The Importance of Financing Political Movements

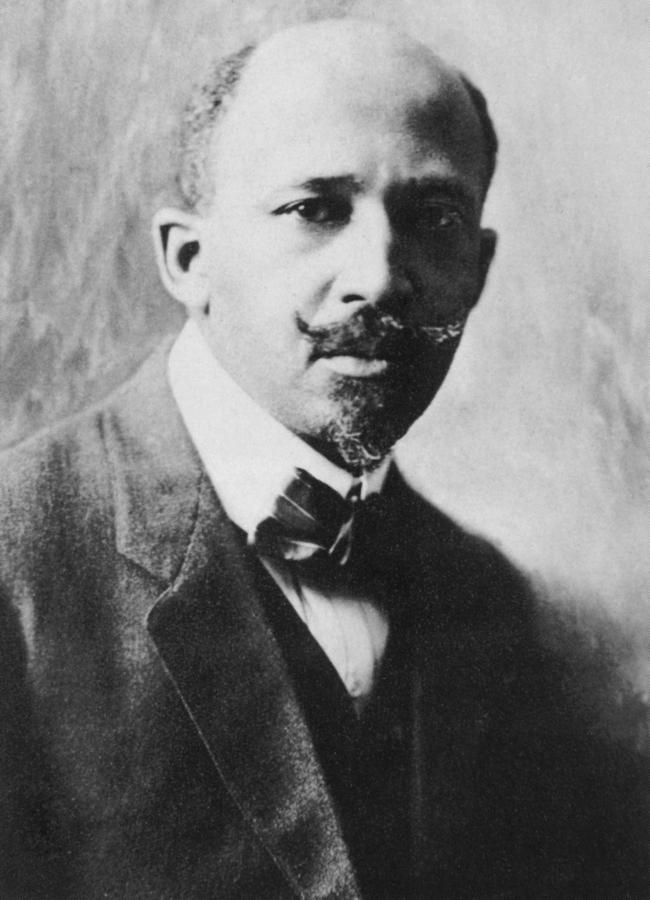

W. E. B. DuBois

Miles Greenwood on the important role of black-owned capital in political movements.

The murder of George Floyd at the hands of the police sparked an outpouring of grief, anger and dejection that, for many people in the Black community, will feel all too familiar. After all, we’ve been here before far too many times. We’ve seen the hashtags before, we’ve been at the demonstrations, we’ve felt the pain. For many, there might be a sense of hopelessness despite the widespread awareness and dialogue, and I get this. Very few of the major protests of my lifetime have amounted to much change.

However, for me, this time feels different for many reasons. For one, Black people on both sides of the Atlantic seem to be organising in new ways that will outlive the hashtags, and the attention of the news cameras and front pages. A range of initiatives have been launched and supported; fundraisers are frequently being set up and Black businesses and individual entrepreneurs mobilising to support their community.

Whether we like it or not, money is an important part of political movements; or as Black Panther Party member Jimmy Skater said, “in order to keep the movement going, you’ve got to have capital.” The Black Panther Party understood that their movement needed strong financial backing, which is why they invested in publishing, commerce and property. And theirs is not the only historic precedent.

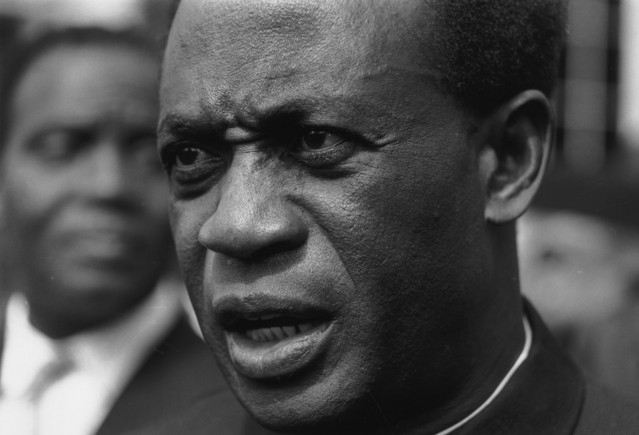

In 1945, delegates from across the African diaspora descended on Manchester for the Fifth Pan-African Congress. The likes of Kwame Nkrumah (pictured above), Jomo Kenyatta and W. E. B. DuBois came together to demand independence for African and Caribbean countries, as well as condemning imperialism, racial discrimination and capitalism. Several attendees went on to play instrumental roles in leading their respective countries to independence. This event, which was so important in contributing towards the subsequent decolonisation of the British Empire, wouldn’t have been possible without the capital of Ras Makonnen.

Ras Makonnen was an activist, Pan-Africanist, political thinker, and he was also an entrepreneur. He owned several properties and restaurants around Manchester, and with the income of his businesses, he was able to finance the Fifth Pan-African congress. We often take for granted that such landmark events require money to organise. Imagining instead that they are a product of the sweat and determination of activists alone. Makonnen’s role, and the people who take on similar responsibilities in financing political struggles, are often forgotten by history. Perhaps its because of an unease we have with private capital playing a role in political and social movements. However, for Ras Makonnen, his private capital wasn’t in conflict with his socialism. In fact, he was one of the strongest advocates of ‘Pan-African socialism’ at the Congress.

Those who are using their businesses, wealth and entrepreneurialism to support the Black Lives Matter movement all over the world, are part of a long tradition of Black-owned businesses and Black entrepreneurs supporting political and social struggles.

Even in Scotland, where only approximately 1% of the population are Black, communities are beginning to organise in ways beyond protests. One of the individuals recently spearheading the anti-racist movement in Scotland is Barrington Reeves. Reeves is the founder and Creative Director of design agency Too Gallus, and he played a prominent role in organising the Black Lives Matter demonstration in Glasgow. The demonstration itself was a great success, with thousands of people turning out to Glasgow Green to peacefully protest and show solidarity.

The anti-racist struggle in Scotland might be aided by more Black-owned capital, but only 3% of small businesses in Scotland are owned or led by ethnic minorities. Reeves said in an interview with the Herald that ‘there’s a real lack of funding and lack of support for minority-owned businesses here (in Scotland).’ And so, in the wake of the demonstration, Reeves launched a fundraiser to support Scottish Black-owned businesses. The Black Scottish Business Fund has raised almost £15k, which will go towards providing grants and offering mentoring to businesses alongside other forms of support. The fund will undoubtedly empower Scotland’s Black community through the creation of jobs; and even though the aims of the Fund aren’t overtly political, it’s hard to ignore the potential for Scotland’s emerging community of Black-business owners to mobilise and invest in causes that matter to them.

Recent far-right demonstrations and violence in Glasgow have made clear that Scotland’s anti-racist struggle is far from over. To address these issues and work towards a country built on justice and equality, we will need a strong social and political movement. Finance is only part of this, but history tells us that creating an environment where Black-owned capital is encouraged to thrive will better equip communities to deal with the inequalities they face.

I would have thought there would always be a tension between private capital and any socialist movement it funded, and undue influence for major funders, and a weakness that could be exploited (assuming that the funder was genuinely committed to the cause, which is generally hard to prove). If we think how various Brexit-era campaigns were challenged on the basis of dodgy funding, or how many donors expect rewards for their investments in political campaigns, and how many astroturfing campaigns have been funded, there is enough bad precedent to give pause for thought. And of course, well, slaver philanthropy has been much in the news. When the rich meddle in politics, they don’t have to be a Crassus to do major harm, and surely it sets the wrong kind of precedent for a popular movement? The cult of the entrepreneur is one of those factors behind the rise of modern technological racism. Surely a lot can be achieved with volunteerism and grassroots donations, the loaves and the fishes approach?

Thanks for your comment. I broadly agree with what you’re saying: I do think we have to be cautious about wealthy individuals/corporations using their money to meddle in politics. However, perhaps the distinction I’m making is businesses/enterprises being set up to empower (in this case Black) communities and support their political/social movements. I don’t think the Black Panther Party, NAACP, Malcolm X etc. would have been able to achieve what they achieved without the private Black-owned capital that was set up to support them. That being said, I agree with you that volunteerism and grassroots organising should be the bedrock of any movement, but I don’t see that and the support of private capital as being mutually exclusive.

@Miles, thanks for your response; well in that case there should be a best practice guide, perhaps including transparency and lack of strings-attachedness. In some cases, I am thinking of humanitarian funding, the problem has been money pledged and then never delivered. I imagine that the breadth of funding across the USAmerican civil rights movement (I assume Martin Luther King’s wing drew a lot on church funding?) gave it more of a base and made it more difficult for outside interests to steer.

On pan-Africanism, I read that the pandemic response seems to have brought forward some integration plans, in finance and public health:

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/jun/22/the-power-of-volume-africa-unites-to-lower-cost-of-covid-19-tests-and-ppe

That doners might attempt to influence is almost inevitable; how else could it be? It remains the case that no matter how many jumble-sales or raffles you care to organise, none of the traditional fund raising methods have achieved very much in the way of social transformation over the years. That’s not to argue that community generated funding initiatives can’t have an important role to play in locally specific campaigning efforts.