Mutual Aid, Growing up in Public and Taking Care the Arika Way

What is Mutual Aid?

Mutual Aid is a guiding factor behind anarchist practice, and an essential framework for understanding anarchist views on social organization more broadly. So… what is it, exactly? Well… in its simplest form, mutual aid is the motivation at play any time two or more people work together to solve a problem for the shared benefit of everyone involved. In other words, it means co-operation for the sake of the common good.

Understood in this way, mutual aid is obviously not a new idea, nor is it exclusive to anarchists. In fact, the very earliest human societies practised mutual aid as a matter of survival, and to this day there are countless examples of its logic found within the plant and animal kingdoms.

To understand anarchists’ specific embrace of mutual aid, we need to go back over 100 years, to the writings of the famous Russian anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin, who in addition to sporting one of the most prolific beards of all time, just so happened to also be an accomplished zoologist and evolutionary biologist.

Back in Kropotkin’s day, the field of evolutionary biology was heavily dominated by the ideas of Social Darwinists such as Thomas H. Huxley. By ruthlessly applying Charles Darwin’s famous dictum “survival of the fittest” to human societies, Huxley and his peers had concluded that existing social hierarchies were the result of natural selection, or competition between free sovereign individuals, and were thus an important and inevitable factor in human evolution.

Not too surprisingly, these ideas were particularly popular among rich and politically powerful white men, as it offered them a pseudo-scientific justification for their privileged positions in society, in addition to providing a racist rationalization of the European colonization of Asia, Africa and the Americas.

Kropotkin attacked this conventional wisdom, when in 1902 he published a book called Mutual Aid: A Factor in Evolution, in which he proved that there was something beyond blind, individual competition at work in evolution. [from the Anarchist Library]

Neil Cooper talks to Barry Esson about the Arika organisation’s latest experiment in shared experience.

The cultural landscape looked a lot different from how it does now when Barry Esson first started putting on events at the start of the twenty-first century. This is evident from the three initiatives he and Arika, the socially-minded production company he heads up with long-term collaborator, Briony McIntyre, currently have on the go.

Already up and running at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London is Decriminalised Futures, an exhibition of thirteen international artists exploring experiences of sex workers. This is co-produced by Arika with the ICA and the Sex Workers Advocacy and Resistance Movement (SWARM).

Later in March, in association with CCA Annex, the digital wing of Glasgow’s Centre of Contemporary Arts (CCA), Arika will present A Breath to Follow. This two-day series of online discussions and presentations investigates different aspects of Black and indigenous grassroots art, dance and music collectives in Brazil.

This week sees the launch of Mutual Aid, a four-day online series of workshops, presentations and discussions based broadly around issues of care. These include events looking at issues including prisoner solidarity, drug user support, grassroots feminist movements, disability justice, and radical forms of care and creative collaboration.

Titles such as I Have Never Seen a Situation So Dismal That a Policeman Couldn’t Make It Worse, Neurotransgressive Fun Times, and Frequency of Touch: the Making of Motherhood set the tone of a programme outlined on Arika’s website at www.arika.org.uk.

“At the start of the pandemic there was a lot of talk about mutual aid,” Esson says of the thinking behind the event. “But I think that a lot of that gets recuperated back into our mainstream dialogue, and ends up really being quite a neo-liberal individualistic notion of charity, or something. Quite a lot of things that get framed as mutual aid over the last two years in the UK are actually quite charitable in their intentions, like a notion of giving, or something.”

Image Credit: Support Not Separation monthly picket, courtesy of Crossroads Women’s Centre Audio Visual Collective Image description: Support not separation picket where protesters hold up banners and signs for the support not separation movement. There are two large banners being held in front of a group of about 20 people. One banner says “stop universal credit cut! Take away our poverty, not our children”. The other says “support not separation, top snatching children from mums and nans”. Event/Context: Support not Separation: Legal Action for Women, Recovering Justice & Ubuntu Women Shelter, Sunday 13 March 1.30 – 3.30pm

Esson sees what Arika is doing is counter to such mainstream orthodoxies.

“Mutual aid is really simple,” he says. “I do something to help you out, and you do something to help me out. There’s a reciprocity to it. And I think there’s a trajectory within Arika’s work over the last decade, which is about self-determination in lots of different communities that we’ve worked with. With Decriminalised Futures at the ICA, that’s specifically sex workers talking about how they organise themselves, and what it is that they need in the world, prefiguring the world that they want to live in by the ways that they practice being in the world just now. Those notions of prefiguration and reciprocity are more radical undercurrents of mutual aid, which comes out of community organising, anarchist thinking, Marxist thinking.”

Like everybody else, Arika had live events curtailed by COVID, with one of their Episodes – mini festivals of discussions, presentations and performances themed around specific lines of inquiry – postponed four times. Arika’s Episodes have been the company’s prime focus over the last decade, with the shared experience of discussing ideas in person a vital part of the events.

Unable to operate in such a way, again, as with everybody else, they had to think creatively. This resulted in the decision to split the budget for the planned event in two, with half going towards a series of forthcoming publications, and half on what became Mutual Aid. For the latter, they looked to Local Organising, a network of individuals and groups from marginalised communities who are at the heart of much of Arika’s work, to take the lead. A steering group was formed, with Mutual Aid the eventual result.

“It was kind of like relating back to concerns happening in Glasgow through the pandemic, and coming out of it,” Esson says, “but also to long standing practices of community organising.”

Mutual Aid follows on from Arika being awarded a Turner Bursary in 2020. Along with nine other groups, this replacement for the curtailed Turner Prize for contemporary art saw them awarded £10,000. While this was for Arika’s work as a whole, it focused on Episode 10: A Means Without End, which explored maths, physics and collectivism. Arika distributed the £10,000 between groups such as Glasgow based charity, the Ubuntu Women Shelter, and migrant support organisation, The Unity Centre, also based in Glasgow.

Arika’s reach has also seen them host one of their Episodes at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The 2012 event looked at different practices of listening in various communities.

Image Credit: ‘Fourate Chahal, for Support. Don’t Punish’. Image Description: Colourful collage of drawings and photographs, showing support don’t punish messages and activists.

This spate of activity is a far cry from Arika’s roots as experimental music promoters. This initially came by way of Instal, a festival of ‘brave new music’ co-founded by Esson at The Arches in Glasgow in December 20012. This audacious calling card that accidentally kickstarted Esson’s adventures in events producing put left-field and experimental music, electronics, sound art and contemporary classical composers into the same room in a way that at the time was still rare.

Artists ranging from the orchestral-based Paragon Ensemble to improvised music veterans, AMM, to sound poet Henri Chopin and doyen of autodestructive art Gustav Metzger were seen as part of line-ups that seemed to shape-shift with each edition as the event’s hosts preoccupations expanded. At the time, only FreeRadiccals at CCA and Le Weekend at the Tolbooth in Stirling were operating with a similar sense of anything-goes expansiveness.

As Esson developed operations, Instal became a sort-of annual event, expanding to two days, then three. Another festival, Kill Your Timid Notion, became a fixture at Dundee Contemporary Arts, where film and multi media elements became a key part if the programme. Other one-offs followed. Resonant Spaces saw musicians tour sites of significant sonic properties. Shadowed Spaces explored did likewise in off-grid urban environments hiding in plain sight.

Somewhere along the way, Esson and McIntyre evolved into Arika, a name gifted them by Japanese musician Keiji Heino. All subsequent events since have been presented under the Arika banner. Depending on who’s doing the translation, the name can mean several things. One is ‘a secret hiding place’; another, ‘the location of all things’. The one Esson prefers was suggested by another Japanese musician, Taku Unami. His translation went deeper, suggesting it as ‘a place where maybe you might find the thing you desire’.

As a summation of the exploratory philosophy behind both Mutual Aid and Arika as a whole, the phrase is unlikely to be bettered. It also sums the sense of Esson, McIntyre and Arika having done their growing up in public over the last twenty years. Even in the early days of Instal, each event was shaped by whatever discoveries they’d made over the previous year and brought blinking into the light.

This led to Arika pulling the plug on Instal and KYTN and ditching any notions of running anything resembling a conventional music festival in their entirety. Experimental music festivals were springing up everywhere by now, anyway, and Instal had kind of served its purpose. Glasgow alone these days has Counterflows, Sonica and Tectonics, all of which arguably exist in part thanks to some of the doors opened by Arika.

Arika themselves were now more interested in the social, the political, and the shared experience. Each Episode was a mix of high theory, agitational ideas, and provocative performance from some of the finest minds from several generations. Black revolutionary poet Amiri Baraka came. As did SF writer Samuel R. Delaney, and many other speakers, thinkers and do-ers. Arika’s Episodes became forums to wrestle with the complexities and contradictions of art, life, and the marginalised cultures that exist within both. How the Episodes were presented in terms of challenging traditional hierarchical structures also became part of Arika’s gowing up in public.

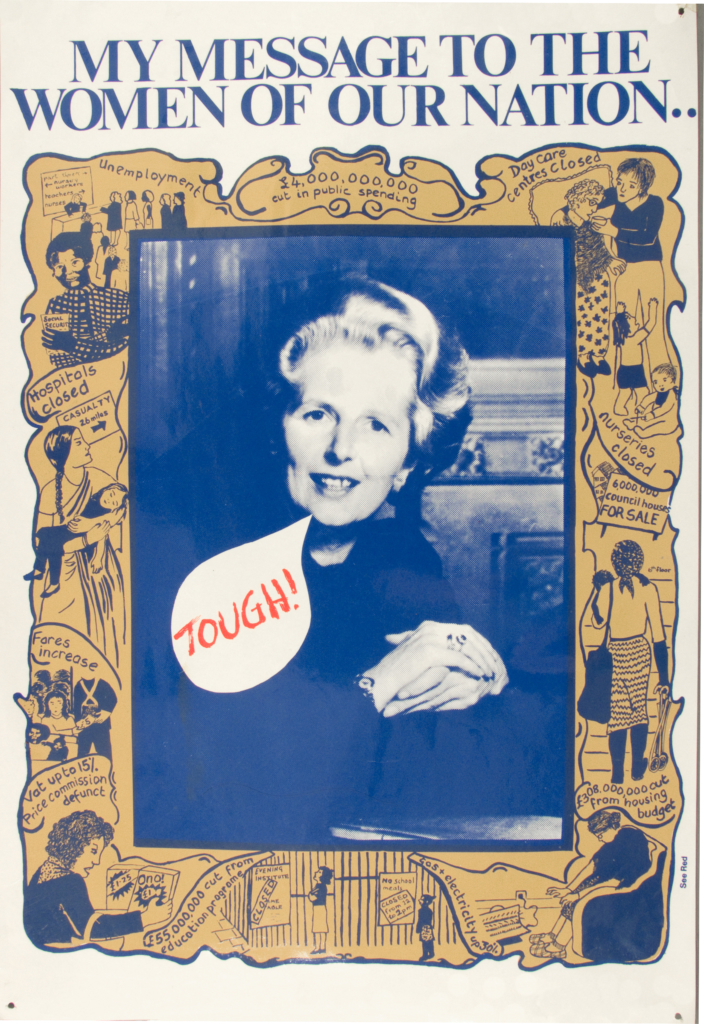

Image Credits: See Red Women’s Workshop, 1975, selected by Helen Charman

“When we stopped doing artform-specific festivals and started doing Episodes,” says Esson, “we were trying to make a conscious decision over what kind of discourses we were involved in, what kind of communities we were involved in; asking questions about who’s on stage, who’s at the sharp end of these particular political questions that we want to address, who has the experience of living with those oppressions directly?

Image Credits: See Red Women’s Workshop, 1975, selected by Helen Charman

“So you’re trying to think about who’s gonna’ be on stage, and the discourses that they’re having on stage. So it starts to initially look a little bit like a normative idea of representation or something. We started doing things with people like Fred Moten, and all the Black Studies scholars who were around; and the Ballroom community, who we’ve been working with for ten years. Those people being on stage, that’s one thing, but that maybe only gets you so far in terms of a fairly standard notion of inclusion in the arts.”

“Inclusion,” says Esson, “is super problematic, because inclusion only starts from a notion that there is a dominant culture that is feeling pressure from certain minority cultures. The way that it deals with that is to gate-keep, and allow some of those minority cultures into its dominance, so they’re always being included within the mainstream. That’s incredibly patronising.

“That also doesn’t recognise that mainstream dominant culture has been the culture that has been oppressing or killing or pushing down on those other cultural communities. And it also doesn’t recognise those cultural communities have their own culture, and it doesn’t go to meet them at the site of their own culture.”

Once Arika realised the potential of merely confirming the status quo in what might have ended up looking like some latter-day evocation of radical chic, a rethink was required. As Esson puts it, “As we’re educating ourselves through our Episodes, we are entangled with different groups in Glasgow. How would we meet them at the site of their own cultural production, as well as them being the people that are on stage, and presenting stuff at Episodes?”

Out of this, the Local Organising strand of Arika’s work was born.

“It started off quite small, and then we managed to grow the budget for a bit. So now there’s one person at Arika whose job is to deal with these specific community groups who we’ve been working with for five, seven, ten years.”

Esson doesn’t name the groups, not wanting to “claim cultural capital”. The various discourses ongoing, however, should become clear in Mutual Aid. Arika liaises with the groups regularly, and is able to offer resources to them they might not have access to without them. Arika is in receipt of regular funding from Scotland’s national arts body, Creative Scotland, and has received support from philanthropic organisations such as The Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

Esson sees Arika’s work as part of an ongoing organisational artistic practice. This seems to be confirmed, both by their status with Creative Scotland, and recognition by the Turner and the Whitney.

“There’s no other Scottish organisation that’s ever been nominated for the Turner Prize,” says Esson. “There’s no other curators to ever be nominated for it. So there’s things that we do that’s different from other people. But I think that’s also about expanding the notion of what the aesthetic is. Once you lose the weight of being artform specific, then we maybe also lose the weight of notions of what artistic practice might be, and maybe start thinking more about how we gauge the aesthetic registers of sociality. And by that, I mean by the ways that communities look and want to be seen, the ways communities move, or want to be moved, how they feel or want to be felt, how they listen or want to be heard.

“These still have an aesthetic register to them, but they also that also places them on us and more specifically, and political or social, social context. So that’s why Episodes are able to have this the mutual thing as an extension of it’s like an extension of Episode things, but with maybe even less art in it. You still talk about the aesthetics of these community practices and community organising, and how they come together, we’re still talking about how people want to be heard, and how they want to be seen.”

In keeping with the personal investment Arika has put into each of their projects over the last twenty years, the company has also produced a comprehensive online archive documenting each one. Going through it in historical order reveals an impressive body of work which itself has become a part of a history of oppositional creative thinking. Ask Esson how he defines what Arika is today, and what the most important thing about it might be, and, as ever, it’s complex.

“I was gonna’ say being useful,” he says. “There’s an element of it about how is what we’re doing useful. There’s also how is it recognising that there are a limited number of people involved in it, and that it is personal to the people who are involved in it. It’s not like we were established to be speaking on behalf of a whole community or a different sector or something. So, there are passionate elements to the projects, which are about what is driving us to try and be useful or generative, politically, ethically, aesthetically, with the resources that we have. But that’s not a very snappy soundbite.”A snappy soundbite would be counter to everything Arika is about.

“We’re still figuring it out,” Esson concludes.

Beyond Mutual Aid, A Breath to Follow and Decriminalised Futures, Arika has plenty of other things in the pipeline. In terms of long-terms strategies, however, Esson prefers things to evolve the way they have done ever since he put on the first Instal festival. He frames Arika’s possible futures by referencing its past.

“I still definitely take a lot that I learned from the theorisation of improvisation. Even if we’re not involved in experimental music so much anymore, I still have that schooling from speaking to people like Eddie Prevost, or Keith Rowe, and the whole of AMM, or jazz musicians like William Parker. You learn a lot from them about notions of improvisation, and how that’s helped collectively, without certain outcomes in mind.

“Through that,” Esson says, “I think that we have this kind of improvisatory, organisational practice, where we’re just trying to figure out how to use and access the resources that we have. Some of those are personal relationships, some of them are projects, and some of them are levels of visibility. Some of them are definitely levels of privilege that we have that other people don’t have. We’ve got to constantly ask ourselves about that and think about what we’re doing about that. We’ve definitely had criticism about that in the past, and we’re super-aware of that.”

Such self-criticism may be necessary to Arika’s modus operandi, but this too is part of its growing up in public. Like the improvising musicians who initially inspired Esson, the company has developed a loose-knit framework to operate inside, even if those involved don’t know exactly where they’re going.

“I think we have our practice and our way of doing things,” says Esson, “That changes when we work with different people, and then we just see what happens.”

Mutual Aid’s online programme runs from March 9th-March 13th. Full programme details can be found at www.arika.org.uk. A Breath to Follow takes place online at CCA, Glasgow, March 26th-March 27th. Full programme details at www.arika.org.uk. Decriminalised Futures is currently running at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London until May 22nd, www.ica.art.

Hi Neil just a wee thing, ‘survival of the fittest ‘ wasn’t said by Charles Darwin. It was Herbert Spenser. Huxley used it in effort to popularize Darwin’s ideas but Darwin’s favoured expression was natural selection. Cheers, Jim

Hi Jim – thanks for the historical corrective. Is that one of those misquotes that goes on? The mistake(and intro) is mine not Neil’s.

Aye, but Darwin later borrowed the term from Spencer and included it in the fifth edition of his essay on the Origin of Species.

They both used it to paraphrase the principle that variations that better adjust an organism to its environment are the more successful in surviving and reproducing within a population. Variations in the physical features of organisms that tend to benefit an individual (or a species) in the struggle for existence are preserved and passed on (or ‘naturally selected’) because the individuals (or species) that have them tend to survive. The success or failure of a given variation can’t be known when it emerges; it’s known only retrospectively, after organisms that possess it either grow and mature and pass it to their own offspring or fail to mature and reproduce.

This Darwinian principle builds on the Malthusian principle that the order of nature (what we later called ‘the global ecosystem’) is relative and not absolute, that ‘winners’ with respect to species within the ecosystem can become ‘losers’ (and vice versa) as a result of environmental change. The whole doomsday scenario of climate change is thus informed culturally by the ‘God-is-dead’ narrative of Malthusian relativism.

Darwin’s biological principle of the special evolution of life by natural selection rather than by design or purpose also builds on Adam Smith’s anthropological principle of enlightened self-interest and mutual aid: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.” According to Smith, the propensity we observe for altruism isn’t born out of some innate or God-given charity or goodness, as Rousseau would have us rather believe, but out of a calculated strategy of mutual aid, in which we get others to help us get what we want by helping them get what they want, to the economic and social benefit of all (‘You scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours.’). The ‘invisible hand’ of mutual aid – the metaphor for the mechanism by which beneficial social and economic outcomes arise by chance from the accumulated self-interested behaviour of individuals rather than by intelligent design or external regulation – is the same ‘invisible hand’ of chance by which arises the emergence and survival of myriad and ever-changing species of life.

Kropotkin’s ‘Mutual Aid’ is as much an application of Smith’s metaphor of ‘the invisible hand’ and a conclusion of Malthus’ ecological relativism in 19th-century political theory as Darwin’s ‘Origin of Species’ is in 19th-century biological theory.

Thanks, Jim.