Iman Tajik’s ‘Bordered Miles’

Interview with artist-activist Iman Tajik at the time of his current exhibitions: ‘Bordered Miles’ (Listen Gallery, Glasgow International Festival); ‘The Dreamers’ (Stills Centre for Photography, Edinburgh); ‘Calais’ (Stills Centre for Photography, Edinburgh); and ‘This Is Now Not For Me’ (Journeys Festival, Online). By Sophie Suliman.

Through his current work, Tajik continues to enquire into ideas of borders, migration, and nationality – informed by his own experience in the UK immigration system. He uses his art to raise awareness of such systems of injustice and advocate for equality and human rights for all.

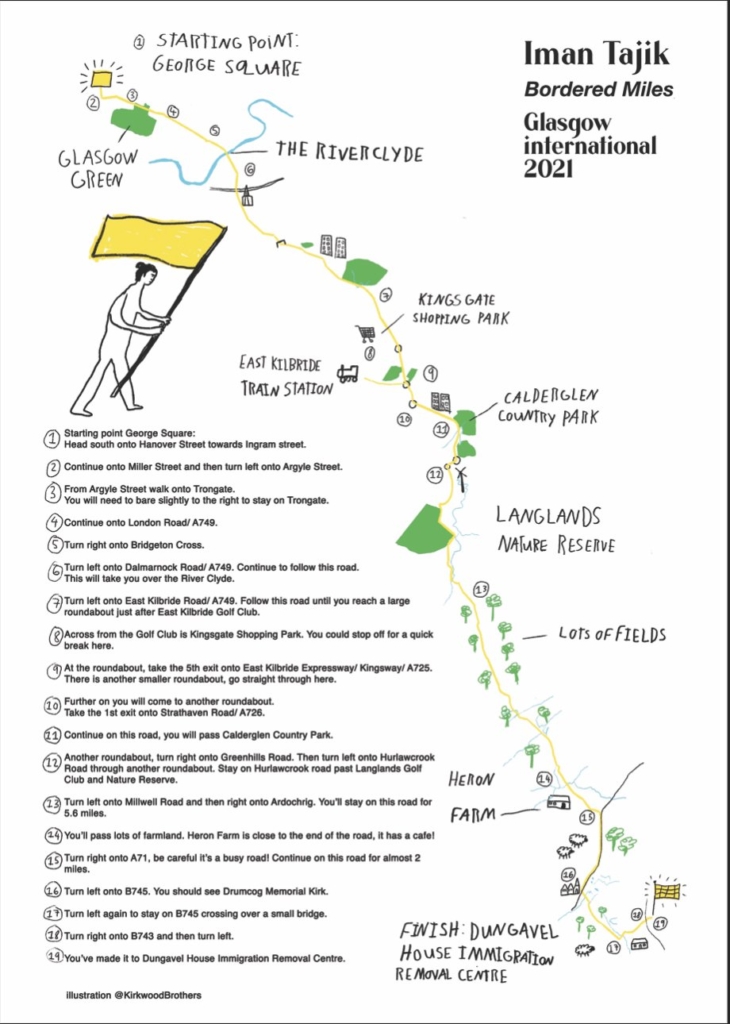

Bordered Miles is an installation depicting a raised flag, made from a survivor emergency blanket, with a Scottish backdrop. The blanket is the same as those given to people seeking safety upon arrival to European shores. A walk from Glasgow to Dungavel Immigration Removal Centre on Sunday 20th June will also take place as part of this work, during which participants will engage in a series of reflective and performative tasks. Upon arrival, the flag will be raised outside the detention centre where Tajik was sent when he arrived in the UK.

The Dreamers forms part of this work and was developed during a residency with Deveron Projects in Huntly. It is being exhibited with images from Calais, a photography series based on his time in the makeshift site for those seeking asylum.

This is Now Not For Me was developed during the pandemic and demonstrates his recurring interest in borders in the context of lockdown restrictions.

I interviewed Tajik in the context of this work with a particular focus on Bordered Miles and his upcoming walk.

Borders, politics, and power are recurring themes in your work. Why did you make Bordered Miles and what is the significance of the flag?

I do not want to be prescriptive. I want the flag to open up conversations about nationality and migration. I want people to question the value, role, and roots of nationalism in emergency settings and to reflect on their own responses to these issues. I question nationality because of its association with borders. Borders divide; they are used as a tool for power and control, and can destroy freedom of movement which is a basic human right. Freedom of movement exists but only for some people. It depends on your passport – if you are European or British you can travel easily. If you decide to go somewhere for work, for the weather, for love, you just go. So many freedoms. For other people, it is not the same.

Why did you choose to facilitate a walk?

Dungavel Immigration Removal Centre exists because of borders and a lack of freedom of movement. When we walk, we travel from point A to B. We cross many invisible borders that have become more visible because of lockdown. City, town, and council borders. We walk all the time and cross these borders but are often unaware of these and our own movement within them.

How does This Is Now Not For Me link to these ideas and our experience during lockdown?

In this piece of work I explored freedom of movement in the context of lockdown. I felt it was the first time since the Second World War that Europeans had been denied freedom of movement. We were all locked in our houses, our council and national areas. I worked with tape to represent these borders.

In Listen Gallery, you have left hundreds of emergency blankets for people to observe and take home. What was your intention?

I wanted them to take something away with them and to know that anyone could be a refugee – that it could be them one day. People forget. They think refugees are only from the Middle East or Africa. But they do not remember the Second World War. There were so many European refugees around the world at that time. I think new generations have forgotten. People think this is not for them or it will not happen here. Maybe they are wrong. Look at your history. And the future. Scientists say parts of the UK could disappear because of the climate disaster. Forced migration affects everyone.

You talk about forgetting and remembering. How does this work connect with Scottish history?

The photography and videography within Bordered Miles and The Dreamers are set against a Scottish landscape, referencing the highland clearances in the 18th and 19th centuries; Scotland has a history of conflict and forced migration.

Why did you choose Dungavel as the destination for this walk, and how does it resonate with your own story?

The theme of the Glasgow International Festival is attention. I wanted to draw attention to Dungavel Centre, an immigration removal centre near Glasgow. It is in the middle of nowhere and people do not know it exists, or they lack information. I plan to put more information on the project website I am developing.

The detention centre is a prison. I was there. In other prisons, you go to court, you are heard by a judge, you have a lawyer, there is a jury. And a decision is made. At these detention centres, the Home Office sends you to this place without telling you how long you will be there. One month, ten months, a year, forever. There is no time limit. Children and adults are forcibly deported. People suffer in this place. Some hurt themselves to prevent deportation. Sometimes when people are sent back to the countries they came from, they end up in prison or killed.

Can you tell me more about your experience of living in the centre?

I was depressed. Constantly worried about what was going on and what would happen. I lived behind huge walls and barbed wire. They locked us in at night. I felt terrible because I had not done anything wrong; crossing a border is not a crime. I experienced so much trauma on my journey, and when I arrived in the UK I was sent to this centre. I was traumatised again. Even if you are only there for an hour you would leave a different person. I was broken.

What do you hope for?

A world without borders.

You can join Tajik’s walk from Glasgow to Dungavel Immigration Removal Centre on Sunday 20th June 2021 by booking a free ticket here: https://glasgowinternational.org/events/iman-tajik-2/. The walk will be live-streamed and a map is available if you would like to undertake the walk at another time.

Bordered Miles is being exhibited in Listen Gallery, Glasgow, until 27th June 2021. Please visit the link above to find out more. The Bordered Miles website is under development and available here: https://borderedmiles.com/About-Us

The Dreamers and Calais are on display until 19th June 2021 in Stills Centre for Photography, Edinburgh. For further information visit their website: https://stills.org/exhibitions/projects-20-iman-tajik/

This Is Now Not For Me can be viewed online: https://www.journeysfestival.com/2020thisisnownotforme

For more information about Tajik and his work visit his website: https://imantajik.com/

“I question nationality because of its association with borders. Borders divide; they are used as a tool for power and control, and can destroy freedom of movement…”

Good on ye, man! Nationality as a concept inherently discriminates, classifies, and privileges. Any action that facilitates the deconstruction of such borders between folk, and the relationships of power they express, is to be celebrated as liberating.

A world ”without borders” is an admirable idea – but , sadly , naive !

Not as admirable as the less naïve practice of seeking continually to subvert those borders, though. Mair pouer ti Iman’s elbuck!

‘Imagine there’s no countries, it’s easy if you try’.

Despite it’s cheesiness, I love the song. Trouble is, it isn’t that easy to imagine it.

Aye, but the task isn’t to abolish ‘countries’ (and analogous differences like sexuality and ethnicity) but to transgress the ‘borders’ between them.

It gives me hope that so much of the art of Scots like Iman addresses this task.

I think without any borders or nationalities, there are no countries really since how do you define where they begin and end and who is a citizen? They become names on a map but no mean little more, like the local ward boundaries all around us that most have no idea of their true nature and finding out their borders is very difficult. Everywhere you go people argue whether such and such a place in another larger place or its neighbour and no-one has an answer, or really cares. Country borders are very different.

My ideal is indeed no countries but it is a fantasy.

But I don’t disagree with you in general. There does seem to be a pretty big dissonance though between the idea of transgressing borders and questioning nationality, and nationalism. The article kind of glosses over this. In many ways Iman’s philosophy is the very opposite of nationalism, which always wants to both put up borders and strengthen existing ones, whilst defining anew who qualifies as a citizen in terms of their nationality, and who does not.

Yes, I believe the etymology is ‘[terra] contrata’ – ‘the land that’s spread before you’ – without any implication of political organisation. Like ‘Britain’ as distinct from ‘the UK’. People often get the two confused.

Citizenship goes with the political organisation rather than the geography; you’re a citizen of the state to the jurisdiction of which you’re subject, not of the country you inhabit. I’m ‘British’, inasmuch as I inhabit that archipelago, with local, national, and transnational citizenships, inasmuch as I’m subject to the respective jurisdictions of my local government, the Scottish government, and the UK government.

“I think without any borders or nationalities, there are no countries really since how do you define where they begin and end and who is a citizen?”

Except this is a fantasy that doesn’t exist – and Iman’s activism and artwork is specifically about the policies of the British state, which does exist.

I find his work more universal than that, Mike. But it is what you make of it.

Universal yes but he is walking to a detention centre run by the British state.

But how can you be a citizen without the geography in the first place? You have to have some legitimate connection to the defined, bordered place to be a citizen. It is true you can be a citizen without ever having lived in a place (I think) but your parents will have had to (or similar). The two concepts are mutually dependent.

Bella, yes point taken, though I agree with Colin – this is bigger than Britain / British. If all borders ‘divide; they are used as a tool for power and control, and can destroy freedom of movement’, then that can apply to all of them. He does say he wants a world without borders. New or renewed countries create more / harder borders.

What is relevant here to me is how does this map onto the current push for independence – how is this taken on board? Are the two incompatible or can it inform the way Scotland sees its relationship with the rest of the UK and the world? A land border cannot be avoided but its nature could really set the tone. That is one of the things Iman is raising in my head. It is a crucial question that is shoved under the carpet somewhat.

‘But how can you be a citizen without the geography in the first place?’

By citizenship being based on community of interest rather than on community of place. By a plurality rather than a unity of jurisdiction being allowed to obtain in any one place and free competition among jurisdictions within that plurality for our citizenship.

As I pointed out in my submission to the Smith Commission, a historical precedent for this *form* of antinational republic is the þing system that was operated by the Icelandic Free Commonwealth of 930-1262.

“Just as a territory can be divided into many small geographically distinct constituencies for the purpose of local administration and collective representation, so it might also be divided into analogous political units that have no territorial significance whatsoever. These might be called ‘virtual cantons’ or ‘commonwealths’.

“These virtual cantons or commonwealths would have two functions: representation at subsidiary levels of government and administration at the local level, with ‘local’ now serving as a structural rather than a geographical concept.”

I wonder from what material conditions such a republic might emerge. Perhaps it will be the globalisation of our social lives that the technological revolution in our productive forces has unleashed. Who knows where history will take us?

‘…how does this map onto the current push for independence…?’

Because the artwork can be exploited as something with which to beat the British state over the head in the ongoing grudge-and-grievance campaign to generate more support for Independence.

It’s a kind of reverse sublimation, whereby a work that speaks universally of ‘borders’ is reduced to just another local protest. It’s akin to reading To Kill a Mockingbird as courtroom melodrama.

You’re a sceptic Colin so that’s a given, but can a grudge and grievance campaign actually work? It is very good at preaching to the converted but for sceptics it can come across as simply ideological bias rather than reasoned argument. Transparent hatred of Britain (and the British state) will never convert those who do not hate Britain but might still think independence a potentially good idea. In fact it will do the opposite.

I just don’t know what the Scottish government has in mind when it talks about independence as our future state, so I can’t tell whether it’s a good idea or not.

Sometimes, it’s presented as a blank canvas on which we will be able to paint whatever future we like, which seems to ignore how power works in capitalist society. Other times, it’s presented as an absence of evil, such that life will necessarily be better without the malign influence of the Tories/Westminster/the English/whatever, which seems to ignore the fact that our social problems are structural rather than the caprice of an ever-changing cast of evil villains.

Neither of these sales pitches promises any real structural change (so as not to frighten Middle Scotland, whose votes the government will need if it’s going to win any future referendum), which begs the question of why we should buy independence at all.