Languages do not “die”, they are persecuted: A Scottish Gael’s perspective on language “loss”

This blog post includes a linked audio file. Just click on the link below if you would like to hear the post read aloud. Scroll down to read the text.

Pòl air a’ mhachair ann an Uibhist a Deas (Paul on the machair in South Uist)

Two-thirds of the world’s 7000-7500 languages are Indigenous languages. One-third of Indigenous languages are experiencing language loss and “as many as 90% are predicted to fall silent by the end of the century” (McCarty, 2018, p. 23). However, languages do not simply “die”, nor do they magically disappear. All languages change over time, but language shift, endangerment, or “death” is not natural nor is it unavoidable.

Languages are endangered and threatened due to inequitable sociopolitical structures and deliberate processes of oppression, discrimination, and violence. In this BILD blog post, I will illustrate some of the causes of Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) language endangerment. Gàidhlig is an endangered Indigenous language in Alba (Scotland) with approximately 57,000 speakers, around 1% of the Scottish population.

Is mise Pòl Miadhachàin-Chiblow. ’S e Gàidheal a th’ annam. Rugadh agus thogadh mi ann an Glaschu, Alba. My name is Paul Meighan-Chiblow. I’m a Scottish Gael. I was born and raised in Glasgow, Scotland. I am in the process of reclaiming Gàidhlig, my familial language, as an adult learner.

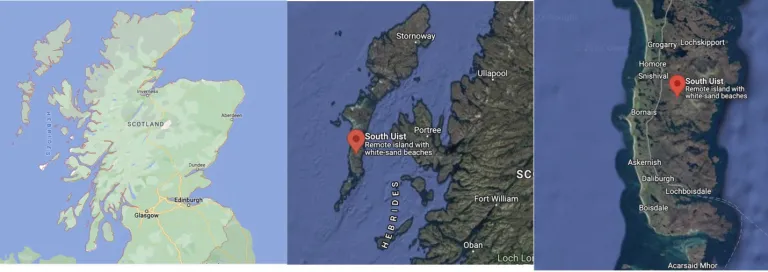

My worldview and experiences as a Gàidheal (Scottish Gael) growing up in Glaschu (Glasgow) inform my research and work as a critical sociolinguist. I was raised by my mother, Angusina MacGillivray, who is from the Gàidhealtachd, more specifically, Dalabrog (Daliburgh), in the northwestern island of Uibhist a Deas (South Uist) in na h-Eileanean Siar (Western Isles) (Figure 1). The Gàidhealtachd is comprised of the Gaelic-speaking areas of Scotland, also known as the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Uibhist a Deas is one of the heartlands of the now endangered Gàidhlig with some of the strongest Gàidhlig-speaking communities in the world, ranging from 62% to 79% of the respective community populations.

Figure 1: Map of Alba (Scotland), na h-Eileanean Siar (the Outer Hebrides), and Uibhist a Deas (South Uist) (Google, n.d.).

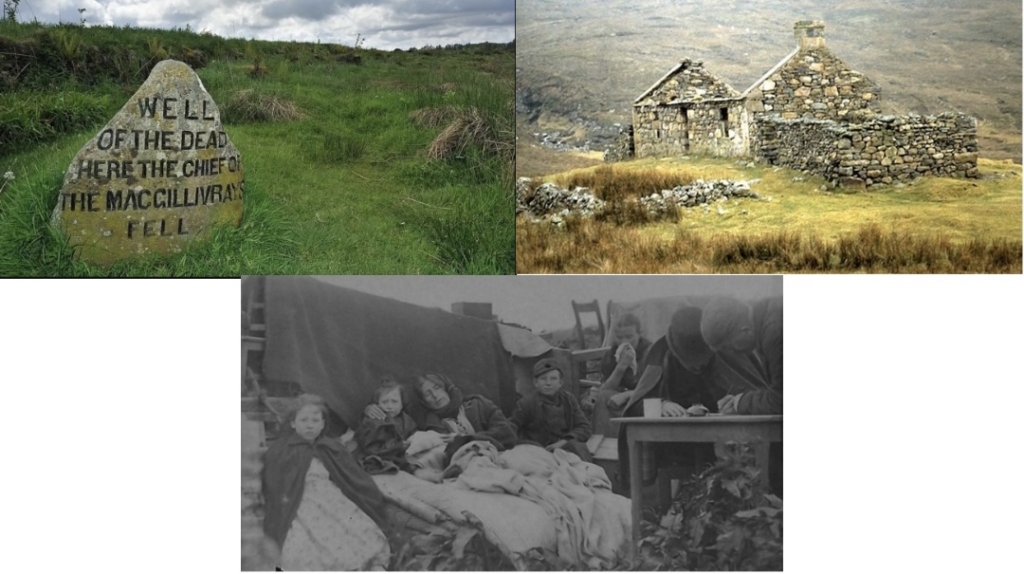

I would hear Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) all the time around my fluent speaking grandmother, Dolina Walker, who moved the family to Glaschu for work reasons when my mother was a teenager, and who lived down the street from us. However, Gàidhlig was not available to me in school. I did not understand why at the time, but now as an adult learner of Gàidhlig I do. Gàidhlig and Gaelic culture were almost eradicated due to many factors, such as the forced eviction of the Gàidheil (Gaels) from their traditional homes and lands during the Highland Clearances in the mid-18th to -19th centuries and the destruction of centuries-old Gaelic clan-based society after the Battle of Culloden in 1746 by British government and imperial forces (MacKinnon, 2017). Patrick Sellar in 1816 described Gàidhlig as the “barbarous jargon of the times when Europe was possessed by savages”, and John Pinkerton wrote of the Scottish Gaels in 1794 (quotes found in MacKinnon, 2017, pp. 35-38):

Had all these Celtic cattle emigrated five centuries ago, how happy had it been for the country! All we can do now is plant colonies among them; and by this, and encouraging their emigration, try to get rid of the breed.

The ongoing legacy of this coloniality of power is destructive in a myriad of ways. In the Gàidhealtachd the effects of clearance are still felt, with a fragile economy, rural housing crisis and the decline of the Gaelic language. In his essay, Real People in a Real Place, Iain Crichton Smith spoke of historical ‘interior colonisation’ alongside a growing materialism which, he believed, had left Gaels in a cultural milieu increasingly ‘empty and without substance’ …such a view resonates with…perspectives made by writers and scholars of indigenous peoples across the globe. This is not to suggest or promote an equivalence here between the experience of the descendants of enslaved people and others who experienced colonisation by modern, imperial states; rather, such perspectives describe symptoms of human-ecological disconnect, alienation and loss of meaning – an indicator of just how far our human psyche and culture has become divorced from our natural environments (p. 163).

Joseph Murphy (2009) writes,

It is widely accepted that Gaelic people in Ireland and Scotland have been through a colonial experience. Indeed, Gaels were amongst the first to experience colonialism and many of the policies and processes which would later become synonymous with it emerged in this context first. Although it is unrealistic to identify a series of steps or stages of colonialism it is possible to identify key characteristics or moments, such as the undermining of indigenous institutions, cultural stereotyping, and physical occupation…The replacement of existing governing institutions, negative cultural stereotypes, and the extension of formal control over Gaelic territory cleared the way for the full range of ‘ethnocidal policies’ (p. 24).

And Sorley MacLean, renowned Scottish Gaelic poet, talks about historical whitewashing in the 1974 documentary Sorley MacLean’s Island (extract plays from 2:34-3:34):

Ever since I was a boy in Raasay and became aware of the differences between the history I read in books and the oral accounts I heard around me, I have been very sceptical of what might be called received history; the million people for instance who died in Ireland in the nineteenth century; the million more who had to emigrate; the thousands of families forced from their homes in the Highlands and Islands. Why was all that? Famine? Overpopulation? Improvement? The Industrial Revolution? Expansion overseas? You see, not many of these people understood such words — they knew only Gaelic. But we know now another set of words: clearance, empire, profit, exploitation; and today we live with the bitter legacy of that kind of history.

As a direct result of deliberate processes of covert and overt linguistic eradication, family land dispossession, the role of the educational system, and internalized deficit ideologies about the “value” of Gàidhlig, I do not speak my language fluently yet. I am currently on a language reclamation journey as an adult learner since I refuse to be, as the Scottish Gaelic writer Iain Crichton Smith (1982) writes in Towards the Human, “colonised completely at the centre of the spirit” (p. 70).

As this short blog post demonstrates, languages do not just “die”. Rather, language speakers, cultures, and communities are deliberately persecuted, oppressed, and minoritized,either overtly or covertly. To this day, attitudes, ideologies, and policies still privilege dominant classes and languages at the expense of Indigenous and minoritized groups and languages worldwide. An example is colonialingualism (Meighan, 2022), the privileging of dominant and colonial languages as opposed to Indigenous, endangered and minoritized languages in education and policy.

In the case of Gàidhlig, Iain Crichton Smith answers the question “Shall Gaelic die?” with another question: “Shall Gaelic die! What that means is: shall we die?” This counter question necessarily centres the sociopolitical, ecological, cultural, and spiritual aspects of language “loss” and language reclamation where language is not just “words”. Indigenous languages are identities, cultures, lifeways, ancestral guides, ecological encyclopedias with linguistically unique and highly specialized place-based knowledges, and more. To be better informed about historical injustices and the causes of language endangerment globally is to be better informed about what we, in increasingly transnational and intercultural times, can do differently. This post is a call to start this process with a critical analysis and appraisal of the central role of language education in either perpetuating or preventing the erasure of Indigenous and minoritized language communities.

I leave this post with some questions for readers to reflect and act on:

- Which languages are taught or spoken—beyond tokenizing or superficial afterthoughts—in your educational institution?

- Are the languages which are mainly taught or spoken Indigenous to the lands on which you live, or are they colonial and non-endangered languages?

- How do the languaging practices in your educational institution challenge or advance the settler colonial project and the colonization of minds?

Tapadh leibh airson leughadh (thank you for reading).

Le gach deagh dhùrachd (with best wishes),

Pòl (Paul)

References:

MacKinnon, I. (2017). Colonialism and the Highland clearances. Northern Scotland,8(1), 22–48. https://doi.org/10.3366/nor.2017.0125

MacKinnon, I. (2019, Dec 4). Education and the colonisation of the Gàidhlig mind…2. Retrieved Dec 14, 2019 from https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2019/12/04/education-and-the-colonisation-of-the-gaidhlig-mind-2/

McCarty, T. L. (2018). Revitalizing and Sustaining Endangered Languages (J. W. Tollefson & M. Pérez-Milans, Eds.; Vol. 1). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190458898.013.10

McFadyen M., Sandilands R. (2021). On ‘cultural darning and mending’: Creative responses to Ceist an Fhearainn/the land question in the Gàidhealtachd. Scottish Affairs, 30(2), 157–177. https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.2021.0359

Meighan, P. J. (2022). Colonialingualism: Colonial legacies, imperial mindsets, and inequitable practices in English language education. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2022.2082406

Murphy, J. (2009). Place and exile: Imperialism, development and environment in Gaelic Ireland and Scotland. Sustainability Research Institute (SRI) Papers No. 17, University of Leeds. https://www.see.leeds.ac.uk/fileadmin/Documents/research/sri/workingpapers/SRIPs-17_01.pdf

Smith I. C. (1982). Towards the human. Macdonald Publishers.

Orignally published her with thanks Languages do not “die”, they are persecuted: A Scottish Gael’s perspective on language “loss” (by Dr Paul Meighan-Chiblow) | Belonging, Identity, Language, Diversity Research Group (BILD) (bild-lida.ca)

Can we not have some new ideas on what can be done to develop the Gaelic language and community rather than what is written here. There are 100’s of new ways and ideas worldwide on how you can change a linguistic situation from Hawaii to the Maori community and from Taiwan to the USA and Canada and Wales.

Why do we have to read these articles which give no hope at best when outside Scotland this is one of the best times for language development?

Have the writers no interest in what is happening throughout the world on this from or are they just ignorant when it comes to this subject.

Finlay, I’d encourage you (as the writer of the post) to read my recently available PhD dissertation on this precise subject of language revitalization and more equitable multicultural education, which also includes extensive reference to both very recent and previous work on these important topics worldwide.

You can find it here: https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/bz60d3092

It is titled “ What is language for us? The role of relational technology, strength-based language education, and community-led language planning and policy research to support Indigenous language revitalization and cultural reclamation processes”.

In brief, we co-created a series of fully immersive Anishinaabemowin language acquisition videos (now on YouTube) as part of an online community-led revitalization committee, which served as a self-determined community of practice. The TEK-nology (Traditional Ecological Knowledge and technology) approach I introduce could also be applied in Gaelic contexts. TEK-nology can support community-based and community-led networks among proficient/fluent speakers and learners to transmit both language and knowledge (encoded in Indigenous languages) about the local land, especially in these times of climate crisis. The links between language and land are already corroborated in natural and social sciences in recent years (please see the dissertation for the sources). Technology also enables speakers to reach learners more quickly and effectively (e.g., the fluent-speaking Elder on the TEK-nology pilot project highlighted that she can’t be in 10 places at once, for example, and technology helps her with that).

Another important finding in my research is a caution to not “copy-paste” formulas from other initiatives worldwide. While there may be, of course, excellent strategies that can be implemented, every context is and will be different. Initiatives that are truly community responsive must be contextual and based on specific needs which will be diverse across the Gàidhealtachd and globally. In short, the research seeks to center community members existing expertise in the language acquisition process and language-related decision-making and policy, something which could also be applied in Gaelic contexts.

Lastly, you are wrong. There is much to hope for in the post! I myself am a case in point as someone who is reclaiming Gàidhlig as an adult learner. That said, I believe the truth must continue to be told about why Gàidhlig is endangered and that it is important to look at the role of education is either perpetuating or avoiding the erasure of the language and culture (which I mention in the post, and I leave readers with some questions at the end to hopefully inspire discussion and action for implementing educational reform). Given the truth and bitter legacies mentioned by the great Gaelic scholar Sorley MacLean, Gàidhlig revitalization must also be trauma-informed, culturally relevant, community-specific, and community-led to address lingering colonized mindsets and deficit ideologies about the “value” of the language due to centuries of oppression, discrimination, and violence in Scotland (as mentioned in the post). For example, many youth who are reclaiming the language highlight this cultural and linguistic trauma. This trauma-informed work will, of course, be ongoing and is fundamental for Gàidhlig reclamation and revitalization. Lastly, I’m reminded of the renowned historian James Hunter writing in the book “Fonn ’s Duthchas: Land and Legacy”:

“If you’re informed by practically everyone in authority, as Highlanders were informed for so long, that everything about you, starting with your language, is of no account, then you’re bound to doubt your own capacities. That’s why, if it’s to be effective, developmental policy in the Highlands and Islands has to involve more than financial support…What’s required is a commitment to restoring the Highland population’s sense of worth. Hence our need in the Highlands to encourage both individuals and communities to take pride in their background; to make people feel good about themselves and their surroundings; to show that our area, despite the batterings it’s taken in the past, can offer all its people established residents and newcomers alike – much that’s of great merit.”

I wonder at times what all those people who write long articles about Gaelic have actually done themselves in terms to working in the various local communities throughout Scotland and what they have done.

There is no difficulty whatsoever in taking adults without any Gaelic to speaking conversational Gaelic in 6 weeks or less in Scotland (240 hours) yet in almost every situation the teaching methodology used is terrible and years behind the leading countries in this field as the Gaelic speakers continue to use the British Empire methodology for teaching Gaelic which was set out by the Scots to kill the Gaelic language and community yet this is what is still used.

They don’t seem to know how to build up Gaelic community anywhere in Scotland as they don’t seem to know the facilities that are required to do such a job. Once again they are years behind the leaders in this field. The list goes on. It is not any good looking back until you find the solutions to the way you can take people to speaking Gaelic or strengthening their Gaelic super-fast.

Are we not on the same side here Finlay?

After buying a copy of the newspaper and reading this article in its entirety in the National it struck home just how far behind Scotland is when it comes to reviving/revitalising the Gaelic language compared to other countries and their languages.

For example there were only 500 fluent Hawaiian speakers in 1982 and today in 2022 there are 33,000 families who use Hawaiian. They intend getting this figure up to 100,000 within 20 years and it is not difficult to see how they are making this happen.

In New Zealand among the Maori speaking population there were some 30,000 speakers in the 1980s and today there are over 130,000 fluent speakers mainly under the age of 20 years. They are working towards 450,000 fluent speakers or 75% of the Maori population over the next 50 years and can easily achieve this Goal.

I find it rather odd to hear from anyone in the education sector and interested in Gaelic and Gaelic revitalisation that they still don’t know how to increase the numbers of Gaelic speakers in Scotland or even seem to know how to create new Gaelic communities.

They must be stuck or live in a bubble and never leave it and this is not even going into the progress the Basque Community has made over the past 50 years.

How is it that this information is so available world wide but Scotland is so far behind in knowing how to revitalise the Gaelic language at each level of our political society and especially among those actively involved in promoting Gaelic?

Excellent piece. I studied Scottish Gaelic for two years with Duolingo and the BBC who have fingers in every cultural pie. I am having a break at the moment as I am finding it fiendishly difficult without a tutor. South Lanarkshire has no classes and that was even with a SNP administration. It has now reverted to a Unionist administration so no hope at all of such classes or tutors.

We need cultural detectives employed to detect the ways to face this situation and develop this beautiful language which belongs to the people of Scotland.

The development of Gaelic in Scotland has little to do with it being an SNP or Unionist administration. This is simply another excuse for doing nothing and patting oneself on the back for doing nothing. The SNP has done least of the political parties to develop Gaelic anywhere in Scotland and has indeed set things back in many places. Why anyone places any weight on what the SNP says it is going to do for Gaelic is beyond me as their record in Government shows clearly they are simply not interested in the subject and never have been.

They are much more English language orientated than the other political parties in Scotland though they prenend otherwise.

Writing about a dieing language in a different language very effectively illustrates how near to death the dieing language is. Gaelic Tumbler? Gaelic Facebook? Gaelic Instagram? Appart from Peppa Pig and maybe Morton vs. Cowdenbeath, is there anything particularly watchable on BBC Alba? You will need that, or it’s just virtue-signaling, and let’s face it – that’s not going to happen. Globalised media begets globalised language.

As the maps illustrate, Gaelic was a marginal language 120 years ago. Is it worth spend my money on trying to save it? (It would be an easier task if it had phonetic spelling instead of medeval spelling). I find it hard to care less because it’s certainly not part of my culture at all, that goes for the vast majority of people (99%?), and I don’t see how the World really is a worse place for a lack of Gaelic. Culture isn’t static – historical re-enactment societies are.

If your culture has become an historical re-enactment society it’s moribund.

BBC Alba has award-0winning tv such as Eorpa that is a far better current affairs programme than BBC Scotland.

“I find it hard to care less because it’s certainly not part of my culture at all” – I mean you are just showing your complete ignorance. Our entire land is named with gaelic placenames and it is an intrinsic part of our culture.

Naturally you would be of the same opinion regarding Scotland as it is now so completely part of the English language culture and British system there is absolutely no point in having independence. What is the point. Just let the Scottish Parliament disintegrate and die a natural death as Westminster can resume the whole power agenda.

Indeed it should give up all power to London and revert to London being the powerhouse when it comes to Scotland.

Perhaps you could use some of your money to learn how to spell English words properly?

LOLs

Learning Gaelic might improve your English.

Siuthad, feuch e. ‘Eil an t-eagal ort?

Come to think of it the Labour Councillor Bernie Scott made an enormous contribution in helping to open the Condorrat Primary Gaelic unit in Cumbernauld while Strathclde was still in place. He did not do it on his own as parents had been gathered locally who wanted a Gaelic medium Unit in the town and surrounding area. But he certainly helped to make it happen.

Thank you for the article.

My mother was born and raised in South Uist and was a native Gaelic speaker. She suffered corporal punishment and humiliation, like others, as a primary school child at the hands of the infamous Head Teacher, Lomax, at Daliburgh Primary School for speaking Gaelic. She became an excellent speaker and writer in English (she acquired lowland Scots later). However, when she could, she spoke Gaelic and, when she moved to Glasgow in the 1930s she found many in the Hebridean diaspora in the city and was able to speak her native language.

However, to her dying day she harboured a great resentment about the suppression of Gaelic. I remember, shortly before she died, her weeping bitterly about the cruelty she and her friends had experienced as children.

Contempt for Gaelic is still present in Scotland. It seems to be less than I remember when I was a child in Glasgow and experiencing bullying from some adult neighbours because my mother spoke Gaelic and, as a toddler, I did, too. Seeing this behaviour towards me, with great reluctance she decided she would speak to me only in Scots/English so that as my ability to speak improved I would speak in Scots/English and not suffer unpleasantness.

Can I, with humility, share my experience as someone who is English, living in England and an occasional visitor?

From my earliest trips to Scotland, to enjoy wialking and climbing, I was aware, from maps and signs, of being in a landscape which spoke a different language. It has been said before that the land talks to us in Gaelic. I also realised that many of the ‘standard’ place-names were essentially phoenetic approximations of the older Gaelic names. I was curious to understand better, and I discovered the meanings of, for example, Am Bodach, Aonach Beg, Coire na Ciste, Carn Mor Dearg, Tarbert, Even at this basic level, it has increased my understanding and appreciation of the landscape which surrounds me..

On the Ireland’s main radio station, RTE Radio 1, Irish words and phrases can be heard every day, interwoven with the mainly English speech. In contrast, it seems to me that, within Scottish broadcasting, Gaelic is ‘shut away’ in its own little room. I don’t listen to it regularly, but I don’t hear Gaelic on BBC Radio Scotland. Is shutting Gaelic away, so that people only encounter it if they make a conscious effort, actually a significant part of the problem? That’s intended as an open question, by the way. Thanks for reading.

I read some of your PhD thesis (mostly chapter 2), then bought and played Never Alone a beautifully rendered although occasionally mildly irritating cooperation-focused platformer (platform games are not my forté), which I completed so managed to view the majority of the culture insights (intriguing short video clips). English is a bridge language in the game. I would agree with your characterisation of games in the paper:

“Video games are also providing a rich medium that reflects traditions of oral storytelling with different strategies for language and cultural preservation and revitalization (Lameman & Lewis, 2011).”

I have previously mentioned Tchia in similar connection.

I think you may be a little hard on Tim Berners Lee’s development of the World Wide Web at the officially bilingual European research centre CERN (and if he is American that is news to me; I believe he is English). Perhaps you need a more reliable source, and there are plenty of those. English does function as a sub-layer in the sense of markup and programming languages to the web, but internationalisation was a major focus of the WWW Consortium, and there has been a lot of consideration of language, culture and localisation in the wider sense in the web technologies community.

In terms of collaborative game extension and development, natural languages, programming languages and markup are far from the only modes of communication, which is why digital literacy has been a concern for bodies such as JISC, but moreover there are languages of level-building for example which are conceptual and typically visual, so that communities of creators can collaborate without speaking the same natural languages, or using any programming languages or markup. I picked up a few Japanese terms as a byproduct of such engagement.

Of course, there are vital political lessons in gaming beyond cross-cultural fertilisation, such as the biocratic, non-hierarchical, communitarian worldview behind Never Alone, or shared insights into the psychologies of gamers (games are as much about behaviour modification as Surveillance Capitalism).

I think you also have to take into account language function and utility. I am aware of some deficiencies in English and the odd European language, but perhaps there are also some in Scottish Gaelic which makes it unsuitable for some purposes. I read recently that it has no words for Yes and No, which creates challenges for referendum questions, but I’m not a Gaelic speaker and perhaps some helpful tables of language comparisons would help the non-linguistic understand strengths and weaknesses. Someone has assured my that there are no obstacles to writing technical and scientific papers in Gaelic, but I have seen no evidence to back up such a statement.

Though at times and places imposed by force, the utility of English as bridging and sub-layer language should not be lightly dismissed; just as the deficiencies of languages like English should be clarified and exampled especially where other languages are considered complementary or having better solutions to communication problems.