Insatiable Curiosity: The Real Politics of Poor Things

The film Poor Things, directed by Yorgos Lanthimos, from Alasdair Gray’s fantastical (1992) gothic novel is a triumph, a visual feast featuring superb performances by Emma Stone and Mark Ruffalo in particular. Contrary to expectation I didn’t find myself grinding my teeth in despair at the lack of Glasgow, Scotland or Gray’s original story. Instead, as Bella herself says : “I am finding being alive fascinating.”

Can someone please explain to me why this film is so damn brilliant?! #PoorThings #cinephile #Cinema #emmastone #yorgoslanthimos pic.twitter.com/LqMi61HcHy

— Balthazar D. (@a_dannaoui) February 8, 2024

The design, costume, make-up and cinematography are extraordinary and offset by the beautifully quirky music score by Jerskin Fendrix, who as Johnny Rodger says (‘Being Bella Baxter‘) provides “a powerful series of emphatically existential howls, magnifies the uniqueness of Bella’s situation in the world.”

The film contains simultaneously the brutal world of instrumental science and disgusting misogyny, alongside the purity of the search for knowledge and the innocence of Godwin Baxter’s creation: Bella.

But no critics that I’ve seen, or read, have taken any notice of the book and film’s political underpinning, other than to debate the gender issues involved.

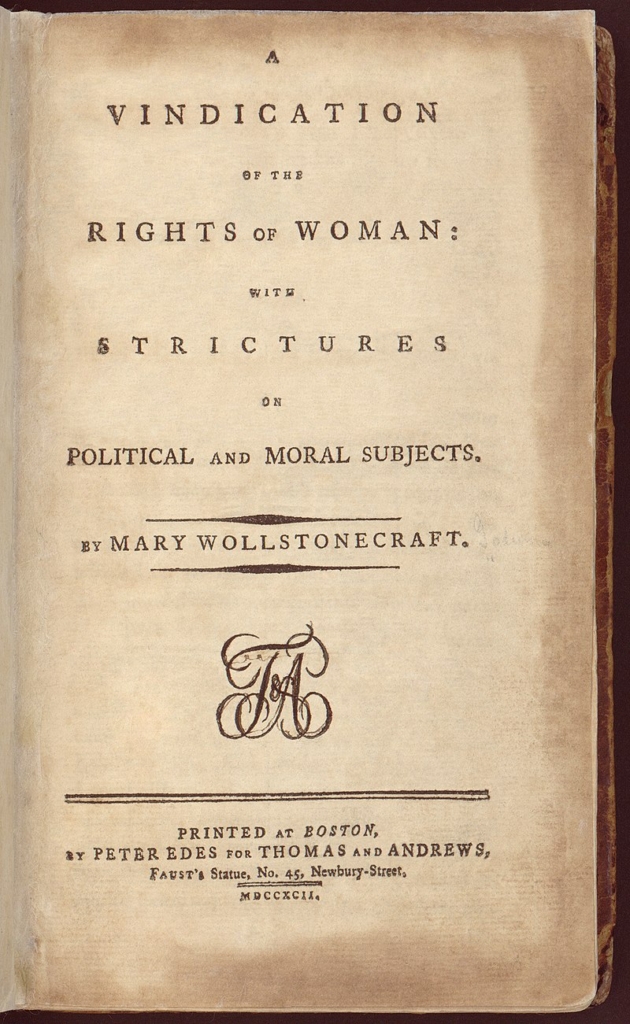

In Gray’s book, he draws on and plays with, 19th literary and anarchist political history to create the novel’s backstory. It’s quite clear: William Godwin was the father of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, author of Frankenstein, of the Modern Prometheus (1818), wife (and editor) of the Romantic poet and philosopher Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Mary’s mother (Mary Wollstonecraft) died eleven days after giving birth. Her surviving daughter was raised by her father William Godwin, who home-educated her, encouraging her to adhere to his own anarchist political theories.

This is the novel’s inspiration – and its one of the threads that follows from book to film in content and form: it is anarchic and transgressive. It’s to Yorgos Lanthimos’s great credit that this politics is retained, if ignored by most (all?) of the film critics.

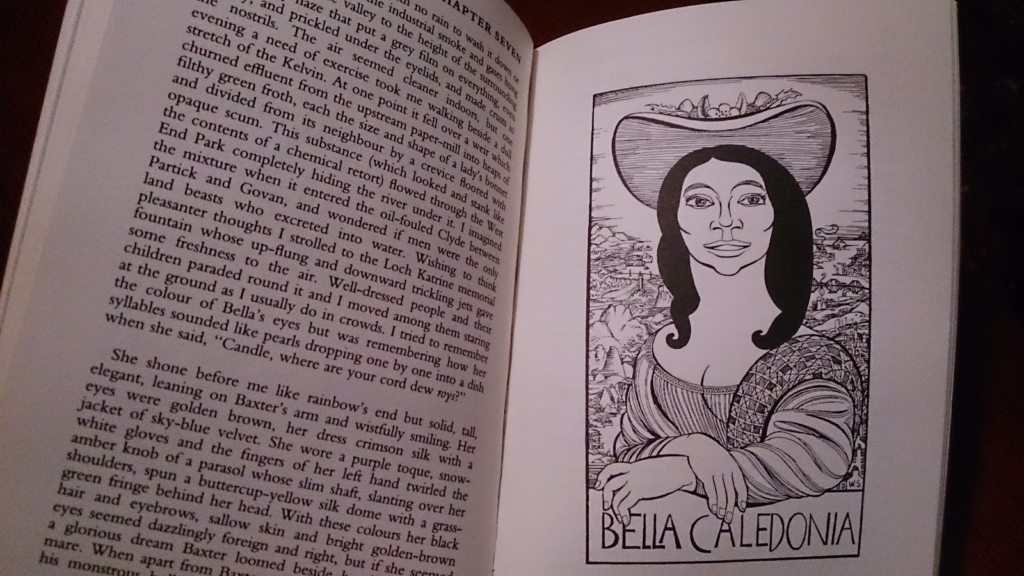

William Godwin

This review is not just geekery (though doubtless it is that). As I explained a couple of years ago about the origin-story of the magazine you are currently reading: “Bella Caledonia emerged from the pages of Alasdair Gray’s novel Poor Things in 2007. Since then we have strived for autonomy, independence and self-determination, and to “work as if you are in the early days of a better nation.” In my imagination Bella was looking for a publication and an alternative media and a political movement that was innocent, vigorous and insatiably curious.”

Bella Baxter’s film incarnation manifested by Emma Stone, in surely an Oscar-winning performance this ‘insatiable curiosity’ is the hallmark of her character and the story. This theme is captured in this still from the film:

And the idea that the film is a complete disjuncture from the book is flawed. Take for example this extract from our editorial statement ‘Bella Caledonia, Poor Things and the Fifth Estate’:

Gray writes: “She shone before me like rainbow’s end but solid, tall, elegant, leaning on Baxter’s arm and wistfully smiling. Her eyes were golden brown, her dress crimson silk with a jacket of sky-blue velvet.” Clearly the visuals of Gray’s masterpiece informed the directors visual as well as his politics.

Bella’s creator (‘God’) Dr Godwin Baxter, played by Willem Dafoe was brilliant as the tragic scientist who himself had been experimented on by his own father and has his own gastric complications. His performance is only undermined by his Scottish accent that seems to hover somewhere between Grampian and Illinois. Sometimes the film is laboured and you want it to hurry up. The attempt to reflect the actual process of awakening for Bella means that there are scenes that lag.

If we take Bella Baxter’s parents as Mary Wollstonecraft author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy, and William Godwin, the godfather of modern anarchism we see a different insight into both the film and the book that inspired it.

As you watch the early scenes of the film unfold you are disoriented by the ‘fish-eye’ distorted perspectives that make you unsure who is the viewer and what lens you should trust. This is an explicit homage to Gray’s own visual legacy, as seen here:

Two things are going on in this appropriately botched film review, like a badly orchestrated surgical exercise. One is to walk back from my previous criticism that the film was undermined by not being set in Glasgow and diverting from the novel’s key themes. The other is to inject a different politics beyond the frothy but superficial gender analysis: “As a work of fiction, Poor Things can explore anything it likes, but it is not feminist” said Samira Ahmed, presenter of Front Row on BBC Radio 4.

But a different read is that it really is not just radically feminist but anarcho-feminist. By stepping out into the work and being ‘insatiably curious’ we can see this in both the film and the books key themes that shine through despite the hype and misdirection of the critical assessment.

The idea to “strive for autonomy, independence and self-determination” is Bella’s, and all of ours.

The film creates a world we cannot conceive of, and that is precisely the challenge we face given the disgusting reality of the one we inhabit “work as if you are in the early days of a better world” as both writer and film-maker might agree.

See also:

Being Bella Baxter by Johnny Rodger

The Poor Things Problem by Mike Small

Alasdair Gray on Poor Things

Work as if you were in the Early Days of a Creative Republic by Christopher Silver

Bella Caledonia, Poor Things and the Fifth Estate

Florence, Paris, London, New York (Glasgow) by Laura Waddell

The Sociology of the National Cringe by Isobel Lyndsay

Culloden via Tesco? by Scott Hames

Poor Things and Bella Caledonia by Kirsten Stirling

Hmmm. I suppose positing ‘man creates woman’ (instead of the other way round) as radical feminism is going to leave some poor women scratching their heads, particularly in the context of a story which sounds like a fan-fiction knock-off (or porn version) of Frankenstein: or, the Modern Prometheus, which was insistently hierarchical (the unequal relationship between Creator and Creation could in no rational sense be anarchic). But I’ll clearly need to read the novel, then view the movie, in order to judge. I don’t know anything about Samira Ahmed, but perhaps she has some credibility?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samira_Ahmed#Equal_pay_tribunal

As for Mary Wollstonecraft, her works are worth reading on their own merits, regardless of how much she is alleged to owe to her father. She wrote that women of her society were educated to be “alluring mistresses than affectionate wives and rational mothers”, advocated rational alternatives, and condemned James Fordyce’s Sermons to Young Women as sexualised angel youth fetish.

Anent feminism in critiques of the film: I have spoken with women who agree that the film is feminist and shows via Bella a woman in control her own sexuality. They also argue that in the various scenes Bella is compassionate and single minded about what she believes to be right and what wrong. She exerts influence over the main male characters in the film and to a fair extent wins them over to her side of the argument. Other feminists to whom I spoke or whom I heard in dialogue with feminists like the ones I spoke to in the opening paragraph tended, in various degrees to the view pronounced by Samira Ahmed.

I think this demonstrates that what feminism comprises is contested.

You state that the film (or novel or both?) sounds like fan fiction. Have you actually seen the film or read the book or both?

For clarification, yes I have read the book and watched the film, which was what the entire feature review was based on. Not only that but the entire premise of the site that you are interacting with is based on the book (!) which has been laid out (probably boringly) for years. Alasdair Gray and I (and Kevin) co-created this project based on the fucking concept. If you want to have a go gave a go with a fucking clue.

Alastair Macdonald’s question – ‘Have you actually seen the film or read the book or both?’ – is directed at SleepingDog, editor, not at you. It’s Sleeping Dog who used the phrase fan fiction.

You have clearly read and watched and thought about Poor Things more than just about anyone. Your account of the relationship between the film and book is the best and most useful I’ve read. Thank you.

Ah, thanks Duncan!

Read the book. Watch the film.

@Editor, I have reread Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) and just finished reading Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things: episodes from the early life of Archibald McCandless MD Scottish Public Health Officer (1992).

Frankenstein creates his Creature as a male, perhaps as a default, perhaps he could have made the Creature sexless, perhaps as the text says Creating Woman was the advanced class so Frankenstein had to get some expert help (in England). If Frankenstein had created a female Creature first, it wouldn’t have changed the story in any significant way I could see. The Creature’s nature was essentially plastic, and physically set apart from humans.

So what if Bell was Bill, a male version? What if Godfrey Baxter had created Bill for the same reason he gives for creating Bell? What would change, if anything, about your take on the novel?

Correction: Godwin Baxter.

The movie was at least true to the novel in being overlong and lined with tedious devices; a bourgeois whimsy of scandalising society and getting away with it/incel fantasy with hints of incest, necrophilia and paedophilia. Stripped of its socialist minilectures (ease of which showing them as mere bolt-ons), the movie extinguished the two tiny sparks of collective action in the novel, replaced the religious character and dampened Wedderburn’s newfound religiosity, and strangely rewrote the ending (keeping the shoddy contrivance of General Blessington as convenient monster but neutering the anti-imperialism). Why choose Alexandria for child beggars when London’ ‘People of the Abyss’ were more conveniently to hand?

The movie’s imagery reminded me of the assistance of AI which we’re likely to be subjected to. I think if the movie had centred on Bella’s experiences, the earliest impressions should have been most vivid, not the dullest. I was a little surprised how dull I found the movie with its lacklustre dialogue, underdeveloped characters and awkward pacing. There was at least some wit in the novel.

Talking of Techbro AI, Bella (and Mk2) is in a long line of quite similar imaginings, from movies like Ex Machina to chatbots like Microsoft’s Tay disaster. We were back in French New Wave territory, though thankfully not quite *that* tedious and pretentious.

Neither novel nor movie can reasonably be described as ‘feminist’, and attempts to explain to actual feminists that this really ‘radical feminism’ is inexcusable gaslighting. The movie is regressive, and some of the plaudits just embarrassing. I think Samira Ahmed’s take is essentially correct.

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2024/jan/24/bound-gagged-poor-things-feminist-masterpiece-male-sex-fantasy-oscar-emma-stone-ruffalo

Thanks Sleeping Dog – I think we disagree on this one

@Editor, seems so, even to the point I now consider the movie’s replacing Glasgow with uninterrogated London to be bad for the same reason as cutting out the other end of Europe. Two nations bullied by a larger neighbour, gone. Europe–Mediterranean shrunk and grossly caricatured.

For the movie’s backers, including Film4, I guess they can now make lots more movies with other kinds of explicit sex and if anyone objects, they’ll say: but you loved Poor Things, you must be some kind of bigot (and have a point). If Poor Things 2 features Bill, this prophecy will be fulfilled.

For all my criticisms of Gray’s novel, I think the movie mutilated it and dumbed it down objectionably. What people who see the movie first then read the novel will make of it, I have no idea. The novel was hardly signposted in the movie, from what I could see.

From the Alasdair Gray Archive project:

“Congratulations to the whole team of @poorthingsfilm for their Oscar wins, especially Emma Stone for her best leading actress award for playing Bella Baxter.

Bella Baxter is the female Frankenstein monster around whom the narrative revolves. Throughout the story she gains her own agency and is able to free herself from the expectations placed on her by the men in her life. Find out more about the original Bella via scanning the QR code or through the link in our bio or visit http://www.poorthingsnovel.com

‘Poor Things: A Novel Guide’ was designed by Rachel Loughran with contributions from over 30 other supporters. These posts have been designed by @gravezink “

The site’s synopsis at least provides a timeline (of Archibald’s account), which I guess confirms that Bella and Wedderburn were in Alexandria shortly after the British bombarded the city in July 1882, causing a great many civilian casualties and general ruination:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bombardment_of_Alexandria

which as a student of British imperial history I was aware of (John Newsinger devotes a chapter to The invasion of Egypt, 1882 in his book The Blood Never Dried: A People’s History of the British Empire, 2nd Edition (2013)), but seems to have escaped the notice of Gray (though the account is fractured and I may have missed something in the novel).

However, the movie most egregiously omits this massive British crime against humanity, the untrustworthy Astley (whose chapter-length monologue on how-the-world-works was obviously too unwieldy for dramatisation) attributing it to heat, a racist way of saying that Egyptians couldn’t adapt to their own climate.

In reality, the British bombardment of Alexandria is ideal for creating what UNICEF calls ‘WCNSFs’. That these desperate children just materialise in the movie without mentioning the perpetrators is exactly the cowardly crime of omission that Western journalism is guilty of in present news reporting when it talks circumspectly of humanitarian crises.

I suspect the reputation of the movie will shortly curdle and tank, if it hasn’t already, except among a particular class of wankers. Movie-Bella is not woke, does not ask the right questions, her choice of career (medicine) is worthy but reactive, and as the novel also suggests, may be in part a result of her various traumas. Novel-Bella *is* woke, but a different kind of woke from Novel-Victoria. Movie-Bella cruelly puts the brain of a goat into General Blessington’s body, suggesting that irrational cruelty is main lesson she’s learnt (contrary to what the novel implies). Movie-Bella rescues herself from Blessington’s house, but in the novel we get a tiny flash of recounted collective action as the servants come together to free Victoria after Blessington’s adultery and cruelty is revealed by a mistress, sparking empathy in Victoria.

Sleeping Dog belies his name as he continually chews at his favourite bone!! Enough,already- nothing left to say,as the Pogues said in song- he even used the ‘Renton’ word in relation to ‘fans’ of both book+film- I suspect he’s either English,a Tory, or both!

@Hugh McShane, I get that some people have an emotional investment, but I don’t see that pointing out the whitewashing of a British Imperial crime against an East-Mediterranean largely Arab-Islamic urban populace is a hallmark of English Tories? These guys might explain the use of language better than me.

https://www.medialens.org/2024/israels-flour-massacre-when-a-crime-becomes-a-tragedy/

@Editor, indeed. I felt obliged to perform some due diligence on the question “Why Does Poor Things the Movie Hide the British Bombardment of Alexandria from its Audience?”, which took me some time:

https://blog.sleepingdog.org.uk/2024/06/why-does-poor-things-movie-hide-british.html

Having read the 14 pieces of pretentious.niche, tosh from the Guardian, I can only lament the fragmentation of Western culture in our time- no-one who went to the Rex or the Vogue in the 50’s(Gray’s local cinemas) could conceive of viewing an entertainment in these ways!

Another thing that annoyed me about the Poor Things movie was that it cut all the Russian things out of the novel. The ship was no longer Russian, we lost the (sympathetic) Russian gambler, and why? Was it for Ukraine? We lost Odessa too, although maybe it was just unrecognisable, was that for Ukraine? All this does is hurt Ukraine.

Yes, a deeply insightful review that links pertinently with the website the review is in. Gray apparently was agreeable with his novel not being set in Glasgow. Bringing his novel to an international film audience,,he felt would create the conditions for more folk to read this novel and his other ones too. That is clearly happening at this time. Yet again, Gray has triumphed.

As for those irate feminist critics, I think that ‘Is the film feminist?’ is the wrong question – too definitive. Better to ask ‘What does the film do for feminism?’ and the answer to that is ‘loads!’, as Mike points out. Just watch that fabulously hilarious dance scene to see a woman in control

The dance scene is epic Emrba

You’re bang on the money here, Mike.

Thanks

A good article, which brings out the difficulty of connecting two incommensurable media, novel and film. There are similar difficulties lurking within Alasdair Gray himself. In ‘real life’, Gray’s politics contained a big chunk of old-fashioned, Attlee-era socialism, combined with a John Maclean style commitment to Scottish independence. This implies a lot of welfare-state type collectivism, far removed from most ideas of anarchism.

As a fiction writer, on the other hand, Gray let his imagination run riot – anarchism on steroids. Poor Things the novel is dizzyingly self-referential, with in-jokes shooting off in all directions. It is also a paean of praise to Glasgow as a physical place and a historically-rooted culture. Much of this richness is inevitably lost on non-Scots, still more on non-Glaswegians. (How many contemporary readers can identify Sir Patrick Geddes, far less John Caird? How many readers can distinguish a genuine Tennyson quote from (I think) an Alasdair Gray parody of Kipling?)

So I agree with Mike. Poor Things the film is not Alasdair Gray but it does catch genuine elements of his work. Poor Things the novel exists on a plane far beyond any possible film.

Thanks Dennis, I agree Alasdair was full of contradictions, aren’t we all!

@Dennis Smith, indeed, Poor Things is not a socialist novel; it is a bourgeois novel with socialist mini-lectures (some of which I found interesting); and no collective action except a couple of tiny sparks conveyed by hearsay well off-stage (with positive and negative aspects), or referenced later (like WW1 which wasn’t socialist). It draws on the idea commons of bourgeois literature, see the Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels (1848):

“The intellectual creations of individual nations become common property. National one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness become more and more impossible, and from the numerous national and local literatures, there arises a world literature.”

So Marx and Engels describe a bourgeois idea commons that Gray ‘filched’ (his word) from: “What morbid Victorian fantasy has he NOT filched from?”

Similarly, I cannot see any socialism in the examples Gray’s graphic work selected on BellaCaledonia’s pages. Perhaps Gray’s habit of blurring fact with fiction extended to his own life. Perhaps we see the dangers of the Cult of the Creator and affectations that earning artists may employ.

The novel revolves around the possession of Bella, and depends upon a shoddy contrivance (General Blessington oh-so-conveniently turns out to be a caricature of imperial evil) used to retrospectively justify actions which are serious moral crimes. The institutions of marriage, seduction etc are all bourgeois depictions which are rather celebrated than challenged in the novel.

What a brilliant review. I really want to see the film now!

Thanks Paddy

Enjoyed your piece& Dennis Smith’s take on it- it’s certainly true a Glaswegian of Gray’s vintage gets a lot of additional pleasure from it’s rootedness- much more than Dubliners get from Ulysses..

Read the book because of the film and your earlier review. Good to read someone who is prepared to be open minded about what they’ve seen/ read. Shall have to see the film now.

Great stuff Mike and a very good point about the broader, underlying politics: I have not heard any critic or reviewer mention it as they are too obsessed with is it feminist or not question, and all the sex. I was disappointed in Ahmed’s comment as she is generally pretty good. But in this case she shows ignorance.

@Niemand, in what way does Samira Ahmed show ignorance?

As far as I understand it, erotomania (not listed by NHS Scotland Inform) is a delusional condition. But the text of the novel (I have not seen the movie) is disturbingly close to the Metropolitan Police treatment of child sexual abuse victims, labelling them ‘promiscuous’ etc.

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2024/feb/09/met-police-officers-dissuaded-children-making-sexual-abuse-claims-report

which is a clear example of victim-blaming.

Indeed, Godwin Baxter’s admission (p68) is one of criminal intent:

“I did it for the reason that elderly lechers purchase children from bawds.”

whatever later transpires.

What is Eric Gill’s influence on Alasdair Gray, and on Poor Things in particular? He’s referenced briefly in the novel, among many others, but in a specific light of support.

OK, no biters, so here’s the thing that strikes, me, having seen comparable works by Eric Gill and Alasdair Gray on a Scottish museum website, and finding online assertions that Gray said Gill influenced him. The timeline of the (Wikipedia says) 1989 revelations about Gill:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Gill#Sexual_abuse

and the 1992 publication of Poor Things suggest that the revelations may have been in Gray’s mind when writing the book. As I said, Gray references Gill in it (p309):

“So although Victoria McCandless placed advertisements for A Loving Economy in the major British Newspapers it had only two favourable notices: one by Guy Aldred in an anarchist periodical, one in The New Age by the stone-carver and typographer, Eric Gill.”

Gill seems to have been a member of the Fabian Society (as well as the fictional Victoria).

Setting the above aside for a moment, my observation that Gray’s work does not typically look ‘socialist’ in character is partly based on reading David Graeber and David Wengrow’s account of how anthropologists interpret graphic art, in their book The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (and partly from some previous familiarity with socialist graphic art). Essentially anthropologists have a measure of how egalitarian a society might have been by the human figures being approximately equal sizes, essentially. Of course, the striking thing about Gray’s cover design of the novel Poor Things (at least my copy) is that the three central human characters are grotesquely mismatched in size.

I’m not saying that this rule of thumb always applies, nor that LS Lowry’s matchstick men are a definite indication of the artist’s socialist beliefs, but on the other hand, artists should be well aware of such symbolism. And socialist artists do use giants to make various points.

You may reasonably ask whether I’m just having a go at Gray or if there is a more serious, more general point. I would say the latter, since as someone who would be marked as a ‘political’ since studying politics, I’m well aware of the sensitivity of dissenting political groups (especially after the SpyCops revelations confirmed old tales and suspicions). But outside of state and corporate infiltration, there were many more accusations of ‘comrades’ who talked the talk but didn’t live their politics, especially domestically. And often it was women remarking on their comrades’ private misogyny. Now, Gray may just have been a mostly-harmless old perv, and his socialist beliefs expressed playfully rather than deceitfully; but can you say the same about Gill? I would say no. But what is Gray saying about Gill?

And finally, of course, I have to restate my ancient warning about the Cult of the Artist. Don’t go there. Ever. Please. I notice that Gray’s design was removed from BellaCaledonia’s masthead. That distancing seems sensible. And critical (re)views healthy.

Who cares? An air of persiflage about this,sure enough. All I knew about Gill prior to reading Gray’s book, was that he was an upper- middle arty-farty incestuous shagger-the reference to Guy Aldred- the pamphleteer,was welcomed by me as part of the welcome, dense, in-fill of Glaswegiana, which is part of the fun of the book for a fellow Weegie! Why Gill? Your thesis seems a malevolent stretch…

@Hugh McShane, I guess I’m more of a systems thinker than a literary critic, which is why I had to look up ‘persiflage’, but I’m more interested in how things connect than how works make me feel. I would rather people ask their own critical questions than fall into fandom, while tribalism in published science fiction seems to me like pissing in a communal swimming pool. Sure, there are people who say they are happy that Modern Who promotes London, Cardiff and er, Sheffield to the World, but is that really a worthwhile goal? I think Mary Shelley’s deliberate shifting of location was used to accentuate the universalist themes in her work. I don’t think that was the effect of Bella’s tour.

I was only mildly irritated during reading by Gray’s apparent fabrication of quotes and works from real people, as was mentioned by Dennis Smith, but when reflecting on Poor Things, I couldn’t see a justification for Gray’s intellectual dishonesty there. I mean, if you want to criticise Empire, why not use the actual recorded words of Imperialists, like serious historians Mark Curtis and Elizabeth Kolsky do, for example? The Internet has so many forms of fakery zinging about to dangerous and degrading effect, and where do all these misattributed quotes come from? In short order you get Nazi Steve quoting ‘Orwell’ on hard men.

I think you mean ‘who cares to ask these questions?’. Obviously fans care, but selectively. I didn’t care about the Gray and Gill connection until the fanfare over the Poor Things movie adaptation impelled me to read the novel, develop some questions about it, and try to answer them. At least you’ve addressed (sort of) one of my substantive points, so thanks for that. I presume Guy Aldred was referenced as a free-love advocate? I’ve only skimmed one of the pamphlets, and it was confusingly written (in a time of greater censorship, I guess).

My father often took me,on Sundays, to Royal Exchange Square in Central Glasgow in the early to mid 50’s to hear street singers& orators- Aldred may have been one of the latter, tho they were an eclectic bunch. Wiki ,interestingly ,notes that he donated his remains,initially, to the Anatomy Dept.of Glasgow Uni, s’thing Gray did also- that’s as likely a reason for his inclusion in the book, tho he had the same pot-pourri of views/opinions current among non- mainstream thinkers of his age, Inc.’free love’.