An Architectural Brigadoon: The Two Fires of Glasgow School of Art

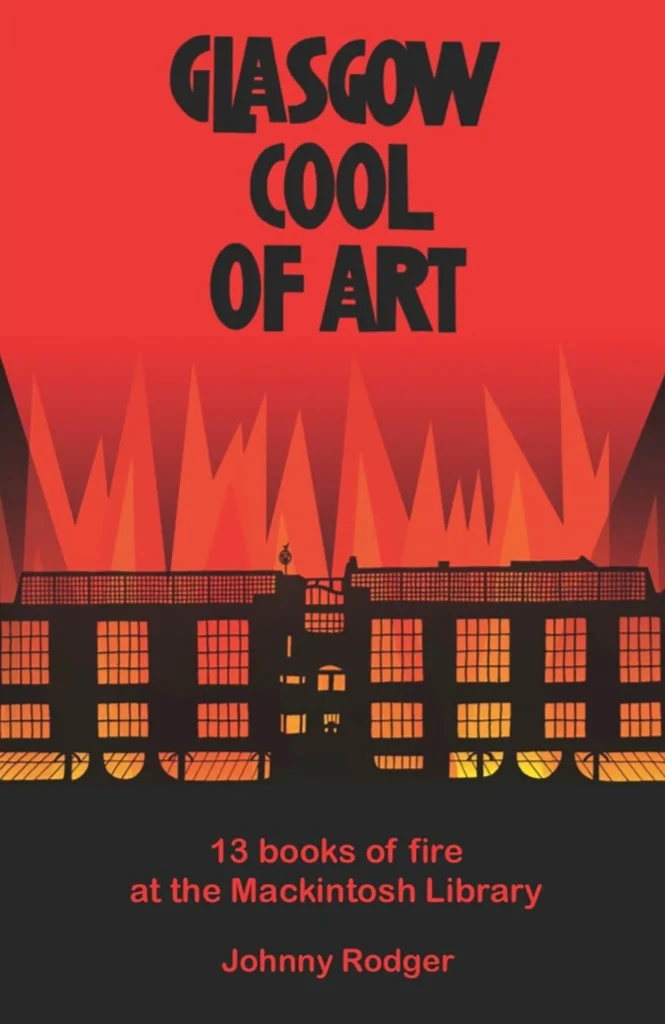

Glasgow Cool of Art: 13 books of fire at the Mackintosh Library, by Johnny Rodger, The Drouth, 2022, pp 170.

For all their remarkable persistence, cities are made from fragile components. Buildings, roads, railways, pavements, sewers, canals, bridges, parks, telegraph poles… every part of the great glorious mess demands constant human attention otherwise it will be gone in a shockingly short time. Weeds grow, sewers crack, riverbanks erode, bridges fail, and buildings: well, sometimes buildings burn. And sometimes they burn more than once.

The twice-burned Glasgow School of Art’s Mackintosh Building is, of course, the subject of this short but intense book in which philosophy and emotions jostle for position with the narrative of the two fires which first damaged and then destroyed that most beloved of city structures. Rodger is GSA’s Professor of Urban Literature and closer than most to both building and to the events that swept it away. From his office, Rodger enjoyed “the most beautiful view of a façade in Western Architecture” and it is that western elevation, housing Mackintosh’s famed library “hang[ing] in the air over Scott Street” which drives Rodger’s meditation on the ultimately finite encounters between people and buildings and what it means to construct and reconstruct.

Perhaps the most arresting encounter in the book is Rodger’s description of the day he visited the almost-completed reconstruction of Mackintosh’s exquisite library, the seemingly irreplaceable jewel lost in the first fire. Despite the newness of the wood so carefully sourced and selected from America to replicate the original, and the knowledge that what he is seeing is a reconstruction, Rodger is nonetheless both moved and convinced by what he sees: however new, this really is the library he knows and loves reborn. On that day, more than any other, he is witness to the (almost) culmination of what in hindsight seems like a miracle born of extraordinary commitment and achievement over an extraordinarily short period of time. I was also lucky enough to see the building during this restoration phase and looked forward to the opening of a new Mack building, the same-but-renewed, and to the catharsis that felt somehow owed after the drama of the first loss.

The archaeologist Ian Hodder writes about the entanglement of humans and things and about the very particular strangeness of our miniscule and short-lived (in cosmological terms) planet. Where the laws of physics require, inexorably, the breakdown of structures to their least complicated and most chaotic state, we humans are engaged in a constant battle against this inevitable entropy. For Hodder, the evolution of human society has been shaped by the creation and accumulation of ‘stuff’. The more material objects (including buildings and their contents) we own and rely on, the more our lives are devoted to maintaining and replacing our ‘stuff’ to the exclusion of other activities. This is not necessarily a criticism but an observation (although Hodder does draw our attention to the environmental catastrophes and wealth inequalities associated with societies built on the accumulation of things). The more interesting discussion is how different human life might have been if our societies had not evolved in this way and if we were not responsible for the stewardship of all the countless things that we have made and now need to survive.

Rodger’s rich dissection of the social processes centred around the Mackintosh Building, from its first inception to its (final?) fiery destruction similarly invites the reader to contemplate why a building is worth so much human endeavour. Rodger leads us through the complexity of how buildings get built in the first place; how plans are derived and evolve; and how financial, social, political and aesthetic considerations become concrete. His analysis is kaleidoscopic and invokes Super Mario as easily as Vitruvius. There’s something here too of that old joke about the high-quality broom that has lasted for years and only needed four new brush-heads and two new handles. The question of whether it is the same broom is more complicated than the joke implies, and questions about authenticity, replication, and reconstruction inevitably permeate this book.

In one of many thought-provoking vignettes, Rodger shows us the depressing and dirty work of sorting through the “metre high” piles of black and sodden remains on the library floor to find fragments of Mackintosh’s stylised lamps (which, now rescued and reconstructed can be enjoyed again, hanging in the School’s Reid Building). The violence of that first fire twisted and blackened the pieces, but also revealed the original colour and position of the lamps, both of which were at odds with the long-held understandings of scholars and library users. Things found in the “wrong” position led to the notion that changes to the original design or changes that just happened as the building was used could be reversed as the library was re-built to create a more perfect, more authentic version of Mackintosh’s vision. This idea appears as a balm during the dismal triage of salvage and for those mourning a building whose very particular characteristics had triggered joy or inspired their own artistic efforts. Something lost could be given back, but better and truer and more precious even than before.

How cruel then, how painful that just as the building was about to re-open it was lost again, and much more so: now just that invisible hump of stones on a hill completely obscured by a scaffolding so complex it seems like a building in its own right. Cruel too that the terrible gravitational pull of the inflagration took the adjoining ABC/02, itself of historic significance, and destroyed businesses and damaged lives across Garnethill.

Rodger tells the story of that second disaster through the very personal lens of his own experience, and as part of an on-going dialogue with his teenage daughter, who had just started to get interested in her dad’s work and who points out, shockingly, that they could both have been caught up in the flames as they left Rodger’s office late that night. No one was killed in either fire and no one was hurt, unless you count the emotional shock of those who witnessed the flames or cleared up afterwards and (more pertinently) those whose livelihoods or homes were lost as a result of the clearing-up operations.

Cities recover from these things, even if they don’t forget them. Lisbon still displays its scars from an earthquake in 1755. Warsaw and Dresden have reconstructed architectural treasures lost in World War Two. Some cities have chosen, like Coventry, to retain ruins as memorials to those lost in unthinkable acts or to build newly around them. Rodger’s daughter is the source of many insights in this book, but perhaps the most entertaining and enlightening anecdote is one in which the adults around her “with our wailings and gnashings of teeth” hog the TV and internet desperate for updates on the hideous news, watching with horrified fascination as the roof collapses live on screen, whilst she is “baffled and slightly irritated” at their reaction. It is just a building after all and one that, as Rodgers points out, has already successfully if very briefly been reconstructed. Why not just commission a new one? Why not commission lots of new ones, for that matter?

There’s something deliciously subversive about the notion of a Mackintosh School of Art Building for every street corner or one for every town, given how central our unique and fetishised architecture has become to tourism and to civic pride. It was not there, then it was there. It lasted for 100 years or so, disappeared, was rebuilt, was nearly back again as though nothing had happened, then like an architectural Brigadoon, disappeared back into the smoke. We could choose to move on and build something different and that would be OK, because future generations might not much care that it was once there and now it is not. Any afficionado of the Lost Glasgow Facebook group is more than aware of how many splendid buildings were once also ‘there’ and are now not, with no suggestion that they might ever reappear. The city has not found uses for many masterpieces that currently lie decaying.

Why then should we, as Rodger suggests, sing this one back into being? The answer seems to be because we can, brilliantly, with the plans left by Mackintosh and with the expertise available and we should, as David Crowley said about the ruins of Warsaw, because then we can forget what its absence means. The choice we have made as humans to fight against entropy and chaos, and to shape the elements around us into wonderful things does shackle us to their demands. We spend time, and money, and precious natural resources building and maintaining and fixing things that don’t really need to be there. Amongst all this human enslavement to the demands of stuff, it seems then unremarkable that a really great place that people loved and wanted to visit and mourned when it had gone should be resurrected. It doesn’t need to be there. But it would be nice if it was again.

Glasgow Cool of Art: 13 books of fire at the Mackintosh Library by Johnny Rodger is available from The Drouth price £10.00: https://www.thedrouth.org/product/glasgow-cool-of-art-johnny-rodger/

“Cities recover from these things, even if they don’t forget them”

We all learn from our mistakes (speaking as a retired Architect that spent many years at the GSA, Dept of Architecture as it was then) and hopefully there will be some detailed inquiry how this happened, not once, but twice.

What lessons were learned after the first fire that were put into practice?

What wasn’t done that should have?

Will any inquiry be undertaken or have I missed it?

All salient points, Eric, although outside the purview of this book which asks rather bigger questions about our human relationship with buildings and spaces. The inconclusive official report on the second fire has of course done nothing to help our very understandable urge to pin down causes and to ‘learn lessons’, whatever that much-used phrase really means. I liked the way Rodger looks past the notion of institutional ‘lessons learned’ towards a broader view of value and of an almost magical realist sense of the building emerging and then disappearing. Of course, had there been injuries or deaths we would not have the luxury of enjoying such a playful take on events: if there is tragedy here it is cultural rather than human.

Who wants to ‘forget what an absence means’?

on a walk by the burn

the place where I once saw a heron

pleases me as much as the heron did

now it will always have a name

the heron place

and in the name the story

a small one I can turn over

stonewise in my pocket

it fits my palm nicely

and swings with the rhythm of my walking

I’m surprised it’s taken this long for the school-cum-scene that brought us Martin Creed and the like to aestheticize the burning down of its own A-listed heritage. Hasn’t anyone suggested the fire was de facto artistic praxis yet? I’m thinking of Yukio Mishima’s nihilistic tale “Temple of the Golden Paviliion.”

Some years ago it was reported that GSA is one of, if not, the most socioeconomically exclusive HE institutions in the country. I wonder if steps have been taken to address that yet, or if doing so would be too “difficult” (ie, un lucrative).

There are indeed many architectural classics moldering in town. Greek Thomson’s St Vincent Street Church is the latest one to have completely escaped notice. Personally I prefer Thomson to Mackintosh. I also prefer the kind of people who used Thomson buildings to the kind of people who used the “Mack.”

“I also prefer the kind of people who used Thomson buildings to the kind of people who used the “Mack.””

What an odd thing to say – but, heh, everyone to their own preferences

Sounds like someone’s bitter about getting a KB off GSA… or mibbe just off one of the students!

I’m not sure Mizoguchi’s burning of the Kinkakuji in Mishima’s novel can be construed as artistic praxis. It’s treated rather as an act of liberation from the arsonist’s own stuttering (both literal and existential), which he attributes to his feelings about beauty.

Small anecdote: I knew someone who worked at the GSA (not in touch any more) and they commented that all the students they taught were English. More money from them of course as they pay full tuition fees and my understanding is that Scottish students, though subsidised, do not generate the same amount of money per head as the English. It was even stranger when we were still in the EU as EU students (EU as in overseas EU) were also subsidised.

It really is a very bad reflection on Scotland that we could allow this building to burn down….twice. That second fire really was unforgivable. A kind of national chip-pan blaze we can all be proud of.

A tonally idiosyncratic episode of BBC’s Click technology programme covers digital preservation work on Ukraine’s buildings: https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m001d2mb/click-can-tech-help-you-dress-better

Visiting cities virtually is commonplace these days. I have spent some time clambering over the cathedrals and roofs of Paris recently in a French-Revolution set episode of the Assassins’ Creed series, and I believe their reconstruction of ancient Rome featured in at least one online course. I think that is one of the generational shifts (along with the overdue death of tourism for climate reasons if nothing else): an appreciation of immaterial experiences (and sometimes having less stuff).

According to J-P Proudhon: The System of Economic Contradictions, or The Philosophy of Poverty, having less stuff (‘thrift’) is a guilty indulgence of those who have stuff they can enjoy, a bourgeois indulgence. Many people can’t afford the luxury of thrift. Proudhon was healthily suspicious of those baiseurs who preached thrift – the virtue of having less stuff – to the poor. He would have loved the ‘de-growth’ mob!

@Lord Parakeet the Cacophonist, you seem a little confused; were you not just praising Wikipedia, which releases us from having physical encyclopaedias (although I regard Wikipedia as more of an example of idea communism than of emergent democracy). Perhaps by the “‘de-growth’ mob” you are referring to the likes of George Monbiot, whose concept of ‘private sufficiency, public luxury’ seems a sensible approach for our world. In the UK, with the rise of subscription services (albeit with reported recent ‘cost of living’ downturns) replacing ownership of physical media, renting models replacing ownership in some cases, communal sharing online, perhaps the world has moved on since (you and) Proudhon. How much land does one man need?

I am not going to criticise those who ‘de-clutter’, even if those reasons are purported to be aesthetic rather than environmental. I have reread your statement “Many people can’t afford the luxury of thrift” and still find it nonsense. I lived years amongst an underclass and thrift was a life-preserving skillset that most I encountered demonstrated. I don’t recall any preaching, as such. Perhaps you suffered a religious upbringing that exposed you to much hypocrisy; that at least I was largely spared.

The digitisation of material artefacts is also pertinent to the return of looted items by the museums and collectors of European colonial imperialism:

“Weltmuseum Wien has committed to loans via the Benin Dialogue Group and the sharing of digitised archives in the Digital Benin project, which will create an online database of more than 5,000 objects held globally in public institutions by 2022.”

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/10/12/stealing-africa-how-britain-looted-the-continents-art

These digitised artefacts may end up in digital recreations of their original/historical built environments, as part of the idea communism of global digital commons, for people round the world to visit online and appreciate. And perhaps a virtual version of the Glasgow School of Art will be online too, housing an indefinite and growing collection of digitised artworks.

I wasn’t praising Wikipedia on the other thread; I was citing it as an example that might exemplify what David Graeber understood as ‘emergent democracy’: the political structures and behaviours that emerge from the free actions of many individual participants in the absence of central planning. Whatever else it is, don’t you think Wikipedia is a product of the free actions of many individual participants in the absence of central planning as well as, among other things, an equally fine example of the free and open sharing of information as a resource rather than its exchange as a commodity (aka ‘idea communism’)? Why do you dichotomise idea communism and emergent democracy anyway? Aren’t they ‘aa ae oo’, as MacDiarmid would have put it?

My understanding of Monbiot is that he doesn’t advocate ‘degrowth’ as décroissance (the decrement of productivity) but advocates rather a rescaling or revaluation of our productivity and growth as its measure. As far as I can gather from his production, he offers five principles from which the revaluation of productivity and growth could proceed. We should:

1. return to Aristotelianism by putting ‘the good life’ at the centre of our economy and measure growth in terms of how much our work increases human excellence rather than surplus value; this will involve

2. reevaluating work as a cooperative rather than a competitive venture to reduce working time and increase work-sharing;

3. organising our work around the production of goods rather than commodities;

4. organising our public decision-making democratically, in ways that enable people (especially from currently marginalised groups) to participate in the decisions that affect their lives and, in particular, in political and economic decision-making;

5. basing our political and economic work both locally and globally on the principle of public solidarity rather than on that of private gain at the expense of others.

These are very worthy principles (and you’ll have noticed that I’ve defended all of them on this blog at various times), but they crucially depend for their practical implementation of some relative conception of ‘the good life’ or ‘human excellence’. Which conception of happiness is the ‘true’ one has been a problem for Aristotelian ethics like Monbiot’s since the time of Aristotle himself. I personally think the matter is ‘undecidable’. You pays your money, you takes your choice.

I too have worked most of my life among people who have nothing. And my experience is that they deeply resent people (like George Monbiot), who enjoy relative affluence, telling them that not having or denying themselves stuff (‘thrift’) is some kind of virtue. As Proudhon remarked, that’s a particularly vicious form of pie-in-the-sky condescension. And that’s a true now as it was when Proudhon was writing in 1846..

The difference is that – unlike in Aristotelian times – or any era since – we now face an existential threat of climate catastrophe, which makes this less abstract than you make out.

As Monbiot has said – echoing other degrowth activists: “infinite growth on a finite planet is destroying the planet’.

But goods like care, education, security, etc., which some Aristotelian-minded ethicists, like Monbiot, would say collectively make up ‘the good life’, are not finite resources and are capable of infinite growth. The same Aristotelian-minded ethicists would say that this, the increase or improvement of our social capital or commonwealth, rather than the increase or improvement in the market value of commodities, is the kind of growth we should be pursuing as a measure of economic success.

Scott Meikle, a historian of ideas who works out of Glasgow University, gives an exposition of Aristotle’s Economic Thought in his 1997 book of that name, in which he contends that it was the backbone of mediaeval thinking about economic value, that Marx’s theory of economic value was based on it, and that it’s still the foundation of Catholic teaching,especially in its so-called ‘liberation theology’.

Scott also goes on to argue that Aristotle’s theory of economic value can’t be assimilated to capitalist ideology because its metaphysical foundation is incompatible with the Humean metaphysics on which the capitalist theory of economic value is built.

And therein lies the contemporary relevance and pragmatic value of Aristotle’s economic theory as a counterpoint around which resistance to the hegemony of capitalist ideology can coalesce, as it does in – for instance – Monbiot’s thinking on the matter of economic growth.

The Scottish-born intellectual nomad, Alasdair MacIntyre, who currently works out of the Centre for Contemporary Aristotelian Studies in Ethics and Politics at London Metropolitan University and the Notre Dame Center for Ethics and Culture, also uses Aristotle as a critical counterpoint to capitalist ideology, in his case in the field of ‘metaethics’ or the general theory of value.

Both Meikle and MacIntyre are worth a read from an anticapitalist perspective.

And, yes, we face an existential threat; such (‘being-towards-death’, ‘we’re all going to f*ck*ng die’) is the universal human condition. How we respond to that fate is, and always has been, the making of us.

I know this is a bit of a radical comment but I suggest just reading the book. It’s incredibly well researched and written with information and knowledge that are exclusive to the author, being one of the very few with access to the damaged library, as well as his expertise on Mackintosh and architecture. It’s an incredibly creative, thought provoking and uplifting read.

Read the book?!? Good idea Lorna! : )

I could not agree more, Lorna!

It’s a great wee book. Apologies for meandering back on-topic ; )

I’ve just bought it and started reading it and I’m very much enjoying the up-close insight and knowledge of the author.

For years, I always meant to visit the GSA having once scanned a coffee-table book about the famous library at a relative’s house. The library seemed so perfect and beautiful in those glossy pictures; simultaneously a cathedral and comfortable bothy. I deeply regret never having taken the time to go inside the school and take a look for myself.

The book brings me closer to Mackintosh’s masterpiece with the bonus of stimulating discourse. I’m very grateful it has been written.

I still feel angry that Mackintosh’s Glasgow School of Art was not looked after properly. I also feel strongly that it should be re-built.

The issue of whether it would just be a “replica” of the original is a non-issue in my opinion. The genius of the design was already there when Mackintosh completed his drawings. The rest is just craft and construction. If a building is made to Mackintosh’s drawings then it is his building.