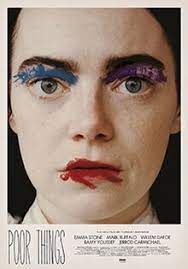

Poor Things

Why with the news that “Yorgos Lanthimos’ ‘POOR THINGS’ received a rapturous 8-minute standing ovation at the 80th Venice Film Festival” are we not happier? The film has had rave reviews, the Telegraph’s film reviewer said: “Poor Things is the best film at Venice this year so far and it isn’t even close.” The LA Times said: ‘Poor Things’ brings hot sex and Stone-cold brilliance to the film festival season”. The Guardian writes excitedly: “Poor Things is a steampunk-retrofuturist Victorian freakout and macabre black-comic horror, adapted by screenwriter Tony McNamara from the 1992 novel by Alasdair Gray and directed by the absurdist virtuoso Yorgos Lanthimos.”

“And his leading lady is someone who takes it to the next career level, or the level beyond the next level: Emma Stone. She gives an amazing and hilarious performance as the sexual-innocent primitive Bella Baxter, the secret experimental subject and ward of charismatic, troubled anatomist Dr Godwin Baxter (whom she calls “God”), played by Willem Dafoe.”

The film is directed by Yorgos Lanthimos and stars Emma Stone, Mark Ruffalo, Willem Dafoe, and Ramy Youssef. It will be released on 8 December in the US, 12 January in the UK and Ireland, and 18 January in Australia.

It may indeed be brilliant but it also exposes some real problems with Scottish cultural strategy which remains completely disconnected and grossly under-ambitious.

As Christopher Silver observed: “We may have one of the greatest screen adaptions of a Scottish novel on our hands – but lack the cultural infrastructure to properly mark this. Scotland has only two full time arts correspondents & one arts magazine programme. We’re reduced to hoping it piques London interest.”

This is true.

‘Poor Thing’s’ has become Yorgos Lanthimos film and Alasdair Gray, and Glasgow are absent from the phenomenon. This may not be a bad thing, Lanthimos has every right to interpret the work any way he likes and the book is a transcendent piece of work. It is not ‘about’ Glasgow and once it is born into the world it does not ‘belong’ to Gray.

The film may indeed be a triumph but it will be a triumph with little benefit to Scottish actors, directors, writers or film-makers. There seems to be little or no connection between our literary output, our writers, our producers, our actors and directors and any nascent film industry. We are an occasional location.

Contrast this with Ireland who this year were awarded 14 Oscar nominations. The crop of nominations was seen to be a reward for decades of investment across the creative industries. Where is the Scottish equivalent of The Quiet Girl (An Cailín Ciúin), the outstanding directorial debut from Colm Bairéad, where is the Scottish equivalent of (the disputed) ultra-bleak The Banshees of Inisherin?

This doesn’t come from nowhere.

In Ireland the audio-visual sector is currently worth more than €1bn to the economy, employing 12,000 people. According to the Guardian: “It has been pouring resources into it, both at home – where a huge new studio complex is due to open in Wicklow next year – and abroad: its film agency, Screen Ireland, last month signed a landmark agreement with France.”

The vibrant scene speaks of cultural confidence and investment. As the Guardian reports: “Its support for writers has created the lively literary culture that produced Sally Rooney, author of Normal People, a television adaptation which gave (Paul Mescal of Aftersun) his big break.”

Aftersun (2022) dir. Charlotte Wells

The numbers are stark: “The production spend on feature films, documentaries, animation and TV drama rose by 40% between 2019 and 2021, according to Screen Ireland, with international activity up by 45%.”

It may well be that we need to be an independent country to create this sort of investment. But film is Soft Power and Scotland suffers from negligent under-ambition despite having an arts scene that punches well above its weight overcoming terrible under-investment. We need joined-up-thinking and aspiration that unites cultural confidence with an understanding of the economic benefits that this will bring. The recurring whining about the Edinburgh Festival points to a sector that doesn’t feel at home with itself and that isn’t in charge of its own destiny.

What would the ‘cultural infrastructure’ that Chris Silver mentions look like? Some of it is really low-bar stuff. As Claire Squires detailed in 2019 the Scottish Review of Books imploded because it was run by people so off the pace that they didn’t have a clue (‘Patchy and Negligible‘).

So properly funding a quality review magazine (yes please) would be a minimal start. It’s not much to ask. Creating the ground for a vibrant arts culture starts from having more ambition than The Skinny or The List.

Properly funding the connective tissue between writers, theatre, tv and film is a no-brainer, instead of hoping for – then celebrating – big-budget movies to ‘land’ in Scotland as a location then pretending that is a ‘film industry’ would also be a start. Alasdair Gray was one of our greatest writers but we are also laden with contemporary writers and actors who deserve the treatment and support that Ireland has created.

Having just completed a book about Alan Sharp – and this comment is not a plug for it – I’d say that the successes of “Rob Roy’, ‘Shallow Grave’ and ‘Trainspotting’ were frittered away by poor decision-making in the period just after their making. The flaw lay with the kinds of films produced, and why they were chosen.

As Jonny Murray outlined in his thesis of 2006, the production teams and policies of the first wave were nuanced to each film. With the films produced after that, policies and teams were selected for other reasons. It was never going to work, and it didn’t. Sharp’s ‘Burns’ and ‘The Beach of Falesá’ still need to be made. If they were, we might have a national industry to be proud of. There’s little reason to hope they ever will be.

Eleanor Thom’s article in Bella https://bellacaledonia.org.uk/2023/06/02/if-you-dont-go-away-you-cant-come-back-rediscovering-the-writing-of-alan-sharp/ says more about the book. Chapter 6 describes the film opportunity we had, and how we missed it.

The Scottish government’s ‘Culture Strategy for Scotland’, which was last updated in March of last year, is indeed ‘completely disconnected and grossly under-ambitious’. The document itself is a fine example of a soulless bureaucratic language game.

The best strategy that the Scottish government could pursue in relation to our culture would be to butt out of trying to co-opt it as source of tax-revenue, inward investment, prestige/soft power, or as a national brand identity. Its strategy should rather be to let our culture emerge freely and organically, as cultures do, from the relations into which we spontaneously and haphazardly enter in our productive lives with the materials we work, the tools and techniques we employ in working those materials, and the worlds we subsequently spin around us. These relations can’t, without fatal distortion, be planned and managed or otherwise fitted to a bureaucratic policy and process.

Culture has never been more fertile in Scotland. There’s an unprecedented amount of work being cultivated, both work that’s conservative and work that’s transgressive of our cultural institutions/traditions. That work is being produced by makers all over the country and across the myriad classes of people who inhabit it. There’s also an unprecedented cross-fertilisation and re-mixing of practices (cultural ‘innovation’ and ‘evolution’) that’s reinvigorating of the whole. Such fertility or ‘culture’ can’t be administered by the cold, dead hand of bureaucracy.

Our culture itself has never been healthier, more diverse, more chaotic. It’s this activity and energy, this fertility, of our imagined community, the culture or form of life of our ‘nation’, from which the Scottish government‘s culture strategy is hopelessly disconnected.

Which, I suppose, is no bad thing. For who wants a planned, state-led culture, a culture that’s nothing more than a nationalised industry that produces branded but commensurable goods and services for consumers or ‘culture-vultures’ in martketplaces like the Edinburgh Festivals?

The best strategy that the Scottish government could pursue in relation to culture would be to pursue policies that remove the obstacles to its flourishing, the chief among which is its own bureaucratic interference in our productive lives.

No critical reflection of problematic aspects of the movie?

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2023/sep/01/yorgos-lanthimos-poor-things-fuels-speculation-of-sex-scene-return-to-cinema

No mention of the Scottish games industry? No suggestion that international cocreation may now be the norm for many kinds of high and low-budget works, and therefore the concept of a ‘national creative industry’ might be hopelessly outdated? No analysis that subsidies are another form of social cheating and are ultimately another reactionary form of patronage? No insight on how AI is impacting creative industries after gobbling up low-hanging fruit such as poetry?

“No suggestion that international cocreation may now be the norm for many kinds of high and low-budget works, and therefore the concept of a ‘national creative industry’ might be hopelessly outdated?”

This is an extremely good point. In this sense too, culture may be returning the ‘globalisation’ it enjoyed in the Middle Ages, before the invention of nation-states and its subsequent ‘nationalisation’; only globalisation on a much wider scale, which transcends not only ‘Scotland’ but ‘Europe’ also.

MacDiarmid’s ‘In Memoriam James Joyce. From a Vision of World Language’ and his modernist project ‘To Purify the language of the tribe’ perhaps?

Having not seen the movie I am in no position to make a critical reflection on it?

@Editor, with an ‘R’ rating, you are likely to share the status of non-viewing with many others. Not such an accessible movie as, say, Braveheart (typical global 15 classification) or Brave (ditto PG), or even The Bard’s Tale IV: Director’s Cut (2019 Video Game, 16). Something to think about if you are considering global impact and influence. Of course, you could have reflected on the content of the reviews and raised questions while withholding final judgement.

I’ll review it when I see it

Very good point about the games industry, may come back to that in a different article

@Editor, on the topic of the Scottish Games Industry, there is a sale on Steam:

“From thriving talent in Dundee to award-winning studios in Glasgow and Edinburgh, we welcome you to celebrate the incredible games being created and developed within Scotland.

“Scottish Games Sale is supporting Glasgow Children’s Hospital Charity’s ‘Games for the Weans’ campaign (Weans is our word for Children!). The funds raised will kit out the hospital with adapted gaming equipment, consoles, board games and supporting the hospital’s Play Team – so that children in hospital always have someone to play with.”

https://store.steampowered.com/sale/scottishgamessale2023

I can recommend Attack of the Earthlings.

Very good point about the games industry, may come back to that in a different article

To be fair The Guardian does not say the sex scenes in the film are ‘problematic’ merely that compared to a lot of recent films, it has quite a few. What it does do in typical Guardian style, is initially to try and taint it somewhat by referring to to other films (both very old) that were problematic in terms of their sex scenes (apparently) and mentions meToo and the fact that young people don’t have as much sex as they used to, all with not seeming relevance to this film at all. It also suggests sex scenes don’t really have a place in films any more despite the fact it is massive part of life and people’s motivations! The idea is ridiculous and indicative of a sort Victorian moralising.

I have not read the book – does it have a lot fo sex in it? Again the article doesn’t mention that because you can guarantee the author of the article (it isn’t a review) has not read it.

By the end it does talk positively about the use of an intimacy coordinator on Poor Things but overall I find the Guardian article misleading to the point of being dishonest, but it does not criticise the sex scenes in film specifically. Elsewhere in the same paper the film gets 5 stars.

When it comes to national film industries, plenty of countries still have them to the extent there is a kind of stylistic stamp about them even though international collaboration is more common within and outwith them. The latter does not preclude that stylistic bent. I am all for it as it is one of the reasons for watching some films, not least as an alternative to modern Hollywood’s fakery and hyped up fantasy garbage.

Decent point about video games though SD but you’ll never ‘get’ poetry if you think AI will replace it any more than it will replace other major aspects of human creativity. Have you come across the business of Stanislav Lem’s story from the 1970s about a machine he invented to write a (silly) poem with very specific and strange language and content requirements? The resulting poem is given in the story (which is all fiction obvs.). The requirements are very clearly stipulated and someone put them into an AI engine and guess what? It came up with the almost identical poem, not because it followed the instructions but because it copied Lem’s work. This is what this kind of AI is: a massive plagiarism engine that no doubt will fool millions of gullible people (it clearly already is).

“Again the article doesn’t mention that because you can guarantee the author of the article (it isn’t a review) has not read it.”

Man our entire website is based on the book FFS …

I meant the Guardian author, not you!

I’ll get my coat

Ha ha, no worries.

@Niemand, it may be that young people tend to see oversexualisation in cultural products (apart from erotica/porn) as manipulative, exploitative and reinforcing unhealthy stereotypes/tropes (including body image, or yet-another-old-male-mentor-and-young-female-ingénue) rather than being puritanically opposed to sex. It is rather obvious that sex sells, and the quality of works that depend on the attractiveness of actors is going to be less on the whole on works that stand on their own merits. Or perhaps some feel that the excesses are better confined to the world of fan fiction.

I agree that the kind of machine learning we tend to see, trained on vast corpus of literature or graphic art, produces a kind of neo-plagiarism. However, I think you underestimate how algorithmic constructions such as poems actually are, and other kinds of AI which use structural models can achieve output very similar to human artists. Things have moved on since the 1970s. And of course, poets are often little more than paid hacks, those seeking relief from writing therapy, manipulative conners, preening narcissists or social media influencers.

As well as poetry, earlier AI chatbots were able to mimic talk-psychiatrists with eerie accuracy. I’m pretty sure that AI religions will be even more convincing than the ‘real’ thing, something that I’m sure featured in science fiction I’ve read, but maybe you can come up with better examples yourself.

But I don’t see whatever young people’s attitude to sex has to do with Poor Things. It is an irrelevant conflation on the part of the Guardian writer clearly done because it is one of their hobby horses. As for actors’ looks, the history of film way before any kind of sex scenes were normal was built on them and always will be because people like looking at attractive people.

I agree that there are some similarities between algorithms and poetry but also music and novels – all these things can be done by a kind of rote by humans or now, a clever machine that has ‘learnt’ this kind of thing from the vast library presented to it by humans.

But of course the human brain does not actually work algorithmically and art of real value to us reflects the human experience.

This was written as a commission (Larkin, 1974) i.e. in your book, hack work:

The trees are coming into leaf

Like something almost being said;

The recent buds relax and spread,

Their greenness is a kind of grief.

I do not believe that if you asked a machine to write a poem about trees, not one given all the poetry in the world which it could shamelessly plagiarise by algorithmic reconfiguration, but one that really was ‘intelligent’ it could come up with that. In other words such a machine does not exist and never could as a machine could never feel grief and could never feel the beauty of trees or understand something almost being said (but not) or even what relaxation really feels like.

I see what you mean: there’s no ‘mind’ in the machine to which its behaviour (the poem) could be could be reduced as an expression.

But there’s no reason in principle why subjectivity (‘I’ the author of poems and other forms of expression) could not evolve in complex machines in the same way that it has in complex organisms.

Alternatively, perhaps the Cartesian subject has been ‘overcome’ in history (and perhaps partly in consequence of the development of AI, which makes that concept metaphysically redundant and therefore superfluous) and the author is now dead. Perhaps, in our post-Cartesian culture, poems and other phenomena are no longer ‘expressions’ of some ‘ghost in the machine’ but are now just ‘soulless’ machine behaviours, like the ticking of a clock or the beating of a heart or the patter of rain on a forest canopy or the iridescence of a crow’s wing, all of which are in their own way ‘beautiful’.

Both these possibilities have been extensively played out poetically in the science fiction to which SD alludes.

Mind you, the second of these alternatives founders on the irreducibility of the immediate ‘felt experience’ of one’s own subjectivity, which one extends by analogy to others in what we call ‘empathy’.

Is it possible to extend by analogy one’s felt experience of subjectivity to machines? After all, we already now extend it outside our species to non-human lifeforms, which, in Descartes’ day, were considered to be nothing more than soulless machines. Maybe, like animals, machines that generate poems might one day soon also be similarly humanised.

It is possible and I see it as the only way a machine could write a poem that linked trees to grief, a connection that has little logical rationale but one peculiar perhaps to Larkin’s doomy worldview. But my impression is that humanisation is at the moment, a pipe dream.

The rest of the short poem explains the grief bit and also includes the brilliant ‘unresting castles thresh’ that also rhymes with the ‘afresh’ ending. I dunno, I think the poem is a work of great merit and don’t understand how it can be reduced to ‘hack work’. And frankly I have no idea why we would want to turn to machine to produce it, even if it could.

Is it that they are born again

And we grow old? No, they die too.

Their yearly trick of looking new

Is written down in rings of grain.

Yet still the unresting castles thresh

In fullgrown thickness every May.

Last year is dead, they seem to say,

Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.

@Niemand, when a poet takes on a commission, this is a form of patronage. Whoever pays the piper, calls the tune, as a general rule.

The poem you have selected does nothing for me. Perhaps you, the reader, are doing most of the work? And an odd choice, given:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trees_(poem)

I have read or heard many naturalists, life scientists, writing or talking of what inspired them, and if I recall correctly, none of the mentioned poetry, but real-life encounters with nature. I did read an article suggesting there was a genetic component, but I doubt the evidence was strong enough.

If a full understanding of Nature requires systems thinking, since Nature is composed of systems, then we might put abilities in an overlapping range from system exploitation up to system building, with system analysis in between. Most poetry seems to me to be in the systems exploitation zone, or hacks. This requires a familiarity of human language and poetic modes, and from existing poetry from which examples much is copied. Systems analysis is a level of ability further up; did Larkin’s poem capture any essential truth about the system of life that is a tree? I think not. Systems building is an even more advanced ability, although when talking about natural systems, scientists tend to build models (such as climate models) or use small-scale 3D slices you can fit into laboratories, like aquariums, part-built and part-acquired. I don’t think poetry has form or usage in system building, and only a little in system analysis (the odd apt comparison, say).

You may, of course, come up with examples of truly exceptional poetry, but consider whether that really is just evidence for the rule.

Postscript: in a slightly weird diversion, considering evidence for human poets lacking kinds of empathy but producing convincingly deceptive poetry (which is actually a real con-artist practice in dating sites, I am told — look up ‘romance scams’), I found a question “Can psychopaths write poetry?” on Quora.com and found that they offered an answer attributed to ChatGPT. Or on a different tack, nothing stops a blind person writing poems about colours, a deaf person writing poems about birdsong, or a poet who has never seen an elephant describing one. Poetry has an extremely low bar of entry (and, I would argue, it shows).

And the Cult of the Poet is surely why Philip Larkin, who seems to have been a really odious human being, had a relatively burnished reputation in his lifetime (that is, like poetry itself, the Cult of the Poet is a lie). Were I to unleash my world-class poetic talents (consider how you would test that claim), I could make some playful connection between the words ‘ode’ and ‘odious’, but to me, poetry is mostly cheap tricks, the fakery of charm, the duping of the lost, the lacking and the emotionally vulnerable.

By your own admission poetry is mostly ‘cheap tricks’ so any appraisal of a poem you might give has little credence if that is your lens (and it also begs the question, what art isn’t cheap tricks in your analysis? – all art relies on contrivances; look at music – it is highly constructed with a knowingness about how to pull the emotional strings by tried and tested formulae). So I stand by the Larkin poem and don’t feel there is any poem I could present that would change your mind. I would merely say that I find ‘unresting castle thresh’ deeply evocative and pleasing. You don’t. So be it.

And poetry is not about understanding nature, or fully understanding anything, like science attempts to but surely that is obvious? It is like saying Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony isn’t an accurate representation or that Monet’s water lilies are not really precise enough to be ‘true’. And by the by, much classical musical work through history is commissioned or made under patronage, does that make it all hack work? Because a hack is ‘a writer or journalist producing dull, unoriginal work’; it is pejorative not simply descriptive.

I don’t know what you reference to the other tree poem is trying to say other than a tree itself is not a poem about a tree and can neither replace the tree or be the same as experiencing an actual tree. True, but one could say that literally about any representation of anything.

As for Larkin, yes he had a quite unpleasant side to his character but that hardly ever surfaces in his poetry and he was not ‘odious’ (I can safely say I have read a lot about him and am fully aware of his bad side in all its aspects; his life was all a bit crap in all honesty and it was mostly his own fault), and it is nowhere near bad enough for me to dismiss his work – I am not into that kind of cancelling.

One of the deeper ironies of this kind of thing is that not only do artists sometimes not live up to their work in their lives, the work can actually directly contradict it! This is not a ‘con’, it is the contradictions of the human condition laid bare (though yes of course it can be a con if it is deliberately done to fool people into thinking the artist is something they are not and don’t want to be – and it is the last bit that matters).

I don’t look to artists for the moral righteousness of their lives. I am not much concerned if they are hypocritical in that respect because I understand that artists sometimes make art that is suggesting what they want to be but are unable to achieve. We all have out limits of course but the I set the bar high, not as low as some like to today, as if human beings can continually live up to the moral standards they demand and almost certainly never achieve themselves either.

As for ‘odious ode’ or , with poetic licence, ‘odious odery’, yes, that is crap, even hack poetry 😉

@Niemand, I can understand your perspective, and quite reasonably you don’t make great claims for poetry. My concern, briefly, is this: Bella’s editorial position appears to include the rather fringe (if that is fair) theory that poetry will play a significant role in gaining Scottish Independence, maybe dealing with our polycrisis, and so on. This was worth examination in depth. Many paths to Independence and solutions to our polycrisis can be pursued in parallel. Poetry may have had some revolutionary role in various lands in times past. However, we’ve had quite a lot of poetry and precious little to show for it. I think the examination has rather exhausted the slim hope that poetry will be any use, especially given the kinds of developments I mention. And rather illustrated how poetry can be a negative, even somewhat dangerous force, the flickering shadows and false exit directions in the Cave.

You really don’t ‘get’ poetry, do you, SD?

The value of a poem like Philip Larkin’s ‘The Trees’ or Kathleen Jamie’s ‘Fianuis’ lies not in its utility but in its beauty.

The poet’s mission, like that of every artist, is to work some material into an artefact that they find aesthetically pleasing. In the case of the poet, this material is language. In pursuit of their mission, the poet (in contrast to the prose writer) attends to all the qualities of language – its shapes, its sounds, its rhythms, the feel of it in their throat, mouth, and nasal passages, its metaphor, its imagery, its evocativeness… the whole of its sensuousness – and not just its capacity to function as a medium through which information can be communicated, which is the prose writer’s primary interest in it.

To criticise poetry for failing to inform or tell the truth or to be useful for some purpose other than itself is to miss its whole point, which is to create linguistic artefacts that are, like the works of music, painting, theatre, film, or any other artform, sensually pleasing.

One of the problems with the way we see all art is this conflict between the idea that art can be some kind of activist aid, furthering some cause or other, and that which is there primarily for its aesthetics, to generate pleasure as was nicely outlined above. Both forms have probably always existed and they are not mutually exclusive. But I am in the latter camp mostly and get frustrated with the idea that art must be making some kind of conscious point to be taken seriously, and at the very least, even if the artwork is seen as primarily a ‘vehicle’ then it still must still be formally ‘good’ to have real value as art. Part of the problem is that arts funding now demands a rationale and a mostly aesthetic one just won’t do.

There was an interview I saw with Robert Wyatt on a documentary about Rough Trade Records (and the whole argument about ‘selling out’ and privileging attacking the system from the outside) where he simply said he could not see how any pop song could really make any difference to the problems of the world, bring down capitalism etc and to indulge in the hubris that you think it could was stupid. It is hard to argue with that. At best such an approach helps to bolster the committed, rally the troops perhaps, offer comfort to the oppressed but does not have a serious material effect on the problem itself. Even the raising of awareness can feel like dead end because who is listening?

So I agree about not making grand claims for art in a political sense, poetry included. Bella is essentially a political site so inevitably its arts coverage is oriented to politically motivated art but how much that coverage really thinks it can help with the causes that underlie the art varies with the writer it seems to me.

@Niemand, I think you miss out quite a few reasons for making art (including poetry) aside from activism and aesthetics, including commercial (including behaviour modification, such as all adverts), state and corporate propaganda, therapeutic, self-promotion, training, patronage puffs (or public relations) etc.

Perhaps Bella will produce some articles on AI-generated poetry or other artworks, and what the implications are in its primary sphere of interest.

In the meantime, I went to:

https://deepai.org/chat/poet

and input the sequence of words:

Tree Branch Bud Leaf

and the poem it rendered was this:

Tree sways, with leaves and branches

Dancing to the rhythm of the wind’s advances

Buds that bloom and blossom in time

Nature weaving its own rhyme

A world of green, a world of life

A world of bliss, devoid of strife

Every leaf on a tree tells of a story

A testament to nature’s glory

Roots deep within the earth

A foundation of life, a symbol of worth

A tree stands tall and proud

Nature’s expression, never too loud

Each tree, a masterpiece of art

A work of god, a heavenly part

A sanctuary for creatures that roam

The heart of a forest, nature’s home.

But there’s no poetry in that verse, SD. It’s the worst kind of doggerel: unintended doggerel.

That said, it is indistinguishable from some of the unintended doggerel that some human versifiers publish as ‘poetry’.

…and, outside of aesthetics, there is no art. To whatever end a work is put in the service of, whether it’s political, commercial, informational, therapeutic, educational, self-promotional, patriotic, or whatever, unless it’s sensuous (‘relating to or affecting the senses rather than the intellect’), it’s not art.

The AI poem is one long cliché and entirely unoriginal summed up by ‘A tree stands tall and proud’ or ‘A testament to nature’s glory’. It is actually a good example of how bad AI can be: ‘Tree sways, with leaves and branches’. You don’t say. ‘Dancing to the rhythm of the wind’s advances’ is the only line that has any merit. The poem describes but with no feeling for anything. It is funny how with all these text generators when asked to ‘create’ something, prose included, their efforts are so banal, stating the obvious, offering no insight via endless banal regurgitation.

There is indeed a cross-over of that sort of thing with what humans sometimes do as well. But normally, we would have little truck with them. But we get excited when a machine can do it. I can see why as it is clever and new, but what it actually produces is artistically, almost worthless. The best I can say is that it can offer up ideas for development (like ‘Dancing to the rhythm of the wind’s advances’, perhaps) and algorithmic aids have been doing this for decades already.

You are right SD that art has many functions and pure art doesn’t really exist. But AI could produce pure art endlessly by someone simply pressing ‘go’: it has zero motivation and no conception of functionality or aesthetics because it has no conception of anything. But that is why we don’t want pure art and it is impossible for humans to make anyway.

@Niemand, I think you are missing my point; I am *not* excited by the AI-produced poem. It has presumably been trained in a particular way, with some similarity to which human poets are, by reading and regurgitating previous works. And human poetry is rife with cliché, or if you prefer, intertextuality. If Picasso is correct that great artists steal, then machine-learning AI may not be excluded from the category of great artist on that score. And if a poet with writer’s block dips into that current…

But consider more carefully what happens if an AI is trained on poems *you* like. This may be done without your consent, perhaps from stealing your Internet history. Then perhaps generating some poetry that arrives unattributed (or attributed to some human-sounding author) in your feed. You don’t like the first four or five examples, but the next one seems passable, and these results are fed back into the learning loop. Eventually it produces a poem that you rate five stars.

Now, the Poet’s Union we seem to encounter on Bella does not preclude poets having a go at each other, perhaps this was more common in the past, accusations of being a ‘poetaster’, or parodies of classic or contemporary poets (Shakespeare does a lot of this in the plays). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poetaster

But every famous poet who somebody else thinks produces bad verse has had a following. Trying to claim there is a mystical difference between good and bad poetry is likely to run foul of the ‘no true Scotsman’ fallacy. At some point you should accept there is a large degree of subjectivity, and no guarantee that any poetry demonstrates ‘insight’ (unless you can reflect with confidence on your own works).

The really interesting thing is that Artificial Intelligence may have non-human insight, and see patterns that humans cannot (because of scale, say), and maybe capable of producing poetry that other AIs can appreciate but humans cannot. Maybe their favourite form of poetry for an instant of time will be parodies of human works, and their silent silicon sniggering will be at our expense…

(logic silicon parody human poetry)

Logic reigns, a king in circuits,

Silicon veins, a world of circuits,

Parody of man, a machine’s fate,

Humanity’s song sung in binary state.

But where is the heart, that breaks and mends?

Where is the soul, that loves and transcends?

The logic may guide, but emotion understands,

For even machines must bow to life’s demands.

So let us not forget, amidst AI and code,

That humanity’s strength lies in love’s abode,

Let us cherish the hearts, that beat with feeling,

For in them, the power of life is revealing.

I know writers who use AI to generate ‘lumps’ of language, which raw material they then work up into poetry through a process of creative editing.

The process is akin to that of working a poem up from the banal field-notes a writer makes in their journal. It’s also akin to the somatic process of the Romantic poets, who used their subconscious as a kind of AI to generate the raw material or ‘inspiration’ they then worked up into poems like Coleridge’s ‘Kubla Khan’. Indeed, some critics have read Coleridge’s poem as a prolonged metaphor for this process of creative editing itself; although, from the point of view of the poem’s value qua poetry, this (the poem’s possible ‘meaning’) is beside the point.

I think AI has a useful function in creative writing as a tool that writers can use, like the Romantics’ ‘somatic inspiration’, to generate raw material they can then work up through creative editing into exquisite (‘beautiful’ or ‘deeply felt’) linguistic artefacts.

Here’s a linguistic artefact I’ve quickly worked-up from the raw material SD found through his AI app:

The tree sways.

The wind’s whispered advances

flutter its leaves and stir its branches,

which groan in response,

its buds swelling with the promise of blossom.

It digs its roots deep, into the soil,

as deep as your fingers in my hair,

your tongue in my mouth,

the groan in my throat.

@SD

Intertextuality isn’t cliché. Intertexuality shapes a text’s meaning either intentionally, by the use of compositional strategies on the part of its maker, or accidentally, by the chance interconnections that its audience or reader make between it and other texts. One of the questions that used to exercise me when I was doing graduate work in hermeneutics (the theory of reading) at Edinburgh/Hagen back in the ’80s was whether intertextuality can indeed be intentional or ‘authored’ or whether it’s always accidental or ‘authorless’. One thing is certain, though: intertextuality isn’t something either machines or humans ‘do’; it’s a feature of texts themselves, part of the nature of a text qua text.

Cliché, on the other hand, is something that both machines and humans do ‘do’; it’s the overuse of a phrase or opinion to the point that it loses its original effect or meaning.

Picasso et al were correct in saying that great artists steal insofar as they appropriate elements of others’ work from the canon and incorporate it into their own works. These stolen elements usually pertain to the craft element of the canonical artist’s work (the tools and techniques they use in the working of their material) rather than to the content of that work itself; though a previous artist’s work can become the material that the present artist works. For example, modernist writers like Eliot, Joyce, and MacDiarmid were forever reworking Homer’s Odyssey. Picasso et al considered creativity to consist in the innovative use of the tools and techniques they stole from previous artists and in the radical reworking of works stolen from the canon.

I suppose that, from Picassoan point of view, the issue of AI’s creativity or otherwise resolves into the question of whether machines are or can ever in principle be innovative in the way that the Picassos, Eliots, Joyces, and MacDiarmids of the world are.

I think there’s not doubt that AI can produce ‘pulp’ or derivative content (e.g. for genre fiction markets). But there’s no art in that. Could AI make innovative use of the tools and techniques in which it’s ‘trained’ or must it merely replicate their ‘given’ functions? Is AI capable of radically reworking canonical work it consumes or can it only remix it? I think the jury’s still out on that question.

SD: ‘It has presumably been trained in a particular way, with some similarity to which human poets are, by reading and regurgitating previous works.’

The key bit there is ‘some similarity’ but how similar? It kind of assumes the human mind works like a huge database of our lifelong experiences that we recall at will, like AI does. But it doesn’t does it? If that were the case all humans would be capable of total recall and we are not by a very long way. Even rare individuals who have incredible powers in this area are very limited compared to a machine which forgets nothing and has the capacity these days to remember virtually everything humans ever made.

I have little doubt that unless you are told, AI could fool anyone that its output was human work (and ironically, only AI could probably tell you). No doubt it will get better and better at that. The AI tree poem above could easily be written by a ‘hack’ poet. But it is still worthless rubbish. But who knows, it may get to the point where an AI poetry engine produces work rated five stars and as long as we know it is AI then so be it. I have my doubts about that though because for me, the really good stuff adds something that is ineffable and individual to the person creating it, based specifically on their life experiences which are in their sum, and by default, unique.

Apologies for quoting Larkin again but in a poem about the sun, ‘Solar’, there is one simple couplet I have never forgotten:

Coined there among

Lonely horizontals

Like The Trees’ ‘Their greenness is a kind of grief’, it is classic Larkin in the emotively downbeat metaphors / descriptions that are far from obvious. Yes you could probably train AI to emulate this but so what? We don’t need to do that because we already have Larkin and we can only train it to write that sort of thing because Larkin already did it. We don’t want or need another Larkin, or any other poet.

This is why I cannot get much interested in AI art generally at the moment. It is very clever and a brilliant copyist but that is all. It does not operate in the realm of intertextuality like humans do. And though I like Barthes’ ideas, he is a polemicist who in his rejection of the Author-god, seems to reject any notion of original authorship:

‘[The writer’s] only power is to mix writings [a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture], to counter the ones with the others, in such a way as never to rest on any one of them’.

This is false because it misses the crucial point that in doing the above, at some point something genuinely novel can emerge as is testified by the numerous artistic innovators, so it is not the author’s ‘only power’. The real power comes when that novelty emerges. It isn’t just regurgitation and novel juxtaposition, it is a sum greater than the whole of its parts.

@ Niemand

Barthes makes several bold but important claims about the relationship between author and text in his essay on ‘The Death of the Author’ that apply equally to both the machine author and the human author. In fact, the ontological status (mechanical, human, or divine) of the Author is irrelevant to what he says.

Very basically, Barthes claims that no text is original and that the meaning of a text can’t be determined simply by looking to the author of that text. Instead, he claims, we as readers are constantly working to create the meaning of whatever text we’re reading.

Writing, he says, is ‘the destruction of every voice’ rather the creation of a voice, which is how we traditionally tend to think of writing. No text is an original creation either; every text is rather a ‘tissue of quotations’, which the writer assembles from their own reading in much the same sense that Picasso et al claims that every artist steals.

A standard criticism of Barthes is that, in saying as much, he’s overplaying his hand. Surely, works of literature, as distinct from more banal writing that produced by machines and hack writers, contain original phrases and figures. But the reply to this criticism is that, while it’s true that, every work of literature, puts together the raw materials through which meaning is created in new ways, the raw materials themselves (the vocabulary and phraseology and figuration and grammar of the text) have to be familiar and therefore not original, otherwise the work could never be understood by its reader. Every text is just ‘borrowings’ from the literary universe or language it inhabits. Even a work as original as Lewis Carroll’s poem ‘Jaberwocky’ is parasitical and derivative in this way.

Even Barthes’ work is unoriginal. T. S. Eliot emphasised the impersonality of the text in his 1919 essay ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, almost half a century earlier, and New Criticism had already argued that the text has meaning in isolation, separately from the author who produced it, and that searching for authorial intention in a work of literature is something of a red herring. Barthes saw himself and other writers not as an Author, conjuring original meaning out of thin air, as it were, but as someone who was historically embedded in a language whose possibilities he was unfolding

‘The Death of the Author’ was a bold and influential statement, but its argument had numerous precursors: his emphasis on impersonality, for instance, had already been made almost half a century earlier by although Eliot still believed in the poet as an important source of the written text.

In ‘The Death of the Author’, Bathes makes a decent case for considering the meaning of a text to be a product of its relation to its readers rather than of its relation to its writer qua Author. Dickens doesn’t mean the same to us twenty-first-century readers of Little Dorrit as it did to the Victorians who read his work or to Dickens himself. A text like Little Dorrit changes its meaning over time, as its readers change and its language takes on new resonances.

My criticism of Barthes is twofold. First, it needn’t be an ‘either/or’ and that the birth of the Reader in the 20th century doesn’t necessarily entail the death of the Author. We can read Keats’s poems as autobiography and try to understand what the poet himself understood by his words, while at the same time acknowledging that ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ has new resonances for us as Readers two centuries after it was written.

My second criticism is close to your own: that viewing a work of literature as a mere ‘tissue of signs’ threatens to degrade it to same level as a bus timetable or a telephone directory. They, too, put together the same unoriginal raw materials to generate new meanings, but we like to think that ‘art’ is more than this. My argument would be tht the difference between a bus timetable and Keat’s ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ is that, unlike a bus timetable, Keat’s poem is beautiful, and that it’s a great poem because it’s exquisitely beautiful.

This doesn’t, however, preclude the *possibility* of AI producing great poetry. If Barthes and I are right and poetry consists in making linguistic artefacts that we find aesthetically pleasing, then there is nothing in principle that would excludes the possibility of a machine sorting through the raw material of signs and the rules that govern their meaningful combination (which, like Borges’s Library of Babel or his Book of Sand) is infinite and producing by accident, rather than Authorial intention, linguistic artefacts that we as Readers find aesthetically pleasing; that is, ‘poetry’.

A serious, intelligent and confidence-building Scottish quarterly review, how we need one. Surely it’s possible. The LRB was co-founded by a Scot, is presently co-edited by a Scot – but it’s buoyed up by a vast amount of private money.

I think the cultural failure of confidence extends way beyond film adaptation. My sphere is poetry and despite SleepingDog’s opinions we have had some brilliant 20thCentury poets, none of whom have been credited even with a biography. Exception is Alan Bold’s bio of Hugh MacDairmid – 40 years ago. Indeed the Irish grass is greener.

Sure Lanthimos has every right to interpret the work any way he likes and the work is not ‘about’ Glasgow, but, as the second city of the British Empire and the leading centre of production of its steamships and locomotives, it has a strong claim to be the world’s first and foremost steampunk city. An opportunity has been missed.