In Quest of a Film Culture

CINEMA, CULTURE, SCOTLAND: SELECTED ESSAYS BY COLIN McARTHUR, edited by Jonathan Murray, Edinburgh University Press (2024)

Colin McArthur is a leading scholar of mid-twentieth century Hollywood cinema, popular American film genres, filmmaking in Europe and British television, and a commentator on the representation of Scotland in film and the institutional culture of film production. I remember avidly reading those of his articles that appeared in the international literature, arts and affairs magazine Cencrastus in the 1980s.

Jonathan Murray, Senior Lecturer in Film and Visual Culture at the University of Edinburgh, has provided a very valuable service by bringing together thirty-six essays by McArthur which appeared in a wide range of books and periodicals between 1966 and the present day. McArthur himself provides additional commentary and an Afterword.

Colin McArthur was a secondary school teacher before joining the British Film Institute (BFI) Education Department as a Teacher Adviser in 1968. He was appointed Head of Film Availability Services in 1974, his title later changing to Head of the Distribution Division. He remained with the BFI until 1984, later becoming a visiting professor at Glasgow Caledonian University and Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh.

The critical perspectives of French film theorists such as André Bazin in the magazine Cahiers de cinema were an important influence on his writing. Early essays in the book include an analysis of the Polish director Andrej Wajda’s film Ashes and Diamonds (1958) and works exploring the culture and history underlying the Western, film noir and gangster movie Hollywood genres. He was an early champion of the idea that Hollywood cinema was a legitimate object of study. In pieces written between 1995 and 2000 he highlighted the erasure of historical and political context from later readings of the cult movie Casablanca (1942) and the neglect of the class dimension in critical reviews of the films of Alfred Hitchcock.

McArthur first turned his attention to filmmaking in Scotland in his essay “Politicising Scottish Film Culture” published in New Edinburgh Review 34 in 1976. Written in the period when the establishment of a Scottish Assembly and devolved government were anticipated, he employed the provocative mixture of polemic and academic analysis that was to become characteristic of his work, arguing that Scottish filmmakers needed to break free of the constraints on the range of their output imposed by the institutions of patronage, embracing challenging and critical perspectives on Scottish history, society and culture. What was needed, he believed, was not just a change in the approach to film-making, but a radicalisation of Scotland’s film culture. The Scottish film scene, though small, appeared to McArthur to be fragmented, with little creative dialogue or debate between filmmakers, institutions such as Films of Scotland, the Scottish Film Council and the Edinburgh International Film Festival, BBC Scotland and Scottish Television, and film studies in schools, colleges and universities. He called for ideological analysis of Scottish films and television programmes, and the production of alternatives which offered critiques of the dominant aesthetic forms and social, political and cultural assumptions encountered within them.

In “Scotland and Cinema: The Iniquity of the Fathers”, first published as a chapter in Scotch Reels: Scotland in Cinema and Television, the book McArthur edited based on contributions to a three-day examination Scotland and film at the Edinburgh Film Festival in 1982, he began an exploration of the representation of Scotland and Scots in film which he was to pursue and develop over more than 40 years.

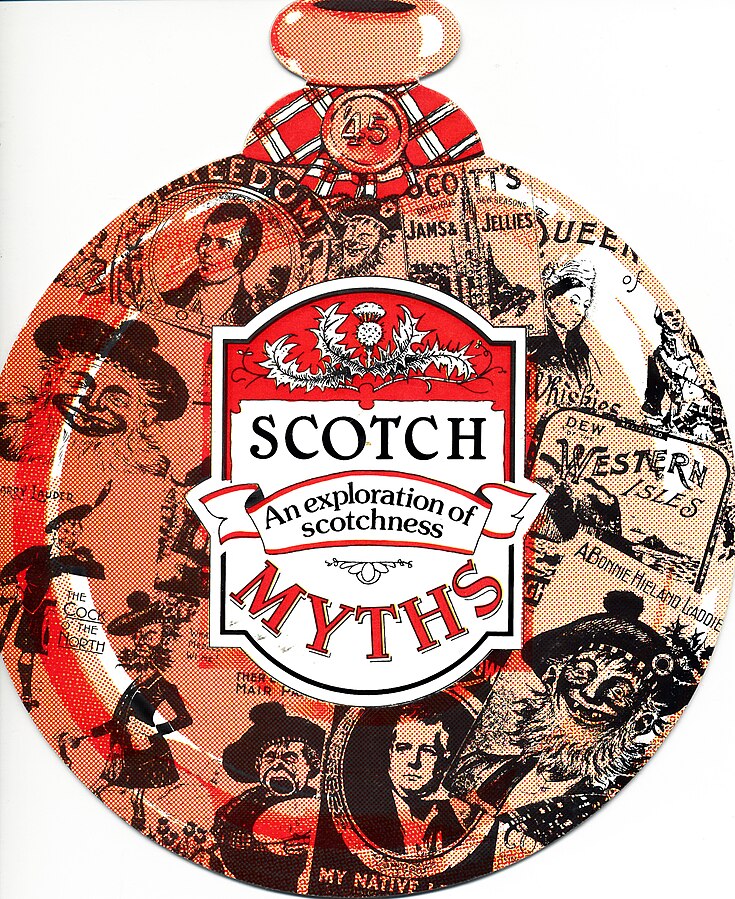

Drawing on the influential Scotch Myths exhibition mounted by Barbara and Murray Grigor in 1981 and the critique set out in Malcolm Chapman’s The Gaelic Vision in Scottish Culture (1978), McArthur argued that representations of Scotland in film, and more widely in popular art, culture and entertainment, were dominated by a limited number of powerful discourses, notably ‘Tartanry’, ‘The Kailyard’ and ‘Clydesidism’. [see The Traitors – Ed]

Tartanry has the longest pedigree, having its origins in the Ossian cult unleashed by James Macpherson in the 18th Century and receiving a further global boost in the context of Romanticism by Walter Scott and Lord Byron. Kailyard literature, and popular representations of Scotland derived from it, provided a depoliticised, escapist vision of a 19th Century rural Scotland dominated by the strictures of the Kirk in its established and break-away variants. Clydesidism, the most recent discourse, valorises the hard-drinking, self-consciously male culture of Scotland’s industrial working class.

McArthur draws on Chapman in arguing that ‘Tartanry’ is the product of a process of symbolic appropriation by which Enlightenment Europe defined, romanticised and tamed the Celtic ‘other’. In the intervening period, he argues, Scots (including Gaels) have come to define their identities within the framework fashioned for them to a remarkable degree. The Scot in the discourse of ‘Tartanry’ has become Homo celticus, a character is somebody else’s story. This helps to explain why many Scots have recognised and taken delight in even the most fanciful representations of their history and culture in British and Hollywood cinema.

In an essay published in Cencrastus in 1983, McArthur sees The Maggie, an Ealing comedy directed by Alexander Mackendrick in 1954, as offering a congenial fantasy in which the fey, wily and essentially Celtic ‘Spirit of Scotland’ outwits and seduces hard-nosed American capitalism. He points out that the economic reality in post-War Scotland was rather different, commenting that:

“What we witness in the production and consumption of The Maggie in 1953-54 is a society with no native tradition of seriously interrogating popular art caving under an ideological onslaught to the grotesque extent of mistaking grapeshot for manna.”

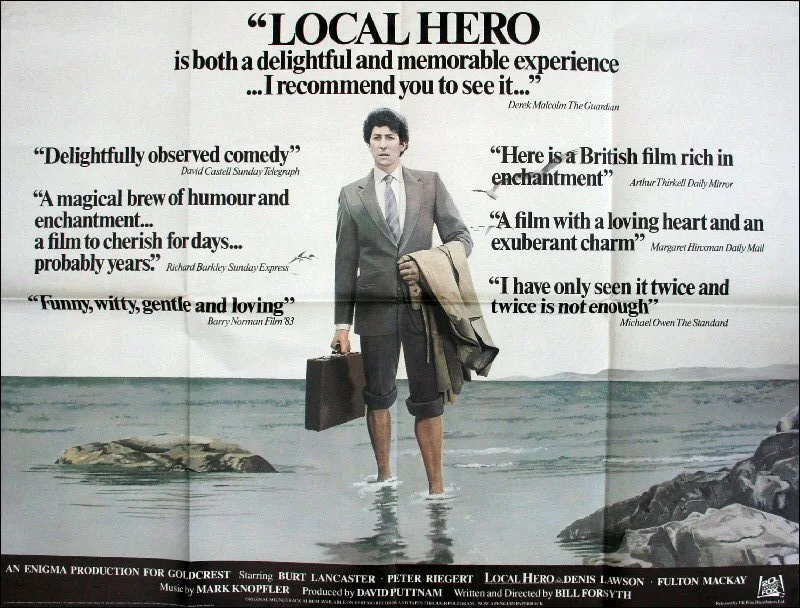

For those readers inclined to object that things had improved in the intervening 30 years, he pointed out that Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero (1983) had an almost indistinguishable plotline and received similar uncritical acclaim.

In expanding his critique of the representation of Scotland in film, McArthur developed the concept of the Scottish Discursive Unconscious (SDU), arguing that the dominant discourses of Scottish identity is now so powerful that anyone setting out to describe, comment on or make images of Scotland and the Scots, rather than producing a novel ‘personal’ take on the subject, switches to automatic pilot, slotting into a pre-existing and hegemonic bricolage of images, narratives, sub-narratives, tones and turns of phrase which have now become suspended in aspic.

McArthur lays much of the blame for failure to challenge this state of affairs at the door of the institutions established to support film production in Scotland. In a series of essays critiquing the film culture these institutions have promoted, he excoriates their excessive emphasis on commercial success, their fetishisation of the form of storytelling favoured by American cinema, their pursuit of the mirage of a ‘Hollywood on Clyde’, and their marginalisation of culture. He accuses the Scottish Film Council (1934-97) and Scottish Film Production Fund (1982-97), and later Scottish Screen (1997-2010), of favouring high-budget, orthodox narrative film intended to command attention on the European or world stage at the expense of lower budget films of greater cultural merit; and being overly focused on springboarding a few individuals into international film production rather than nurturing a healthy and diverse indigenous film culture.

This approach was crystallised in 1997 with the establishment of Scottish Screen, born out of Secretary of State Michael Forsyth’s irritation that the superior package of incentives offered by Ireland had resulted in much of Randall Fraser’s Braveheart (1995) being filmed there rather than in Scotland. More money was made available to fund Scottish filmmaking, but the model on which the new framework was to operate was to be an overtly neoliberal one, with culture subordinated to commercial imperatives.

As an alternative to this market-driven model, McArthur argued that there was a cultural necessity for what he called ‘Poor Cinema’, low-budget films which display cinematic literacy and engaged with the history or culture of the society from which they come. In his essay ‘’Artists and Philistines: The Irish and Scottish Film Milieux” (1998) he makes a scathing comparison between the commercial agenda being pursued by Scottish Screen and the cultural emphasis of the framework which had been put in place for the support of film production in Ireland by Michael D. Higgins when he was Minister for Culture and the Gaeltacht. He describes Scottish Screen’s policy guidelines and application forms during the thirteen years of its existence as a manual for crushing the life out of a creative project and warns Celtic filmmakers that: “The more your films are consciously aimed at an international market, the more their conditions of intelligibility will be bound up with regressive discourses about your own culture.”

McArthur argues that a healthy film culture requires both an awareness of both the process of filmmaking and ideology and discourse. He laments the lack of intellectual challenge or scrutiny in Scotland, pointing out that Scottish Screen never aspired to produce a substantial journal on the model of the BFI’s Sight & Sound. He sees Scotland’s media as having singularly failed to offer any serious cultural critique of cinema and filmmaking and is dismissive of most of what has passed for cultural criticism from the pens of Scottish journalists.

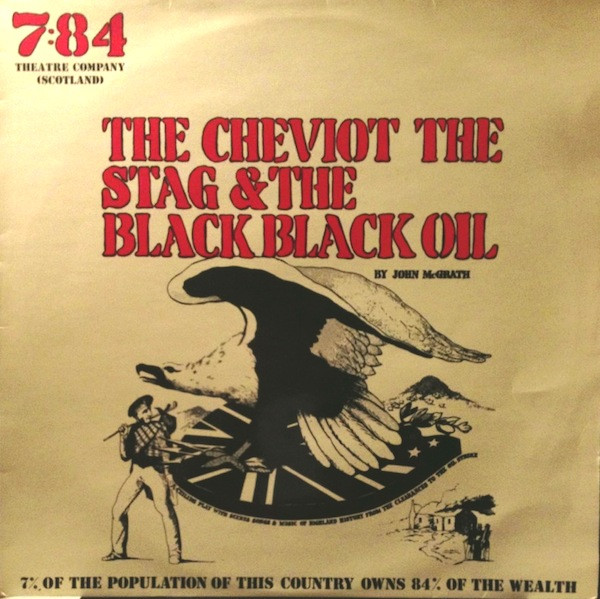

Two of McArthur’s later essays focus on the filmmaking of Murray Grigor, whose Scotch Myths exhibition was influential in the development of his own thinking on the hegemonic discourses of Scottish culture. Grigor’s Scotch Myths film was commissioned by Channel 4 and broadcast on Hogmanay 1982 as a challenge to the New Year offerings of BBC Scotland and Scottish Television, which were constructed within the discourses of Tartanry and Kailyardism which it lampooned. The film eschews a classical Hollywood narrative structure, makes extensive use of animation, and individual members of the cast migrate from playing one historical or mythical figure to another. McArthur sees it as sitting alongside John McGrath and John Mackenzie’s The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil (1974) and Ian Pattison and Colin Gilbert’s television series Rab C. Nesbitt (1988-2014) as one of Scotland’s most important contributions to a ludic modernist tradition – simultaneously playful and politically serious – going back to the Surrealists, James Joyce and Samuel Beckett.

Grigor’s Scotch Myths film received remarkably little critical attention, though Julie Davidson described it as “possibly the most creative and discreetly bitter piece of self-analysis to come out of Scotland in years.” It was received sourly by the Scottish film establishment. Afterwards, Grigor was conspicuously unsuccessful in securing support from the funding institutions for film projects with a Scottish cultural focus and was obliged to turn to work in the United States. McArthur claims that the shunning of Grigor’s work by the apparatchiks of Scottish film funding and broadcasting amounted to suppression, pointing out that the Scottish Film Council went so far as to ban the acquisition of Scotch Myths for its film library and the Scottish Film Archives. He makes a robust case for the belated recognition of Grigor as an auteur of Scottish filmmaking and argues that by denying him production funding Scottish institutions missed the opportunity to develop with him a progressive take on Scotland’s history and culture.

In his Afterword, McArthur concludes, perhaps rather too morosely, that the arguments which recur throughout these essays are no longer in favour with film and cultural academics. I believe that many of them are every bit of valid and relevant now as when they were originally made. One of the propositions he makes in this important body of writing is that the film movements which have achieved international recognition have emerged from periods of profound social change through the efforts of cadres of intellectuals and artists concerned with issues of class and nation. We appear to be in such a period. Can Scotland build a film culture capable of engaging confidently and distinctively with the challenges of these times? Do we have politicians, broadcasters and funders with the courage and imagination to support that? And do our new media have the inclination, critical capacity and cultural literacy to nurture the endeavour?

It’s probably only a slight exaggeration to say that the French Consulate in Edinburgh does more to promote French films and cinema going in Scotland than Creative Scotland does to promote Scottish films and cinema going in Scotland.

The French Consulate, through the French Institute, holds an annual French Film cycle, which is a mixture of old classics and recent releases. It also has a library of French films you can borrow unless I am mistaken. When did you ever hear of a cycle of Scottish films, in Scotland or anywhere else? How can we talk about a national cinema when the corpus is as elusive, scattered and fragmented as it is? When there is so realtively little written about film in Scotland? (though recently, more) When there is no centre?

We could have these things too if we had a mindfully pro film culture, but we simply don’t. A national Scottish filmotech, in line with the European model to run film cycles and all kinds of retrospectives, to serve as a centre of research and a national film library, and as a venue to host foreign film-makers coming to give masterclasses and talk about their work, as well as other events, would be a game changer for what Graeme Purves rightly alludes to as a “film culture”. It could also publish a magazine or journal, even just a quaterly one.

The problem is, being part of the anglosphere, my impression is that young people into film probably just don’t get the chance to see many films out of the bandwidth of the US commercial cinema because the prevailing view in the angloshere is that Hollywood is the be all and end all of cinema and anything outside it of marginal interest when of course the complete opposite is true.

Ultimately, MacArthur is right about decades long institutional failure and lack of ambition (I am less convinced about his “discursive unconsciouss”), and at the end of the day, there has never been a truly great Scottish film-maker, of the stature of say, Bergman (Sweden), Rossellini (Italy), Jean Renoir (France), Buñuel (Spain), or anything like the “New Waves” which swept the world in the 60s and 70s and changed everything. No Fassbiner, no Godard, no Truffaut, and most of the good film-makers we have today end up going to shoot films in the USA or London…

Bill Douglas was a great film-maker, but he didn’t get to shoot many films at all…

But there are models out there for a country which such little money for film. The Irianian cinema of the last 30 years is one of the great artistic achievements of our time in all of the arts. To make all those small, clever, intellectually engaging and playful films in the face of a mudering Islamo-fascistic State apparatus, with Iranian film-makers thrown into prison, banned from travel, and subject to house arrest, is one of the most amazing and uplifting stories of our time. How do you resist the politics of oppression? Make a film, with what you’ve got, your phone, a digi camera.

Jafar Panahi’s hilarious NO BEARS is currently on the BBC iplayer – possibly the only foreign film on the menu – and gives a flavour of that cinema, and some of its recurring themes, and, of course, Mohammad Rasoulof’s THE SEED OF THE SACRED FIG is up for an Oscar next month…

These film-makers of Iran are truly inspirational human beings…

McArthur mentions Iranian cinema in his advocacy of ‘Poor Cinema’. I have seen some of these Iranian films, having misspent some of my middle age at Filmhouse!

How could he not mention the Iranians? They basically have invented a whole kind of film, almost always with a car involved, Abbas Kiarostami, the greatest of them all, most of his films take place in cars, from AND LIFE GOES ON, to THE TASTE OF CHERRY, to TEN, three absolute masterpieces of film-making. The fact that they are all very, very, very cheap films, is a plus, but first and foremost they are great films and have sparked film-makers in other countries to follow the same path…

Though MacArthur doesn’t call it Poor Cinema, he calls it Cinema Pauvre, that is, he deliberately uses the French word for poor I’m sure for a reason, namely, that we need to be more plugged into what’s going on in World Cinema and for that we need a Filmotech. We need to look at some of the models out there for an artistically thriving industry and draw from them and for that, the films have to be avialable, the deabte has to be ongoing.

I should also add that there is such a Filmotech in London, of course, the British Film Institute, and it publishes widely on film. Sight & Sound is its monthly magazine as you know and there are all sorts of cycles and retropsectives on there – some of which make it up to Scotland at the GFT or EFH – and masterclasses and a whole library of BFI publications on films and film-makers. We need the same in Scotland.

In AND LIFE GOES ON, a father and son set out in the aftermath of the catastrophic earthquake of 1990 to try and find the actors from Kiarostami’s previous film, WHERE IS THE HOUSE OF THE FRIEND?, which struck the country on the day Scotland were playing Brazil in the 1990 World Cup. It’s one of the dialogues of the film, the father thinks a different match was on when the earthquake hit, but the son insists it was Scotland – Brazil (and it was).

And this is the thing about films, they are passports into whole other worlds which we also form part of, vaguely, distantly, just as a name. You watch these Iranian films and you really get a feel for Iran and its people – nothing like the tyrannical regime we see on the TV. Just like us in so many ways…

A very interesting and thought-provoking review, thank you. Showing films – usually with subsequent discussion – used to be an integral and important part of the radical left playbook. I wonder whether this agitprop tradition, suitably updated, could be relaunched in Scotland today.

I do hope it can, Paddy! But, as McArthur argues, we also need a supportive framework of funding and critical engagement involving specialist journals and magazines and the wider media.

Very good! It is great to read of McArthur and Grigor.

I have Scottish Reels which is excellent. I have written myself about Films of Scotland and found McArthur’s (and others’) critiques invaluable. What I would say about the best of that output is that its clear political inadequacies begin to dissipate in importance over time when you see (and hear) some of the impressive aesthetic innovations of the best of these films. It is a shame they are today so unrecognised as there is some quite groundbreaking and excellent work in there.

Grigor of course once headed up Films of Scotland. I met him a few years ago (a very decent man) when I was researching prolific composer for FoS, Frank Spedding and he introduced me to some of his own architectural films: Hand of Adam is really excellent. But it is his Space and Light about the then (1972) newish seminary at Cardross that is his masterpiece. I have not seen Scotch Myths nor his earlier subtly satirical film Clydescope (featuring Billy Connolly). And I just came across his Big Banana Feet a kind of Dont Look Back tour film of Connolly in the mid 70s. His work really deserves a proper retrospective.

And I agree with the overall premise of this article. We need more films unashamed to look to home, but without the usual tired old cliches, and unafraid to be critical. Personally I would also like to see more aesthetic innovation, or at least that which goes against the zeitgeisty commerciality that gets so very tiring and ends up being able to express very little (and is also a sign of yet more playing it safe or even rank cowardice). It is like the vital link between form and content in art has been forgotten! How impoverished us that?

Murray Grigor’s films are not easily accessible. There are some things on youtube, but most of his work is hard to find as I found out when I tried to see Scotch Myths after reading Scotch Reels a few years ago now.

In any case, this is all just pie in the sky. Nothing will change in Scottish film. The SNP’s government’s policy in film, and Scottish culture in general, has been one of continuism from New Labour, so, Screen Scotland is part of the UK film industry, rather than an autonomous body with its own philisophy, objectives and goals (albeit to be fully autonomous and the whole thing to make sense, a stand alone Scottish BBC Scotland would be indispensable).

The UK film industry, in turn, is conceived of since the time of George Osborne at least as basically part of the services sector, with the focus on attracting huge, multimillion dollar Studio productions to shoot in the UK via tax breaks, just as you might incentivize capitalists in any other industry to come and work here. The crumbs from the table go to a diminishing pot of soft subsidies for UK film-makers, and if an original voice manages to break out, then that’s good, but if they don’t, then that’s just too bad and no one’s fault.

Of course, it should be the othey way around. Scottish film institutions should be geared to finding new talent and making it possible for Scottish film-makers to find their voice. As far as I know, there has been no film made about the silent Scottish revolution which has taken place over the last 15 years or so. How is that possible? No one would dare to write it probably, no one wants to rock the boat. Well, that is excatly what Jaffar Panahi does with his films, stir it up, rock the boat, resist…

Then there are all kinds of other small, but very prestigious films which cost very little, the poetic nature films of Michelangelo Frammartino (LE QUATTRO VOLTE) , for example, or the minimalist dramadies of Hong Sang-Soo, and very little has been done in documentary either, Mark Cousins aside…

It is a depressing picture. The reason I mentioned a retrospective on Grigor’s work (and there are others) is that recognising past talent can be inspiring for others. I agree his films are hard to find – he gave me a copy of Hand of Adam himself. Space and light is free on the NLS website.

The only thing I would add is it is possible to make documentary very cheaply indeed (if you have basic digital equipment, in essence it costs nothing but your time – I know because I have done it) and the fact there is not more in that vein is down to filmmakers themselves and a kind of reluctance to do something, anything.. ou have to work with what you have got and If you are motivated you will. Films of Scotland had no funding for filmmaking and yet somehow, they made hundreds if films. They did this by the serious compromise of the sponsored documentary which did negatively affect the films but along the way, did some great things nevertheless.

I cannot remember the filmmaker’s name but a well known figure was asked by a film student how can they get started when they cannot get any funding? He said that in this day and age (i.e with the pretty high quality cheap tools available) you should be making no-budget films, getting on with what you could, exploring, experimenting shooting and shooting basically and stop complaining about money all the time and doing nothing. There is something in that – one can talk oneself into inertia and despair and a film culture only grows from the films themselves, the talent, the ideas, the *motivation*, not money itself. Punk rock was a DIY youth movement with very little money whatsoever in it at first, yet it changed the musical world – no-one was talking about ‘funding’.

Hi Niemand

I actually think that things look a good bit brighter for Scottish cinema than they did, say, 10 years ago. Screen Scotland have widened their net and accept smaller films these days, like Luke Fowler’s work, and both Charlotte Wells (AFTERSUN) and Ben Sharrock (LIMBO) are two really good directors who have just recently broken through. I admire their work. Ben did a tiny film in Spain, EL PIKADERO, which almost no one will have seen, but I have and it shows the guy is a born director. As for Charlotte, well, she is a rising star…

There is not a lot of money now, I think they have 20 million for everything, but there is a lot more than there was 10 or 12 years ago when there was just 3 or 4 million for production, it was an embarrassing figure. And then, even though I don’t like TV very much, SHETLAND has been a big success, as has GUILT and obviously BABY REINDEER.

I think you have to focus on what’s doable, and a National Filomtech is that. It could be called The Sean Connery National Fimotech of Scotland, and the first cycle it shoud run would be one of Sean Connery’s films.

Because Sean Connery is by far the single person who has done most for putting Scotland on the film map in our time. And now 5 years have gone by since he died, and no one has organized a restrospective of his work.

The reason for that is simple. It’s not the job of anyone to do such a thing. It’s not in the remit of Creative Scotland to organize a Sean Connery cycle of films, and where would they screen anyway?

We have to use what we’ve got a lot more…. Sean Connery, an international legend, for example.

It would do so much for the prestige of the industry to have a venue, a centre, a hub, a kind of home….

Excellent, and encouraging, points!

Indeed. I had a pretty good idea of the answers to the questions in my final paragraph when I posed them! But I don’t believe in being fatalistic or defeatist. What is striking is that there has never been any real challenge to the neoliberal funding model crystallised in Scottish Screen only two years before the re-establishment of a Scottish Parliament. Subsequent devolved administrations, Lab/Lib, SNP and SNP/Green, have simply accepted it as pre-ordained and immutable, and it seems to suit the officials administering it just fine. You have already put your finger on the lack of ambition. It is very striking.

This is just abusive. You make no substantive point. We won’t be accepting comments such as this from now on. Your comment will be deleted.

I take solace in having mastered the difference between a full stop and a comma. 🙂

Where are the movies depicting a future Independent Scotland? I mean, if Culloden (1964) director Peter Watkins had gone on to shoot Punishment Park on a Caledonian grouse moor instead of a Californian desert, perhaps we’d have a thriving genre of dystopian Scottish science fiction movies by now.

But perhaps the other place to look is within franchises and collections? Have depictions of Scotland moved on from that episode of beloved children’s animation Bagpuss or Doctor Who and the Zygons, in the recent Simpsons (Wullie’s wedding), the X-Men (Edinburgh again), or Curses (selkies)? I guess there are adaptations from, say, graphic novels that might be in the offing.

[ If any cinephile expert feels community-spirited, they might want to update Wikipedia’s Cinema of Scotland page (I guess there should also be a section ‘scrapped in Scotland’):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cinema_of_Scotland ]

Or perhaps as games become more cinematic than cinema, we’ll see the richest cultural expressions there?

And maybe, as the stock of pretentious arthouse films continues to wane in conjunction with the outpouring of scandalous revelations about dreadful movie people, we will at some point be very thankful there was no Scottish ‘New Wave’? I mean, we’ve already got (if not got over) John Knox. I would be interested in seeing an international collaboration critiquing Scottish colonial crimes which if hasn’t happened yet it long overdue (yes, I checked Wikipedia’s List of films featuring colonialism page). What’s the point of celebrating the French ‘New Wave’ if their culture is rotten with atrocious misogyny and they suppressed for decades the best movies about their own colonialism and WW2 collaboration?

Your point about the presence of Scottish films and film-making on Wikipedia is a good one. What there is is dominated by official and institutional history narratives, with little evidence of critiques or alternative perspectives. Compare and contrast with the presence of Scottish theatre on Wikipedia, which does convey some sense of creative range and variety.

It’s great to see this book (and review). Colin taught me for a little while in the early 1990s at Middlesex University (invited by Judith Williamson I think). Coming from a working class background myself, my conversations with him gave me the confidence I was often lacking.