Consultation on a Scottish Languages Bill

The Scottish Government have announced ‘A consultation on our commitments to Gaelic, Scots and a Scottish Languages Bill.’

The Scottish Government have announced ‘A consultation on our commitments to Gaelic, Scots and a Scottish Languages Bill.’

Read the full paper here: Ministerial Foreword – Scottish Government Commitments to Gaelic and Scots and a Scottish Languages Bill: consultation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

They state:

“The Scottish Government has made a number of commitments to the Gaelic and Scots languages. Among these there are four key commitments which can be regarded as particularly significant with the other commitments falling under these broad areas. The four key commitments are: to establish a new strategic approach to GME, to explore the creation of a Gàidhealtachd, to review the structure and functions of Bòrd na Gàidhlig (BnG), and to take action on the Scots language. Where primary legislation is needed for these, the commitment to a Scottish Languages Bill could serve as the legislative vehicle that will enable progress to be made with these commitments.

Over recent years there has been good support for Gaelic. A range of projects and initiatives have been put in place and important legislation has been supported in the Scottish Parliament. There has also been an increase in support for Scots and growth in resources available. With these new commitments and the growing evidence of support for these languages the Scottish Government would like to take additional steps in support of Gaelic and Scots.

The consultation paper will take each of the key commitments in turn, describing the key commitment and those subsidiary commitments which we consider as being connected to or falling under these broad areas. We will try to set the scene by providing a range of views that have been shared with us thus far through informal consultation with a range of stakeholders.

This is designed to stimulate further discussion, ideas and engagement with all relevant interests. No decisions have as yet been taken on how to make progress for Gaelic and Scots and we are actively seeking contributions from across all communities. We are seeking views on how further progress can be made and the views that we receive will assist in shaping the actions taken immediately and over the longer term to deliver on these commitments.

We are aware that there are links and interdependencies between the various Gaelic commitments. For example, it is likely that GME will feature in any discussion relating to the exploration of a Gàidhealtachd. Similarly, Bòrd na Gàidhlig has a role in relation to education; changes to education or indeed the exploration of a Gàidhealtachd will involve consideration of the functions that Bòrd na Gàidhlig should have to support changes in those area and therefore will overlap with the review of Bòrd na Gàidhlig’s own structure and functions.”

We invite readers to submit articles for publication prior to submitting to the consultation to contest and develop ideas.

- The commitment to Scots seems extremely vague (‘to take action on the Scots language’). What does that mean?

- The commitment to GME seems partial and contradictory. It states: “The aim of GME is for young people to be able to operate confidently and fluently in two languages as they progress from early years, through primary education and into secondary education.”

Yet only recently, the Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills Shirley-Anne Somerville MSP (who pens the Foreword to this consultation) has admitted that their will be no GME secondary school in Edinburgh as promised.

The Evening News reported: “Cllr Griffiths claimed Education Secretary Shirley-Anne Somerville had now acknowledged her department was unable to identify a viable site for such a school.” She told the council’s education committee: “At the request of he Cabinet Secretary I met with her purely to talk about GME and at that meeting she was very clear she had instructed her officials to look at a city-centre site and there wasn’t anything. She said she was going to meet with the parents and advise them of that.”

This means hundreds of children currently going through gaelic primary education will come out to no provision at all. - On the issue of the Gàidhealtachd the consultation notes:”The Highlands and Islands of Scotland has traditionally and historically been regarded as the Scottish Gàidhealtachd. However, in terms of the policy application of this term, there are differing views and responses. Some of these have been referred to below and these may help with responses to this consultation.Some regard the term Gàidhealtachd as a specific location to be geographically designated. They would see the aim of this commitment to be to strengthen Gaelic in geographical areas where it is spoken by a significant percentage of the population. The presumption being that there are certain areas where the Gaelic language has a higher profile and that certain language support initiatives should happen in these areas.At the same time a number of interest groups did not view the delivery of this commitment as a straightforward task. There were questions raised about how this commitment sat with the concept that Gaelic should be for all of Scotland and should be a national language. This was linked to the concern about ongoing support for Gaelic in other areas, such as Glasgow or Edinburgh, that might be defined as non-Gàidhealtachd. There were suggestions that this approach might be divisive, might be difficult for the allocation of grants and if a line was to be drawn on a map it would be difficult to reach agreement on the criteria for this decision.”

This would seem to set up a completely false dichotomy. The need for support and focus to be in the localities in which gaelic was strongest until recently is obviously essential, and to that end a strategic focus on a geographical Gàidhealtachd is required. That should mean – among a great many other things – gaelic medium education in all schools in that area. It must also mean recognising that language development and protection is intrinsically linked to social justice issues around affordable housing and jobs. Social cleansing is cultural cleansing.

But the idea that this commitment to a Gàidhealtachd should undermine the growth of new learners in urban Scotland where there is already provision is misleading. The setting of one ‘community’ against another is a complete distraction, they are and should be mutually interdependent. The only reason they are seen as not is a lack of financial and political commitment.

The paper seems vague to the point of omission about the dire language problems we face, there needs to be a much stronger sense of urgency and dynamism in the strategy, and this must be manifest in a significant increase in funding at the heart of any new Language Bill. We welcome readers input.

You can submit your articles on the Gaelic, Scots and a Scottish Languages Bill. here: Contact Us – Bella Caledonia

I have just got COVID. But this is very important. I will comment tonight as best I can,. Thanks for taKing this initiative, Mike

What are these ‘dire language problems’ we supposedly face? And why are they ‘problems’?

Well the problems are very different for either language. The problem for gaelic is catastrophic loss in the historical heartlands as recent surveys and reports have highlighted in detail. I think this is a problem because gaelic language and culture is an intrinsic part of Scottish history, identity and landscape and the loss of language is not just a shift towards a monolinguism and that narrowness but irreparable cultural loss.

The problem of the loss of Scots Gaelic is real and serious. The solution is to promote a rolling programme of free courses in studying, learning and practising Scots Gaelic, with an associated programme of free cultural events, for all adults over school leaving age throughout Scotland. Not online. That’s just a form of privatisation. In real community adult learning centres. Every School. Every College. Every WEA branch. Every Community Centre. I will join straight away. Been meaning to learn Gaelic for years. This is something we could all get our teeth into.

Not another national consultation for Christ’s sake.

“The solution is to promote a rolling programme of free courses in studying, learning and practising Scots Gaelic, with an associated programme of free cultural events, for all adults over school leaving age throughout Scotland.”

I’d be all for that, providing that the state promoted equivalent programmes for the advancement of Urdu, Punjabi, Arabic, and every other minority Scottish language. Gaelic shouldn’t be privileged in this respect. The decolonisation of – and the integration of all our communities into – the institutions of civic life that define our nationality as ‘Scots’ requires nothing less.

I’m not sure what’s meant by the ‘loss’ of Gaelic’s ‘historical heartlands’. Surely, what Gaelic’s lost is its users.

Gaelic is indeed an intrinsic part of Scottish history; so is it’s decline. As for Scottish identity, there are five-and-a-half million Scots nowadays; hardly any of them use Gaelic. In what sense is the language and culture intrinsic to their identity?

All that the various ‘ethnicities’ that make up ‘Scots’ have in common is their shared participation in the civic life of the same imagined community. Gaelic is no more intrinsic to our nationality nowadays as Urdu, Punjabi, or Arabic is. (This latter is one of the essential points that Raman made in her article on The Bowling Green.)

You don’t know what is meant by Gaelic’s ‘historical heartlands’? Er, ok.

There is no conflict between promoting/supporting multicultural Scotland and gaelic. None.

No, what I don’t know what’s meant ‘loss’ of Gaelic’s ‘historical heartlands’. Last time I looked, they were still there. What those lands are losing (and have been for a very long time now) are their Gaelic users.

And there’s no *necessary* conflict between creating a multicultural Scotland and promoting Gaelic, but there is a conflict between creating a multicultural Scotland and promoting Gaelic language and culture as something that’s intrinsic to Scottish identity. All that’s intrinsic to Scottish identity is a shared participation in the civic life of the nation, whatever language one uses or whatever cultural or biological heritage one owns.

It’s tiresomely pedantic … okay to clarify I didn’t mean that Skye and Lewis had disappeared ffs.

Gaelic language isn’t ‘intrinsic to Scottish identity’ (whatever that means.

The idea that place has no cultural history is just stupid. The vast expanse of Scotland is covered with gaelic placenames, our hills and rivers can’t be known without language, and understanding language and culture loss is to understand power and landed power and the relationship to the British state.

‘Gaelic language isn’t ‘intrinsic to Scottish identity’ (whatever that means[).]’

It was you that said ‘gaelic language and culture is an intrinsic part of Scottish history, identity and landscape’.

And, certainly, places do have cultural histories. The rise and fall of Gaelic language use is part of the cultural history of many places. And, yes, that cultural history has been driven by changes in economic power relations. I wouldn’t dispute any of that. I do dispute the idea, however, that some Scottish languages (like Gaelic and Scots) should be privileged over others (like Punjabi and Arabic) as being somehow ‘more Scottish’ and given preferential state support on the basis of that privileging.

‘Tiresomely pedantic’ I know, but vital to a future decolonised and pluralistic Scotland.

Place and culture literally becomes meaningless under your worldview.

Okay 221101 – so this thread is about contributions to the ‘Gaelic and Scots Languages Bill’, and your suggestion is you want equivalent funding of Arabic. That’s very helpful and interesting, thanks.

The contact for you to submit your fascinating ideas is here: https://www.gov.scot/publications/consultation-scottish-government-commitments-gaelic-scots-scottish-languages-bill/pages/8/

‘…your suggestion is you want equivalent funding of Arabic.’

That’s not my suggestion, Mike. It’s more that Arabic etc. should, for the reasons I’ve given, enjoy equal rights and status to English, Gaelic, and Scots as Scottish languages (and that this should be guaranteed by a Scottish Languages Bill).

As usual your arguments prove nothing but your own stubborn and wilful ignorance regarding history. Your Dunning-Kruger effect is showing old man, put it away eh?

Of course my cognitive biases are there on display. My whole praxis consists in weaving systematic patterns of deviation from normal judgement or ‘received wisdom’.

We each create her or his own ‘subjective reality’ from her of his own perception of what we normally assume to be objective inputs, and its one’s construction of reality, not the objective input, that dictate one’s behaviour in the world. Thus, out cognitive biases may sometimes appear as perceptual distortions, or inaccurate judgements, illogical interpretations, or what is more broadly demonised as ‘irrationality’ or ‘mental ill-health’.

Although such cognitive biases may be dismissed and marginalised aberrations by ‘normal science’ or ‘common knowledge’, they can help us disrupt dominant ideologies and the relations of production or value-creation those ideologies express. Unconventional thinking, in other words, frees our minds from the ideological ice in which they’ve become stuck and thereby assist in our navigation of life.

Cognitive biases are presumably adaptive and therefore healthy. Cognitive biases may lead to more effective actions in a given context; that is, to better problem-solving. Alternatively, they may be a ‘by-product’ of our information processing limitations (what some cognitive scientists call ‘bounded rationality’) and/or of the impact of the ‘embodiment’ of an individual’s cognition (her/his constitution or biological state).

A continually evolving list of cognitive biases, including The Dunning–Kruger effect, has been identified over the last six decades of research on human judgement and decision-making in cognitive science, social psychology, and behavioural economics. They have all sorts of practical implications for our language-use and our social practice more generally.

That said, I don’t see any wilful ignorance in regarding the rise and decline of Gaelic as an intrinsic part of Scottish history going forward or in regarding that decline as a consequence a long-term collapse in the number of Gaelic users.

There is a particular problem with Scots. There are considerable variations in different regions of Scotland. An outstanding solution was provided by the scholarly W.L. Lorimer in his ”The New Testament in Scots (Southside, 1983) where he very cleverly allowed Christ’s disciples, who came from different parts of the country, to speak in their own regional dialects. Unfortunately, many of these dialects in Scotland have become adulterated over time. with a considerable loss of vocabulary, especially in rural areas by modern communications. This would require a concensus among local dialect speakers about what is still valid Not being a Gaelic speaker, I do not know whether here is a similar problem with gaelic variations.

The claim that there are considerable variations in different parts of Scotland presumes that there’s a standard of which they are variations. The Scots language has never had such a standard; one of Lorimer’s aims on making his New Testament was to provide such a standard, as the King James Bible had provided for English. Despite Lorimer and the labours subsequent lexicographers and grammarians, speakers and writers of Scots have happily proved resistant to the idea of a standard Scots language and variations thereof.

That there’s no standard or single Scots isn’t a problem unless, of course, it bespeaks the absence of a shibboleth around which an ethnic nationalism can be constructed. It’s perfectly possible for a language to coalesce around a plurality of conventional usages that bear only a greater or lesser family resemblance to one another in their content and structure.

From the perspective of the civic nationalism with which we should be seeking to inform a future Scotland, there’s also the consideration that increasing numbers of Scots no longer claim English, Gaelic, or Scots as their primary language, and we should be wary of a state that seeks to privilege Scotland’s so-called ‘indigenous’ languages and language-communities over those of Scots of non-indigenous heritage in our increasingly cosmopolitan and pluralistic society.

We should all speak RP. That would sort out the problem.

What problem? In Scots, there is no Received Pronunciation, let alone any traditionally accepted standards of vocabulary, grammar, and style. Why’s this a ‘problem’ that needs to be ‘solved’?

“Why’s this a ‘problem’ that needs to be ‘solved’?”

If it isn’t solved soon I would predict a slow, gradual death of Scots over the coming years. Without any centralised body promoting a unified vision of the language (like that which occurred for the development of most major languages) I fail to see any future for Scots or Gaelic. We’re becoming increasingly Americanised. Pop culture is marvel movies, netflix shows and whatever’s on the BBC. These form the early experiences of socialisation in our youth. In terms of serious literature, the last guy who got famous writing in Scots was Irvine Welsh back in the 90s. Not much else outside of that ever reached a mass audience.

What we need to save any semblance of “traditional Scottish identity” in the coming years isn’t going to happen. The children of the Gaels and Scots don’t care about their native language. They care about moving to London, getting a job a software engineer, watching love island on the weekend, mindlessly scrolling on tiktok whatever the fuck. It’s over. We’re all part of the anglo-american empire now, and any vestigial accent quirks are exactly that. Vestigial. Superficial and never to be developed or used again.

Scots are too preoccupied with moving up in the world and speaking the vernacular of the media empires surrounding them. Gaelic speakers, while having a language distinct enough to avoid assimilation, are few and far between. They’ll never pull of what Israel achieved for Hebrew.

Doric is very, very different to Lallands, and it always has been. Doric is so formally set that there are have been regular Doric columns in the P&J and even the Scotsman since time began. They would be a bit like deciphering Latin for someone who only speaks Glaswegian. Of course no language stands still unless it is dead.

As soon as elected politicians and state bureaucracies start to become involved prescriptively in matters concerning the languages we write and read, I begin to feel a little concern and wonder what is going on and why. I am grateful to Mike for inviting comments, which I will keep brief. First, I take exception to the the use of the term “the Scots language”. I would argue that there is no such single thing. The late Tom Leonard attacked and satirised the very idea of prescriptive Scots in many of his works. One of his main points was that many of us use a variety of spellings of many of the words we use, and that that was a desirable state of affairs. Save us from a new generation of Scottish or even Scots grammarians! Second I regard myself as a Scottish Internationalist first and foremost, and take the strongest exception to the apparent exclusion of English from a list of valued Scots languages. In English I include as a matter of course what Jim Kelman has called Scottish English. Thirdly I object to the leaving out of any list of the languages we should be concerned about of the languages used in Shetland , Orkney, the Western isles (outer and inner), most notably traditionally but also as a result of recent in-migration. Finally, and in conclusion I would like to make three linked geographical and cultural points: first, the greater part of the Scottish population lives in that area of Scotland which was for centuries part of Northumbria. In origin they are Anglo-Saxons. Second, a hugely important part of the population of Scotland came to Scotland from Ireland, often to avoid starvation, over several centuries. In origin they are Celts who spoke Irish Gaelic and Irish English. And third, the Scots spoken throughout all the parts of Scotland in which I have lived varies widely in sounds, spelling and sources of origin: just in the same way as the English spoken in all the parts of England in which I have lived. For some reason the word “pluralism” is floating about in my mind. I can’t think why.

“the greater part of the Scottish population lives in an area that used to be in Northumbria” – ie. Anglo-Saxon.

This is incorrect. The old kingdom of Northumbria went up the east coast to Edinburgh but did not include the kingdom of Strathclyde that stretched from Dumbarton to Cumbria. Strathclyde was predominantly Welsh speaking until the eleventh century whilst gradually becoming Gaelic. St Mungo, the patron saint of Scotland’s largest city, Glasgow, was a Welsh speaker.

I’m not suggesting that Scotland should promote Welsh as a native language (although it could: the earliest greatest Welsh poems were written in Scotland). I just wanted to correct the idea that the majority of Scots have Northumbrian linguistic roots.

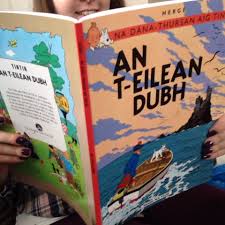

Tintin and Asterix – certain volumes – are both available in Scots; not sure about Gaelic as I’ve never looked for them.

‘The commitment to Scots seems extremely vague (‘to take action on the Scots language’). What does that mean?’

It means that they don’t even know what they are talking about, or they are being disingenious. It’s Scots languages plural. There isn’t a ‘Scots language’ singular. I think that being truthful would involve decentralisation and localisation. It doesn’t look like anything in the Scottish government would ever want anything like that.

Pluralism is the key to all of this. The ‘nationalisation’ of languages like Scots and Gaelic is inimical to the sort of cosmopolitanism that’s an increasing feature of Scottish society. Much more localism (cultural as well as geographical) is required if all our language communities are going to flourish and the imagined community of ‘Scotland’ is going to be decolonised.

Happy to agree with everything 221101 has said.

Can I add one last word? Has it occurred to anybody else to ask the question: why does there seem to be such an outburst of violence across the world, at the level of individuals, families and communities, but also at the level of continents, and in large societies, like the USA, Russia and China. I believe that against this backcloth. Scottish linguistic, cultural and even religious traditions have much healing power to offer. What is happening at the large-scale. broad-grain levels is this: information technology (in alliance with big capital), is driving out the people. As Brecht wrote: would it not be better, in these cases, for the government to abolish the population and elect another?

I’m just happy that you’ve not misunderstood what I’ve said!

I also suspect that it’s ‘the curst conceit o’ bein’ richt that damns the vast majority o men’ to be perpetually seeking to impose their own wills on others, even to the extent of violence. In pluralistic societies, everyone and no one is ‘right’.

I find your arguments specious, 221101. Under the guise of decolonisation and pluralism, what you propose (for the Scottish Government to eschew all national responsibility for them) would simply accelerate the disappearance of Scots and Gaelic as living languages, thus achieving what was once an explicit aim of some of Scotland’s ruling elites.

French happens to be my native language (strange, I know, given my name). There is a historic link between Scotland and France, visible in some place names in Edinburgh; and there is a thriving French community in Scotland. Yet I feel no need for the Scottish Government to take any steps to support this community through the kinds of measures contemplated in the present consultation, for example, French medium education in specially created schools. (This is quite different from placing greater emphasis upon language acquisition within the Scottish school curriculum, which I would strongly support.)

The reason is obvious: French as spoken by Scotland’s French-speaking community is not under the kind of threat that Scottish Gaelic is. Nor would I expect the French Government to take special steps to support Scottish Gaelic in France (though it should most definitely support Breton, for example). The Scottish Government, on the other hand, has a special responsibility to do so: because no other government will.

I am no expert on what policies might work to support Scottish Gaelic and Scots – and evidently neither are you, 221101 – but I would really like to hear from those who are. Thanks, Mike, for at least trying to get this discussion going.

Thanks Paddy. We have some serious contributions from people who have worked for a long time in communities to protect and develop language. These will be coming as part of a mini-series over the next wee while.

I haven’t proposed anything, Paddy; I’ve simply suggested that English, Gaelic, and Scots have no special claim when it comes to Scottish identity and nationality.

I’m currently working on a response to the Scottish government’s consultation on a Scottish Languages Bill that, on the basis of the foregoing suggestion, will further suggest that the Bill should guarantee that no language community in Scotland is discriminated against in and/or by our civic institutions, particularly on the dubious grounds that it’s to be considered less Scottish than our so-called ‘indigenous’ language communities.

Of course, Gaelic and Scots language communities should be supported in their struggle to survive and prosper in their identities going forward, But, in a multilingual society like our own, they can’t be privileged over any of the other language communities that make up the nation. To be just, any legislation that’s proposed would need to assert and guarantee that equality.

The Numbers guy/gal is a candidate for Pseuds’ Corner.

Indeed, pseudonymity has been a long-standing conceit of mine.

Well Mike I agree ,with you though it’s ah a wee bit oer ma heid, seems tae me some folks are sayin tae ye , you say black an I’ll say white

Language shapes what we are, how we think. When a language goes, so does a type of person / thinking. In other words I think it goes beyond what we call culture, or perhaps rather, is at the very heart of it. Even in translation some of this survives (I am thinking of translations of Welsh medieval poetry I have read that though in English, do not sound like the kind of poetry an English speaker would ever write).

This does not mean a language has some kind of right to survive but we do well to help it do so if possible. Pluralism and multiculturalism means there are inevitably competing agendas but discussions of Urdu and Arabic seem wide of the mark since those languages are not remotely in danger of extinction, not even in Scotland.

And time matters. Whatever one’s view on what Scotland ‘is’ today and will be in the future, you cannot erase over a thousand years of history and say it doesn’t matter any more than very recent developments. And even if you think it does, very many do not and that is what matters. Is this implying a hierarchy of importance? The (harsh) truth is that I think does and we should be honest about that. Equally though, there is a sense of desperation regarding Gaelic that suggests it could be a lost cause and one must ask how much money and effort should one throw at it before it is declared so?

I have no solutions but what might help is a certain freeing of the language from what is maybe seen as the ‘owners’ of it. There seems too much deference to this. I only say this because of the stuff I have read on here where there seems to be real conflict between native speakers and those wanting in on it as it were. I think this has happened much more in Wales and so Welsh is doing better.

I think Niemand’s contribution is very helpful and integrative. The best way forward may be to transcend the dominance of a particular territory and its historic speakers and writers and readers of Scots Gaelic, which gave us and the whole world this wonderful linguistic and cultural inheritance. To extend it to the whole of Scotland and its speakers and writers and readers of all languages used in Scotland now. With an opportunity and a challenge to all of us finally to encounter Scots Gaelic in its own terms and begin to engage with it.

Indeed, a Scottish Languages Bill that encouraged and facilitated our engagement with the diverse range of linguistic and cultural inheritances that constitute contemporary Scotland as an imagined community – and not just English, Gaelic, and Scots – would be a welcome way ahead towards the creation of a fully integrated pluralistic society.

‘Throwing money at it’. Spot the right-wing cliche.

‘Spend’ if you prefer. The question is legitimate.

Yep, Heidegger put it nicely when he said that language is the ‘house’ of being; it’s where our living lives. Wittgenstein put it just as nicely when he said that the limits of language establish the limits of our world. Language makes the world a meaningful place; it domesticates it, gives it a structure and order that we can objectify as ‘reality’, takes away its wildness and makes it a ‘home’.

Pluralism and multiculturalism is the coexistence of different ‘homes’ or ‘realities’ within the same society. The trick is to ensure that the processes and systems by which we manage our social interactions (i.e. our civil and political institutions) enable a general harmony of constructive social interaction can prevail despite the diversity, dissensus, and dissonance of our coexistent realities, that our differences can be accommodated short of conflict.

This, for me, is the challenge and opportunity of independence: to turn the political process of leaving the UK into a process by which we transform our current singular ‘Scottish’ nation into a plural multicultural one in which our traditional ‘Scottish’ heritage ceases to define the nation and becomes only one inheritance in a society of many.

The Scottish government actually pays lip service to this vision of a future Scotland in its ‘One Scotland’ campaign, in which it makes all the right noises in relation to ‘equality for all. No one should be denied opportunities because of age, disability, gender, gender identity, race, religion or belief, or sexual orientation’ and to Scotland being ‘a diverse multifaith and multicultural society, committed to promoting one Scotland in which many cultures can thrive side by side’. However, in the noises it makes in relation to English, Gaelic, and Scot’s as Scotland’s national languages, it at the same time refuses to acknowledge or act on the need to decolonise our institutions of the traditional ‘Scottish’ heritage that dominates their ‘worldview’ and whose hegemony shapes the reality they institute.

No one is ‘erasing’ a thousand years of anyone’s history by calling for a plural multicultural Scotland in which our traditional ‘Scottish’ heritage ceases to define the nation and becomes only one inheritance in a society of many. On the contrary, such a call is for the decolonisation of an institution – Scottish history – to create space for the inclusion of other realities and the integration of those other realities into that institution.

There should be no ‘hierarchy of importance’. The ‘Scotland’ that Urdu constructs is no more of less important than the ‘Scotland’ that Gaelic constructs; Urdu users in our society are no less ‘Scottish’ than English, Gaelic, and/or Scots users. None should be privileged over any other in a plural, multicultural Scotland.