Union in Education

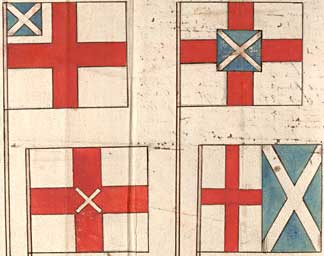

At first there’s much to admire about David Olusoga’s ideas for schools in the UK need to teach the history of all four nations (‘UK schools should teach all four nations’ histories‘). The British-Nigerian historian – who’s new series started on BBC 2 this week – has warned that ambivalence and indifference risk pulling apart the union.

Speaking before the launch of his new documentary exploring the past, present and future of the union, Olusoga said: “We underestimate the complexity and potential fragility of the UK, especially in England.”

“When you talk about the union in Scotland, everyone knows what you mean. When you use the word union in England you realise it’s not a phrase you hear very often. I think we are in England less familiar with the architecture of the country and the history that explains it. That’s why I really advocate better teaching of this.”

At face value this seems like a good idea. Who’s for ignorance?

“Bound by centuries of history David Olusoga explores the union and disunion of the United Kingdom.” You can watch the first episode here.

But in the aftermath of the festival of the grotesque in Manchester, how are you to assess such aspirations to benevolent co-operation? In a series of bizarre interventions Rishi Sunak announces “We’re creating a new, combined single qualification. The Advanced British Standard brings together the very best of A levels and T levels. This is a long-term reform that will take time to get right and extra funding to deliver. No child will be left behind, here’s how”.

Apart from the obvious fact that children are ‘being left behind’ because of disastrous social policy, austerity and privatisation causing endemic poverty … the problem with this announcement is that it doesn’t apply to three out of the four nations involved in the entity still referred to a the United Kingdom.

Education is devolved in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

If even the Prime Minister doesn’t know that, then perhaps David Olusoga’s plans are landing on stony ground? How can you have mutual exchange and common and cross education when one entity has such profound ignorance that it defies the laws of geography? What does anyone south of Carlisle know of our differing educational philosophies?

How can you have cross-cultural education when the casual disdain and ignorance exhibited by the Prime Minister is mirrored by the open contempt towards Scotland routinely displayed by cabinet ministers such as Penny Mordaunt. The Scottish Education system and schooling system requires (imho) a massive, systemic overhaul and transformation. What it does not need is incorporation into the Conservatives latest expression of anglo-normative policy fantasies.

Whatever your method of teaching the most important thing surely is the CONTENT and what you omit or pass over. I watched number 3 of his Union and was very moved by his ancestor returning from the Napoleonic war to poverty, and the treatment of the famine in Ireland – a massive subject. But he seems to have breezily passed over the Highland Clearances even though I’d have thought there was some materials straight up his street about the relationship between ownership of slave and the laundering of money in buying Highland estates and exploitation of the people who lived there. McKinnon and Mackillop’s work is essentially to begin to understand what was going on.

There was more, still have to watch the final episode. But I thought that the assumption that everyone in the UK shared the same attitude towards the French (the auld alliance got no mention) could have a bearing on future speculation about Brexit and the health of the present regime.

No, Cathie; the most important thing in teaching history (or any of the ‘humanities’ or hermeneutic sciences) are the critical skills that the student acquires from their studying. What they study isn’t nearly as important as the abilities they cultivate in studying it.

As you may remember from other stuff I’ve ‘mansplained’ here (though probably not), I’m a great fan of the liberation pedagogy of the Brazilian educationalist, Paulo Freire, who was critical of the traditional ‘banking’ model of education. For Freire, education shouldn’t be about teachers ‘colonising’ or depositing information into their students’ otherwise empty minds; it should be about equipping those students with the hermeneutic (interpretative and evaluative) skills that will enable them to cultivate their own knowledge. Freire characterised the banking model as the ‘pedagogy of the oppressor’ and his own educational approach, by contrast, as ‘the pedagogy of the oppressed’. Freire has since become a key figure in the theory and practice of decolonisation.

Whether students study the Highland clearances or not is really neither here nor there; what matters is that, whatever they study, they could then go on to apply the study skills they develop to whatever matter they themselves choose to explore.

My own children (who went on to study Music, Geopolitics, and History respectively at university) benefited from having excellent teachers in our local state school who employed a Freirean approach in their pedagogical practice, and they’ve as a result matured into successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens, and effective contributors to the civic lives of their real and imagined communities. None of them, as far as I know, knows much about the Highland Clearances; they’re not something that particularly interests any of them.

What an arrogant response ! I will not reply in kind but am disappointed that people should not seek to know more about the entrenched inequalities in the society they inhabit. I look forward to a more informed discussion when I’ve watched the last episode. Olosega is bold to have attempted this mammoth task, but I wonder as the next comment suggests, which BBC monitors were looking over his shoulder.

I appreciate your disappointment, Cathie; but I’d still arrogantly maintain that Freire’s ‘pedagogy of the oppressed’ equips people with the skills they require to not only investigate the entrenched inequalities in the society they inhabit, but also to effectively challenge and liberate themselves from those inequalities. I’m not sure that watching a piece of BBC entertainment or colonising minds with the ‘right’ content does that.

We may have read and benefited from Freire but are you seriously suggesting that people here somehow absorb his ideas without any exposure?

So your and your children’s minds have been colonised by Freires ideology. Whose going to de-colonise us from his thoughts.

Give me the Scottish Enlighment!

No, Cathie; I’m not suggesting that at all.

@ John. My mind has indeed been colonised by critical theory; it’s also been colonised by the schools of analytic philosophy, and phenomenology. I shift between their respective thinking strategies, depending on which I find the most useful when thinking through a particular problem, and also to cast the same problem in different cognitive perspectives. This eclecticism is particularly helpful when I’m thinking through the problems around reflexivity (e.g. how one can overcome the prejudices that colonise one’s mind when that overcoming must itself be led by those very from those very same prejudices that exercise their hegemony over one’s thinking).

And, yes; Freire’s ideology is, like all ideologies, something to be surpassed, even as it’s historically shaped both my thinking and my children’s education. That’s part of the aforementioned problem of reflexivity: no thinking or practice ever takes place ‘objectively’, outside the context of some thinking strategy; all thinking is embedded in some praxis.

So, you’re right: Freire’s liberation pedagogy must itself be subjected to the sort of criticism that it equips students to carry out; otherwise, it too would become oppressive.

Accept nothing; question everything! That’s how you liberate yourself from mental slavery (as Bob Marley sang) and grow.

Where are you from?

Physically, I live in the South[ern Up]lands. Digitally, I’m nowhere and everywhere.

This sounds to me like a false dichotomy. It brings to mind an anecdote of Eric Hobsbawm about teaching at the New School in New York. After delivering a lecture, a student came up and enquired: You mentioned the SECOND world war. Does that mean there was another one before it?

So, is this proof of the success of the American education system, the student having correctly applied their critical skills to interpret the word ‘second’? Or complete failure in not communicating basic facts?

Eric Hobsbawm’s anecdote illustrates that the student successfully applied their own critical faculties to identify a need for further research and to pursue that research by asking Hobsbawm to supply the requisite information. I’d hope that the student wouldn’t have then just taken Hobsbawm’s answer on trust, but would have subsequently sought out further evidence to corroborate that answer. Teaching students to do this, to learn in this way, actively and self-directedly, rather than by passively absorbing whatever information some authority feeds them at its face value, is liberation pedagogy, the ‘pedagogy of the oppressed’.

(Which dichotomy do you find false, BTW?)

The ability to critically appraise what you are studying is a basic skill that all students require to be taught. For example in my specialty in science the ability to review a medical paper needs one to look at how study has been set up, number of participants and how results have been analysed.

To say that the only important thing students learn from any subject is entirely inappropriate.

Your comments about your children not requiring to know anything about a significant historical event in the country they are being taught in will lead them to not having a full awareness of that country.

Having read that you appear to slavishly adherence to one methodology of teaching is in my experience the very opposite of applying critical thinking and this comes through in the arrogance of your comments, an arrogance that is very common to people who are convinced of their own personal beliefs.

But I didn’t say that the critical thinking skills or disciplines that students learn in the humanities are the ONLY important thing students learn from studying those disciplines; I said they were the MOST important thing they can learn for the sake of their of their personal growth or development as successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens, and effective contributors to the civic lives of their real and imagined communities. Those excellencies are what liberation pedagogy would have teachers teach.

As successful, independent learners, my children are perfectly capable of learning about the Highland Clearances if they ever have a notion or feel any need to.

To understand the country you live in you need an appreciation of history which forms the society and opinions of today.

This history should be taught in an informative manner free from xenophobia with critical appraisal and open to debate.

The highlands of Scotland are a significant part of Scotland (& the UK). The economic and social fabric of the highlands today are still in part informed by the history of the highlands in particular the highland clearances.

If you are a historian living in Scotland and you deny this reality you are being wilfully ignorant of the importance of history in relation to a country- in this case both Scotland and the UK.

I should add I have no religious beliefs and neither do my children but I would consider it necessary to have a background knowledge and understanding (not indoctrination) of the major religions creeds in Scotland to understand society today.

To fail to do so is failing to prepare our children for the society they will grow up in.

@John, yes indeed. That is rather the point of national curriculums, which can be of varying quality and intent.

There is a disturbing documentary on BBC iPlayer showing what can happen when children are *not* taught about who once lived on their land, and what was done to them:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m001q7qz/storyville-blue-box?page=1

How can children decide for themselves what parts of history they should and should not learn from a position of ignorance of history? While vacuums can be the most dangerous parts of minds to fill (as the Naomi Klein in conversation with Gemma Milne on Bella highlighted): there is nothing there to integrate (and possibly challenge) incoming mis/dis/information. This is also why it is highly dangerous for parents to lie to their children (Santa Claus, God, parental infallibility etc). I think even poets have made that connection (tangled webs and all).

I agree, John; with to reservations;

Firstly, a learner might not be interested in understanding their country. In a democratic society, we should respect their autonomy as a learner and concede their right not to be interested in the stuff we think they should be interested in.

Secondly, in our multicultural society, the history that forms the society and culture of Scotland today is World History. My youngest son is currently serving his time as a historian, and he has chosen to study the events that have shaped the historical experience of the so-called ‘New Scots’ rather than the diet of events prescribed by the 19th Edinburgh Tories, who practically invented the traditional historiography of the parish. Again, in a democratic society, the experience of so-called ‘native’ learners shouldn’t be privileged over the experience of ‘naturalised’ Scots.

I’m sure we’ve discussed this before, SD, but the point of Scotland’s National Curriculum for Excellence isn’t to fill our children’s heads with approved content, but to cultivate in them the skills and qualities (the ‘excellencies’ referred to in the title) they require to become successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens, and effective contributors to the civic lives of their real and imagined communities. Like I said above, Freire’s liberation pedagogy has been tremendously influential; it’s even revolutionised Scottish education over the past 13 years or so. Did you visit Scotland’s CfE website like I suggested?

And of course children can decide for themselves what parts of history they want to learn. Why would you deny them this autonomy? Are you afraid they might not learn what you would consider the ‘right’ bits?

I teach at HE level and at that level, critical thinking, research and analysis skills are the most important in subjects like history and the humanities generally. Subject matter at that level, though not divorced from the *idea* of a curriculum, is a vehicle to allow the students to become autonomous learners. This is to allow them to increasingly and effectively explore the subject matter they want to, whilst providing generic skills that employers want and indeed, a successful life demands. But it is wrong to apply the same emphasis to children who, essentially, know very little history of their own land or anywhere else, so go to school to learn about important stuff that has happened. What that curriculum should be is a different question but one that is not beyond the wit of man to devise in a sensible and balanced manner. Along the way they should gain critical thinking skills, absolutely, but the emphasis is reversed compared to HE.

Yep, while Scotland’s CfE aims at developing the same skills and qualities throughout the student’s educational experience, from early years through to university or college or employment, it does have different but interlinked areas of learning (rather than traditional academic ‘subjects’), with each area graduated into levels (Early Years, Year 1, Year 2… etc.), and with each level having its own set of milestones, against which each child’s competencies can be monitored as they progress through the journey of their education.

The old academic division of ‘History’ falls under the area of Social Studies.

From Early Years to Year 4 (roughly the old Nursery and Infant Schools), learning in the area of Social Studies is focused on developing a range of competencies related to ‘investigating’, ‘exploring’, ‘discussing’, and ‘presenting’ by investigating, exploring, discussing, and presenting on other people and their values, in different times, places and circumstances, and about their own social environment and of how it has been shaped.

By the end of Early Years, children are expected to be aware that different types of evidence can help them to find out about the past and to be able to make a personal link to the past by exploring items or images connected with important individuals or special events in their own lives. By the end of Year 4, they’re expected to be able to evaluate conflicting sources of evidence to sustain a line of argument, to have developed a sense of their heritage and identity as a local, Scottish, British, European, and global citizen, and to be able to present arguments about the importance of respecting the heritage and identity of others.

It’s left entirely up to the teacher what content that learning will have, and ideally that should be guided by the interests of the child. The emphasis of the Scottish CfE, from Early Years to Higher Education, is on developing the skills and qualities that children and young people will need to excel as adults, rather than on filling children’s heads with approved knowledge.

I have just completed watching Union with David Olusoga. I found it a bit sketchy (hard to cover so much ground and hundreds of years in four episodes) and the vox pops didn’t add anything like as much as, say, the Once Upon a Time in Iraq testimonies. But I learnt a few important things and the historical evidence was really well handled.

Where Olusoga is wrong, I think, is in claiming the British Empire is over, and his greatest weakness was sticking to a repeated model of UK = Union of England + Wales + Ireland + Scotland, when the geopolitical reality has always been more complex, much larger, much more unequal, more contested, more secretive, and more poorly taught. My support for Scottish independence is largely based on rejection of still-imperial Anglo-Britain (not a normal modern state by any means). The show addressed cultural and economic pros and cons of Union, but largely gave politics beyond class, religion and inequality (extraordinary concentration of power and riches in London was highlighted) a miss. Environmental degradation was hinted at in the devastation of Ravenscraig, but unexamined.

Still, the show functioned as a quick run-through and no doubt viewers will find more at the Open University and from further learning opportunities. There were some fairly big gaps (I don’t think the British quasi-Constitution was really addressed, or the way large segments of British policy remain outside of democratic influence or parliamentary oversight), cultural production was largely ignored, as was the influence of foreign powers (like the USA after WW2) and international organisations (the EU was briefly mentioned). Invasion of Britain featured frequently as a fear, but not in relation to the frequent invading that Britain had been doing. The neocolonial side of financialisation including tax havens, the Royal prerogatives (including war and secret services), British diplomacy and arms trading, all deserve a look in understanding what the Union (actually still the British Empire) *does* in the world. And how it restricts access to historians.

Still, I expect Olusoga or his BBC minders were treading carefully.

I’ve just checked out the Open University site that accompanies Union with David Olusoga, and among the six audio stories is a short description (it would be helpful to know beforehand how short, OU) of the Scottish Radical Wars:

https://connect.open.ac.uk/society-psychology-and-criminology/union-with-david-olusoga

The term ” four nations” is used repeatedly in discussing these programmes. The UK doesn’t consist of four nations. The people of Northern Ireland are part of a nation, not a nation as such.

A surprising inaccuracy.

I’d disagree with you there, Margaret. The people of Northern Ireland participate in a civic life that’s quite distinct from that in which the people who live in Southern Ireland participate, which is what makes them distinct ‘nations’.

I suspect you’re coming from the old and largely discredited theory that makes nationality dependent on ethnicity rather than on civic participation. In the postmodern world of multi-ethnic/multicultural communities, the old theory no longer works and has become positively dangerous.

Ah, you’re one of these omnipresent people, who is always happy to be vaguely insulting.

I don’t care if you object to me or not. What about the salient point I made about the nationality of the people in Northern Ireland? Is it a function of their civic participation or a function of their ethnicity? And, if it’s the latter, what is the status of all those Northern Irish citizens who aren’t ethnically ‘pure’? Do they not count?

@Margaret Brogan, yes, that is a common, mainstream and official usage, for example in the Ireland National Rugby Union team that competes in the Six Nations (was Five Nations before Italy joined) tournament, I think, and applies to the men’s and women’s teams.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ireland_national_rugby_union_team

Aye, the Irish Rugby Union’s a bit of an anachronism. It was formed as a single national union in the 1870s from an amalgamation two smaller unions: one made up of clubs based in the south of Ireland (centred around Dublin) and another made up of clubs based in the north (centred around Belfast). This national union chose to ignore the partition of the island into two separate nations in 1921, and continued as an all-Ireland union.

The ‘Home Nations Championship’ became the ‘Five Nations Championship’ when the French Rugby Federation joined the competition in 1910.

Anyhow, the all-Ireland nature of the IRU hardly reflects the current geopolitical situation with regard to the island and the nationalities of the people who live there.

@Margaret Brogan, and on further investigation, this official UK government definition:

“10.2 Definitions

10.2.1 United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (usually shortened to United Kingdom)

The United Kingdom is a constitutional monarchy consisting of 4 constituent parts:

3 countries: England, Scotland and Wales[footnote 23]

1 province: Northern Ireland.”

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/toponymic-guidelines/toponymic-guidelines-for-map-and-other-editors-united-kingdom-of-great-britain-and-northern-ireland–2

chimes with the original ‘temporary’ partition and the use of the provincial name ‘Ulster’ since (Royal Ulster Constabulary, BBC Radio Ulster etc).

Union with David Olusoga covered a period where the whole of Ireland was in the UK, and that is why I dropped ‘Northern’ from my earlier comment, although on reflection I should have put it in brackets. I really meant to call attention to territories outside these designations (which extend from islands around Britain to far-flung places around the world.

I inadvertently heard the announcement by the English PM and was not surprised that he was ignorant of both the geography, both physical and political of their so-called United Kingdom.

English Exceptionalism and English Nationalism as always.

He’s not the English PM, Colin; he’s the British PM. England doesn’t have a PM (or any devolved government, for that matter).

He and his party of reptiles have no mandate in Scotland.

His obvious ignorance of the independent education systems merely exposes his Anglo-centric thinking.

Of course he doesn’t have a mandate in Scotland, Colin, any more or less that Humza has a mandate in Dumgall or in the South[ern Up]lands more generally; as the duly elected PM of the UK, his mandate is UK-wide, just as Humza’s is Scotland-wide as the duly elected FM of Scotland.

But, yes; whoever named the proposed new ‘Advanced British Standard’ committed a solecism that we can use to stoke our grudge and grievance against the Auld Enemy.

Just a reminder of Sunak’s thinking Mike –

https://nation.cymru/news/british-can-be-used-as-shorthand-for-english-suggests-rishi-sunak/#:~:text=The%20Prime%20Minister%20has%20suggested%20that%20the%20word,they%E2%80%99re%20devolved%20to%20Wales%2C%20Scotland%20and%20Northern%20Ireland.

Hello 230905 I am not educated to a high standard. Half the time on here I don’t know the references made to people who have obviously been important philosophers and the like, but I still think, so I have to disagree with you on your main point. If I wanted to find out about say Scottish history I would want content on actual events that occurred – that’s what I would be paying for. Same if I enrolled in say a course in Spanish I would want to actually have content that would use Spanish in it, same with physics etc. If I wanted to gain the critical skills you mention – these ‘hermeneutic skills’ I would enrol in a course on learning those skills – say, ‘hermeneutic skills for dummies’. I don’t know about this Freyer bloke but I feel he has a fundamental error in his thinking for he suggests in his liberation theory stuff that people like me, the ‘not so well educated’ do not learn those “hermeneutic (interpretative and evaluative) skills that will enable them to cultivate their own knowledge” – well we do. Life teaches you those skills not just study. If you accept my position then what he posits is worthless, better to stick with content. If you accept his theory, then all of us ill-educated folk are dummies. Is that what Freyer was saying? Or is it just that the educated sometimes over think the obvious, that as human beings we all learn the same stuff from a variety of stimuli presented to us simply by the act of living? Some things are simple, humans learn human things. The content I obviously lack is who the Brazilian educationalist, Paulo Freire is and what his relevance is and if I wanted to I would find a course that told me, not one that told me how I might find out.

Freire’s idea was we do indeed learn by experience and that this kind of learning is better than learning by instruction. This is generally accepted in education nowadays, where the teacher’s role is more that of facilitating those learning experiences than that of filling empty heads, but it was a pretty revolutionary idea in Freire’s time. As I said above, It very much informs Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence, which the Scottish government introduced in 2010.

I first came across Freire’s work in Gorgie-Dalry, just before I began by philosophical apprenticeship, where the Adult Learning Project, based on Freire’s work, was established in 1977. Among its aims, the project sought to provide affordable and relevant local learning opportunities and to build a network of local tutors (of which I was one through my trade union activity with the TGWU). Approximately 200 people participated in this project in its first years. A similar project was established in Easterhouse as part of the grassroots initiative to build a so-called ‘popular education movement’ in Scotland. Via these kinds of projects and the work of organisations like the Workers Educational Project, Freire’s philosophy came to inform much of community education in Scotland, which, of course, died a ‘death of a thousand cuts’ in subsequent decades.

Working in the early 1960s with marginalised groups in north-eastern Brazil, Freire concluded that there could be no such thing as politically neutral education; traditional education promoted the values of the dominant classes, ignored the real-life knowledge and experience of the ‘oppressed’, and maintained a social order in which the oppressed came to blame themselves for their poverty.

He argued for an education which would ‘liberate’ rather than ‘domesticate’, which would enable poor people to understand the structures of oppression and do something about them, a process unhelpfully translated as ‘conscientisation’. The oppressed themselves – not revolutionary vanguards – must be the principal agents of change, and education should contribute towards this collective empowerment.

Freire’s great academic contribution was to have developed a pedagogical methodology for putting these ideas into practice. The teacher’s role, in his scheme of things, isn’t to deposit knowledge into empty minds (what he called the ‘banking’ model education), but to enter into dialogue with learners, respecting what they know of their own reality, but provoking a deeper analysis of that reality.

The teacher thus doesn’t provide answers; instead, they pose problems, ask open-ended questions, and help learners take a step back and look critically at their own everyday experience. Typically, learners would use reminiscence work to analyse photographs that depicted important issues in their lives (e.g. poor housing, unemployment, violence and abuse, for example) and offer and discuss their various interpretations and judgements). Crucially, the teacher would also encourage learners to consider what they might do to bring about change, the action they subsequently took then becoming the focus of their subsequent enquiry.

After I served my time as a philosopher, I returned to my wider inclusion and capacity building work and continued to use Freire’s methodology in the development of local community action groups until I retired 15 years ago.