Whatever Happened to the 500 Questions?

In fact these searing questions were, famously, mostly minor quibbles over the micro-mechanics of institutional handover – what will such-and-such a regulator be called, and so on. Although 507 questions seems impressive (they are in surfeit, though the numbering is very dubious, and involves a lot of ‘If so…’, ‘And how about…’), in what sense are these real risks specific to independence? Some questions are speculative; more are about minor bureaucratic reorganisation; many have in any case been absorbed into devolved powers, and many are just ludicrous, and were rightly lampooned: ‘167. What work has been undertaken to establish which tax reliefs would be available to Community Amateur Sports Clubs?’; ‘350. How much would a first class stamp cost in a separate Scotland?’; ‘466. What will Scotland’s international dialling code be?’

What is behind the document, though, is a moral high ground based in a homely protection from all unmediated risk, or what I have called ‘arithmetic patriotism’. Citizenship depends ultimately on a ‘natural’ evaluating authority that promises to ensure the continuity of a familiar lifeworld by removing any kind of change that can’t be repackaged as continuity. Independence debates were duly overwhelmingly ‘arithmeticised’ in the British press, and typically converted into dubious projections about ‘the economy’. Fundamental moral questions about whether nations should hold extinction-threatening weapons, or whether education should entail a debate-crushing debt-serfdom, even whether a genuinely shared public sphere was imaginable, barely appeared.

A Comfortable Descent

The spectre of an unmanageable ‘risk’ proved extraordinarily powerful, even as virtually everyone understood that the trajectory of the world being risked was inexorably downward. A comfortable descent into misery was better than the unmanaged ‘risk’ likely to create a more habitable society. More interesting than Better Together’s senseless gestures towards a ‘Dystopia of the Unknown’, though, is the way many of its ‘risks’ were realised under the Unionist status quo, where they would likely have been avoided under a Yes vote.

This is obvious from the outset, since the whole first section of the document is given over to the alleged difficulties of an independent Scotland’s continued membership the European Union. Most of the questions here describe minor diplomatic technicalities, but also darkly hint at catastrophic decline, or as Darling says, ‘how much we have to lose’. Within two years of the referendum, of course, the UK had voted out; and in fact Prime Minister David Cameron, worn down by internal Party pressures, had already pledged an in-out referendum in January 2013. Scotland voted 62% remain, easily the highest proportion of any UK ‘region’, and this, along with the arousal of latent constitutional interest by the referendum and SNP’s in the 2015 General Election, suggested a quiet constitutional earthquake, or a new awareness of democratic deficit.

This actualisation of Brexit by a process already in train by the 500 Questions also reverses its dark hints of economic chaos: Brexit, as was virtually undeniable by the end of 2022, added to the insecurity of food and other necessities, rapidly undermined international faith in the UK, and affirmed an unusual and disorienting decline. Responses relies on old habits, peaking with the Conservatives’ ‘mini-budget’, founded in embarrassingly misguided Thatcher retro-. The implacable faith in a unique British inventiveness that would make it a kind of new Singapore by now sat strangely with the realities of a post-industrial economy; but the same faith in British exceptionalism permeates the 500 Questions’ defence of every current institution, knowing that the inertia created by absolute parliamentary sovereignty in the UK (in fact, only the rUK) will help prop up these habitual beliefs. The risk of Brexit can then strangely be talked up in Scotland even as the British state sets about enacting Brexit, a process that would not have happened in an independent Scotland’

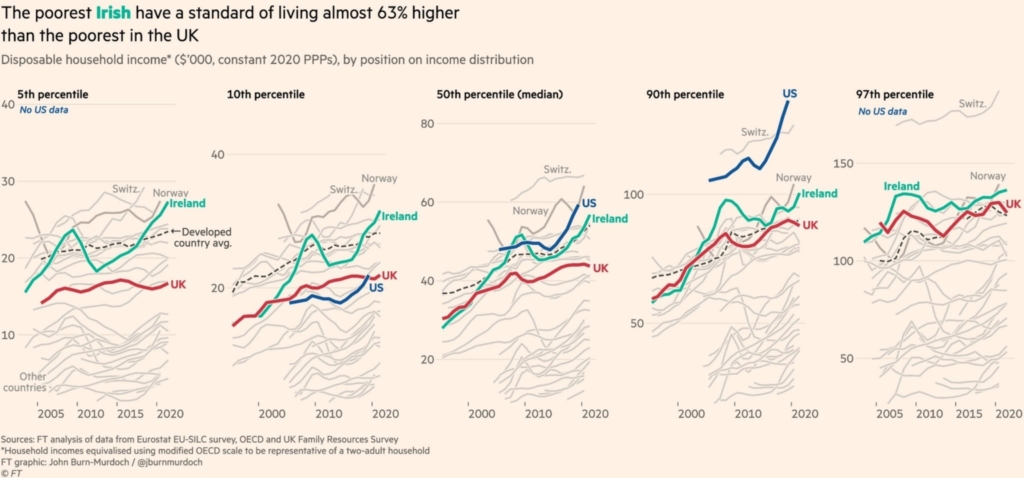

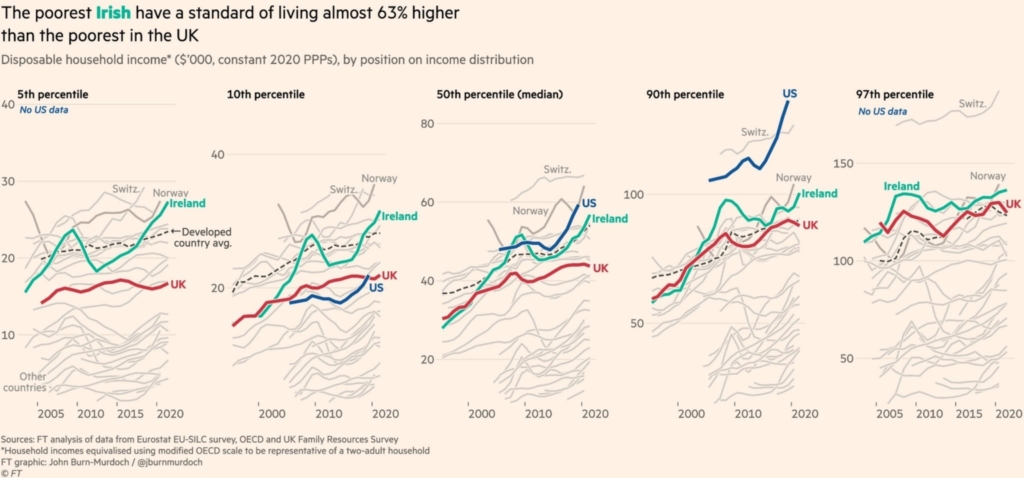

Similar is true for public spending and social priorities In May 2014 senior Labour figure Ed Balls stressed that independence would ‘perils’ for public services and for equality – a claim that went relatively unremarked in the British press, but an extraordinary one to make relative to a government demonstrably more committed to public services in health, education, and energy, while Labour had no no plans, for example, to have university tuition fees dropped or to reintroduce free prescriptions). The risk presented here is not to the public as a group of people, but to the public as a British brand standing in for a genuinely shared realm. The 2010s, meanwhile, saw an underfunding of organisations such as the NHS, and a post-2008 pumping of money to the economy drawn upwards by investors. The collapse of the NHS in 2022-23, senior medics now argue, had more to do with systemic de-funding than with the Covid emergency. Balls’s ‘perils’, here, then, are the perils of interruptions to the homely, familiar decline – despite the concentration of the ‘Health’ section of 500 Questions (292-309) vague implications about the ‘costs’ of simply renaming various departments.

Cold Hard Facts

Healthier Together

The effects of the de facto removal of public healthcare – like many other public provisions – don’t have to be laboured for anyone living on these islands in 2023. Paradoxically though, even as the healthcare aspect of the NHS disappears, the institution comes to be seen even more as a secular British religion. The less easily it provides healthcare, the more lionised it gets. In a sense this is unsurprising, since an emptied-out, complexly-outsourced bureaucracy is what the British public is expected to look like.

Medical and other professionals deserve to work in an environment in which they can actually do some good – and when nurses have to strike over conditions and pay, the British performance of the public good is in real trouble. The real telos of the British public realm is a kind of ‘private public’; deviation from this is a risk, and popular entry into this realm of risk is unacceptable. One question would be, at what level of dysfunction and outsourcing do we shift from saying that the British NHS is a public healthcare service that currently lacks funding, to saying that the UK has no such conception of the public?

Such conceptions of the public good have long worked as emotional talismans absorbing goodwill into a kind of anti-public, relying on gnostic beliefs of real care and provision, even through the experience of dysfunctionality and bureaucratic entanglement, and 500 Questions relies on this sense of untouchability.

And the same is true for many of the overlapping public services about which terrible risks are implied – transport, universities, energy – all of which were demonstrably more forward-thinking and inclusive in Scotland by 2014, and all of which, after the first independence referendum, continue to struggle with Westminster-Whitehall stasis. This homely inertia, ultimately, is what is being protected with by the easily-fixable issues of organisational restructuring in the 500 Questions. This is the public-as-usual that makes Ed Balls castigated ‘nationalists’; the risk is to a form of the public that draws people into a consensual isolation as individual market actors. Still, in a familiar motif Darling’s foreword, after independence, Scots would somehow no longer be acting ‘together with our friends, families, and workmates’.

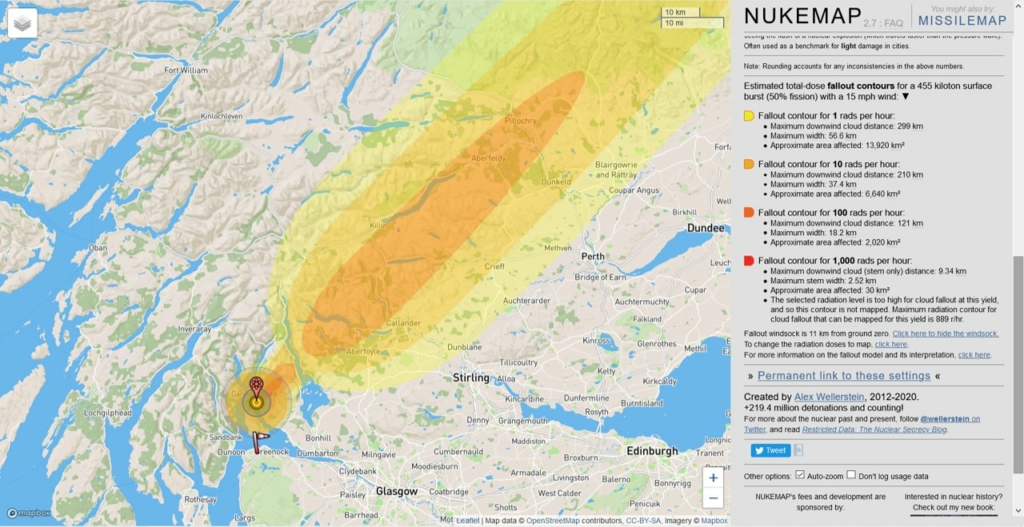

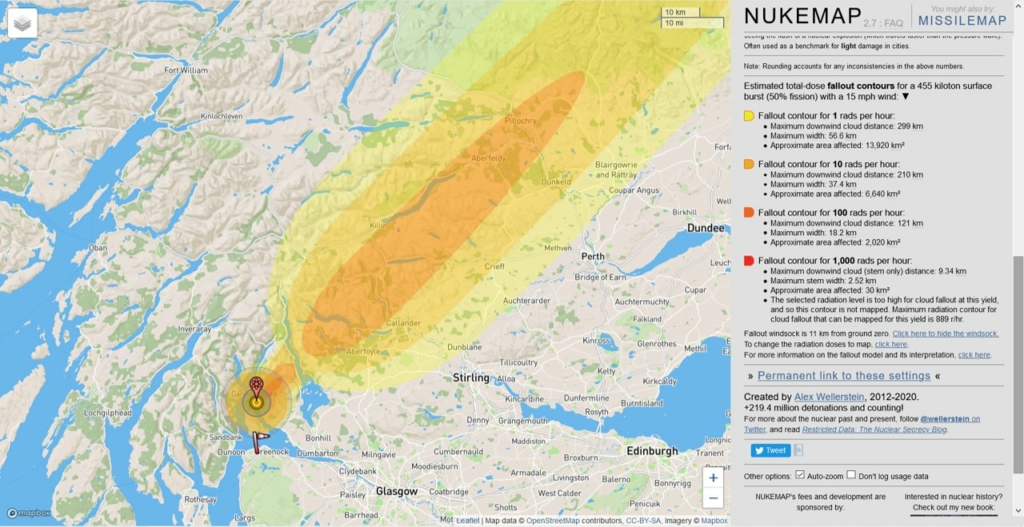

Beside this is an extraordinary omission, a key issue underscoring the referendum, something I have described as a fundamental historiographical split, and a pillar of the post-1945 British Welfare State: nuclear weapons. Tellingly, the only brief mention of the British nuclear arsenal at all in the 500 Questions (312) concerns the administration of compensation paid to people affected by past tests. Massive nuclear arsenals are assumed to connote security, though in practice they bring no such thing.

As is now again obvious, the threat from nuclear brinkmanship combined with the possibility of miscommunication or accident represents an existential risk comparable to anthropogenic climate change. None of this appeared in the apparently comprehensive scare list of 500 Questions, and despite genuine establishment fears over the viability of keeping a nuclear arsenal after Scottish independence, British news outlets worked to keep it away from media debates. Mass extinction, that is, does not count as a risk, at least not on the level of the cost of a first class stamp.

There is an obvious senselessness to this; but as numerous commentators have noted, nuclear ‘deterrence’ remains a fundamental existential need for the UK state. For one thing, it sublimates any conflict, domestic or international, into ‘the economy’, and acts as a crucial depoliticising tool. Numerous reports of the relatively peaceful 2000s-10s acknowledged that nuclear weapons were part of the existential makeup of the UK and should be developed and upgraded ‘for at least the next 50 years’, as Tony Blair had it. In fact, even ‘old left’ Labour had long history of squashing unilateralist movements within the Party, from Harold Wilson through James Callaghan to Neil Kinnock, leaving no realistic route within the UK Parliament. Even the 2019 Labour manifesto under a Jeremy Corbyn probably put in place partly to answer the ‘Scottish problem’, simply stated that ‘Labour supports the renewal of the Trident nuclear deterrent’.

Stronger Together, Warheads and Propaganda War

In the 2010s the UK government was at best trying to redefine British exceptionalism as ‘leadership’ of a vague conception of multilateralism in a nuclear-weapons free world belonging to an unimaginable future, usually restating nuclear desires for fuzzy reasons of security. But despite the very real fears at the heart of British government, the identification of the independence referendum to the only viable route to dealing with extinction-level weapons was left almost solely to independent projects like Bella Caledonia and National Collective, as well as outliers like John Ainslie.

By the end of the decade the UK was announcing its commitment to the W93 warhead, for unclear, though partly financial, reasons. Meanwhile of course nuclear-armed belligerents who fancied themselves as understanding longer civilizational shifts – Vladimir Putin, most obviously – would perceive British decline as an opportunity, leading us back to the hair-trigger brinkmanship/ accident model. This faultline in governmental and social attitudes to extinction-level weapons suggests a key to the national thinking of futurity – and yet official British sources of ‘facts’ saw the risk as lying with those who want to step away from nuclear brinkmanship. There is perhaps no more telling statement of Scottish independence’s ‘risks’.

Many of the scares of 500 Questions, then, point to a hyperbolic historical oddity from the midst of a propaganda war. But some of the threatened disasters have clearly worked backwards; any serious threats about a Yes vote in fact largely describe the outcomes of a No vote. This real historical unfolding may have something to do with the document’s virtual unfindability now. Why did the groundless spectre of risk seem to achieve so much, against examples of demonstrable social good? The key is in a nagging sense of disorientation pressed by a state whose authority is fundamentally the claim of an arithmetic high ground, a role as the ultimate evaluator of all relationships. Under the name of protection from risk, a shared public realm can be inexorably yet comfortingly ground down, inequality can balloon within an overall performative ethics of equality, mass extinction weapons can remain spoken common sense within officially-touted increases in tolerance. In this thinking the danger is not precipitous decline, poverty, or even mass extinction, all of which are familiar and avoid any political disruption; the danger is any kind of unmanaged change at any given moment. The weaponization of change as risk serves to make the future unimaginable. Home, as numerous commentators have described, then consists of a ‘hell of the same’. And for all the daftness of the 500 Questions, it formed part of an government-backed factual information flow apparently necessary for informed decision-making and settling the constitutional (il)legitimacy of self-determination on a semi-permanent basis. In light of what actually followed, would any its authors, or even Baron Darling of Roulanish, like to reaffirm this risk-a-thon as a mandate for British sovereignty?

The ‘500 Questions’ ploy sometimes called ‘the devil is in the detail’ ploy is a tactic deployed by opponents who are seeking to present themselves as ‘reasonable’ and ‘prepared to be open-minded’ and ‘consider the issues objectively’.

It is the philosophical ‘perfectionist fallacy’ which is being deployed. The perfectionist fallacy is if one thing fails then the whole thing fails.

Of course in life very few things are perfect and the Westminster system of Government is one of the most imperfect of all. And, when there are any proposals for things like PR, its ‘flaws’ are immediately highlighted – so, ‘best stick with what we know; it’s tried and tested, and despite its flaws it has worked.’ Strangely, the ‘perfectionist fallacy’ does not seem to apply to that statement.

Also, in the 500 Questions variant you have highlighted only these questions and no others are permitted to enter the debate. You use the nuclear weapons as an example of excluded questions and it is excluded because ‘deterrence has worked’. QED.

Many Westminster politicians study PPE – Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Oxford or Cambridge (you can study these subjects at other universities, but none come anywhere near the private school/wealthy landowning/financial nexus that some get admitted to at Oxford and Cambridge. And, a feature of the teaching approach is the tutor system where they learn how to debate and discuss according to the kind of rules that apply at Westminster. And part of this involves rhetoric. Now rhetoric is generally a good thing, but it can be misused as demagogues and conmen have shown over the centuries. And the misuse of rhetoric entails the wilful deployment of a wide range of philosophical fallacies, because most fallacies, if unexamined, have a hint of plausibility about them. So, the PPE course at Oxford and Cambridge and the tutor system within their small ‘elite’ colleges’ are training schemes for mendacity and fraud.

The City of London is a money laundering Ponzi Scheme. It is another example of a system, which if transparent and trusting and mutually beneficial rather than profit maximising, can bring benefit to millions of people.

@Alasdair Macdonald, I don’t remember 500 Questions, but it seems reminiscent of the cacophonist approach attempted by the odd Unionist. You are quite right about the double (or multiple) standards required to avoid self-incrimination.

Ben Goldacre of Bad Science used to lament the lack of science, technology, engineering, medical etc backgrounds amongst the British decision-making class, who act as if any issue can be fudged, blustered over, distracted from, and son. Of course, nuclear deterrence has not worked; we’re only here by the skin of our teeth because of luck and occasional human sanity (a couple of Soviet officers stand out), although the overriding milieu has been extreme insanity, as Chatham House’s Too Close for Comfort (2014) report details in incident after incident after incident (and these are only the ones then in the public domain).

https://www.chathamhouse.org/2014/04/too-close-comfort-cases-near-nuclear-use-and-options-policy

The disgraceful refusal to add state terrorism to international legal definitions of terror arises from the policies of the five permanent members of the United Nations ‘Security’ Council, UK included, whose nuclear weapons are so clearly terrorist in nature that the nuclear standoff in the Cold War was openly called ‘The Balance of Terror’. And of course, the Cold War was never cold, and each hot proxy war then and since threatens escalation.

The failure to answer the basic questions regarding what currency an independent Scotland would use and what/where would it’s central bank be are not minor issues and certainly would sway a significant number of voters. If the answer, for example, is the Scottish pound and a central bank in Edinburgh then would the new currency be pegged to sterling or the Euro and if so, what are the implications for fiscal sovereignty?

What will your gas bill be in 6 months? Who will be prime minister? Will you have a job? Will we be at war? Will you have still have your human rights in 2 years? The right to protest? What will inflation do to your salary in a year’s time? How much will a week’s groceries cost? Can your female family members trust the police? Will there be power cuts next winter? Will you be able to get a hip operation if you need it? Cancer treatment? An ambulance? A GP appointment? Will teachers be on strike next year? Will your local primary school still be open? Your library? Sports centre?

What? You can’t answer these simple questions? And you expect me to support the union?

Life is uncertain. Politicians can’t offer certainty.

I worry that when we get another vote on independace project fear might win out again, the better together crew control nearly all the media including the BBC, a huge advantage for them.

This is the running total on MSN so far.

SCOTTISH INDEPENDENCE BIAS WATCH

Independence related articles on MSN since referendum date announced

Anti-Neutral-Pro = 254-9-7

It’s a credit to the Scottish people that independence still hovers around 50% given the scale of the bias. It will only get worse as any vote approaches.

On the risks of British militarism, I watched BBC Northern Ireland’s documentary Hooded Men — Britain’s Torture Playbook, and not only was I struck (once again) by how truly evil, brazenly sociopathic and dismally unaccountable the British Establishment are, but how in this particular story its worst offenders (of rank) get promotion after promotion, including the royal appointments at the top of tree (of Terror).

https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m001hlj7/hooded-men-britains-torture-playbook

The programme makers rightly note that the British exceptionalism which allowed the empire to squirm out of its responsibilty for torturing its Irish subjects was enthusiastically copied by other empires like the USA (they have it writing).

What are the risks of living in a violently psychopathic Empire with a cult of militaristic royalism and a world-beating secrecy regime whose official orifices loudly proclaim their intentions of removing human rights while issuing their uniformed thugs and plainclothes assassins with legal immunity for crimes against the person?

I wonder if the question ‘should male rapists be allowed to stay in female jails’ be included in the next referendum debate?

The GRA is pretty much what Theresa May & the Tories intended introducing plus a few minor tweaks. When Johnson took over he recognised the unpopularity of it among his fascist and elderly voters and binned it. The Tories, along with their gutter press allies, have weaponised it and are using it for anti-independence propaganda, portraying themselves as the saviours of Scotland while their loyalist lapdogs lap it up. The sight of Jack’s Jackboots outside Holyrood with their union jacks, ‘Sturgeon Out’ chants and their coincidental, simplistic gender comment posters says it all.

The Scottish govt should be getting praise for setting a good example for the English on the subject of trans sexual offenders in women’s prisons. It won’t though as the gutter Tory press are having a field day with suckering the dim.

From a Guardian article in 2021

‘High court for England and Wales – Lawful to imprison trans women sexual offenders in female jails, judge rules’.

“The court heard that in 2019 there were 163 trans prisoners in England and Wales, 81 of whom had been convicted of one or more sexual offences. Of the 163, 34 were held in women’s prisons.

Between 2016 and 2019, a total of 97 sexual assaults were recorded in women’s prisons, of which seven appeared to be committed by trans prisoners without a GRC. It is not known whether any were committed by trans women with a GRC but the number of trans prisoners with a GRC across all jails is thought to be in single figures.”

Was there a similar outcry in 2021? If there was I can’t remember it.

So your perfectly relaxed about male rapists been put in womens prisons and if you disagree your a ‘fascist’ in thrall to the gutter press?

No, I’m perfectly relaxed that “Scottish Government bans trans prisoners with history of violence against women from moving to female jails” and the good example it sets our colonial masters who are clearly experiencing a lot of problems going by that Guardian article.

I’m also questioning why this is being portrayed as a Scottish problem.