Irish Pages, Literary Ambitions

The Irish Pages Press ‘publishing outstanding books in English, Irish and Scots’ goes from strength to strength. As well as celebrating this revival (and concentrating on a few of its recent publications) we should look at how to strengthen these connections and ask why they aren’t more possible here?

The Irish Pages Press/Cló An Mhíl Bhuí has emerged to become the all-Ireland literary journal and press, now with permanent Editors in Scotland, Wales and England while remaining rooted in Belfast and Ireland. If we can celebrate the breadth of ambition of such as Irish Pages – we can also contrast that with the sorry state of affairs here in Scotland (“Scotland has only two full time arts correspondents & one arts magazine programme”).

Irish friends might warn against over-simplification, and it is true that The Irish Pages Press/Cló An Mhíl Bhuí is a relative newcomer (launching in 2003 as a journal and as a press in 2018) but it has a vim and confidence that has no Scottish equivalent. It is considered by many the Irish equivalent of Granta in England or the Paris Review in the Unites States. If we wonder about the connective tissue that unites writing, theatre, acting, film and storytelling in Ireland, and lets such talent flourish onto the big screen, we can also reflect on the state of Scottish arts and the lack of such output.

Patchy and Negligible

Since the Scottish Review of Books had its Creative Scotland funding pulled in 2019 (as Claire Squires covered in Bella here (‘Patchy and Negligible‘), little has emerged to replace it. The SRB website still states, in a forlorn homepage graphic: ‘Archive reviews are available on this site while we work out our way forward‘).

‘Work our way forward’ is a great line – and it would be wrong to portray Scotland as a blasted heath. The Glasgow Review of Books, with its commitment to “marginal, peripheral or neglected writers and their work” and being ‘non partisan’ by which they mean wanting “to represent writers from all communities. In particular, this means giving a platform to working-class voices, and those from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds” gives heft to its considerable output. Northwords Now (‘new writing, fresh from Scotland and the wider North’) is also a focal point for writing from the Highlands and Islands publishing two issues per year, plus its annual Gaelic supplement – ‘Tuath’. We also have the free ezine The Bottle Imp and the Scottish Literary Review, and Scottish Language (‘the best, latest research on Scotland’s languages and linguistics’) …

… we also have Heather Parry’s Extra Teeth (‘words with bite’) and Product (music+film+books+art x ideas’) magazines as well as Dark Horse (edited by Gerry Cambridge) and the excellent Drouth (‘Scotland’s weekly web journal for literature, art, politics and informed critical commentary’, as well as Gutter (‘the magazine for new Scottish and international writing’).

There is much more, and more activity on online platforms (such as the brilliant Scots Whay Hae! or You Call That Radio?), live events and in micro-publishing and podcasts than traditional print formats. But nothing feels as substantial, grounded and ambitious as Irish Pages. The difference maybe with other journals and publishing houses is that IP brings something to the Scottish literary/writing landscape that maybe we can build on?

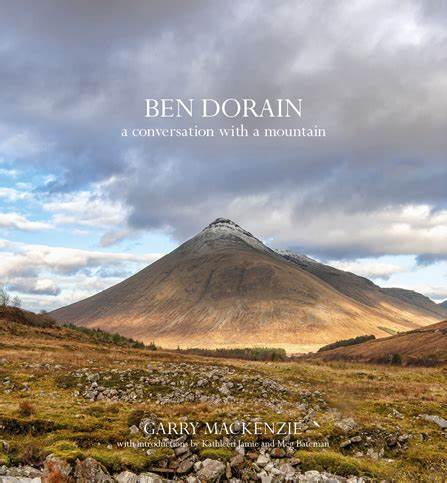

As well as translations such as Slavenka Drakulić’s Invisible Women and Other Stories, Irish Pages has forthcoming titles with a Scottish connection such as Ben Dorain: a conversation with a mountain by Garry Mackenzie and Brian Holton : Aa Cled Wi Clouds She Cam – The Irish Pages Press by Brian Holton.

As Irish Pages explains: “Brian Holton is unique in that he can translate directly into Scots from the Chinese. This anthology consists of translations into Scots and English of the first sixty poems of the standard anthology Song Ci Sanbaishou (“300 Sòng Dynasty Song Lyrics”), edited by Zhu Zumou (1924), with a Translator’s Afterword/Owresetter’s Eftirword.”

As the Makar Kathleen Jamie writes in the introduction to Ben Dorain: a conversation with a mountain …

“When we may feel as though our species and our planet is cascading into a future unknown, and uncertainty is all about, it may seem odd to publish a book which is ‘a conversation’ with a mountain, the very symbol of solidity. The mountain is Ben Dorain, which rises near Bridge of Orchy. It appears as Fuji-esque cone from some angles. The conversation is also with a praise poem composed 250 years ago, by Duncan Bàn MacIntyre. MacIntyre’s poem is a musical paean to this one particular Scottish mountain and its deer. The original poem is in Gaelic, a language no longer spoken on that mountainside.

But what Gary MacKenzie has done, in this wonderful book, is to revivify that poem. He has created a new ‘inhabited music’ which springs McIntyre’s work into the present day. It’s not a translation, nor a modernised version, though there is that also. He has opened MacIntyre’s mountain poem like a geode, to use a geological term, and he has created an environmentally-aware, science-informed poetic counterpoint in English, which he presents dancing along with MacIntyre’s re-expressed eighteenth-century vision. Like the deer they so admire, the two poets’ lines leap back and forth across the page, across times, across languages, across species and poetic forms. It is a new work which alerts us to the tradition, which is to say, to the consciousness of the past. It calls this consciousness into the present, so that its wisdom might strengthen us for the environmental challenges to come.

But this is not primarily a political work. This is a work of love: of landscape and animals and poetry. Despite the shifting grounds which surround it, Ben Dorain the mountain remains true and centred, its marvellous creatures marvellously observed.”

Duncan Bàn MacIntrye’s eighteenth-century long poem in Gaelic, Moladh Beinn Dobhrain (Praise of Ben Dorain), is also included and follows Garry MacKenzie’s long poem in English.

There is no need to apologise for focusing on the potential for art and literature in such dark times. Understanding, translation and communication at a deeper level seem more essential in times of war and carnage than ever before. The need for poetry and story and internationalism from the marginal and the dispossessed seems to be the calling cry for our era, and anything we can do to amplify the journals and forums that give space to those voices the better. Lets work out our way forward.

Wonderful hill, Beinn Dorain.

Scotland is very far from being ‘a blasted heath’. Beyond the ‘Scottish Literary Review’, the work of the Association for Scottish Literature is admirable. The latest in its excellent Occasional Papers series (No. 26), ‘Writing Scottishness: Literature and the Shaping of Scottish National Identities’, ranges over Scottish writing from the 16th Century Maitlands of Lethington to Irvine Welsh and Peter Arnott, and includes insightful commentary on Scottish writers from a number of French scholars. Scotland certainly has the talent and international contacts to produce something comparable in quality to ‘Irish Pages’. All that is needed is the will.

Yeah, I didn’t say it was a ‘blasted heath’. I agree absolutely that Scotland has the talent and contacts to produce something comparable to ‘Irish Pages’ – what we need is ambition and funding …