoy life.

The authors Andrew Simms, Anna Coote and Jane Franklin argued:

“A much shorter working week would change the tempo of our lives, reshape habits and conventions, and profoundly alter the dominant cultures of western society. Arguments for a 21-hour week fall into three categories, reflecting three interdependent ‘economies’, or sources of wealth, derived from the natural resources of the planet, from human resources, assets and relationships, inherent in everyone’s everyday lives, and from markets. Our arguments are based on the premise that we must recognise and value all three economies and make sure they work together for sustainable social justice.”

These shifts, in education, in economy and in how we understand work need to be intentional and strategic, not something we stumble into because we can’t return to the mania of a growth economy without becoming diseased.

All of these things will have to be fought for and articulated, all the signs are that our own leaders are unlikely to have the insight to do this on our own.

If you have enjoyed driving less, cycling and running more, if you have enjoyed cleaner air and the prospect of sustaining a massive reduction in C02 emissions (a new study in Nature Climate Change by scientists from the University of East Anglia and Stanford has found that daily global CO₂ emissions in early April 2020 were down 17% compared to the mean level of emissions in 2019) you will have to fight for it.

If all this seems unlikely, and anger and grief are a potent mix for boosting residual cynicism, one thing might make achieving real change possible.

All of the the lockdown experience points to heightened levels of appreciation. We are appreciating ‘frontline workers’ (previously designated low-skilled), we are appreciating the idea of a nationalised health service, we are appreciating workers from abroad and how crucial they are to our economy and to our society. We’re appreciating nature and the need to be outdoors. We must hold onto these things because bouncing back to the old economy will have them all destroyed.

Cities designed for people, a meaningful work-life balance, a richer education for our children, an economy that doesn’t destroy the environment – all these things are manifest, all these things are happening now, all these things are possible, but only if we emerge as butterflies not moths drawn to the flickering flame of mindless consumption and relentless production.

Great to see Illich being discussed, but I have to argue with your (single) use of the term “home-school”, which home educators in Scotland have long fought to have dismissed as a term for what we do. At the very least, it has no place in Scottish education law and policy, which always uses the term “elective home education” or “home education” for short.

Worse, though, it is a term that has driven misunderstanding of home education practice, and been used to justify prejudice against our community. You can also see it in non-verbal ways – almost exclusively, press reports of home education are accompanied by photos of children sat at the kitchen table, parents hovering over them as they complete worksheets.

Very few home educators in Scotland practice that sort of home education. For the vast majority of us, we home educate in order to free our children from the patterns and practices of schooling pedagogy. The law and statutory guidance explicitly accepts pedagogical diversity, making it clear that teaching, curriculums, and schoolwork are not necessary criteria for assessing education provision. But when you construct what we do as “schooling”, LA education officers – most of whom are appointed without any training in or experience of home education – feel justified in demanding to see copies of work or expecting children to be benchmarked against the CfE – for which they have no legal powers. Worse, it constructs a model that members of the public then measure our individual practice against. I’ve been asked, aggressively, “what, you don’t make them do schoolwork? How irresponsible”.

No, I don’t. My children learn what they want to, when they want to, how they want to, and where they want to. They are bright, inquisitive, and self-motivated – everything that schooling beats out of children.

It’s important to recognise all of that – to recognise the pedagogical diversity and innovation that is commonplace in home education circles in Scotland, because it fits in with the sort of education that you propose. I worry, greatly, that this lockdown is going to make things harder, not easier, for home educators and for pedagogical innovation.

It’s also very important to recognise that what parents are doing now is *not* what we home educators recognise as home education. I’ve had a few people say to me, “I suppose nothing’s changed for you”. Well, it has, massively. We’ve lost our regular home ed group social meet-ups. We’ve lost our art and craft groups. We’ve lost our sports groups. We’ve lost our board games groups. We’ve lost our forest education groups. We’ve lost access to libraries and museums and heritage sites – where much of our “home” education actually takes place. What worries me is that parents, carers, and educationalists struggling to deliver schooling methods at home under lockdown will assume that those difficulties characterise home education, when they don’t. You aren’t home educating, so please do not judge what we do according to what you are experiencing.

Before the lockdown, the Scottish Government was in the process of drafting an updated statutory national guidance. We know from FoI requests that LAs are seeking more powers to control and limit home education, to stamp down on innovation and diversity. It’s bad enough that as things stand LAs can insist that parents and carers follow the national guidance to the letter but that no-one can or does insist that LAs follow the national guidance – indeed, not one LA follows the guidance to the letter, with some openly stating that they do not have to do anything that the government tells them they should do – but some LAs are seeking greater powers to impose their methods on home educators. If new modes of learning and alternative approaches are to become part of the “new norm”, these attacks on our community have to be resisted. The solidarity of non-home educators who care about creating a new society and new Scotland would be appreciated in that fight.

Thanks Mark, all good points taken on board.

You say “It’s also very important to recognise that what parents are doing now is *not* what we home educators recognise as home education.” Yes I understand this but I think people have had a glimpse into the possibilities of changing education and a chance to re-evaluate their work and careers.

I do think that’s true in some ways. We have had a spike in applications to join the main home ed groups, almost all from parents saying something along the lines of, “my child’s mental health has improved hugely since they’ve been out of school”. One parent said to me, “I just thought my son’s tantrums at home were because of us, because his teachers said he never had tantrums at school and never shouted or caused trouble. But now I realise school was so stressful for him, he was bottling it up and releasing it at us when he got home. He’s not shouted at us at all since the school closed”. That focus on a child’s health and happiness, rather than on schooling, is to be welcomed – again, it’s a reason that we know many home educators choose to home educate – because they recognised how it supports the whole child, not just their training for the workplace.

That is very common in the ASN community, which I am part of. I home-educate my disabled son (and daughter) but I speak to others often about what school stress does to children who cannot really cope with it — this bottling up and letting it out at home is normal. And upsetting for families. It gives a false picture to the school too, if pupils are masking just to get through the day. This is sometimes a reason why families opt to educate ASN children out of a school setting.

Mark

The media immediately seized on the term “home schooling” despite the fact that no parent was ever asked to deliver such a thing during the lockdown.

Readers interested in home educators’ experiences with education authorities and other services can read this report, based on extensive surveying of Scottish home educators.

http://www.home-education.biz/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/200310-HOME-TRUTHS-FULL-RESEARCH-REPORT-converted-2.pdf

Thanks

In this context, it’s also worth name-checking Ivan Illich’s ‘The Right to Useful Unemployment’ (1978), which, by chance, I’m currently re-reading, having found it during a lockdown rummage.

“The Age of Professions will be remembered as the time when politics withered, when voters guided by professors entrusted to technocrats the power to legislate needs, the authority to decide who needs what, and a monopoly over the means by which these needs shall be met. “

Thanks MIke, you are on the button and articulating it for many of us.

Really excellent piece.

‘All of the the lockdown experience points to heightened levels of appreciation. We are appreciating ‘frontline workers’ (previously designated low-skilled), we are appreciating the idea of a nationalised health service, we are appreciating workers from abroad and how crucial they are to our economy and to our society. We’re appreciating nature and the need to be outdoors. We must hold onto these things because bouncing back to the old economy will have them all destroyed.’

This is so true and I’d add appreciation of the value and importance of the arts – music, drama, literature and the rest. Never in my lifetime has the phrase ‘man cannot live by bread alone’ been so obviously played out for so many of us.

The other thing I have noticed a lot is the loss of seemingly not that important things that in fact turn out to be so: the meandering, trivial conversation about nothing much in the pub after a day’s slog, the bus to work in the morning, sitting in relative silence but with others doing the same; the chat moaning about the bosses in the corridor… we are such deeply social animals, we can’t cope well without it, it is in our DNA.

And virtual forms of communication and interaction have been proven not to cut it – they serve practical purposes yes, but leave you drained and frustrated that you cannot actually be with those people in person. People say where would we be without them at the moment and this is true but only because we are already used to that way of life. I worry a bit about the idea that education should rely more and more on ‘tech’, something this lockdown has forced me into. I teach at HE level and have done so for 20 years and there is zero doubt in my mind that despite all the advances in mobile communications, what most students value most highly is being in a room with others, learning directly from each other and lead by an expert guiding hand. There is an assumption among older educators who predate the internet etc that we must engage young people on ‘their level’ as digital natives using all the latest digital tools – virtually every educators’ forum / conference I have been to for at least 10 years is dominated by looking at new ‘tools’ for this at the detriment of any discussion about actual educational method. It reminds me of hi-fi obsessives or tech-obsessed composers and producers, who forget about the actual music and spend all their time exploring the latest gadgets instead, forgetting they are tools not an end in themselves. The irony is students don’t give much of shit about online learning tools – they are useful obviously, essential even but are normal, nothing special. What is special to them, as it always has been but is now seen almost as novel, is the idea sparked in the classroom and that only occurs when the subtle interactions alluded to above (in the pub and on the bus), happen when people of physically together. This lockdown has made this even more apparent to me.

“We should add to that, that the best place to learn is outside, that is the origins of kindergarten and having been locked up for so long we should now institutionalise outdoor education from childhood to adulthood.”

Spot-On. Every parent of small children instinctively knows this; the huge sigh of relief as you get the wee ones out of doors and the pressure built up indoors just lifts away.

Being stuck immobile behind a desk, under artificial lighting, for hours and days and years on end is torture for many children.

For sure. This article about ‘forest schools’ is bang on relevant:

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/may/09/i-feel-ive-come-home-can-forest-schools-help-heal-refugee-children

Cheers. Interesting article.